harm

advertisement

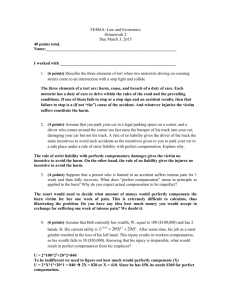

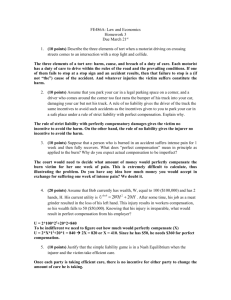

Econ 522

Economics of Law

Dan Quint

Fall 2015

Lecture 15

Reminders

HW3 due next Thursday (November 12) at midnight

Second midterm Wednesday November 18 in class

1

Let’s recap our

story so far…

2

Our story so far

Efficiency

Maximizing total surplus realized by everyone in society

Scarce resources are owned by whoever values them most

(net of externalities, if any)

Actions are taken if social benefit exceeds social cost

Design a legal system that leads to efficient outcomes

Once we set up the rules, we don’t expect people to act based on

what’s efficient

We expect people to do whatever’s in their own best interest

So the goal is set up the rules such that people acting in their

own best interest will naturally lead to efficiency

3

Our story so far

Coase gives us one way to do that

If property rights are clearly defined and tradable, and there are

no transaction costs, people have incentive to trade until each

resource is efficiently owned

So initial allocation of rights doesn’t matter for efficiency

But if there are transaction costs, we may not get efficiency this way

4

Our story so far

Coase gives us one way to do that

If property rights are clearly defined and tradable, and there are

no transaction costs, people have incentive to trade until each

resource is efficiently owned

So initial allocation of rights doesn’t matter for efficiency

But if there are transaction costs, we may not get efficiency this way

Led us to two normative views of the legal system:

1. Minimize transaction costs (“lubricate” private exchange)

2. Allocate rights as efficiently as possible

Tradeoff between injunctive relief and damages

5

Our story so far

Property law works well for simultaneous trade

Contracts allow for non-simultaneous trade

Contract law can…

Enable cooperation

Encourage efficient disclosure of information

Secure optimal commitment to performance

Secure efficient reliance

Supply efficient default rules and regulations

Foster enduring relationships

6

Our story so far

So far, we’ve been talking about voluntary exchange

Coase is predicated on exchange being voluntary for both parties

Contracts are an extension of voluntary trade

Up next: “involuntary trade”

You’re bicycling to class, I’m texting while driving and I hit you

You didn’t want to deal with me, I didn’t want to deal with you…

7

Our story so far

To put it another way…

Property law covers situations where transaction costs are

low enough to get agreement ahead of time

Exceptions to property law – private necessity, eminent domain –

when this isn’t the case

Contract law covers situations when transaction costs are

low enough for us to agree to a contract, high enough that

we may not want to renegotiate the contract later

Tort law covers situations where transaction costs are too

high to agree to anything in advance

8

Tort law

9

An example

10

An example

punish the choice

• criminal law

• regulations

Choice

+

Bad Luck

Outcome

11

An example

punish the choice

punish the outcome

• criminal law

• “strict liability”

• regulations

Choice

+

Bad Luck

Outcome

punish the combination of choice and outcome

• “negligence”

12

Tort law

Tort, noun. from French word meaning injury

Contract law: situations where someone harms you by

breaking a promise they had made

Tort law: situations where someone harms you without

having made any promises

“If someone shoots you, you call a cop. If he runs his car

into yours, you call a lawyer.”

13

As always, we’ll be focused on achieving

efficiency

I hit you with my car, do $1,000 worth of damage

You’re $1,000 worse off

(No damage to me or my car)

Should I have to pay you damages?

I owe nothing

I owe $1,000

I owe $50,000

–1,000

0

49,000

My payoff

0

–1,000

–50,000

Combined

payoffs

–1,000

–1,000

–1,000

Your payoff

14

Something to remember

distribution

but not

efficiency

efficiency

15

Tort law

Question: how to structure the law to get people to behave

in a way that leads to efficient outcomes?

