dee.ch5.23mar13

advertisement

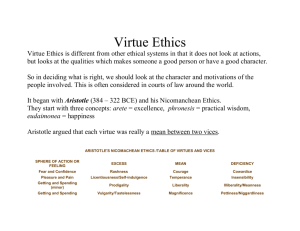

Character: Ecological Virtues How does a concern for character differ from doing our duty? In this chapter we shift our attention from taking the right action to being a good person. These two ways of reasoning are related, as we expect good persons to do what is right. A focus on character, however, requires considering an individual’s motivation and goals and recognizing that conduct is shaped by acts that are neither right nor wrong. It also means appreciating personal qualities that are intrinsically good.1 Most moral philosophers do not make a character argument in support of environmental ethics, but instead assert duties and rights or rely on consequential predictions. Their emphasis is on action. Yet reflecting on the value of character directs our attention to the teleological goal of being a good person, which is thought by many to be the basis for right action. We begin with the natural law tradition of Europe and the Tao tradition of East Asia.2 Then we reflect on the stories of Cinderella and Johnny Appleseed to see what folktales might tell us about being good. We also Character consider Christian teaching that urges us to be Teleological Being stewards of the earth. Finally, we reflect on the virtues Ethics Good of integrity, gratitude, and frugality, and assess philosophical arguments for appreciating nature. Being Good In the play Antigone by Sophocles (495–406 BCE) a young woman defies the king’s edict by burying the body of her brother, who was slain as a rebel. Antigone justifies disobeying the law of the land by proclaiming her allegiance to an eternal law, which she claims has greater authority than the decisions of any human ruler. She is punished for her act of love and faith by being put to death. In ancient Greece the death of Socrates was also tragic, as Plato (424–348 BCE) tells us in the Apology. Plato’s accounts of Socrates have to do with living a good life. We learn in these dialogues that “the unexamined life is not worth living”3 and that we should remain true to our understanding of what it means to be good. Socrates accepts the judgment of the Athenian senate, which accused him of corrupting young people, although he believes he has done no wrong. He drinks the cup of hemlock that causes his death as a way of affirming that a good citizen should abide by the rule of law.4 Stories of Antigone and Socrates reflect ethical reasoning that would later be known as the natural law tradition. Both individuals gave their lives for a higher ethical standard, which each expressed in opposition to the laws of the state. Each affirmed that being a good person means striving to know what is good and having the strength of character to live by this truth, no matter the consequences. The Natural Law Tradition The ancient Greeks found a purpose in life that seemed to give order to and also transcend the ways of nature. Sophocles gave voice to this belief in Antigone, and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) found purpose in his observations of the world around him. Plato looked for the source of what is good in eternal forms, but Aristotle relied on observations of the natural world, which is why his philosophy is an early form of science. The phrase “natural law,” however, does not refer to what modern science means by the laws of nature, but instead reflects the view that there is purpose in the natural order. Observing both animal and human life led Aristotle to conclude that humans are “happiness-seeking” animals. He argued that the pursuit of happiness must be the purpose of human life and, in this sense, was 1 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). good in itself. Aristotle also observed that human beings uniquely have the capacity to know what is good or better and to make choices. Our capacity to reason and freedom to choose are crucial for living in ways that we find fulfilling. According to Aristotle, there is a reason for everything, and every living organism has a good of its own. We discover our human nature and what it means to be good persons—and thus our purpose and goal in life— by seeing how to live together rationally in the natural world as it is. Because we are social beings, Aristotle reasoned, pursuing our natural inclination to be happy requires cooperating to realize the common good. Aristotle used the Greek word eudaimonia, which is usually translated as “flourishing,” to express this notion of individual and social happiness.5 Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) reaffirmed Aristotle’s argument that being good persons involves understanding human nature through reason. Aquinas agreed that happiness is a social as well as an individual goal and thus requires efforts to develop civic as well as personal virtues. Aquinas embraced Aristotle’s reasoning, but rejected Aristotle’s belief that understanding the order of the natural world does not require any consideration of divine will. We see this difference reflected in what each man said about virtue. Aristotle concluded that virtue requires practical wisdom, so he proposed that moderation was the virtue of all virtues, “the golden mean.” Aristotle argued, for instance, that too much courage is foolhardy, and that too much pride is vanity. Following nature, he reasoned, means always acting with moderation. In contrast, Aquinas argued that divine law was revealed in natural law. He believed that moderation was less important for being a good and happy person than the spiritual and moral virtues of faith, hope, and charity proclaimed in Christian scripture.6 Both Aristotle and Aquinas affirmed that good habits strengthen the virtues necessary for humans to flourish. Natural law reasoning holds that we will flourish, individually and as a people, if we support the character traits of being a good person—by encouraging and rewarding those who exemplify these virtues. To “do good” we need to “be good.” Jacques Maritain, a recent interpreter of Aquinas, suggests that our knowledge of the natural law is never complete and evolves throughout history. As our human conscience develops, our insight into what is “natural” will change. Therefore, he argues, “natural law” is not a set of absolute principles, but a growing awareness of our divine purpose. This formulation of natural law reasoning helps to explain mistaken judgments in the past and reminds us that our present knowledge may also need revision, as we learn from our experience. This tradition of thought is reflected in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” written in 1963 by Martin Luther King, Jr., to explain why civil rights activists were resisting segregation laws. “How does one determine when a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of Saint Thomas Aquinas, an unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in the eternal and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.”7 A Comparison with Kantian Reasoning Martin Luther King, Jr., was a Baptist preacher, but in contemporary ethical