Kubrick's SF - The Homepage of Dr. David Lavery

advertisement

Special Topics in

Film Studies: The

Films of Stanley

Kubrick

Dr. David Lavery

Fall 2012

1964

The Making of Dr.

Strangelove

A Documentary

Chapter Titles (as listed on the DVD)

Dr. Strangelove

1. Start

2. Condition Red

3. Wing Attack Plan R

4. Fred Calls Buck

5. Three Simple Rules

6. Attack Profile

7. Captain Mandrake

8. In the War Room

9. Six Points

10. Survival Kit Check

11. Ambassador De Sadesky

12. Friendly Fire

13. Merkin and Dimitri

14. A Monstrous Commie Plot

15. Dr. Strangelove

16. Ripper’s Theory

17. The Base Surrenders

18. Evasive Action

19. Colonel “Bat” Guano

20. Assessing the Damage

21. Deviated pervert

22. One Plane Left

23. A Change of Target

24. “Is There Really a Chance?”

25. Final Check”

26. “Yahoo!!!”

27. 100-Year Plan

28. “We’ll Meet Again”

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and

Love the Bomb

UK (1964): Science Fiction/Comedy/War

93 min, No rating, Black & White

Production Credits

Producer: Stanley Kubrick

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenwriter: Stanley Kubrick, Terry Southern, Peter

George, based on the novel Red Alert by George

Cinematographer: Gilbert Taylor

Editor: Anthony Harvey

Composer: Laurie Johnson

Production designer: Ken Adam

Art director: Peter Murton

Special effects: Wally Veevers

Costumes: Bridget Sellers

Makeup: Stuart Freeborn

Cast List

Peter Sellers: Capt. Lionel Mandrake/President Merkin

Muffley/Dr. Strangelove

George C. Scott: Gen. "Buck" Turgidson

Sterling Hayden: Gen. Jack D. Ripper

Keenan Wynn: Col. "Bat" Guano

Slim Pickens: Maj. T.J. "King" Kong

Peter Bull: Ambassador de Sadesky

Tracy Reed: Miss Scott

James Earl Jones: Lt. Lothar Zogg

Jack Creley: Mr. Staines

Frank Berry: Lt. H.R. Dietrich

Glenn Beck: Lt. W.D. Kivel

Shane Rimmer: Capt. G.A. "Ace" Owens

Paul Tamarin: Lt. B. Goldberg

Gordon Tanner: Gen. Faceman

Robert O'Neil: Adm. Randolph

Roy Stephens: Frank

xxxxx

MAD: Mutually

Assured

Destruction

Watch the whole film online here.

50 Years Ago This Month: The

Cuban Missile Crisis, October

1962

November-December 1963

November 22nd: President Kennedy

assassinated.

November 23rd: First episode of Doctor

Who airs.

December 12th: Scheduled premiere of

Doctor Strangelove scheduled but

cancelled.

Dr. Strangelove, 93 minutes

A Dr. Strangelove Lexicon

merkin: a genital

hairpiece or toupee

A Dr. Strangelove Lexicon

turgid(son): swollen ,

engorged, tumescent

General Buck Turgidson

A Dr. Strangelove Lexicon

(Bat) guano: A substance

composed chiefly of the dung of sea birds

or bats, accumulated along certain coastal

areas or in caves and used as fertilizer.

Colonel “Bat”

Guano

A Dr. Strangelove Lexicon

mandrake:

A southern European

plant (Mandragora officinarum) having

greenish-yellow flowers and a branched root.

This plant was once believed to have magical

powers because its root resembles the human

body.

Group Captain Lionel

Mandrake

In 1960 the novelist Philip Roth

predicted that by the 21st century

the front page of the New York

Times would be satire.

