ethics - IDt - Mälardalens högskola

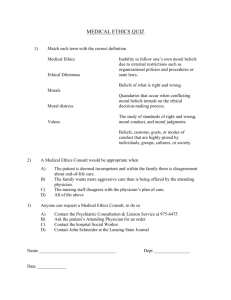

advertisement

DVA215 INFORMATION - KUNSKAP - VETENSKAP GRUNDLÄGGANDE VETENSKAPSTEORI Agent-baserade modeller. Generativ kunskap. Simulering Gordana Dodig-Crnkovic Akademin för innovation, design och teknik, Mälardalens högskola 1 KUNSKAPSGENERATION: VÄRLDEN SOM INFORMATION FÖR EN AGENT Bilden från: http://www.alexeikurakin.org 2 http://www.alexeikurakin.org/ Hebbs teori: "celler som avfyras tillsammans, sammankopplas" (eng. "cells that fire toghether, wire togher"). LÄRANDE OCH KUNSKAP Barnet föds med nervsystemet och hjärnan och förmågan att ta olika intryck från världen. 3 INFORMATIONSNÄTVERK ORGANISMER MÄNNISKAN CELLER SOCIALA GRUPPER EKOLOGIER MOLEKYLER PLANETSYSTEM ATOMER ELEMENTÄRA PARTIKLAR GALAXER UNIVERSUM http://www.media.mit.edu/events/fall11/networks Networks understanding networks, MIT conference http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ni_A2bAkUww&feature=relmfu Albert-László Barabási 4 Links http://www.idt.mdh.se/personal/gdc/ http://www.mdh.se/university/organization/boards/Ethics 5 Professional Ethics Course Information about the course: http://www.idt.mdh.se/kurser/cd5590 http://www.idt.mdh.se/kurser/ethics/ [Website provides ethics resources including case studies and contextualized scenarios in applied/professional ethics, working examples of applied ethical problems used in teaching to highlight relevant ethical principles, materials on informed consent, confidentiality, assessment, privacy, trust and similar. ] 6 CONTENT – Identifying Ethical Issues Basic Moral Orientations Ethical Relativism, Absolutism, and Pluralism Immanuel Kant The Ethics of Duty (Deontological Ethics) Utilitarianism Rights Justice The Ethics of Character: Virtues and Vices Egoism Moral Reasoning and Gender Environmental Ethics Professional Issues Plagiarism Criticism of the Sources Conclusions 7 Identifying Ethical Issues Based on: Lawrence M. Hinman, Ph.D. Director, The Values Institute University of San Diego 8 Ethics and Morality The terms ethics and morality are often used interchangeably - indeed, they usually can mean the same thing, and in casual conversation there isn't a problem with switching between one and the other. However, there is a distinction between them in philosophy! 9 Ethics and Morality Etymology Morality and ethics have same roots, mores which means manner and customs from the Latin and etos which means custom and habits from the Greek. Robert Louden, Morality and Moral Theory 10 Ethics and Morality Strictly speaking, morality is used to refer to what we would call moral standards and moral conduct while ethics is used to refer to the formal study of those standards and conduct. For this reason, the study of ethics is also often called "moral philosophy." 11 Ethics and Morality Morality: first-order set of beliefs and practices about how to live a good life. Ethics: a second-order, conscious reflection on the adequacy of our moral beliefs. 12 ETHICS Philosophers commonly distinguish: descriptive ethics, the factual study of the ethical standards or principles of a group or tradition; normative ethics, the development of theories that systematically denominate right and wrong actions; applied ethics, the use of these theories to form judgments regarding practical cases; and meta-ethics, careful analysis of the meaning and justification of ethical claims Source: www.ethicsquality.com/philosophy.html 13 SOCIETY VALUES ETHICS LAW 14 MORAL Identifying Moral Issues Moral concerns are unavoidable in life. They are not always easy to identify and define. 15 Ethics as an Ongoing Conversation Professional discussions of ethical issues in journals. We come back to ideas again and again, finding new meaning in them. See http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/e/ethics.htm 16 The Focus of Ethics Ethics as the Evaluation of Other People’s Behavior We are often eager to pass judgment on others Ethics as the Search for Meaning and Value in Our Own Lives 17 Ethics as the Evaluation of Other People’s Behavior Ethics often used as a weapon Hypocrisy Possibility of knowing other people The right to judge other people The right to intervene Judging and caring 18 Ethics as the Search for Meaning and Value in Our Own Lives Positive focus Aims at discerning what is good Emphasizes personal responsibility for one’s own life 19 What to Expect from Ethics Identification and description of an issue Explanation Support in deliberation 20 The Point of Ethical Reflection Ethics as the evaluation of other people’s behavior Ethics as the search for the meaning of our own lives 21 Basic Moral Orientations 22 On what basis do we make moral decisions? (1) Divine Command Theories -- “Do what the Bible tells you” or the Will of God Utilitarianism -- “Make the world a better place” Virtue Ethics -- “Be a good person” The Ethics of Duty -- “Do your duty” Immanuel Kant’s Moral Theory Ethical Egoism -- “Watch out for #1” 23 On what basis do we make moral decisions? (2) The Ethics of Natural and Human Rights -- “...all people are created ...with certain unalienable rights” Social Contract Ethics Moral Reason versus Moral Feeling Evolutionary Ethics 24 Divine Commands Being good is equivalent to doing whatever the Bible--or the Qur’an or some other sacred text or source of revelation tells you to do. “What is right” equals “What God tells me to do.” 25 Utilitarianism (Consequentialism) Hedonistic utilitarianism: Seeks to reduce suffering and increase pleasure or happiness Epicurus (341-270 BC) Greek Epicurus (341-270 BC) “We count pleasure as the originating principle and the goal for the blessed life”. (Letter to Menoeceus) Frances Hutcheson (1694-1747) Irish “The action is best, which procures the greatest happiness for the greatest number; and that worst, which in like manner, occasions misery.” (An Inquiry Concerning Moral Good and Evil, 3.8) Bentham’s Utilitarian Calculus Mill’s Utilitarianism John Stuart Mill 1806-1873 “Actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote [general] happiness; wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of [general] happiness. (Utilitarianism, 2) http://www.utilitarism.net/ (in Swedish) 26 Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) Virtue Ethics One of the oldest moral theories. Ancient Greek epic poets and playwrights Homer and Sophocles describe the morality of their heroes in terms of virtues and vices. Plato - cardinal virtues: wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. Even accepted by early Plato (427-347 BCE) Christian theologians. Aristotle: The Nichomachean Ethics Morality is a matter of being a good person, which involves having virtuous character traits. Seeks to develop individual character Aristotle (384-322 BCE.) 27 The Ethics of Duty (Deontological* Ethics) Ethics is about doing your duty. Cicero (stoic): On duties (De Officiis) http://www.stoics.com/cicero_book.html Medieval philosophers: duties to God, self and others Kant: only moral