debate the Catholic Church is the primary advocate of natural law reasoning. Catholic moral teaching identifies what our purpose is, as the only creatures on earth with the capacity to be moral. Contrasting Catholic natural law reasoning with the moral philosophy of Kant is helpful in clarifying each. Kant emphasizes that reason defines the ethical character of each individual, whereas the natural law tradition conceives of reason as embedded in the natural order. For Kant, reason requires that we respect the autonomy of the individual. For Catholic moral teaching, reason enables those trained in spiritual and 2 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). ethical discernment to guide the rest of us in our choices. The Catholic hierarchy explains our purpose rather than trusting us to use our reason (our autonomy) to figure this out for ourselves. (Some Catholic teachers, however, argue that we may each trust our conscience once our reason is well informed by the teachings of the Church.) Whereas Kant proposes various levels of duty to deal with conflicts of duty, natural law reasoning relies on the “principle of double effect.” We must not only intend the good, but the good consequences of acting on a good intention must be at least equivalent to any bad consequences. Moreover, even if these good consequences outweigh any bad consequences, an action is not moral if its good consequences are a result of its bad consequences. Like Kant’s reasoning, consequences do not trump a good intention. Unlike Kant’s reasoning, a good intention is not sufficient to justify an action; not only must consequences be weighed, but their causal relationship must also be analyzed. The ethical debate over population control, which many believe is crucial for resolving our environmental crisis, illustrates the clear difference between these two ways of reasoning. Kantian reasoning would argue for the autonomy of a couple to decide the number of children they think they can reasonably love and support. From a Kantian perspective, all parents have this responsibility, and doing their duty should reflect their good will and not a calculation of consequences. Would Kant oppose the availability of birth control, or government programs encouraging the use of birth control to limit population growth? I doubt it, as long as the decision was left to the conscience of parents. He would consider well-informed parents more able to act rationally and do their duty. In contrast, Catholic moral teaching argues that our human purpose involves marriage between a man and a woman and then having children if this is possible. All forms of contraception8 are contrary to this natural purpose, and thus the Church opposes their availability and education concerning their use to prevent conception. Those using any artificial means of birth control may intend a good consequence (for example, a smaller family in order to have adequate resources for each child), but this consequence would be the result of a bad consequence (preventing the possible conception of a child). Therefore, according to the principle of double effect, the use of contraception even with a good intention is wrong. Arguing that public policy should encourage the use of contraceptives to lower population growth, because larger families will strain environmental resources, does not affect this reasoning. Good consequences for the environment may be intended, but these will be the result of acting on an intention to prevent the natural creation of life that is central to our human purpose as revealed by God in Christian scripture. In our time, many people do not believe there is a divine dimension that transcends the natural world and yet may be discerned in it. Therefore, they may not believe there is any purpose for human life. Yet more than half the people on the planet express such a faith within varied religious traditions and so utilize some form of natural law reasoning to draw ethical inferences about living together on the earth. The Tao Tradition In ancient Chinese literature, which has shaped East Asian cultures, being a good person means conforming to the way of Tao, which is understood as the order of nature or the natural order of society (or even the divine will). Although Taoist and Confucian perceptions of Tao differ, each school of thought follows this same pattern. Legend has it that Lao Tzu wrote the Tao Te Ching around 500 BCE, as he was leaving China to die in the wilderness. The Tao Te Ching says, “The greatest Virtue is to follow Tao and Tao alone.”9 In this classical text virtue is not perceived to be a character trait that a person can achieve through diligence, but instead is the delight that comes with finding and following the Tao. This is why a “man of highest virtue will not display it as his own.”10 Those who show off their “virtue” are merely pretentious. Virtue is not an accomplishment, but a way of being. 3 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). Confucius agrees in the Analects that living according to Tao is how one may encourage virtue in others. For Confucius, the virtuous person does his duty and is unconcerned about rewards. Such a person respects those with greater power, is gracious to dependents, is just with subordinates, and always acts with humility. Can such virtue be learned? Both the Tao Te Ching and the Analects agree it can, and Confucius also thought virtue could be taught. He spent his life traveling and teaching how to live a virtuous life so that the entire society would be uplifted by the good example of others. In the Analects of Confucius (551–479 BCE) Tao is understood as the ideal way of human existence and thus the best way of governing a people. This means that those who strive for a position of power in order to create the good society are foolish. “Do not worry about holding high position,” Confucius taught. “Worry rather about playing your proper role.”11 Virtue requires “balance,” he reasoned. “When substance overbalances refinement, crudeness results. When refinement overbalances substance, there is superficiality. When refinement and substance are balanced, one has Great Man.”12 This differs from Aristotle’s virtue of moderation, for Confucius is not talking about avoiding extremes, but about balancing what is done and the way it is done. In this respect the Tao Te Ching and the Analects diverge in their understanding of how to follow Tao. To promote the virtue of refinement Confucius teaches the importance of ceremonies, music, and public rituals, whereas the Tao Te Ching evokes images from nature to suggest what living a virtuous life involves. As “water overcomes the stone,” a person of virtue “is like water, which benefits all things,” but “does not contend with them.”13 The two schools of the Tao tradition agree, however, that refraining from action, rather than trying to make the world right, is often the way to harmony, which is the goal of good living. The Tao Te Ching teaches: The Way takes no action, but leaves nothing undone. When you accept this The world will