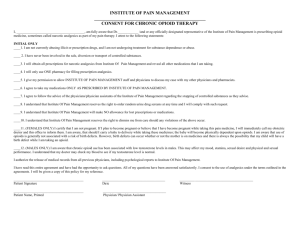

Using non-opioid pain medication first (FSMB model policies)

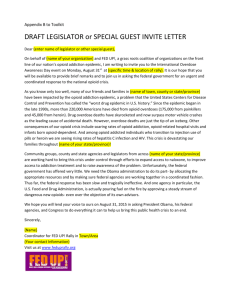

advertisement