duties to self and others Samuel von Pufendorf (1632-1694): Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 - 43) BC moral duties spring from our instinctive drive for survival – we should be sociable in order to survive. Intuitionism: we don’t logically deduce moral duties, we know them as thy are! For each duty there is a corresponding virtue. * ‘deon’ = duty Immanuel Kant 1724-1804 28 Immanuel Kant’s Moral Theory Human reason makes moral demands on our lives The categorical imperative: Act so that the maxim [determining motive of the will] may be capable of becoming a universal law for all rational beings." We have moral responsibility to develop our talents 29 Immanuel Kant 1724-1804 Ethical Egoism Says the only person to look out for is yourself Ayn Rand, The Ethics of Selfishness Well known for her novels, especially Atlas Shrugged* Ayn Rand sets forth the moral principles of “Objectivism”, the philosophy that holds that man's life--the life proper to a rational being--as the standard of moral values. It regards altruism as incompatible with man's nature, with the requirements of his survival, and with a free society. *shrug - to raise the shoulders, especially as a gesture of doubt, disdain, or indifference 30 The Ethics of Rights The most influential moral notion of the past two centuries Established minimal conditions of human decency Human rights: rights that all humans supposedly possess. natural rights: some rights are grounded in the nature rather than in governments. moral rights, positive rights, legal rights, civil rights 31 The Ethics of Rights Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) right from nature implies a liberty to protect myself from attack in any way that I can. John Locke (1632-1704) principal Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) natural rights: life, health, liberty and possessions. John Locke (1632-1704) 32 Evolutionary Ethics Human social behavior is an extended development of 33 biological evolution. Evolutionary ethics: moral behavior is that which tends to aid in human survival. Darwin: Origin of Species focuses on the evolutionary mechanisms of nonhuman animals. Biologists and philosophers of nineteenth century attempted to frame morality as an extension of the evolutionary biological process. Problem of the theory: what is progress? What is good? Any signs of moral improvement since Plato? Moral Reason versus Moral Feeling Morality is strictly a matter of rational judgment: Samuel Clarke (1675-1729) Since time of Plato: moral truths exist in a spiritual realm. Moral truths like mathematical truths are eternal. Morality is strictly a matter of feeling (emotion): David Hume (1711-1729) We have a moral sense Samuel Clarke (1675-1729) David Hume (1711-1729) 34 Ethical Relativism, Absolutism, and Pluralism Based on: Lawrence M. Hinman, Ph.D. Director, The Values Institute University of San Diego 35 Classical Ethical/Cultural Relativism The Greek Skeptics (1) Xenophanes (570-475 BCE) “Ethiopians say that their gods are flat-nosed and dark, Thracians that theirs are blue-eyed and red-haired. If oxen and horses and lions had hands and were able to draw with their hands and do the same things as men, horses would draw the shapes of gods to look like horses and oxen to look like ox, and each would make the god’s bodies have the same shape as they themselves had.” The historian Heroditus(484-425 BCE) “Everyone without exception believes his own native customs, and the religion he was brought up in, to be the best.” 36 Classical Ethical/Cultural Relativism The Greek Skeptics (2) Sextus Empiricus (fl. 200 CE) Gives example after example of moral standards that differ from one society to another, such as attitudes about homosexuality, incest, cannibalism, human sacrifice, the killing of elderly, infanticide, theft, consumption of animal flesh… Sextus Empiricus concludes that we should doubt the existence of an independent and universal standard of morality, and instead regard moral values as the result of cultural preferences. 37 Later Ethical Relativism (1) French philosopher Michael de Montaigne (1533-1592): Custom has the power to shape every possible kind of cultural practice. Although we pretend that morality is a fixed feature of nature, morality too is formed through custom. Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) “fashion, vogue, custom, and law are the chief foundation of all moral determinations” 38 Later Ethical Relativism (2) The fact of moral diversity We should not pass judgment on practices in other cultures when we don’t understand them Sometimes reasonable people may differ on what’s morally acceptable 39 Insights of Ethical Relativism Ethical relativism has several important insights: The fact of moral diversity The need for tolerance and understanding We should not pass judgment on practices in other cultures when we don’t understand them Sometimes reasonable people may differ on what’s morally acceptable 40 Ethical Relativism: Limitations Presupposes an epistemological solipsism* Is unhelpful in dealing with overlaps of cultures--precisely where we need help. Commerce and trade Media World Wide Web [*Solipsism - belief in self as only reality: the belief that the only thing somebody can be sure of is that he or she exists, and that true knowledge of anything else is impossible] 41 Ethical Relativism: Overlapping Cultures, 1 Ethical relativism suggests that we let each culture live as it sees fit. This is only feasible when cultures don’t have to interact with one another. 42 Ethical Relativism: Overlapping Cultures, 2 The challenge of the coming century is precisely overlapping cultures: 43 Multinational corporations International media--BBC, MTV, CNN International sports--Olympics World Wide Web Ethical Relativism: Overlapping Cultures, 3 The actual situation in today’s world is much closer to the diagram at the right. 44 Ethical Relativism: Our Global Village, 5 What if our world was a village of 100 people? 58 would be Asians, 15 Europeans, 13 would come from the Western Hemisphere, 12 would be Africans 70 would be non-white 67 would be non-Christian (33 Christians; 18 Moslems; 14 Hindus; 6 Buddhists; 5 atheists; 3 Jews; 24 other.) 16 would speak Chinese; 8 English; 8 Hindi; 6 Spanish; 6 Russian; and 5 Arabic. 50 % of the wealth would be held by 6 people. 70 could not read and only one would have a university education. 