flourish, In harmony with nature.14 “Nature is not kind,” the Tao Te Ching reminds us, but “treats all things impartially.” So virtue also involves treating all people impartially, rather than having mercy on some and not on others.15 Taoists and Confucians agree that from “mercy comes courage,” as the Tao Te Ching affirms, and from “humility comes leadership.”16 Moral Presumptions The natural law tradition asserts that we should resist human law that conflicts with higher law, which Aristotle discerned in the rational order and purpose of the natural world. Aquinas agreed, but reasoned that a higher law is revealed in Christian scripture. Both thought that to be happy in a flourishing society people must be reasonable and virtuous. Aristotle praised the virtue of moderation and criticized humility as having too little self-regard. Aquinas endorsed humility and the virtues of faith, hope, and charity as crucial for a good and happy life. In the Tao tradition human flourishing is understood as harmony rather than as happiness. The Tao Te Ching recommends the virtues of mercy and humility, but does not distinguish religious faith from cultural traditions. It invites us to learn from nature by pointing out that the flow of water wears away stone and in doing so both shapes the landscape and nurtures life. This notion of Tao is also reflected in the teaching of Confucius that we should respond to unjust leaders by being civil and virtuous, which will shame them and in this way prompt them to become civil and virtuous. 4 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). This seems analogous to Plato’s view of Socrates, but differs with the ideal of resisting unjust authority exemplified by Antigone. Neither the natural law tradition nor the Tao tradition directly addresses the question of how humans should care for nature, which is the concern of environmental ethics. Taoist teaching, however, encourages drawing inferences from nature about being more in tune with it. (Today we might say living more ecologically.) The natural law and Tao traditions agree that we should learn from the natural order, but they differ in the inferences they draw. Children’s Stories Stories in every culture illustrate what it means to be a good person, but the role of nature in these stories varies. The following children’s stories suggest in different ways how we may live in harmony with nature. Cinderella This popular children’s story is about a girl who endures mean treatment at the hands of her stepmother and stepsisters without becoming a mean person, and who eventually finds love and a new life. A Greek version of Cinderella published in the first century BCE may be the earliest written example of the story, but it was also popular in a Chinese version after the ninth century CE.17 This is evidence that Cinderella is not simply a Western tale, and may reflect character traits and a hope for a better life that have also been important in East Asian cultures. The contemporary American story follows a French version edited by Charles Perrault in the seventeenth century. In this version Cinderella is described as “of unparalleled goodness and sweetness of temper,” and the transforming miracle of the story is performed by Cinderella’s fairy godmother.18 In all versions, Cinderella is rewarded for her goodness. In the Grimm brothers’ tales she is aided by a tree and a bird, and in the Chinese version she is helped by the bones of a fish she fed and loved, before it was killed by her stepmother to feed the family. The story of Cinderella does not tell us how to care for the earth, but it does offer hope in facing what appears to be a hopeless situation—and a sense of hope will be important as we confront the environmental crisis. Johnny Appleseed The legend of Johnny Appleseed is based on the life of John Chapman, who traveled barefoot, wearing only rags, through the states of Ohio and Indiana in the first half of the nineteenth century. Johnny Appleseed, as Chapman was known by 1806, transported apple seeds to the frontier and planted nurseries for settlers who would come later.19 An Ohio newspaper relates this story about Johnny: “One cool autumnal night, while lying by his camp-fire in the woods, he observed that the mosquitoes flew in the blaze and were burnt. Johnny, who wore on his head a tin utensil which answered both as a cap and a mush pot, filled it with water and quenched the fire, and afterwards remarked, ‘God forbid that I should build a fire for my comfort, which should be the means of destroying any of His creatures’.”20 Johnny’s story may inspire some to live in nature with greater simplicity and gratitude—virtues that seem to contribute to a more ecological way of being a good person. Yet he is not a model for those who believe environmental ethics should emphasize the value of all life (an ecocentric or biocentric perspective). Johnny Appleseed was seeking only his own salvation,21 and by planting apple trees he made it easier for settlers who followed him to transform the wilderness. Christian Stewardship 5 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). Many well-known stories about being good come from the New Testament. Often these stories do not concern God directly, but illustrate what it means to be a loving person. This is true of the story of the Good Samaritan, which tells of a man helping an injured stranger.22 This is not a story about doing our duty, because according to the ethical teachings of his time, the Samaritan does not have a duty to help a stranger in need. Instead, the story urges us to go beyond our duty by being good neighbors. This may even mean caring for an enemy, which is part of the moral of the parable of the Good Samaritan. The injured man in the story is a Jew, and in the first century CE Jews and Samaritans had known five centuries of conflict. A contemporary version of this New Testament story might have a Palestinian helping an injured Jew on the road to Jericho, and if we were to tell the parable in this way, everyone listening would see its radical implications. The stories and parables related in the New Testament are about following Jesus by loving God and our neighbors, but concern being good persons rather than loving or respecting nature. To use these religious teachings to promote a more ecological way of life, Christians must argue that keeping the Great Commandment—to be persons who love God and their neighbors—implies a more caring attitude toward the natural world.23 Catholic Ethics Catholic social teaching has transformed the New Testament commandment to be loving persons into a call to reclaim “our vocation as God’s stewards of all Creation.”24 For example, a statement by the bishops of New Mexico urges Catholics to consider how they might change their lives in order to end “the destruction of our planetary home and contribute to its fruitfulness and to its restoration”:25 • • • • We invite our parents to teach their children how to love and respect the earth, to take delight in nature, and to build values that look at long-range consequences