Black Humor

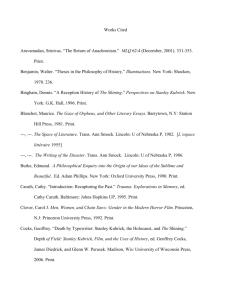

From Murfin, Ross and Supryia M. Ray. The Bedford Glossary of Critical

and Literary Terms. Boston: Bedford 1997.

black humor: A dark, disturbing, and often morbid or grotesque mode of

comedy found in certain modern texts, especially antinovels and Absurdist

works. Such humor often concerns death, suffering, or other anxiety-inducing

subjects. Black humor usually goes hand in hand with a pessimistic world-view or

tone; it manages to express a sense of hopelessness in a wry, sardonic way that

is grimly humorous.

EXAMPLES:

Thomas Pynchon's V (1963), Joseph , Heller's Catch-22 (1961), and John

Kennedy Toole's novel A Confederacy of Dunces (1980) contain a great deal of

black humor. Little Shop of Horrors, originally a Roger Corman film that was

made into a long-running musical and then remade as a movie (1986), contains

many instances of black humor. Other contemporary films utilizing black humor

include Eating Raoul (1982) and Fargo (1996). The writer and illustrator Edward

Gorey consistently incorporates black humor into children's books; in The

Gashly'crumb Times (1962), Gorey presents each letter of the alphabet via the

name of a child who met an untimely death: "A is for Amy, who fell down the

stairs. B is for Basil, assaulted by bears...."

Black Humor

From the Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (2003)

[I]n literature, drama, and film, grotesque or morbid humor used to express the

absurdity, insensitivity, paradox, and cruelty of the modern world. Ordinary

characters or situations are usually exaggerated far beyond the limits of normal

satire or irony. Black humor uses devices often associated with tragedy and is

sometimes equated with tragic farce. For example, Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr.

Strangelove; or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1963) is a

terrifying comic treatment of the circumstances surrounding the dropping of an

atom bomb, while Jules Feiffer’s comedy Little Murders (1965) is a delineation of

the horrors of modern urban life, focusing particularly on random assassinations.

The novels of such writers as Kurt Vonnegut, Thomas Pynchon, John Barth,

Joseph Heller, and Philip Roth contain elements of black humor.

Black Humor

From Cuddon, J. A. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory.

Fourth Edition. NY: Penguin, 1998.

BLACK COMEDY. The term is a translation of comedie noire, which we owe to

Jean Anouilh (1910-88), who divided his plays of the 1930S and 1940s into pieces

roses and pieces noires. It is more than likely that the term also in part derives

from Andre Breton's Anthologie de I'humeur noire (1940), which is concerned

with the humorous treatment of the shocking, horrific and macabre. Black

comedy is a form of drama which displays a marked disillusionment and

cynicism. It shows human beings without convictions and "with little hope,

regulated by fate or fortune or incomprehensible powers. In fact, human beings

in an 'absurd' predicament. At its darkest such comedy is pervaded by a kind of

sour despair: we can't do anything so we may as well laugh. The wit is mordant

and the humour sardonic.

This form of drama has no easily perceptible ancestry, unless it be tragi-comedy

(q.v.) and the so-called 'dark' comedies of Shakespeare (for instance. The

Merchant of Venice, Measure for Measure, All's Well that Ends Well and The

Winter's Tale). However, some of the earlier works of Jean Anouilh (the pieces

Black Humor

noires) are blackly comic: for example, Voyageur sans ba.ga.ge (1936) and La.

Sauvage (1938). Later he wrote what he described as pieces grincantes

(grinding, abrasive), of which two notable examples are La Valse des toreadors

(1952) and Pauvre Bitos (1956). Both these plays could be classified as black

comedy. So might two early dramatic works by Jean Genet: Les Bonnes (1947)

and Les Negres (1959). Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962),

Pinter's The Homecoming (1965) and Joe Orton's Loot (1965) are other examples

of this kind of play. The television dramatist Giles Cooper also made a very

considerable contribution.

In other forms of literature 'black comedy' and 'black humour' (e.g. the 'sick

joke') have become more and more noticeable in the 20th c. It has been

remarked that such comedy is particularly prominent in the so-called 'literature

of the absurd'. Literary historians have found intimations of a new vision of man's

role and position in the universe in, for instance, Kafka's stories (e.g. The Trial, The

Castle, Metamorphosis), in surrealistic art and poetry and, later, in the philosophy

of existentialism {q.v.). Camus's vision of man as an 'irremediable exile', lonesco's

concept of life as a 'tragic farce', and Samuel Beckett's tragi-comic characters

Black Humor

in his novels are other instances of a particular Weltanschauung (q.v.).