45 http://www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/103/3areaoutline.htm Ethical Relativism: A Self-Defensive Position Ethical relativism maintains that we cannot make moral judgments about other cultures The corollary of this is that we are protected in principle against the judgments made by other cultures 46 How Much Dressed? Naked? Rembrandt Monk Reading, 1661 Fencer – protective suit Apollo Belvedere 320 BCE Taliban law requires women in Afghanistan to wear a chador or burqa that covers the face and entire body. 47 A proper dress? Amazonian indigenous woman with child From the solitude of the Holy Cross Abbey in Virginia, a monk works on the Internet, 21th century Nuns uniforms How Much Dressed? Naked? Dieric Bouts - Madonna and Child 48 Leonardo da Vinci Lady with an Ermine 1483-90 Holbein’s Family 1528 Arguments Against Ethical Relativism There Are Some Universals in Codes of Behavior across Cultures Three core common values: caring for children truth telling (trust) and prohibitions against murder The society must guard against killing, abusing the young, lying etc. that are at its own peril. Were the society not to establish some rules against such behaviors, the society itself would cease to exist. 49 Ethical Objectivism The view that moral principles have objective validity whether or not people recognize them as such, that is, moral rightness or wrongness does not depend on social approval, but on such independent considerations as whether the act or principle promotes human flourishing or ameliorates human suffering. What is moral depends on the fabric of human nature. 50 Plato (427-347 BCE) Immanuel Kant 1724-1804 Ethical Absolutism/Universalism Ethical Absolutism: Morality is eternal and unchanging and holds for all rational beings at all times and places. In other words, moral right and wrong are fundamentally the same for all people. (Morality is considered different than mere etiquette). There is only one correct answer to every moral problem. A completely absolutist ethic consists of absolute principles that provide an answer for every possible situation in life, regardless of culture. 51 Ethical Absolutism Absolutism comes in many versions--including the divine right of kings Absolutism is less about what we believe and more about how we believe it Common elements: 52 There is a single Truth Their position embodies that truth Louis XIV (1638 – 1715) Louis the Great, The Sun King Ethical Absolutism Ethical absolutism gets some things right We need to make judgments Certain things are intolerable But it gets some things wrong, including: 53 Our truth is the truth We can’t learn from others Ethical Pluralism (1) Combines insights of both relativism and absolutism: 54 The central challenge: how to live together with differing and conflicting values Fallibilism: recognizes that we might be mistaken Sees disagreement as a possible strength Ethical Pluralism (2) Moral pluralists maintain that there are moral truths, but they do not form a body of coherent and consistent truths in the way that one finds in the science or mathematics. Moral truths are real, but partial. Moreover, they are inescapably plural. There are many moral truths, not just one–and they may conflict with one another. 55 Ethical Pluralism (3) Pluralism is the cultural manifestation of ethical individualism; it is implied by the respect for the human being, for what it means to be human. We have differing moral perspectives, but we must often inhabit a common world. 56 Ethical Pluralism (4) Ethical pluralism offers three categories to describe actions: Prohibited: those actions which are not seen as permissible at all Absolutism sees the importance of this Tolerated: those actions and values in which legitimate differences are possible Relativism sees the importance of this Ideal: a moral vision of what the ideal society would be like 57 Ethical Pluralism (5) For each action or policy, we can place it in one of three regions: Ideal--Center Permitted--Middle 58 Respected Tolerated Prohibited--Outside Five Questions What is the present state? What is the ideal state? What is the minimally acceptable state? How do we get from the present to the minimally acceptable state? How do we get from the minimum to the ideal state? 59 Immanuel Kant THE ETHICS OF DUTY (Deontological* Ethics) * ‘deon’ = duty 60 Living by Rules Most of us live by rules much of the time. Some of these are what Kant called Categorical Imperatives. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) 61 Categorical Imperatives Always act in such a way that the maxim of your action can be willed as a universal law of humanity. --Immanuel Kant 62 The Ethics of Respect (1) One of Kant’s most lasting contributions to moral philosophy was his emphasis on the notion of respect (Achtung). 63 The Ethics of Respect (2) Respect has become a fundamental moral concept in contemporary West There are rituals of respect in almost all cultures. Two central questions: What is respect? Who or what is the proper object of respect? 64 Kant on Respect “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.” 65 Kant on Respecting Persons Kant brought the notion of respect (Achtung) to the center of moral philosophy for the first time. To respect people is to treat them as ends in themselves. He sees people as autonomous, i.e., as giving the moral law to themselves. The opposite of respecting people is treating them as mere means to an end. 66 Using People as Mere Means The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments 67 More than four hundred African American men infected with syphilis went untreated for four decades in a project the government called the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male. Continued until 1972 Treating People as Ends in Themselves What are the characteristics of treating people as ends in themselves? Giving them relevant and accurate information Allowing them freedom of choice 68 Additional Cases Plant Closing Firing Long-Time Employees Medical Experimentation on Prisoners Medical Donations by Prisoners Medical Consent Forms 69 What Is the Proper Object of Respect? For Kant, the proper object of respect is the will. Hence, respecting a person involves issues related to the will-knowledge and freedom. Other possible objects of respect: 70 Feelings and emotions The dead Animals The natural world Self-Respect Is lack of proper self-respect a moral failing? The Deferential* Wife See article by Tom Hill, “Servility and Self-Respect” *Deferential = Respectful, considerate 71 Self-Respect Aristotle and Self-Love 72 What is the difference between self-respect and self-love? Clearly, there is at least a difference in the affective element. The Kantian Heritage What Kant Helped Us to See Clearly The Admirable Side of Acting from Duty The person of duty remains committed, not matter how difficult things become. The Evenhandedness of Morality Kantian morality does not play favorites. Respecting Other People 73 The notion of treating people as ends in themselves is central to much of modern ethics. The Kantian Heritage Critique of Kant´s Deontology The Neglect of Moral Integration The person of duty can have deep and conflicting inclinations and this does not decrease moral worth— indeed, it seems to increase it in Kant’s eyes. The Role of Emotions For Kant, the emotions are always suspect because they are changeable. 