so that their children will build a better place for their own children. We invite our worshiping communities to incorporate in their prayers and themes our [the church’s] confessions of exploitation and our rededication to be good stewards, and to organize occasional celebrations of creation on appropriate feast days. We invite our parish leaders to become better informed about environmental ethics so that religious education and parish policies will contain opportunities for teaching these values. We invite our public policy makers and public officials to focus directly on environmental issues and to seek the common good, which includes the good of our planetary home. The bishops conclude by calling on government officials to eradicate actions and policies that perpetuate environmental racism and to work for an economy that focuses on equitable sustainability rather than on uncontrolled consumption of natural resources and acquisition of things. The bishops base this call to action on three passages from Christian scripture. First, they cite the story of creation in Genesis 1–2: “The moral challenge begins with recalling the vocation we were given as human beings . . . [when] God created humankind to ‘have dominion’ over all creation.”26 The statement argues that in Genesis the word dominion does not mean unrestrained exploitation: “[R]ather it is a term describing a ‘representative’ and how that person is to behave on behalf of the one who sends the representative. We are God’s representatives. Therefore we are to treat nature as the Creator would, not for our own selfish consumption but for the good of all creation.”27 The emphasis in this teaching is on who we are, as persons created in “the image and likeness of God” (Gen. 2:15). “This part of the story suggests that we are brought into being to continue the creative work of God, enhancing this place we call home. In addition to representing God’s creative love for the earth, humankind is also responsible for ensuring that nature continues to thrive as God intended.”28 6 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). To illustrate what seeing “the universe as God’s dwelling” might mean, the statement evokes the story of Saint Francis of Assisi and quotes his well-known prayer: “Praise be my Lord for our mother the Earth, which sustains us and keeps us, and yields diverse fruits, and flowers of many colors, and grass.”29 A second reference to scripture identifies the parables of Jesus, which clearly indicate that we will have to give an accounting of how we have managed our stewardship responsibility as the caretakers of the earth and its resources. Loving our neighbors by using our resources charitably is part of this responsibility. The third reference to scripture comes at the end of the pastoral statement and concerns renewing the earth. It points to the biblical promise “of the New Heaven and the New Earth” that “we as faithful stewards either enhance or contradict with our behavior and lifestyle.”30 This now means reducing our consumption. “[I]f there is to be a future, if we are truly partners in shaping the promise of the New Jerusalem, the new ‘City of Peace’ we can do no other. God gives us the courage to pray: ‘Send forth thy Spirit, Lord and renew the face of the earth’.”31 There are other pastoral letters as well as statements from the US Catholic Conference of Bishops.32 These calls to stewardship draw on the 1987 encyclical Solicitude Rei Socialis issued by Pope John Paul II, which asserts three moral considerations with respect to the environment. The first involves becoming aware that we cannot use with impunity animals, plants, and natural elements simply as we wish, for our’ own economic needs. The second requires admitting that using some natural resources as if they were inexhaustible endangers their availability for both the present generation and all generations to come. The third moral consideration acknowledges that industrialization has polluted the environment, with serious consequences for human health. In 2009 Pope Benedict XVI directly addressed the environmental crisis in his encyclical, Caritas in Veritate. He urged that we recognize in nature “the wonderful result of God’s creative activity, which we may use responsibly to satisfy our legitimate needs, material or otherwise, while respecting the intrinsic balance of creation.” Nature is the setting for our lives and “expresses a design of love and truth.” What is needed now, Benedict wrote, are “new life-styles ‘in which the quest for truth, beauty, goodness and communion with others for the sake of common growth are the factors which determine consumer choices, savings and investments.’”33 Economic incentives or deterrents are important to protect the environment, the pope affirmed, “but the decisive issue is the overall moral tenor of society. If there is a lack of respect for the right to life and to a natural death, if human conception, gestation and birth are made artificial, if human embryos are sacrificed to research, the conscience of society ends up losing the concept of human ecology and, along with it, that of environmental ecology.”34 By “human ecology” he means what traditional Catholic teaching has meant by living according to natural law. In Catholic teaching the environmental crisis has been caused by our failure to embrace our purpose in life on Earth, which is revealed in scripture and reflected in nature. Thus, in Catholic teaching environmental ethics is necessarily anthropocentric. “If the Church’s magisterium expresses grave misgivings about notions of the environment inspired by ecocentrism and biocentrism, it is because such notions eliminate the difference of identity and worth between the human person and other living things. In the name of a supposedly egalitarian vision of the ‘dignity’ of all living creatures, such notions end up abolishing the distinctiveness and superior role of human beings.”35 Protestant Teaching A survey conducted in early 2006 by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life verifies that majorities of all major American religious groups support stronger measures to protect the environment, but also shows that evangelical Protestants are less likely to support this position.36 Protestants who see themselves as liberal or progressive37 take a position on environmental ethics that, despite diverse theological arguments, 7 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). is for all practical purposes the same as Catholics’ position.38 Evangelical Protestants, however, are deeply divided. Evangelical Protestants emphasize saving souls and, until recently, most believed that a concern for the environment was a distraction from their mission, which they understand as preparing for the coming rapture and return of Jesus. “Scripture teaches that Christ . . . [is] going to make a new heaven and a new earth. So in that sense I am not so concerned with this present world because I know it is going to be replaced with a better, greater one.”39 Evangelical leader Rev. Richard Cizik