A baleful, even, at times, a 'sick' view of existence, alleviated by

sardonic (and, not infrequently, compassionate) humour is to be found

in many works of 2oth c. fiction; in Sartre's novels, in Genet's nondramatic works also, in Giinter Grass's novels, in the more apocalyptic

works of Kurt Vonnegut (junior). One might also mention some less

famous books of unusual merit which are darkly comic. For example,

Serge Godefroy's Les Loques (1964), Thomas Pynchon's V (1963) and his

The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), Joseph Heller's Catch-22 (1961), D. D. Bell's

Dicky, or The Midnight Ride of Dicky Vere (1970) and Mordecai Richler's

St Urbain's-Horseman (1966). See NONSENSE; SURREALISM; THEATRE OF

CRUELTY; THEATRE OF THE ABSURD.

Stills from the Set of Dr. Strangelove

Stills from the Set of Dr. Strangelove

Stills from the Set of Dr. Strangelove

Stills from the Set of Dr. Strangelove

John Hall Wheelock

Earth

"A planet doesn’t explode of itself," said drily

The Martian astronomer, gazing off into the air.

"That they were able to do it is proof that highly

Intelligent beings must have been living there."

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Kubrick’s shock upon learning

about the first atomic bomb

test (about the possible chain

reaction that might result).

Kubrick claimed he

considered moving to

Australia to avoid nuclear war.

The “people will laugh”

concern.

Discovered Terry Southern via

The Magic Christian (given to

him by Peter Sellers).

Scott claimed he deserved

screen credit.

Sellers came up with the idea

that his hand was still a Nazi.

15 weeks of principal

photography.

Terry Southern

(1924-1995)

Terry Southern Official Site

Perspectives in American

Literature on Southern

Internet Movie Data Base Page

Terry Southern, "Notes from the

War Room"

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Shepperton Studios outside of

London—13,000 square feet.

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Sellers was originally to play Kong but was

reluctant. Southern helped with the accent, but

after falling on the bomber set, Sellers opted out.

John Wayne was offered the role of Kong, and

Dan Blocker was considered, but rejected it as

“too pinko.” Kubrick remembered Slim Pickens

from the One-Eyed Jacks project.

Sellers might have played “Buck Schmuck” as

well.

Sellers paid

$1,000,000—50%

of the entire

budget.

Kubrick spotted

James Earl

Jones on stage

and cast him as

Lt. Lothan Zogg.

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Hayden had trouble with the technical jargon but

found Kubrick very understanding.

Reliance on Jane’s.

Often contrasted to Fail-Safe (Sidney Lumet, 1964)

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Names in earlier versions: Admiral Buldike, Private

Tung, Major Nonce, Lt. Binky Ballmuff.

Always eating—according to Jones.

Composer Laurie [a man) Johnson built the score

around “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.”

Was Columbia’s biggest success of 1964.

The pie fight that was cut.

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986.

DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB

(BRITISH/I 964) B&W/93m-102m. Stanley Kubrick directed this classic nightmare

comedy, which he, Terry Southern, and Peter George adapted from George's

more serious novel Red Alert. It's so funny because, as ludicrous as the characters

and events are, there is nothing in this picture that is beyond the realm of

possibility. Perhaps we are laughing at ourselves (instead of worrying) for living in a

world whose fate is controlled by buffoons. One buffoon is General Jack D. Ripper

(Sterling Hayden). Believing that the communists have poisoned the water supply—

that, he believes, is why his sexual proficiency has diminished—he orders U.S.

bombers to conduct a nuclear attack on Russia. He kills himself rather than reveal

the recall code to his British assistant, Capt. Lionel Mandrake (Peter Sellers).