74 The Kantian Heritage Critique of Kant´s Deontology The Place of Consequences in the Moral Life 75 In order to protect the moral life from the changing of moral luck, Kant held a very strong position that refused to attach moral blame to individuals who were acting with good will, even though some indirect bad consequences could be foreseen. The Kantian Heritage Conclusion Overall, after two hundred years, Kant remains an absolutely central figure in contemporary moral philosophy, one from whom we can learn much even when we disagree with him. 76 Utilitarianism 77 Basic Insights of Utilitarianism The purpose of morality is to make the world a better place. We should do whatever will bring the most benefit to all of humanity. 78 The Purpose of Morality The utilitarian has a simple answer to the question of why morality exists at all: The purpose of morality is to guide people’s actions in such a way as to produce a better world. Consequently, the emphasis in utilitarianism is on consequences, not intentions. (At times, the road to hell is pawed with good intentions) 79 Fundamental Imperative The fundamental imperative of utilitarianism is: Always act in the way that will produce the greatest overall amount of good in the world. 80 The Emphasis on the Overall Good Utilitarianism is a demanding moral position that often asks us to put aside self-interest for the sake of the whole. It always asks us to do the most, to maximize utility, not to do the minimum. It asks us to set aside personal interest. 81 The Dream of Utilitarianism: Bringing Scientific Certainty to Ethics Utilitarianism offers a powerful vision of the moral life, one that promises to reduce or eliminate moral disagreement. If we can agree that the purpose of morality is to make the world a better place; and If we can scientifically assess various possible courses of action to determine which will have the greatest positive effect on the world; then We can provide a scientific answer to the question of what we ought to do. 82 Standards of Utility: Intrinsic Value Many things have instrumental value, that is, they have value as means to an end. However, there must be some things which are not merely instrumental, but have value in themselves. This is what we call intrinsic value. What has intrinsic value? Four principal candidates: Pleasure - Jeremy Bentham Happiness - John Stuart Mill Ideals - George Edward Moore Preferences - Kenneth Arrow 83 Jeremy Bentham 1748-1832 Bentham believed that we should try to increase the overall amount of pleasure in the world. 84 Pleasure Criticisms Definition: The enjoyable feeling we experience when a state of deprivation is replaced by fulfillment. Advantages Easy to quantify Short duration Bodily 85 Came to be known as “the pig’s philosophy” Ignores spiritual values Could justify living on a pleasure machine or “happy pill” John Stuart Mill 1806-1873 Bentham’s godson Believed that happiness, not pleasure, should be the standard of utility. 86 Happiness Advantages 87 A higher standard, more specific to humans About realization of goals Disadvantages More difficult to measure Competing conceptions of happiness Ideal Values G. E. Moore suggested that we should strive to maximize ideal values such as freedom, knowledge, justice, and beauty. The world may not be a better place with more pleasure in it, but it certainly will be a better place with more freedom, more knowledge, more justice, and more beauty. Moore’s candidates for intrinsic good remain difficult to quantify. G. E. Moore 1873-1958 88 Preferences Kenneth Arrow, a Nobel Prize winning Stanford economist, argued that what has intrinsic value is preference satisfaction. The advantage of Arrow’s approach is that, in effect, it lets people choose for themselves what has intrinsic value. It simply defines intrinsic value as whatever satisfies an agent’s preferences. It is elegant and pluralistic. KENNETH J. ARROW Stanford University Professor of Economics (Emeritus) 89 May this help? Lets make everyone happy! Happy pill as a universal solution? 90 The Utilitarian Calculus Math and ethics finally merged: all consequences must be measured and weighed! Units of measurement: Hedons: positive Dolors: negative 91 What do we calculate? Hedons/dolors defined in terms of 92 Pleasure Happiness Ideals Preferences What do we calculate? For any given action, we must calculate: 93 How many people will be affected, negatively (dolors) as well as positively (hedons) How intensely they will be affected Similar calculations for all available alternatives Choose the action that produces the greatest overall amount of utility (hedons minus dolors) How much can we quantify? Pleasure and preference satisfaction are easier to quantify than happiness or ideals Two distinct issues: Can everything be quantified? The danger: if it can’t be counted, it doesn’t count. Are quantified goods necessarily commensurable? Are a fine dinner and a good night’s sleep commensurable? 94 “…the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” Utilitarianism doesn’t always have a cold and calculating face—we perform utilitarian calculations in everyday life. 95 Criticisms of Utilitarianism 1. Responsibility Utilitarianism suggests that we are responsible for all the consequences of our choices. The problem is that sometimes we can not foresee consequences of other people’s actions that are taken in response to our own acts. Are we responsible for those actions, even though we don’t choose them or approve of them? 96 Criticisms of Utilitarianism 2. Integrity Utilitarianism often demands that we put aside self- interest. Sometimes this may mean putting aside our own moral convictions. Integrity may involve certain identity-conferring commitments, such that the violation of those commitments entails a violation of who we are at our core. 97 Criticisms of Utilitarianism 3. Intentions Utilitarianism is concerned almost exclusively about consequences, not intentions. There is a version of utilitarianism called “motive utilitarianism,” developed by Robert Adams, that attempts to correct this. 98 Criticisms of Utilitarianism 4. Moral Luck By concentrating exclusively on consequences, utilitarianism makes the moral worth of our actions a matter of luck. We must await the final consequences before we find out if our action was good or bad. This seems to make the moral life a matter of chance, which runs counter to our basic moral intuitions. 99 Criticisms of Utilitarianism 5. Who does the calculating? Historically, this was an issue for the British in India. The British felt they wanted to do what was best for India, but that they were the ones to judge what that was. See Ragavan Iyer, Utilitarianism and All That Typically, the count differs depending on who does the counting 100 Criticisms of Utilitarianism 6. Who is included? When we consider the issue of consequences, we must ask who is included within that circle. Classical utilitarianism has often claimed that we should acknowledge the pain and suffering of animals and not restrict the calculus just to human beings. 101 Concluding Assessment Utilitarianism is most appropriate for policy decisions, as long as a strong notion of fundamental human rights guarantees that it will not violate rights of minorities, otherwise it is possible to use to justify outvoting minorities. 