acknowledges the strength of this belief among evangelical Protestants, as well as their suspicion of environmental arguments that rely on science rather than on a Christian view of nature. Nonetheless, Cizik says, “We, as evangelical Christians, have a responsibility to God, who owns this property we call earth. We don’t own it. We’re simply to be stewards of it.”40 The recent Evangelical Climate Initiative links climate change with ethical imperatives that are accepted by evangelical Protestants. “The same love for God and neighbor that compels us to preach salvation through Jesus Christ, protect the unborn, preserve the family and the sanctity of marriage, and take the whole Gospel to a hurting world, also compels us to recognize that human-induced climate change is a serious Christian issue requiring action now.”41 The statement “Climate Change: An Evangelical Call to Action” relies on science to demonstrate that the threat of human-induced climate change is real and will most heavily impact the poor of the world. However, it relies on the Bible to affirm three “Christian moral convictions” that require a faithful response to climate change: • • • [W]e love God the Creator and Jesus our Lord, through whom and for whom the creation was made. This is God’s world, and any damage that we do to God’s world is an offense against God Himself. (Gen. 1; Ps. 24; Col. 1:16) [W]e are called to love our neighbors, to do unto others as we would have them do unto us, and to protect and care for the least of these as though each was Jesus Christ himself. (Mt. 22:34–40; Mt. 7:12; Mt. 25:31–46) [W]hen God made humanity he commissioned us to exercise stewardship over the earth and its creatures. Climate change is the latest evidence of our failure to exercise proper stewardship. . . . (Gen. 1:26–28)42 Thus the statement concludes, “Love of God, love of neighbor, and the demands of stewardship are more than enough reason for evangelical Christians to respond to the climate change problem with moral passion and concrete action.”43 The bottom line for evangelical Protestants with respect to global warming seems to be the same as for Catholics; both argue that the commandment to love our neighbors means helping the poor who are particularly disadvantaged by global warming. In addition, both preach a stewardship ethic based on the story of creation in Genesis. Critics point out that Western culture has long taken literally the divine commandment in the Genesis story of creation, which gives humankind “dominion” over the earth, and that this has led to disastrous consequences for other species and the environment. “Both our present science and our present technology,” Lynn White, Jr., writes, “are so tinctured with orthodox Christian arrogance toward nature that no solution for our ecological crisis can be expected from them alone.”44 This judgment was made in 1965, so it does not reflect any consideration of the recent Catholic and Protestant teachings on environmental ethics (nor advances in science and technology that may help us to live more ecologically). Yet Christian teaching must be measured not merely by the words of church leaders, but by changes in the lives of Christians and by their support for environmentally sustainable economic policies. The environmental crisis is clearly putting Christian virtues to the test.45 8 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). Virtues: Integrity, Gratitude, and Frugality As the Western story of civilization is largely about conquering other peoples and making the environment our property, it is not surprising that courage, industry, and perseverance are prominent virtues of Western culture. Think of legendary cowboy heroes, and also of the Laura Ingalls Wilder stories about growing up in the late nineteenth century, which ran as a television serial for about a decade a century later as Little House on the Prairie.46 We have few stories that depict courage as caring for the environment, and fewer heroes who oppose those who are exploiting and degrading nature.47 There are, however, some narratives that apply the virtues of industry and perseverance to environmental concerns. Bob the Builder I first heard of Bob the Builder stories from my youngest daughter, who as a medical student told me about a party with her friends that involved dressing up in working clothes and singing songs that everyone knew from the television show. These stories are designed to show children that happiness involves developing the virtues of industry and perseverance. The show’s website includes this exuberant affirmation: “Bob the Builder knows that the fun is in getting it done! With his business partner Wendy and his original can-do crew: Scoop the digger, Muck the digger/dumper, Lofty the crane, Roley the steam roller, and Dizzy the cement mixer, Bob has been getting jobs done all over Bobsville and beyond, and no matter what the job, he always has the right tools— teamwork and a positive attitude!”48 Of course this construction involves changing the natural environment. In this sense, Bob the Builder exemplifies the American myth that nature simply provides resources for our industry and ingenuity. Until recently in this television program, there was no hint of environmental problems or of any related ethical issues. That changed in 2007, however, when Bob the Builder began a new project in Sunflower Valley. To prevent a city from being built that would pollute the valley, Bob devised “a plan that would fit into the environment.”49 Also in 2007, while watching an episode of Bob the Builder with my young grandson, I was delighted to see that the three Rs now stand for environmental virtues: “reduce, reuse, and recycle.”50 Frugality, Gratitude, and Integrity If “reduce” in the three Rs means reducing our consumption and not only our waste, perhaps frugality would be the best way today to identify this virtue. Market forecaster Faith Popcorn says being frugal is now chic. “It’s the squeeze,” she says, “the squeeze in the environment, squeeze in the economy, squeeze on the ethics.”51 A character like Johnny Appleseed exemplifies frugality, but is probably too ascetic to be our model.52 We now need examples of how families and communities can live with greater love and respect for nature. Yet if we see the story of Johnny Appleseed as exemplifying a life of gratitude, the tale may move us to change our lives. I still remember these lines of the song that Johnny sang in the movie I saw sixty years ago: The Lord is good to me, and so I thank the Lord For giving me the things I need: the sun, the rain and the apple-seed, The Lord is good to me. And every seed that grows will grow into a tree. And some day there’ll be apples there for everyone in the world to share, The Lord is good to me!53 9 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). The first verse may seem self-centered, but the second verse expresses concern for future generations. Gratitude to God for the gifts of nature evokes a reverence for creation that John Chapman lived as he traveled through the wilderness. We