Deliberate harms: make punishment severe (criminal law)

Accidental harms: trickier

Goal isn’t “no accidents”; goal is “efficient number of accidents”

16

Tort law

Question: how to structure the law to get people to behave

in a way that leads to efficient outcomes?

Deliberate harms: make punishment severe (criminal law)

Accidental harms: trickier

Goal isn’t “no accidents”; goal is “efficient number of accidents”

Unlike nuisance law, injunctive relief is not an option

Unlike contract law, no agreement ahead of time

Cooter and Ulen: essence of tort law is “the attempt to make

injurers internalize the externalities they cause, in situations

where transaction costs are too high to do this through

property or contract rights”

17

Cast of characters

Plaintiff – person who brings a lawsuit

Defendant – person who is being sued

In a nuisance case, the defendant caused a nuisance, plaintiff was

bothered by it, might be asking for injunction or damages

In a contract case, defendant breached a contract or violated its

terms

In a tort case, defendant caused some harm to plaintiff, plaintiff is

asking for damages

Plaintiff is the victim (person who was harmed)

Defendant is the injurer (person who caused the harm)

18

“Classic” legal theory of torts

Harm

Causation

Breach of Duty

19

Element 1: Harm

For a tort to exist, the plaintiff needs to have been

harmed

“Without harm, there is no tort”

Gas company sold gas with a defective additive

Dangerous for cars with turbocharged carburetors

You have a car with normal carburetors

You might be angry; but you weren’t harmed, so you can’t sue

Similarly, no compensation for exposure to risk

Manufacturer exposed workers to some chemical

Exposure will cause 15% of them to develop cancer later in life

Can’t sue now – have to wait, see who gets cancer, then they can sue

20

Element 1: Harm

Money

Health

Perfect compensation

restores victim to original level of well-being

generally done through money damages

21

Perfect Compensation

Tangible harms

• Medical costs

• Lost income

• Damaged property

Intangible harms

• Emotional harm

• Pain and suffering

• Loss of companionship

In theory, perfect compensation should cover all losses

Historically, courts have been less willing to compensate for intangible or

hard-to-measure losses

Over time, U.S. courts have started compensating for more intangible harms

22

Perfect Compensation

Tangible harms

• Medical costs

• Lost income

• Damaged property

Intangible harms

• Emotional harm

• Pain and suffering

• Loss of companionship

In theory, perfect compensation should cover all losses

Historically, courts have been less willing to compensate for intangible or

hard-to-measure losses

Over time, U.S. courts have started compensating for more intangible harms

Pro: the closer liability is to actual harm done, the better the incentive to

avoid these harms

Con: disparity in award sizes, unpredictability

23

“Classic” legal theory of torts

Harm

Causation

Breach of Duty

24

Element 2: Causation

For a tort to exist, the defendant needs to have caused the

harm to the plaintiff

Cause-in-fact

“But for the defendant’s actions, would the harm have occurred?”

25

Element 2: Causation

For a tort to exist, the defendant needs to have caused the

harm to the plaintiff

Cause-in-fact

“But for the defendant’s actions, would the harm have occurred?”

26

Element 2: Causation

For a tort to exist, the defendant needs to have caused the

harm to the plaintiff

Cause-in-fact

“But for the defendant’s actions, would the harm have occurred?”

Proximate cause

Immediate cause – defendant’s action can’t be too distant from the

harm

Palsgraf v Long Island Railway (NY Ct Appeals, 1928):

Guard pushed a passenger to help him onto train, passenger dropped

fireworks he was carrying, they went off, explosion knocked down

scales at the other end of the platform, which fell on Mrs. Palsgraf

Guard’s actions were not the proximate cause

27

Element 2: Causation

“A tree fell on a moving trolly, injuring passengers. One of them

sued.

He succeeded in demonstrating that in order for the trolly to be

where it was when the tree fell on it the driver had to have driven

faster than the speed limit at some point during the trip.

Breaking the law is per se negligence, so the driver was legally

negligent whether or not his driving was actually unsafe.

If he had not driven over the speed limit, the trolly would not

have been under the tree when it fell, so, the plaintiff argued, the

driver’s negligence caused the injury.”