President Muffley (also Sellers) explains the situation to the Soviet Premier (we never

see him), who informs Muffley that if a nuclear bomb goes off in Russia then a

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic

Russian Doomsday device will destroy the world. Perverse Dr. Strangelove (Sellers

again), a former Nazi who works for the U.S., reveals his contingency plan in which

America's politicians, top brass, and bigwigs will retreat to underground chambers

where there will be ten women for every man. Kubrick considered ending the film

with a slapstick pie fight in the war room. I'm glad he didn't. Watching the film

today, I grow impatient with most of the scenes outside the war room. Inside there

are many classic bits: gum chewing Gen. Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott)

explaining to Muffley what Ripper has done; Muffley having hilarious Bob Newharttype conversations over the hot line; Strangelove (who's not in the film enough)

trying to stop his out-of-control metal hand (which automatically gives a Nazi

salute) from strangling him. Sellers is marvelous in all three roles (he has a terrific

American accent) —somehow he lost out on the Oscar, which went to Rex

Harrison for My Fair Lady. Photography is by Gilbert Taylor. Production design is by

Ken Adam. Vera Lynn's WWII recording of "We'll Meet Again" is used effectively at

the conclusion. Also with: Keenan Wynn, Slim Pickens (who rides a bomb to cinema

glory), Peter Bull, Tracy Reed, James Earl Jones.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review: 3.5 stars out of 5

More relevant with each passing year, Stanley Kubrick's uproariously funny yet

deadly serious DR. STRANGELOVE did much to bring underground filmmaking

techniques and concerns into the commercial mainstream. Combining a

satirical indictment of U.S./U.S.S.R. Cold War policies, brilliantly limned

caricatures, and an inventive visual style, this extraordinary black comedy, like

Stanley Kubrick's masterful 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968), makes an important

statement about the apocalyptic consequences of humankind's relinquishment

of its destiny to machines.

Synopsis. Mad bomber. After opening with the midair refueling of a long-range

bomber, the film shifts into high gear when Gen. Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden)

goes completely mad, seals off Burpelson Air Force Base, and sends his bomber

wing to attack the Soviet Union. U.S. President Merkin J. Muffley (Peter Sellers, in

one of three roles he performs) responds by calling a desperate meeting with his

advisors, including blustery Gen."Buck" Turgidson (George C. Scott) and Dr.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Strangelove (Sellers again), a mysterious, wheelchair-bound German scientist

whose mechanical arm is always on the verge of launching his black-gloved

hand into a Nazi salute. After a hot-line consultation with the Soviet leader,

Premier Kissoff who is finally tracked down at a Moscow brothel, drunk, a plan is

formulated to shoot down the American planes. Although the Soviets have been

informed of every U.S. move, they remain suspicious and set into motion their

dreaded "Doomsday Machine"—a defensive system with a destructive capacity

so great that the world will be engulfed in fallout for more than ninety years

should even one bomb be dropped on the USSR and automatically trigger the

buried nuclear weapons.

Back at Burpelson, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (once more Sellers), a British

liaison officer, busies himself with trying to trick Gen. Ripper into revealing the

code that will recall his bombers. He is unsuccessful, however, as the mad

general—who is convinced that the fluoridation of water is a communist plot—

puts him off with tales of how he has kept his "precious bodily fluids" to himself,

"denying women [his] essence." Gen. Ripper then excuses himself, goes into a

washroom, and blows out his brains.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Code busting. Meanwhile, a force commanded by Col. "Bat" Guano (Keenan

Wynn) breaks through Ripper's defenses just as Mandrake has determined the

recall code. With only a pay phone to alert the White House but without a dime,

Mandrake suggests they break into a soda pop vending machine. Col. Guano,

who warns the Briton against trying any "preeversions," shoots into the machine,

but not before warning Mandrake that he will have to answer to the Coca-Cola

Company of America.

Armed with the code, President Muffley's War Room staff is able to recall all of

the bombers that haven't been shot down except the one piloted by crafty Maj.

T.J. "King" Kong (Slim Pickens), who guides his damaged plane through the Soviet

defenses on its way to a secondary target. As the plane approaches its

objective, however, trouble arises with the bomb release mechanism. Ever the

enterprising warrior, Maj. Kong manually releases the bomb, and, cowboy hat in

hand, rides it to earth like a bronco buster.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Doomsday. The explosion, of course, triggers the Russian "Doomsday Machine."