102 Rights 103 Rights: Changing Western History Many of the great documents of the last two centuries have centered around the notion of rights. The Bill of Rights The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen The United Nation Declaration of Human Rights 104 Human Rights After the King John of England violated a number of ancient laws and customs by which England had been governed, his subjects forced him to sign the Magna Carta, or Great Charter, which enumerates what later came to be thought of as human rights. 105 Human Rights Among rights of Magna Carta were the right of the church to be free from governmental interference, the rights of all free citizens to own and inherit property and be free from excessive taxes. It established the right of widows who owned property to choose not to remarry, and established principles of due process and equality before the law. It also contained provisions forbidding bribery and official misconduct. 106 Rights: A Base for Moral Change Many of the great movements of this century have centered around the notion of rights. The Civil Rights Movement Equal rights for women Movements for the rights of indigenous peoples Children’s rights Gay rights 107 Justifications for Rights Self-evidence Divine Foundation Natural Law Human Nature 108 Self-evidence “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” Declaration of Independence July 4, 1776 109 Divine Foundation “We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for us and our Heirs for ever, That the Church of England shall be free, and shall have her whole rights and liberties inviolable. We have granted also, and given to all the freemen of our realm, for us and our Heirs for ever, these liberties underwritten, to have and to hold to them and their Heirs, of us and our Heirs for ever.” The Magna Carta, 1297 110 Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 1. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html 111 Rights-related Questions Freedom of Speech Death Penalty The Disappeared Economic & Social Rights Terrorism & Anti-Terrorism Corruption 112 Natural Law According to natural law ethical theory, the moral standards that govern human behavior are, in some sense, objectively derived from the nature of human beings. 113 Natural Law Human Nature Arguments for natural rights that appeal to human nature involve the following steps: 114 Establish that some characteristic of human nature, such as the ability to make free choices, is essential to human life. Natural Law Human Nature 115 Establish that certain empirical conditions, such as the absence of physical constraints, are necessary for the existence or the exercise of that characteristic; Conclude that people have a right to those empirical conditions. Two Concepts of Rights The distinction depends on the obligation that is placed on those who must respect your rights. Negative Rights Obliges others not to interfere with your exercise of the right. Positive Rights Obligates others to provide you with positive assistance in the exercise of that right. 116 Negative Rights Negative rights simply impose on others the duty not to interfere with your rights. The right to life, construed as a negative right, obliges others not to kill you. The right to free speech, construed as a negative right, obliges others not to interfere with your free speech 117 Positive Rights Positive rights impose on others a specific obligation to do something to assist you in the exercise of your right The right to life, construed as a positive right, obliges others to provide you with the basics necessary to sustain life if you are unable to provide these for yourself The right to free speech, construed as a positive right, obligates others to provide you with the necessary conditions for your free speech--e.g., air time, newspaper space, etc. Welfare rights are typically construed as positive rights. 118 Positive Rights: Critique Who is obligated to provide positive assistance? 119 People in general Each of us individually The state (government) The Limitations of Rights Concept Rights, Community, and Individualism Rights and Close Relationships 120 The Limitations of Rights Concept Contradicting rights: Athos and Women Greek public community is indignant at the decision recently taken by the Dutch court and at the resolution of European parliament. In January, a Greek law that allows monks from the Athos Monastery not to let women to the Holy Mount was officially declared in court as contradicting human rights. 121 The Limitations of Rights Concept Contradicting rights: Athos and Women An official response to the declaration was immediate: governmental spokesman told European human rights activists that the right of the Athos monastery republic not to let women to the Holy Mount was confirmed in the treaty of Greece-s incorporation into the European Union. 122 Concluding Evaluation Rights do not tell the whole story of ethics, especially in the area of personal relationships. Rights are always defined for groups of people (humanity, women, indigenous people, workers etc). 123 Personal Integrity vs Public Safety 124 Justice 125 Introduction All of us have been the recipients of demands of justice. My 6 year old daughter protesting, “Daddy, it’s not fair for you to get a cookie at night and I don’t.” All of us have also been in the position of demanding justice. I told the builder of my house that, since he replaced defective windows for a neighbor, he should replace my defective windows. 126 Conceptions of Justice Distributive Justice Benefits and burdens Compensatory/Recompensatory Justice Criminal justice 127 Distributive Justice The central question of distributive justice is the question of how the benefits and burdens of our lives are to be distributed. Justice involves giving each person his or her due. Equals are to be treated equally. 128 Goods Subject to Distribution What is to be distributed? 129 Income Wealth Opportunities Subjects of Distribution To whom are good to be distributed? 130 Individual persons Groups of persons Classes Basis for Distribution On what basis should goods be distributed? 131 Equality Individual needs or desires Free market transactions Ability to make best use of the goods Strict Egalitarianism Basic principle: every person should have the same level of material goods and services Criticisms Unduly restricts individual freedom May conflict with what people deserve 132 The Difference Principle More wealth may be produced in a system where those who are more productive earn greater incomes. Strict egalitarianism may discourage maximal production of wealth. 