might be inspired by his story, and also by the example of Saint Francis, to follow in their footsteps by reducing our “ecological footprint”54 (our impact on the environment). Cinderella persevered and escaped her life of deprivation, but we do not hear that she was grateful. If we were to look for a central virtue in her life, we might say that she had integrity.55 She was not corrupted by the meanness of her stepmother and stepsisters. Despite her suffering, Cinderella persevered in being a good person. The moral of her story might be that living with integrity leads to happiness. In the tale told by the Grimm brothers, Cinderella has a special relationship with birds, which help her sort out the peas and lentils her stepmother scatters to create a task that would have taken Cinderella the evening to complete and prevented her from attending the prince’s ball.56 Might we hope, therefore, that living with integrity will foster a closer relationship with nature? Respecting and Appreciating Nature In a critical assessment of the environmental movement, two well-known activists call for a “new politics” that requires a “mood of gratitude, joy, and pride, not sadness, fear, and regret.”57 I agree. To help others face our environmental crisis, we should foster uplifting character traits. “The moral significance of preserving natural environments is not entirely an issue of rights and social utility,” Thomas E. Hill, Jr., writes, “for a person’s attitude toward nature may be importantly connected with virtues or human excellences. The question is, ‘what sort of person would destroy the natural environment—or even see its value solely in cost-benefit terms?’ The answer I suggest is that willingness to do so may well reveal the absence of traits which are a natural basis for a proper humility, self-acceptance, gratitude, and appreciation of the good in others.”58 Hill does not argue for the intrinsic worth of nature, probably because most philosophers reject this claim, and he does not need to persuade them otherwise to make his point. He claims that a love for nature is connected to other human virtues, which are well accepted in ethics. This, he says, is convincing evidence that loving nature is as reasonable as these other virtues are. Being Grateful As a counterargument to those who claim that nature only has use value, Hill affirms that good persons cherish things for their own sake. “[I]f someone really took joy in the natural environment, but was prepared to blow it up as soon as sentient life ended, he would lack this common human tendency to cherish what enriches our lives. While this response is not itself a moral virtue, it may be a natural basis of the virtue we call ‘gratitude.’ People who have no tendency to cherish things that give them pleasure may be poorly disposed to respond gratefully to persons who are good to them.”59 Another moral philosopher, Bryan G. Norton, addresses the same issue by telling a story about a young girl picking up sand dollars on a beach. When he asked her what she planned to do with them, she said she was going to bleach them and then sell them to tourists. The sand dollars had only economic (use) value for her, and Norton admits he was unable to think of a way to persuade her that she might be a better person if she could appreciate the sand dollars as they are, rather than as commodities that would bring her a little spending money.60 Later, Norton realized he might have encouraged her to give more value to the sand dollars—as wondrous living creatures, rather than as dead market commodities—by talking with her about using our human freedom wisely. 10 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). The freedom to collect sand dollars “and to propel ourselves about the countryside by burning petroleum are all fragile freedoms,” he writes, “that depend on the relatively stable environmental context in which they have evolved. If I could, then, have used the incident on the beach . . . to illustrate for her the way in which our activities—just like the activities of sand dollars—are possible, and gain meaning and value, only in a larger [environmental] context, I would have progressed a good way toward the goal of getting the little girl to put most of the sand dollars back.” Then, perhaps, the young girl “might have killed some sand dollars to study them, but she would still have respected sand dollars as living things with a story to tell.”61 This anthropocentric argument for respecting and appreciating nature rests on the virtue of being grateful for a stable environment, because such an environment is crucial for the exercise of our freedom—one of our most precious values. If we see the wonders of the natural world, Norton argues, we can hardly help but be grateful for the opportunities it offers us, and this sense of gratitude may motivate us to protect our natural environment.62 Summary The natural law and Tao traditions look to nature to learn how we should live. There is tension in this teleological way of thinking between resisting and obeying unjust authority, as a way of affirming natural law, and between promoting the virtue of moderation or the virtues of humility, faith, hope, and love. Yet there is agreement that good habits make good persons, and that happiness requires civic virtues and cooperating for the common good. Harmony, rather than happiness, is the way of life in the Tao tradition. The Tao Te Ching finds this goal in the changing patterns of nature, and the key to all virtue is the way that water wears down stone. Confucius agrees that we should respond with humility to those who misuse their power, in order to shame and change them, and he promotes balance in ceremonies to secure the public virtue of civility. The assertive Western virtues of courage, industry, and perseverance have been promoted around the world in stories, philosophical arguments, and Christian preaching. Today, however, the natural law tradition affirming higher ethical standards—expressed in secular and religious stories that verify the virtues of frugality, gratitude, and integrity—is being reinterpreted to support a more ecological way of life. The Catholic Church and most Protestant denominations and churches now proclaim that we should be responsible stewards, because God has entrusted humanity with care for the earth and its creatures.63 Christian teaching also expresses a concern for the poor, which is often ignored in secular discussions of environmental ethics. Many Christians support economic justice as well as healing the earth. Folk tales like Cinderella and Johnny Appleseed often include religious images and illustrate virtues that bear on our relationship with nature. The hope of Cinderella confirms that goodness and integrity will win out in the end, and the faith of Johnny Appleseed verifies that living with gratitude and frugality may lead to happiness. Will the creators of Bob the Builder succeed in transforming a story about machines and construction into a tale that inspires children to reduce, reuse, and recycle? Will this children’s program effectively promote the virtues of integrity, gratitude, and frugality?64 Will other attempts to encourage respect and gratitude for nature realize this goal? These moral arguments, stories, and religious teachings all suggest that, in protecting the environment, “our final appeal may lie, unabashedly, in apprehension, rather than in anything like formal deduction from general principles. With right training we apprehend that a person who cares about nature is a better person, other things being equal, than one who does not.”65 Questions (Always Explain Your Reasoning) 11 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). 