Just before the end of the world, President Muffley and Dr. Strangelove fritter

away precious time discussing how society's male elite and a proportionately

larger contingent of beautiful women might survive the nuclear holocaust in

underground hideouts, eventually repopulating the planet. Then, moments

before the screen is filled with mushroom clouds and the sound track swirls with

Vera Lynn's version of "We'll Meet Again," Dr. Strangelove staggers to his feet,

proclaiming, "Mein Fuhrer, I can walk."

Critique. One of the finest, funniest, most intelligent black comedies ever made,

DR. STRANGELOVE demonstrates Kubrick's mastery of cinematic art from its first

frame to its last. The film is more than just funny or didactic, however, becoming

engrossingly suspenseful as Kubrick continually shifts his focus from one of the

film's three principal settings to another, cutting among them with increasing

rapidity as the film nears its climax, catching the audience up inextricably in the

tension-filled race to save the world.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Expressive set design. Moreover, each of the film's relatively inexpensive sets is

skillfully designed and photographed to heighten the impact of the events that

transpire there. As production designer Ken Adam explained to Michael Ciment,

author of Stanley Kubrick, the War Room was rendered larger than life to lend

the distanced decision-making that occurs there an appropriately fantastic

quality. Gen. Ripper's office and Kaj. Kong's bomber, The Leper Colony, on the

other hand, are presented with a gritty realism. Indeed, the scenes inside the

bomber are claustrophobically framed and filmed with source lighting, while the

assault on the Air Force base—shot in a cinéma vérité style with a hand-held

camera that was operated most of the time by Kubrick himself—has the look of

a documentary. In each case the results are among the 1960s' most expressive

black-and-white images.

Sexual imagery. Throughout the film Kubrick also uses his visuals to suggest the

connection between the warring impulse and the male sex drive. From the

sensual quality of the midair refueling that opens the film to Maj. Kong's

wahooing ride to destruction on the huge oblong bomb at the film's end, DR.

STRANGELOVE is full of phallic and sexual imagery. All of it mirrors the sexual

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

obsessions of the film's most militant warriors: Jack Ripper's hoarding of his

precious bodily fluids and Buck Turgidson's profligacy with his, most notably with

his secretary, Miss Scott (Tracy Reed), who also appears as the centerfold in the

Playboy ogled by Maj. Kong.

Comedy started as drama. Significantly, Kubrick intended his adaptation of

Peter George's novel Red Alert to be a straightforward drama, along the lines of

FAIL-SAFE, 1964's other cautionary tale about the horrors of nuclear weaponry.

However, as Gene D. Phillips notes in Stanley Kubrick: A Film Odyssey, Kubrick

decided to make the film "a nightmare comedy" after discovering, while trying

to flesh out the screenplay, that he was continually forced to leave out things

"which were either absurd or paradoxical in order to keep [the screenplay] from

being funny; and these things seemed to be close to the heart of the scenes in

question." Collaborating with George and Terry Southern, Kubrick crafted an

immensely clever script, loaded with hilariously memorable scenes and

dialogue, enlivened by the improvisational contributions of the film's

accomplished cast.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Cast. At the time of the film's release, none of the cast members had attained real

star status (though Sellers and Scott would later, of course). Rather, Kubrick

assembled an extraordinarily talented lineup of character actors and let them run

with their roles. Scott is unforgettable as gut-slapping hawk Buck Turgidson (the film's

character names are themselves a howl). His War Room scuffle with Soviet

Ambassador de Sadesky—played with terrific tongue-in-cheek stoicism by Peter

Bull—is among the film's highlights, topped off by Muffley's killer punch line:

"Gentleman, you can't fight in here. This is the War Room!" Equally delightful is Scott's

bug-eyed description of a lone bomber's chances against the Soviet defenses.