133 Welfare-Based Approaches Seek to maximize well-being of society as a whole 134 Desert*-Based Approaches Distributive systems are just insofar as they distribute incomes according to the different levels earned or deserved by the individuals in the society for their productive labors, efforts or contributions. (Feinberg) 135 *desert - förtjänst; förtjänt lön, vedergällning according to one's deserts efter förtjänst Desert*-Based Approaches Distribution is based on: Actual contribution to the social product Effort one expend in work activity Compensation to the costs Seeks to raise the overall standard of living by rewarding effort and achievement May be applied only to working adults 136 137 Try to run “Wealth Distribution”, a model that simulates the distribution of wealth. http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/models/WealthDistribution The Ethics of Character: Virtues and Vices 138 Introduction Concern for character has flourished in the West since the time of Plato, whose early dialogues explored such virtues as courage and piety*. Plato (by Michaelangelo) 139 * fromhet Two Moral Questions The Question of Action: How ought I to act? The Question of Character What kind of person ought I to be? Our concern here is with the question of character 140 An Analogy from the Criminal Justice System • As a country, we place our trust for just decisions in the legal arena in two places: Laws, which provide the necessary rules People, who (as judge and jury) apply rules judiciously • Similarly, ethics places its trust in: Theories, which provide rules for conduct Virtue, which provides the wisdom necessary for applying rules in particular instances 141 Virtue Strength of character 142 (habit) Involving both feeling, knowing and action Seeks the mean between excess and deficiency relative to us Dynamic balance Secure desirable behavior Aristotle (by Michaelangelo) The Seven Essential Virtues Defining “Moral IQ” Empathy Conscience Self-Control Respect Tolerance Fairness Kindness 143 *Aristotles cardinal virtues Wisdom* Courage* Temperance* Justice* Integrity Responsibility Honesty Virtues (1) Sphere of Existence Deficiency Attitude toward Servility self Self-deprecation Attitude toward offenses of others Attitude toward good deeds of others Ignoring them Being a Doormat Suspicion Envy Ignoring them Mean Excess Arrogance Proper Self-Love Conceit Proper Pride Egoism Self-Respect Narcissism Vanity Anger Revenge Forgiveness Grudge Understanding Resentment Gratitude Admiration Regret, Attitude toward Indifference Remorse Remorselessness our Making Amends own offenses Downplaying Self-Forgiveness Attitude toward Indifference Loyalty our friends Over indebtedness Toxic Guilt Scrupulosity Shame Obsequiousness 144 Virtues (2) Sphere of Existence Deficiency Mean Excess Attitude toward our own good deeds Belittling Disappointment Sense of Accomplishment Humility Selfrighteousness Attitude toward the suffering of others Callousness Compassion Pity “Bleeding Heart” Attitude toward the achievements of others Selfsatisfaction Complacency Competition Admiration Emulation Envy Cowardice Courage Foolhardiness Anhedonia Temperance Moderation Lust Gluttony Exploitation Respect Deferentiality Attitude toward death and danger Attitude toward our own desires Attitude toward other people 145 Two Concepts of Morality In a simplified scheme, we can contrast two approaches to the morality. Restrictive concept: Affirmative concept: 146 Child vs. adult Comes from outside (usually parents). “Don’t touch that stove burner!” Rules and habit formation are central. Adult vs. adult Comes from within (self-directed). “This is the kind of person I want to be” Virtue-centered, often modeled on ideals. Rightly-ordered Desires and the Goals of Moral Education Moral education may initially seek to control unruly desires through rules, the formation of habits, etc. Ultimately, moral education aims at forming and cultivating virtuous conduct. 147 Virtue As the Golden Mean Strength of character (virtue), Aristotle suggests, involves finding the proper balance between two extremes. Excess: having too much of something. Deficiency: having too little of something. Not mediocrity, but harmony and balance. 148 Virtue and Habit For Aristotle, virtue is something that is practiced and thereby learned—it is habit (hexis). This has clear implications for moral education, for Aristotle obviously thinks that you can teach people to be virtuous. 149 Egoism 150 Two Types of Egoism Two types of egoism: Psychological egoism Ethical egoism 151 Asserts that as a matter of fact we do always act selfishly Purely descriptive Maintains that we should always act selfishly What does it mean to be selfish? If we are selfish, do we only do things that are in our genuine selfinterest? What about the chain smoker? Is this person acting out of genuine selfinterest? In fact, the smoker may be acting selfishly (doing what he wants without regard to others) but not selfinterestedly (doing what will ultimately benefit him). 152 What does it mean to be selfish? If we are selfish, do we only do things we believe are in our selfinterest? What about those who believe that sometimes they act altruistically? Does anyone truly believe Mother Theresa was completely selfish? Think of the actions of parents. Don’t parents sometimes act for the sake of their children, even when it is against their narrow self-interest to do so? 153 Mother Theresa (1910-1997) Re-conceptualizing Psychological Egoism In addition to having two independent axes, we must distinguish between the intentions of actions and their consequences. Thus we get two graphs: Consequences Intentions Strongly intended to help others Not intended to benefit self High beneficial To others Strongly intended to benefit self Strongly intended to harm others 154 Highly harmful to self Highly beneficial to self Highly harmful to others Ethical Egoism 155 Ethical Egoism Selfishness is praised as a virtue Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness May appeal to psychological egoism as a foundation Often very compelling for high school students Ayn Rand (1905-1982). (born Alice Rosenbaum) 156 Versions of Ethical Egoism Personal Ethical Egoism “I am going to act only in my own interest, and everyone else can do whatever they want.” Individual Ethical Egoism “Everyone should act in my own interest.” Universal Ethical Egoism “Each individual should act in his or her own self interest.” 157 Altruism Unselfish concern for the welfare of others; selflessness, charity, generosity. Zoology. Instinctive cooperative behavior that is detrimental (harmful) to the individual but contributes to the survival of the species. 