1. If you feel life has purpose, how does this shape your character? If you feel life has no purpose, how do you decide who you should be? 2. Analyze humility using three of the perspectives summarized in this chapter, and then consider whether this virtue is relevant for doing environmental ethics. 3. How do the Tao and natural law traditions differ in ascribing value to nature? How might these differences be reflected in varied ecological lifestyles? 4. “To protect the environment, we must control population growth.” What is the reasoning behind this conclusion? How is double effect reasoning used to oppose it? 5. Do you think persons who are grateful for what they have are more likely to take care of the natural environment than those who believe they deserve what they have? NOTES 1. These points are an edited version of four points made by Christopher D. Stone, Earth and Other Ethics, 191–192. Stone uses the geometrical notion of different planes to argue for a pluralist approach to ethics. He suggests “that of the several planes on which moral discourse is conducted, some are drawn to accent what is required for actions; others, for character.” 2. See Robert Traer and Harlan Stelmach, Doing Ethics in a Diverse World, chapter 5, for a more detailed presentation of the natural law and Tao traditions. 3. Plato, Apology, http://www.philosophypages.com/hy/2d.htm. 4. Plato Apology, translated by Benjamin Jowett, http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html. 5. An introduction to Aristotle, http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/aristotle.html. 6. An introduction to Aquinas, http://www.philosophypages.com/ph/aqui.htm. 7. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html. 8. “Contraception is ‘any action which, either in anticipation of the conjugal act [sexual intercourse], or in its accomplishment, or in the development of its natural consequences, proposes, whether as an end or as a means, to render procreation impossible’ (Humanae Vitae 14). This includes sterilization, condoms and other barrier methods, spermicides, coitus interruptus (withdrawal method), the Pill, and all other such methods.” http://www.catholic.com/tracts/birth-control. 9. Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching, translation by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English, number 21. 10. The Way of Life, translation of the Tao Te Ching by R. B. Blakney, 91, number 38. 11. The Sayings of Confucius, translation by James R. Ware 36, number 4:14. 12. Ibid., 47, number 6:18. 13. Lao Tze, Tao De Ching, numbers 43 and 8, http://www.chinapage.com/gnl.html. A rendition by Peter A. Merel based on translations by Robert G. Henricks, Lin Yutang, D. C. Lau, Ch’u Ta-Kao, Gia-Fu Feng; and Jane English, Richard Wilhelm, and Aleister Crowley. 14. Ibid., number 37. 15. Ibid., number 5. 16. Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching, number 67. 17. “Cinderella,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinderella. Ai-Ling Louie, Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story from China, is beautifully illustrated by Ed Young. 12 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). 18. “Cinderella,” http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0510a.html#perrault. In the German Grimm brothers’ versions of the story, the miracles are attributed to God and the spiritual power of Cinderella’s dead mother. In the 1812 tale by the Grimm brothers, the tree that Cinderella plants over her mother’s grave provides her party dress and slippers, and in the 1857 account a white bird in this tree performs the miracle. 19. At http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Appleseed. “Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero” appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine LXIV (1871): 833. 20. Henry Howe, Richland County: Howe’s Historical Collections of Ohio, 485, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Appleseed. 21. An Indiana obituary notes that John Chapman “devoutly believed that the more he endured in this world the less he would have to suffer and the greater would be his happiness hereafter—[so] he submitted to every privation with cheerfulness.” See “Obituaries,” The Fort Wayne Sentinel 67, no. 81 (March 22, 1845), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Appleseed. 22. Luke 10:25–37. 23. The story of the Great Commandment is in three New Testament gospels: Matthew 22:34–40, Mark 12:28–34, and Luke 10:25–28. The parable of the Good Samaritan is in Luke 10:29–37, as a response to a question from a lawyer: “Who is my neighbor?” 24. “NMCCB Statement on the Environment: Partnership for the Future,” November 14, 1991, http://www.archdiocesesantafe.org/ABSheehan/Bishops/BishStatements/98.5.11.Environment.html. 25. Ibid. 26. Ibid. 27. Ibid. 28. Ibid. 29. Ibid. The full text of the canticle, which is often called the Canticle of Brother Sun, is at http://www.franciscanarchive.org/patriarcha/opera/canticle.html. 30. Ibid. 31. “Renewing the Earth: An Invitation to Reflection and Action on the Environment in Light of Catholic Social Teaching,” A Pastoral Statement of the US Catholic Conference, November 14, 1991, Justice, Peace and Human Development, US Conference of Catholic Bishops, http://www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/human-life-anddignity/environment/renewing-the-earth.cfm. 32. See Global Climate Change: A Plea for Dialogue, Prudence, and the Common Good (2001), http://www.usccb.org/sdwp/international/globalclimate.htm. 33. Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate, quoting John Paul II, Encyclical Letter Centesimus Annus, 36: loc. cit., 838–840, http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-inveritate_en.html. 34. Ibid. 35. Pope Benedict XVI, Message for the Celebration of the World Day of Peace (January 1, 2010), http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/messages/peace/documents/hf_ben-xvi_mes_20091208_xliii-worldday-peace_en.html. 36. “Evangelicals and the Environment,” Religion & Ethics (January 13, 2006), http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week920/cover.html. 37. See “Progressive Christian Beliefs,” http://progressivetheology.wordpress.com. 38. There are, of course, differences among Protestants, as well as distinctions between Protestant and Catholic ethical reasoning. See Lisa H. Sideris, Environmental Ethics, Ecological Theology, and Natural Selection. 