But as good as Scott's performance is, Sellers steals the show, bringing deft comic

shading to each of his three roles: milquetoast liberal President Muffley; reserved but

exasperated Group Captain Mandrake (whose slow burns bring to mind those of

Monty Python's Cleese); and the absurdly grinning Dr. Strangelove, whose battles

with his arm with an ideology of its own are worth the price of admission as he

whips, bangs, and even sits on it before his hand finally attempts to strangle him.

Hayden, Pickens, Wynn, and, in a smaller role, James Earl Jones also contribute

wonderfully over-the-top supporting performances.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Surprisingly, Kubrick originally intended to end DR. STRANGELOVE with a colossal

custard pie fight in the War Room. In fact, he spent nearly a week filming the

melee before opting to culminate the film with a bang and sneer—the ironic

combination of exploding hydrogen bombs and "We'll Meet Again."

Certainly Stanley Kubrick is one of the masters of the American cinema, his

impressive oeuvre including such outstanding films as THE KILLING (1956); PATHS

OF GLORY (1957); SPARTACUS (1960); LOLITA (1962); 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

(1968); A CLOCKWORK ORANGE (1971); BARRY LYNDON (1975); THE SHINING

(1980); and FULL METAL JACKET (1987).

Awards. Sellers was nominated for the Best Actor Oscar, as well as Kubrick for

Best Direction and the film itself for Best Picture, but all lost to MY FAIR LADY.

Kubrick, Peter George and Terry Southern were also nominated for Best Adapted

Screenplay.

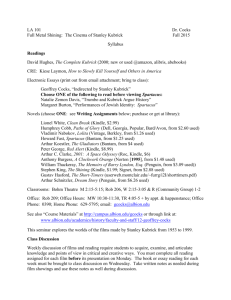

Special Topics in

Film Studies: The

Films of Stanley

Kubrick

Dr. David Lavery

Fall 2012

1968

"[Like the monolith in 2001, Stanley

Kubrick] was a force of supernatural

intelligence, appearing at great

intervals amid high-pitched shrieks,

who gives the world a violent kick up

the next rung of the evolutionary

ladder."

David Denby

Chapter Titles (as listed on the DVD)

2001: A Space Odyssey

1. Overture

2. Opening Credits

3. The Dawn of Man

4. From Earth to the Moon

5. Voice Print Identification

6. Squirt

7. A Great Big Mystery

8. Off to Clavius

9. Purpose of the Visit

10. Deliberately Buried

11. The Monolith

12. Jupiter Mission

13. The World Tonight

14. Frank’s Parents

15. Chess with HAL

16. Sketches and Suspicions

17. Removing the AE35

18. Human Error?

19. A Bad Feeling

20. Intermission

21. Cut Adrift

22. Rescue Mission

23. The Big Sleep

24. “Open the Doors!”

25. Emergency Airlock

26. My Mind is Going

27. Prerecorded Briefing

28. Jupiter

29. . . . And Beyond the Infinite

30. Through Space and Time

31. Star Child

32. End Credits

2001: A Space Odyssey

UK (1968): Science Fiction

Production Credits

139 min, Rated PG, Color, Available on videocassette and laserdisc

Producer | Stanley Kubrick

Director | Stanley Kubrick

Screenwriter | Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, based on the short story

"The Sentinel" by Clarke

Cinematographer | Geoffrey Unsworth, John Alcott

Editor | Ray Lovejoy

Production designer | Tony Masters, Harry Lange, | Ernest Archer

Art director | John Hoesli

Special effects | Stanley Kubrick, Wally Veevers, Douglas Trumbull

Costumes | Hardy Amies

Makeup | Stuart Freeborn

2001: A Space Odyssey

UK (1968): Science Fiction

Cast List

Keir Dullea | David Bowman

Gary Lockwood | Frank Poole

William Sylvester | Dr. Heywood Floyd

Daniel Richter | Moonwatcher

Leonard Rossiter | Smyslov

Margaret Tyzack | Elena

Robert Beatty | Halvorsen

Sean Sullivan | Michaels

Frank Miller | Mission Controller

Alan Gifford | Poole's Father

Vivian Kubrick | | "Squirt"

John Ashley | Astronaut

Dave: Open the pod bay doors, please, HAL. Open the pod bay doors,

please, HAL. Hello, HAL. Do you read me? Hello, HAL. Do you read me?