158 Universalizing Ethical Egoism Can the ethical egoist consistently will that everyone else follow the tenets of ethical egoism? It seems to be in one’s self-interest to be selfish oneself and yet get everyone else to act altruistically (especially if they act for your benefit). This leads to individual ethical egoism. Some philosophers such as Jesse Kalin have argued that in sports we consistently universalize ethical egoism: we intend to win, but we want our opponents to try as hard as they can! 159 Egoism, Altruism, and the Ideal World Ideally, we seek a society in which self-interest and regard for others converge—the green zone. Egoism at the expense of others and altruism at the expense of selfinterest both create worlds in which goodness and self-regard are mutually exclusive—the yellow zone. No one want the red zone, which is against both self-interest and regard for others. Aristotle Tocqueville’s “Self-interest rightly understood” High Altruism Kant Low Egoism Not beneficial either to self or others Drug addiction Alcoholism, etc. 160 Self-interest and regard for others converge Self-sacrificing altruism High Egoism Self-interest at the expense of others Low Altruism Hobbes’s State of Nature, Nietzsche? Sinking Titanic: Egoism vs. Altruism (Even risks in technical systems) 161 Moral Reasoning and Gender The Kohlberg-Gilligan Debate and Beyond 162 Le Deuxième Sexe - The Second Sex Simone de Beauvoir 1949 Woman as the Other “For a long time I have hesitated to write a book on woman. The subject is irritating, especially to women; and it is not new. Enough ink has been spilled in quarrelling …” Simone de Beauvoir 163 http://www.philosophypages.com/ph/beav.htm Lawrence Kohlberg American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg (Harvard) studied under Swiss psychologist and philosopher Jean Piaget (1965), who had developmental approach to learning. Kohlberg extended the approach to stages of moral reasoning. Using surveys, Kohlberg presented his subjects with moral dilemmas and asked them to evaluate the moral conflict. He was able to prove that youth at various ages, as youth proceed to adulthood, they are able to progress up the moral development stages presented, 164 Lawrence Kohlberg (1927 - 1987) Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development LEVEL STAGE 1 Obedience and Punishment 2 Individualism, Instrumentalism, and Exchange 3 "Good boy/girl" 4 Law and Order 5 Social Contract 6 Principled Conscience Pre-conventional Conventional Post-conventional 165 SOCIAL ORIENTATION Gender and Kohlberg’s scale Women are more likely to base their explanations for moral dilemmas on concepts such as caring and personal relationships. These concepts are likely to be scored at the stage three level. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to base their decisions for moral dilemmas on social contract or justice and equity. Those concepts are likely to be scored at stage five or six. 166 Carol Gilligan University Professor of Gender Studies, Harvard University (1997present) In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development, book 1982. Carol Gilligan, 1936 - present 167 How do we understand Gilligan’s claims? Plato: Meno SOCRATES: (…) By the gods, Meno, be generous, and tell me what you say that virtue is; (…) MENO: (…) Let us take first the virtue of a man--he should know how to administer the state, and in the administration of it to benefit his friends and harm his enemies; and he must also be careful not to suffer harm himself. A woman's virtue, if you wish to know about that, may also be easily described: her duty is to order her house, and keep what is indoors, and obey her husband. Every age, every condition of life, young or old, male or female, bond or free, has a different virtue (…) 168 How do we understand Gilligan’s claims? With the advent of industrial revolution, and welfare state where all children are given education, and physical strength has no dominant role, women have entered the public sphere traditionally dominated by males. Female professionals have encountered a culture that was historically male territory. It caused cultural shock. 169 How do we interpret Gilligan’s claims? Four possible positions about female vs. male moral voices: Separate but equal Superiority thesis Integrationist thesis Diversity thesis 170 The Diversity Thesis Suggests that there are different moral voices Sees this as a source of richness and growth in the moral life External diversity Internal diversity 171 Different individuals have different, sex-based moral voices Males with female voices and females with male voices are admitted Each of us have both masculine and feminine moral voices within us Minimizes gender stereotyping Conclusion “The Show must go on” (Freddy Mercury) Kohlberg – Gilligan controversy is but a beginning of a long process of re-thinking position of women in a postmodern society. The end of industrialist era and the emergency of new information technology results in conditions that even more favor female professionals. 172 ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS 173 The Earth "We have not inherited the Earth from our fathers. We are borrowing it from our children." Native American saying 174 Environmental Ethics and Philosophy Are There Universal Ethical Principles? Universalists: Plato, Kant believe that fundamental principles of ethics are universal, unchanging and eternal Relativists: Sophists- everything contextual. Believe that moral principles are always relative to a particular person Nihilists: Schopenhauer- arbitrary survival. Claim that the world makes no sense at all and that everything is completely arbitrary Utilitarians: Bentham - greatest good for greatest number of people 175 Values, Rights, and Obligations Moral agents. Some philosophers believe that only humans are moral agents Moral subjects. Children are considered moral subjects not moral agents Inherent, instrumental value Non-living things, do they have value? 176 Worldviews and Ethical Perspectives Individual beliefs towards ecology depend on ethical perspectives Most people have set of core values or beliefs Environmental concerns are a source for comparisons among different values and perceptions 177 Worldviews and Ethical Perspectives Domination Interpretation of some religious values has lead in past to anthropocentric (human-centered) ecological principles which believe that humans are the focus of creation Current movement in religious organizations to fight for ecological concerns 178 Worldviews and Ethical Perspectives Stewardship Responsibility to manage our ecosystem. To work together with human and non-human forces to sustain life 179 Worldviews and Ethical Perspectives Biocentrism (life-centered), Animal Rights, and Ecocentrism (ecologically-centered) Biocentrism: biodiversity is the highest ethical value in nature Animal rights supporters focus on the individual Ecocentrism: whole is more important than individual animal Ecofeminism 180 Warren, Shiva, Merchant, Ruether, and King A network of personal relationships Worldviews and ethical perspectives A comparison 181 Philosophy Intrinsic Value Instrumental Value Role of humans Anthropocentric Humans Nature Masters Stewardship Humans & Nature Tools Caretakers Biocentric Species Abiotic nature One of many Animal rights Individuals Processes Equals Ecocentric Processes Individuals Destroyers Ecofeminist Relationships Roles Caregivers Environmental Justice Combination of civil rights and environmental protection that demands a safe, healthy life-giving environment for everyone Most people of low socio-economic