Court ruled driver’s negligence “had not caused the accident in

the legally relevant sense”

28

“Classic” legal theory of torts

Harm

Causation

Breach of Duty

29

Element 3: Breach of Duty

(Sometimes required, sometimes not)

Strict Liability

Negligence

• Harm

• Causation

30

Element 3: Breach of Duty

(Sometimes required, sometimes not)

Strict Liability

• Harm

• Causation

Negligence

• Harm

• Causation

• Breach of duty (fault)

When someone breaches a duty he owes to the

defendant, and this leads to the harm, the injurer is

at fault, or negligent

Injurers owe victims the duty of due care

Negligence rule: I’m only liable if I failed to take the required

standard of care – not if I was careful and the accident happened

anyway

31

Hence the language in the trolly example

“A tree fell on a moving trolly, injuring passengers. One of them

sued.

He succeeded in demonstrating that in order for the trolly to be

where it was when the tree fell on it the driver had to have driven

faster than the speed limit at some point during the trip.

Breaking the law is per se negligence, so the driver was

legally negligent whether or not his driving was actually unsafe.

If he had not driven over the speed limit, the trolly would not

have been under the tree when it fell, so, the plaintiff argued,

the driver’s negligence caused the injury.”

32

So under a negligence rule…

If I breach my duty of due care and injure you, I am liable

If I exercise the appropriate level of care but still injure

you, I’m not liable

How is the standard of care determined?

That is, how careful do I have to be to avoid liability, and who

decides?

Is it negligent to drive 40 MPH on a particular road at a particular

time of day? What about 41 MPH? 42?

33

How is the standard of care determined?

Some settings: government imposes safety regulations

that are also used as standard for negligence

Speed limits for highway driving

Requirement that bicycles have brakes

Workplace regulations

Some standards are left vague

“Reckless driving” may depend on road, time of day, weather…

Common law focuses on duty of reasonable care

Level of care a reasonable person would have taken

(Civil law relies less on “reasonableness” tests, tries to spell out

what level of care is required)

34

Strict liability versus negligence

Strict liability rule: plaintiff must prove harm and

causation

Negligence rule: must prove harm, causation, and

negligence

A little history

Early Europe: strict liability was usual rule

By early 1900s, negligence became usual rule

Second half of 1900s, strict liability became more common again,

especially for manufacturer liability in American consumer products

U.S. manufacturers now held liable for harms caused by defective

products, whether or not they were at fault

35

“Classic” legal theory of torts

Harm

Causation

Breach of Duty

36

Next question

Like with contract law, our main concern is with the

incentives created by liability rules

So… what incentives are we interested in?

37

Precaution

38

Precaution

The more carefully I drive, the less likely I am to hit you

But, driving more carefully is also more costly to me

Must be some efficient level of care

Similarly…

Construction company can reduce accidents with better safety

equipment, better training, short workdays, all of which cost money

Manufacturer can reduce accidents by designing/inspecting

products more carefully – again, more expensive

39

Actions by both injurer and victim impact

number of accidents

• speed like hell

• drive slowly

• drive drunk while texting

• drive carefully

• cheap, hasty manufacturing

• careful quality control

• save money

• install smoke detectors, other

safety equipment

• wear helmet and use light

• bicycle at night wearing black

LESS EFFORT TO

PREVENT ACCIDENTS

“LESS PRECAUTION”

GREATER EFFORT TO

PREVENT ACCIDENTS

“MORE PRECAUTION”

40

We will call all these things precaution

Precaution: anything either injurer or victim could do to

reduce likelihood of an accident (or damage done)

The next two questions should be obvious…

How much precaution do we want?

What is efficient level of precaution?

How do we design the law to get it?

