unwarranted assumption

advertisement

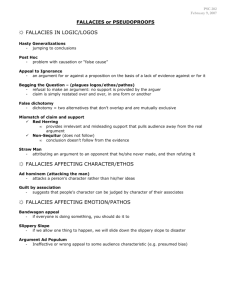

Philosophy 200 unwarranted assumption Begging the Question • This is a form of circular reasoning. Questionbegging premises are distinct from their conclusions, but cannot be believed without believing the conclusion. Begging the Question Capital Punishment is murder Murder is wrong Capital Punishment is wrong. Begging the Question Capital Punishment is murder Murder is wrong Capital Punishment is wrong. This premise “begs the question” because nobody who did not already agree with the conclusion would agree to that premise. Begging the Question • Question-begging premises make an argument useless, even if still valid (or even sound) because the whole point of an argument is to support a conclusion with things that are more acceptable. Complex (loaded) Question • Classic example: “Have you stopped beating your wife?” – Any answer implies wife-beating has taken place. Complex (loaded) Question • Classic example: “Have you stopped beating your wife?” • The best way to respond to one of these is to point out that it’s loaded and disagree with the assumption of the question. Accident • Most generalizations have specific exceptions built in. Accident • Most generalizations have specific exceptions built in. • Consider: – Traffic laws Accident • Most generalizations have specific exceptions built in. • Consider: – Traffic laws – Rules like “No punching” Accident • Most generalizations have specific exceptions built in. • Consider: – Traffic laws – Rules like “No punching” – Killing people is always immoral Accident • The fallacy of accident treats the acknowledged exception as a disproof of the general rule or else applies the generalization to the acknowledged exception as if it still applied. Hasty/Biased Generalization • These we covered when talking about generalizations • Generalizing from too few cases or nonrepresentative cases are two ways of making poor generalizations. False Dichotomy/Dilemma • Is when only two options are provided that are not actually the only options. False Dichotomy/Dilemma • Is when only two options are provided that are not actually the only options. – Pompey: “If you’re not for me, you’re against me” – Caesar: “If you’re not against me, you’re for me” False Dichotomy/Dilemma • Is when only two options are provided that are not actually the only options. – “Either we continue to ban homosexuals from the military or else we’ll have to let absolutely everyone in.” Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. • Once one thing is correlated with another, there are four logical possibilities: Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. • Once one thing is correlated with another, there are four logical possibilities: – A is the cause of B Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. • Once one thing is correlated with another, there are four logical possibilities: – A is the cause of B – B is the cause of A Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. • Once one thing is correlated with another, there are four logical possibilities: – A is the cause of B – B is the cause of A – Some third things causes both Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. • Once one thing is correlated with another, there are four logical possibilities: – – – – A is the cause of B B is the cause of A Some third things causes both The correlation is simply coincidence Causal Fallacies • Remember, correlation IS NOT causation, it merely indicates evidence of a possible causal relationship. • Once we determine the explanation for the correlation, that explanation is the causal factor. • Once one thing is correlated with another, there are four logical possibilities: – – – – A is the cause of B B is the cause of A Some third things causes both The correlation is simply coincidence Slippery Slopes • For whatever reason, many will argue that some action is a slippery slope to another action without realizing that such reasoning is fallacious. • We will examine three kinds of slippery slope “arguments”. Conceptual Slippery Slope • Ordinarily, this is perfectly acceptable reasoning, but when it argues similarity by transitivity, it has become a slippery slope argument, and a fallacy. A series of insignificant differences can add up to a significant difference. Conceptual Slippery Slope • This argument relies on the vagueness inherent in language to argue that no distinction should be made between two things because they are not all that different. • Ordinarily, this is perfectly acceptable reasoning, but when it argues similarity by transitivity, it has become a slippery slope argument, and a fallacy. A series of insignificant differences can add up to a significant difference. Fairness Slippery Slopes • Otherwise known as a line-drawing fallacy. Fairness Slippery Slopes • Otherwise known as a line-drawing fallacy. • Where to draw a line can be a legitimately argued point, but where the argument form turns fallacious is when one argues because there is controversy on where to draw a line, no line must be drawn. Causal Slippery Slopes • These are the most common variety. • These are often called ‘snowball’ or ‘domino’ arguments. Causal Slippery Slopes • These are the most common variety. • These are often called ‘snowball’ or ‘domino’ arguments. • When a clear and likely means of causation is described in each step of such an argument, it isn’t known as a slippery slope argument, but instead a chain argument (which is valid). Causal Slippery Slopes • These are the most common variety. • These are often called ‘snowball’ or ‘domino’ arguments. • When a clear and likely means of causation is described in each step of such an argument, it isn’t known as a slippery slope argument, but instead a chain argument (which is valid). • When causality is badly misunderstood, the argument becomes a fallacy. Example: militarism • Consider: “If we invade Iraq, after having invaded Afghanistan, then it will only be a matter of time before we invade Iran, then the rest of the middle east, and then the US will be locked into a holy war with the entire Islamic world.” Example: militarism • Consider: “If we invade Iraq, after having invaded Afghanistan, then it will only be a matter of time before we invade Iran, then the rest of the middle east, and then the US will be locked into a holy war with the entire Islamic world.” • This argument is fallacious in that it badly misrepresents causality. It relies on previous decisions causing future ones, which is generally not the case, and also consider why the actual argument didn’t in fact happen, in spite of the antecedent conditions occuring.