position are exposed to high pollution levels 182 Environmental Racism Unequal distribution of hazardous waste based on race Black children 2-3 times more likely to have lead poisoning Dumping Across Borders Toxic colonialism: targeting third/fourth world countries for waste disposal Polluting industries move to poor countries Environmental Justice Act (1992) 183 184 Science as a Way of Knowing A Faustian Bargain? Technology can create power to save and destroy life Dr. Faustus sold his soul to the devil in exchange for power and wealth (youth) 185 Management Theory and the Environment Anthropocentric Theories Ethics Economic Corporate Social Responsibility Stakeholder Normative Social Contract Green Management Theories Ecocentricism Adjusted Stakeholder Sustainablity Resource Based Theory 186 Global Environmental Ethics 187 Environmental Ethics and Business Western Society - Objectifies Nature Locke - “Something in a state of nature has no economic value and is of no utility to the human race” Ethics - a concern with actions and practices directed to improving the welfare of people. 188 Economic Fundamentalism and Ethics The corporate social responsibility of a business is to increase profit. - M. Friedman Those things that cannot be traded on the market have no value. Where does the environment fit in these definitions for environmental ethics? Will people and corporations do environmentally responsible things on their own? What happens if they do? 189 Corporate Social Responsibility By doing socially responsible things, businesses better human life. Hopefully ..good ethics is good business. Is this true? Is enlightened self interest a good way? 190 Incorporating Environment into Management Environmental Ethics is a starting point Expanding ethics to include nature. What is the difficulty in doing this? What does the Biocentric ethic say (Goodpaster?) Biocentrism Natural objects have intrinsic value and morally considerable in their own right. Deep Ecology nature has an ethical status at least equal to humans. 191 Green Management Ecocentrism views industrial relationships in a cycle, and a whole set of philosophies. How radical is this? Sustaincentrism - going beyond sustainability of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Human and economic relationships inextricably linked with natural systems. 192 Resource Extraction and Use Burning of fossil fuels Destruction of tropical rainforests and other biologically rich landscapes Production of toxic wastes 193 Environmental Science Environment - the circumstances and conditions that surround an organism or a group of organisms Environmental science the systematic study of our environment and our place in it 194 What ought I to do? Intention Action Consequence Duty Deontological Ethics 195 What ought I to do? Intention Action Consequence Consequentialist Ethics 196 http://www.envirolink.org/ - Agriculture - Air Quality - Climate Change - Ecosystems - Energy - Environmental Disasters - Environmental Economics - Environmental Education - Environmental Ethics - Environmental Legislation and Policy - Ground Pollution - Habitat Conservation - Human Health - Natural History - Oceans - Outdoor Recreation - Population - Sustainable Business - Sustainable Development - Sustainable Living - Transportation - Urban Issues - Vegetarianism - Waste Management - Water Quality - Wildlife 197 Ethics Contexts Industry (Other firms) Clients Consumers Profession (Societies) Engineering firm Family (Private Sphere) Engineer Colleagues Managers Global environment Society/Nature 198 Research Ethics Committee University of Mälardalen Ethics committee decision making Research ethical issues of MDH, advisory committee: http://www.mdh.se/university/organization/boards/Ethics Decision-making (policy-making) body in Uppsala http://www.epn.se/ 199 What is Professional Ethics? There are many ways to introduce applied/professional ethics with different focus: Pragmatic Embedded Theoretical Emerging Issues 200 Approach 1 Pragmatic Ethical issues are introduced via a consideration of their practical consequences. Consequences are defined in relation to: • The framework of rules and procedures defined by regulatory bodies charged with the task of raising or maintaining professional standards. • Research Ethics Committees and the factors that influence their deliberations 201 Approach 2 Embedded Ethical concerns are presented holistically, as an integral part of some broader area of concern such as: • Fitness for Practice. • Professionalism. The embedded approach places an emphasis on the sense of professional identity. 202 Approach 3 Theoretical This approach focuses on the understanding of ethics theory. The ethics of life-like situations are presented in terms of the application of different ethical theories. 203 Emerging Professional Issues Professional ethics introduces new issues and concerns by seeking to guide and shape graduate behaviour as a way of meeting public expectations with regard to professional conduct and accountability. 204 Professional Ethics Primary Objectives 1. To help professionals make choices that they can live with, and by reducing the emotional and psychological stress caused by moral indecision and confusion. 2. To ensure that the professional acts in a way that serves the best interests of society in general and their serviceusers in particular. 3. To ensure that the professionals acts in a way that serves the best interests of their chosen profession. 205 CRITICISM OF THE SOURCES Academic Honesty 206 What is cheating? Plagiarizing - copying, paraphrasing and self-plagiarizing Unauthorized co-operation Joyriding or taking advantage Fabrication Un-authorized aids 207 Consequences All suspected cases will be reported to the disciplinary committee The teacher is not allowed to haggle or punish! Warning or suspension from classes IDE practice is a zero tolerance against academic dishonesty 208 Rules ”Individually” means by one single person Be prepared to describe carefully how you solved the 209 assignment The names on the cover are the names of those who made the assignment Use references to everything that is not your own present work! When in doubt – ask teacher Read http://www.mdh.se/ide/utbildning/cheating Concluding Comments 210 Conclusion “The Show must go on” (Freddy Mercury) Complexity of the real world problems – number of processes go on concurrently Ambiguity of theoretical representations and interpretations No absolute truth, but the commitment to the commonly accepted ”good enough” ”reasonably good” solutions 211 World seen in different light What if we could see in any wavelength of the electromagnetic spectrum, from gamma-rays to radio waves? How would the world appear to us? 212 Images of the sun RADIO INFRARED ULTRAVIOLET VISIBLE X-RAY 213 Images of the moon RADIO INFRARED ULTRAVIOLET VISIBLE X-RAY 214 Images of galaxy M81 RADIO INFRARED ULTRAVIOLET VISIBLE X-RAY http://hea-www.harvard.edu/CHAMP/EDUCATION/PUBLIC/multiwavelengthphotos_pics.html 215