41

Simple economic model

for thinking about tort law

42

To answer these questions, we’ll introduce a

very simple model of accidents

Car hits a bicycle

In real life: driver probably has insurance

In real life: some damage to bicycle, some damage to driver’s car

In real life: driver and bicyclist may not even know what the law is

We’ll simplify things a lot, by assuming…

Only one party is harmed

Parties know the law, don’t have insurance (for now)

We’ll focus on one party’s precaution at a time

43

Model of unilateral harm

x

w

p(x)

A

level of precaution

marginal cost of precaution

probability of an accident

cost of an accident

Unilateral harm – just one victim

Precaution – costly actions that make accident less likely

Could be taken by either victim or injurer

We’ll consider both, but one at a time

Notation

x – the amount of precaution that is taken

w – the cost of each “unit” of precaution

p(x) – probability of an accident, given precaution x

so total cost of precaution is wx

p is decreasing in x

A – cost of accident (to victim)

so expected cost of accidents is p(x) A

44

Model of unilateral harm

x

w

p(x)

A

level of precaution

marginal cost of precaution

probability of an accident

cost of an accident

efficient precaution: minx { wx + p(x) A }

$

w + p’(x) A

marginal

social cost

of precaution

w

marginal social

benefit of

precaution

=

0

=

– p’(x) A

wx + p(x) A

(Total Social Cost)

wx (Cost of Precaution)

p(x) A (Cost of Accidents)

x* (Efficient Level

of Precaution)

x < x*

x > x*

Precaution (x)

45

A technical note (clarification)

We’re thinking of bilateral precaution, just “one at a time”

So really, xinjurer, xvictim, problem is

minxi, xv { p(xi, xv) A – wi xi – wv xv }

“Hold fixed” one party’s action and consider the other:

minxi { p(xi, xv) A – wi xi – wv xv } given xv (and v.v.)

This has same solution as

minxi { p(xi, xv) A – wi xi }

Our result will generally be “efficient given what the other

guy is doing”

46

Effect of liability rules on precaution

We know what’s efficient

Level of precaution that minimizes total social cost = wx + p(x) A

We’ll consider what happens if there is…

no liability rule in place

a strict liability rule

a negligence rule

47

Benchmark: what happens

without any liability rule?

Skip

48

Benchmark: No Liability

In a world with no liability…

Injurer does not have to pay for accidents

So, bears cost of any precautions he takes, but does not receive

any benefit

Injurer has no incentive to take precaution

Victim bears cost of any accidents, plus cost of precaution he takes

(Victim precaution imposes no externality on injurer)

Victim precaution will be efficient

49

Benchmark: No Liability

$

Injurer’s private cost

is just wx

Private cost to injurer

Private cost to victim

Minimized at x = 0

Victim’s private cost

is p(x) A + wx

wx + p(x) A

wx

Minimized at efficient

precaution level x = x*

p(x) A

x*

x

So rule of no liability leads to efficient precaution by

victims, no precaution by injurers

50

Benchmark: No Liability

No Liability

Injurer

Precaution

Victim

Precaution

Zero

Efficient

51

Precaution isn’t the only thing that

determines number of accidents

Precaution – actions which make an activity less dangerous

Driving carefully

Wearing bright-colored clothing while bicycling

The amount we do each activity also affects the number of

accidents

I decide how much to drive

You decide how much to bicycle

Liability rules create incentives for activity levels as well as

precaution

52

With no liability rule…

With no liability, I’m not responsible if I hit you

I don’t consider cost of accidents when deciding how fast to

drive…

…and I also don’t consider cost of accidents when deciding

deciding how much to drive

So I drive too recklessly, and I drive too much

(or: if there is no liability, social cost of driving includes cost of

accidents, but private cost to me does not;

driving imposes negative externality, so I do it too much)

So with no liability, injurer’s activity level is inefficiently high

53

What about victims?

With no liability, victim bears full cost of accidents

Greater activity by victim (more bike-riding) leads to more accidents

Victim weighs cost of accidents when deciding how carefully to ride,

and when deciding how much to ride

(Private cost = social cost)

Victim takes efficient level of precaution, and efficient level of

activity

A rule of no liability leads to an inefficiently high level of

injurer activity, but the efficient level of victim activity

54

Benchmark: No Liability

No Liability

Injurer

Precaution

Victim

Precaution

Injurer

Activity

Victim

Activity

Zero

Efficient

Too High

Efficient

55

Next up:

Strict Liability

and Negligence

56