Seminar Presentation

Moving America Left and Right: 1945-1990

National Humanities Center

An Online Professional Development Seminar

Designed in collaboration with the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction

Made possible through a grant from the

Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation

Nancy MacLean

National Humanities Center Fellow

2008-09

Professor of History and African

American Studies

Northwestern University

Freedom is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace

(2006)

Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan

(1994)

Current Research Interests

The Women’s Movement

The Conservative Movement

School Vouchers

Session I

The Long Black Freedom Movement

Focus Questions

What resources did civil rights organizers have by 1960s that they lacked earlier in U.S. history?

How did the civil rights movement succeed in changing

American culture and institutions?

Where and when did it fall short of its goals? How can we explain the different outcomes?

From Jacqueline Dowd Hall, “The Long Civil

Rights Movement”

“[T]he dominant narrative of the civil rights movement . . . distorts and suppresses as much as it reveals.... [The result is that] it prevents one of the most remarkable mass movements in American history from speaking effectively to the challenges of our time. [That is why we need to learn about and to teach] ... the story of a ‘long civil rights movement’ that took root in the liberal and radical milieu of the late 1930s, was intimately tied to the

‘rise and fall of the New Deal order,’ accelerated during

World War II, stretched beyond the South, was continuously and ferociously contested, and in the 1960s and 1970s inspired a ‘movement of movements’ that def[ies] any narrative of collapse.”

A. Philip Randolph, President, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Broadside for the original March on Washington

These women protesters at the 1963 March on Washington forthrightly issued demands that had a long history in the civil rights movement: decent housing, equal rights, voting rights, and jobs for all.

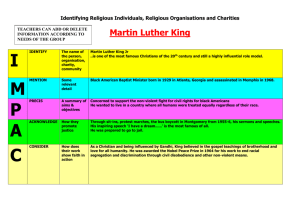

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Where Do We Go from Here?”

(1967)

“With all the struggle and all the achievements, we must fact the fact, however, that the Negro still lives in the basement of the Great Society. He is still at the bottom, despite the few who have penetrated to slightly higher levels. . . . Negroes are still impoverished aliens in an affluent society. They are too poor. . . too impoverished by the ages to be able to ascend by using their own resources. And the Negro did not do this to himself; it was done to him.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Where Do We Go from Here?” (1967)

“I want to say to you as I move to my conclusion, as we talk about ‘Where do we go from here?’ that we must honestly face the fact that the movement must address itself to the question of restructuring the whole of American society. . . . I'm not talking about communism. What I'm talking about is far beyond communism . . . . communism forgets that life is individual.

(Yes) Capitalism forgets that life is social. (Yes, Go ahead) And the kingdom of brotherhood is found neither in the thesis of communism nor the antithesis of capitalism, but in a higher synthesis . . . . it means ultimately coming to see that the problem of racism, the problem of economic exploitation, and the problem of war are all tied together. (All right) These are the triple evils that are interrelated. . . . What I'm saying today is that we must go from this convention and say, ‘America, you must be born again!" [applause] (Oh yes)’

Cesar Chavez, “Letter from Delano,” Good Friday 1969

“Dear Mr. Barr [President, California Grape and Tree Fruit League]:

Today on Good Friday 1969 we remember the life and the sacrifice of Martin Luther King, Jr.,who gave himself totally to the nonviolent struggle for peace and justice…. We are men and women who have suffered and endured much, and not only because of our abject poverty but because we have been kept poor. The colors of our skins, the languages of our cultural and native origins, the lack of formal education, the exclusion from the democratic process, the numbers of our men slain in recent wars –all these burdens generation after generation have sought to demoralize us, to break our human spirit. But God knows that we are not beasts of burden, agricultural implements, or rented slaves; we are men…. And this struggle itself gives meaning to our life and ennobles our dying. . . .

[We] shall overcome . . . by a determined nonviolent struggle carried on by those masses of farm workers who intend to be free and human.

Sincerely yours,

Cesar E. Chavez

United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, A.F.L.-C.I.O.

Delano, CA

Session II

The Long Women’s Movement

Focus Questions

How did feminists, initially a small minority of the population, win changes so quickly in the late 1960s and early 1970s?

Where did the women’s movement fall short of its goals? How can we explain the different outcomes?

In what ways were the women’s movement’s dynamics and goals similar to those of the civil right’s movement? How did they differ?

Bettye Lane, 1970

Nancy MacLean, “Introduction,” The

American Women’s Movement

“The cause that became front page news in the late

1960s had been underway for well over a century. Its potential to become a mass, effective movement grew from the reform infrastructure built during the

Progressive Era and the New Deal period; the demand for a larger and more skilled labor pool generated by

World War II, the cold war, and the postwar consumer economy; and the inspiration and training provided by the labor movement, the civil rights movement, and the

New Left of the 1950s and 1960s. These influences enabled an initially small group to find ways to move hundreds of thousands and to effect significant change.”

From Congress of American Women, “The Position of the American Woman Today” (1946)

“Until the day when the American woman is free to develop her mind and abilities to their fullest extent, without discrimination because of her sex, is free to work without neglecting her children, to live with her husband on an equal level, with adequate provision made for the care of that home without injury to her health; until she takes her full responsibilities as citizen and individual, supporting herself if necessary and her family where she has a family, at a decent wage, paid equally with men for the work she does; until she is freed from the terror of war, and lives in a world of peaceful friendship between nations, in a society without prejudice against Negro,

Jew, [or] national groups of women –her long struggle for emancipation must continue.”

Pauli Murray (1910-1985), who grew up in Durham, N.C., in the 1940s

North Carolina-born Pauli Murray, 1964

“The human rights ‘revolution’ transcends the issue of discrimination on the basis of race or color. Women rights are part of human rights. . . . Negro women especially need protection against discrimination because an even greater percentage of Negro women are heads of families.”

Addie Wyatt addressing a Women’s Affairs Conference of the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA)

Betye Saar

Liberation of Aunt Jemima

Mixed media assemblage

1972

Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, 1995

“We, the Governments participating in the Fourth World

Conference on Women. . . recognize that the status of women has advanced in some important respects in the last decade but that progress has been uneven... [and] also recognize that this situation is exacerbated by the increasing poverty that is affecting the lives of the majority of the world’s people, in particular women and children. . . . We are convinced that . . . women’s equality and their full participation on the basis of equality in all spheres of society. . . are fundamental to the achievement of equality, development, and peace[.] Women’s rights are human rights.”