Logical behaviourism

advertisement

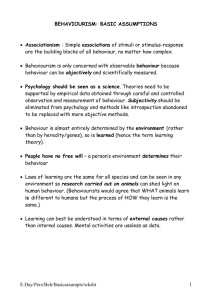

Logical behaviourism Michael Lacewing enquiries@alevelphilosophy.co.uk Methodological behaviourism • A theory about how a scientific psychology works (Watson, Skinner) – To be properly scientific, psychology must deal with what can be observed, not what cannot – Therefore, psychology should aim only at the explanation and prediction of behaviour without appealing to ‘inner’ mental states Logical behaviourism • A philosophical theory about what mental states are – Talk about the mind and mental states is talk about behaviour • Rejecting dualism’s ‘ghost in the machine’ (Ryle) – Our psychological terms are about what people do, and how they react – This is a claim about what mental states are, not just about how we know about them The basics • Behaviourism is a materialist theory: – There is no mental substance – Mental states are analyzed in terms of behaviour, which depends upon physical properties • Simplest from: to be in mental state x is to behave in way y – E.g. To be in pain is to exhibit painbehaviour Objections • Suppressed pain: Pain without pain behaviour • Same mental state can be expressed by different behaviour on different occasions • Many mental states, e.g. knowing French, are dispositions, not occurrences The analysis • Mental states are dispositions of a person to behave in certain ways (in certain circumstances) – To be in pain is to be disposed to cry out, nurse the injured part of the body … • Analytic behaviourism – Concepts that refer to mental states can be completely translated (or reduced) into concepts that refer only to behaviour Ryle against dualism • Ryle understands substance dualism (‘the official doctrine’) as claiming: – the mind can exist without the body; – the body is in space and is subject to mechanical (physical) laws, while the mind isn’t; – in consciousness and introspection, we are directly aware of our mental states and operations in such a way that we cannot make mistakes; and – we have no direct access to other minds, but can only infer their existence. Ryle against dualism • If this were right, our mental concepts would refer to secret episodes in our minds – We can’t know whether a mental description of someone is true unless they introspect and tell us – This makes using these concepts impossible The meaning of psychological terms • Psychological terms must be grounded on what is publicly available – Children can only learn to name and report their mental states through interaction with others – Other people must therefore be able to identify the expression of mental states in our behaviour The category mistake • Category mistake: To treat a concept as belonging to a different logical category from the one it actually belongs to – E.g. Oxford university; team spirit • The mind is not another ‘thing’ – Mental concepts (of ‘states’ and ‘processes’) do not operate like physical concepts • The ‘para-mechanical hypothesis’: – since physical processes can be explained in mechanical terms, mental concepts must refer to non-spatial, non-mechanical processes Dispositions • How something will or is likely to behave under certain circumstances – E.g. solubility, being hard • Mental concepts, e.g. being proud, pick out a set of dispositions that are ‘indefinitely heterogenous’ – But statements using mental concepts can’t be reduced to hypothetical statements about behaviour Thinking • How can an internal process like thinking quietly be a disposition to behaviour? • Reply: thinking is internalized speaking – Speaking is behaviour, and thinking is acquired later – The silence is inessential to the nature of thinking – you can think out loud or with pen and paper • Thinking isn’t just a disposition, but also an occurrence – Cp. ‘it is dissolving’ – It is still the basis for attributing dispositions