13 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). 39. Christine Schwartz, a shopper in a Christian bookstore in Lynchburg, Virginia. Her statement refers to the text from the Revelation of John in the New Testament that is cited in Catholic teaching, but Catholic teaching interprets this passage as referring to a renewal of life in history and nature. Evangelical Protestants see this text as prophecy of eternal life with God, after history is over and the natural world is transformed. “Evangelicals and the Environment,” Religion & Ethics (January 13, 2006), http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week920/cover.html. 40. Ibid. Rev. Richard Cizik, who in 2008 was vice president for governmental affairs of the National Association of Evangelicals, in 2011 was president of Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good. 41. “Evangelical Climate Initiative,” http://www.christiansandclimate.org. 42. Ibid. 43. Ibid. 44. Lynn White, Jr., “Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis,” Science 155 (1967): 1203–1207, in David Schmidtz and Elizabeth Willott, eds., Environmental Ethics, 14. “The forces of democracy, technology, urbanization, increasing individual wealth, and an aggressive attitude toward nature seem to be directly related to the environmental crisis now being confronted in the Western world. The Judeo-Christian tradition has probably influenced the character of each of these forces: However, to isolate religious tradition as a cultural component and to contend that it is the ‘historical root of our ecological crisis’ is a bold affirmation for which there is little historical or scientific support.” Lewis W. Moncrief, “The Cultural Basis of Our Environmental Crisis,” Science 170 (1970), in Louis P. Pojman and Paul Pojman, eds., Environmental Ethics, 27. 45. See Marc Lacey, “US Churches Go ‘Green’ for Palm Sunday,” New York Times, April 1, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/01/world/americas/01palm.html. 46. Movies in 2000 and 2002 and a television miniseries in 2005 renewed these stories for a new audience. “Little House on the Prairie,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_House_on_the_Prairie. 47. The story of Karen Silkwood, who was contaminated by plutonium in the plant where she was working and then tried to expose this environmental danger, was made into a movie starring Meryl Streep. See Karen Silkwood, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karen_Silkwood. 48. At http://www.bobthebuilder.com/usa/all_you_need_to_know_about_the_show.htm. 49. “The Green Workplace” (December 2, 2007), http://www.thegreenworkplace.com/2007/12/bobs-on-job-too.html. 50. PBS, Bob the Builder (April 1, 2007). 51. The subheading of a CBS News report reads, “The Big-Spending Ways of the ‘80s Are Out as Frugality Comes into Fashion.” See “Is Cheap Now Chic?” CBS News (April 4, 2008), http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/03/eveningnews/main3992908.shtml. 52. Buddhist teaching places this virtue in the context of communal living, as chapter 6 explains. “Buddhism commends frugality as a virtue in its own right.” Lily de Silva, “The Buddhist Attitude Toward Nature,” in K. Sandell, ed., The Buddhist Attitude Towards Nature, in Pojman and Pojman, Environmental Ethics, 320. 53. “Johnny Appleseed,” Sing Along with Me: A Collection of Traditional Guide, Scout and Campfire Songs, http://songs-with-music.freeservers.com/JohnnyAppleseed.html. The words in verse two are altered slightly to improve the English. 54. “The Ecological Footprint is an ecological resource management tool that measures how much land and water area a human population requires to produce the resources it consumes and to absorb its wastes under prevailing technology. . . . Today, humanity’s Ecological Footprint is over 23 percent larger than what the planet can regenerate.” Global Footprint Network: Advancing the Science of Sustainability, “Ecological Footprint: Overview,” http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFn/page/footprint_basics_overview/. Carbonfund.org calculates your carbon emissions and allows you to invest in carbon emission–reducing activities to offset your “carbon footprint” (http://www.carbonfund.org). 14 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013). 55. In the mid-1980s Christopher D. Stone asked: “What are the virtues of human character and of the earth? What makes a person or a lake ‘good’ or whatever else may be significant?” Earth and Other Ethics, 199. Now the “integrity” of ecosystems is recognized in both environmental ethics and law. See chapter 6. 56. “Cinderella,” Grimms’ Fairy Tales, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/grimm/cinderella.html. 57. Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger, Break Through, 153. 58. Thomas E. Hill, Jr., “Ideals of Human Excellence and Preserving Natural Environments,” Environmental Ethics 5 (1983): 211–224, in Schmidtz and Willott, Environmental Ethics, 189. 59. Ibid., 197. “A nonreligious person unable to ‘thank’ anyone for the beauties of nature may nevertheless feel ‘grateful’ in a sense; and I suspect that the person who feels no such ‘gratitude’ toward nature is unlikely to show proper gratitude toward people.” 60. Bryan G. Norton, “The Environmentalists’ Dilemma: Dollars and Sand Dollars,” Toward Unity Among Environmentalists, 3–13, in Schmidtz and Willott, Environmental Ethics, 494–500. 61. Bryan G. Norton, “Fragile Freedoms,” Toward Unity Among Environmentalists, in Schmidtz and Willott, Environmental Ethics, 502. 62. For an alternative argument that we are more likely to value individual animals for their aesthetic value, rather than as an endangered species, see Lilly-Marlene Russow, “Why Do Species Matter?” Environmental Ethics 3 (1981), in Pojman and Pojman, Environmental Ethics, 269–276. This argument was confirmed during a Reading Rainbow program on PBS (April 24, 2008), when a young reader promoting a book on endangered species said, “We need to save endangered species, because all of the animals make our world more beautiful.” 63. James Trefil acknowledges that a religious or philosophical appeal to stewardship is, for many people, “the argument that seems to carry the most weight,” but adds that it is “impossible to save everything, and that means that hard choices still have to be made. It’s difficult to make those choices if you have a belief that, in effect, assigns infinite value to every species on the planet.” Human Nature, 123. 64. “These days, recycle, reduce and reuse is the new mantra in schools as educators, politicians and parents push for increased environmental education and ecological awareness in California classrooms.” Jill Tucker, “Three R’s Go Green, Starting with Recycle,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 15, 2008, W-2, http://www.sfgate.com/cgibin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/08/15/BAC71230JN.DTL. 65. Stone, Earth and Other Ethics, 199. 15 Text from Chapter 5 of Doing Environmental Ethics by Robert Traer (Westview Press, 2013).