Do you read me, HAL?

HAL: Affirmative, Dave. I read you.

Dave: Open the pod bay doors, HAL.

HAL: I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that.

Dave: F&*K you HAL!

HAL: Without your space helmet, Dave, you're going to find that rather

difficult.

--Found on the door of a toilet stall, St. Cloud State University, St. Cloud,

Minnesota, 1972

W. R. Robinson on 2001:

(with Mary McDermott), “2001 and the Literary

Sensibility”

“The Birth of Imaginative Man in Part III of 2001: A

Space Odyssey”

David Lavery, “Like

Light: The Movie Theory

of W. R. Robinson”

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review: 3.5 stars out of 5

A beautiful, confounding picture that had half the audience cheering and the

other half snoring. Stanley Kubrick clearly means to say something about the

dehumanizing effects of technology, but exactly what is hard to say. One of

those works presumed to be profound by virtue of its incomprehensibility, 2001 is

nevertheless an astounding visual experience—one to be enjoyed, if possible,

only on the big screen.

Synopsis

The distant past. The story can be synopsized, but can it be understood? For the

first half hour or so, we are treated to the sight and grunts of a tribe of apes, circa

4 million years ago. Kubrick uses actors in ape suits plus a few real animals, and

they happily cavort as vegetarians in their prehistoric world. Then a large black

monolith appears and seems to be calling to the apes. The moment they touch

the ebony slab, the peaceful simians become carnivorous, territorial, and begin

using the bones of their prey as weapons to keep other apes away from their

small domain. A bone is tossed in the air, begins to revolve in slow motion, and

the film jumps 4 million years forward to 2001.

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

At the lunar station. The rotating bone becomes the rotating spaceship Orion. Dr.

Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) is a scientist aboard the spaceship on his way

to a lunar station. When he is questioned by Russian colleagues about why they

have been banned from the space station despite having an agreement with

the U.S., Dr. Floyd says he has no idea why they are not allowed. He arrives at the

station and talks to several Americans. It turns out he knows full well why the

Russians have been kept in the dark, but he has been forbidden to speak of it to

anyone other than people cleared on the highest classified level.

Discovery. There has been a tremendous discovery, and the U.S. government

fears that any leak of the "discovery" might cause a panic back on Earth. Dr.

Floyd and his compatriots use a lunar buggy to go to the site and come upon

the monolith that is, as near as they can determine, 4 million years old. They

approach the edifice, which lets out an ear-piercing screech that seems to be in

the direction of Jupiter.

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Meet HAL. Dissolve to a year-and-a-half later, as a spaceship makes its way to Jupiter.

David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) run the ship with the

help of HAL 9000, the most sophisticated computer ever devised. The voice of HAL

(Douglas Rain) has a pleasant tone but with the slightest malevolent edge. (Martin

Balsam had originally recorded the voice but was replaced.) There are three other

men in a deep freeze, and neither Poole nor Bowman knows the real mission. HAL

knows, but he has been programmed not to tell them until they reach their

destination. Poole and Bowman take care of the minor business aboard the ship,

exercise, and try to keep from going nuts as HAL runs the voyage.

HAL takes over. The computer is not supposed to ever tell a lie or make an error, so

they take it as Gospel when HAL says there is a malfunction in the spaceship's

antenna. They plan to go outside and do an on-site check. On Earth, the men at

mission control report that HAL is wrong and that it is impossible for such a thing to

have happened. Poole and Bowman wonder now about the efficacy of their onboard computer. Poole goes outside the spaceship, and HAL arranges to have the

lifeline cut. Poole is floating in space, and Bowman attempts to rescue him but fails.

At the same time, HAL shuts off the units that are keeping the deep-frozen astronauts

alive.

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Bowman tries to get back on board but is being stopped by the machinations of

HAL. He finally gets back on the ship by manually overriding the computer. Once

on board, Bowman cuts off the electrical system that keeps HAL going and now

learns about the slab found on the moon. The ship approaches Jupiter, and

Bowman sees a slab go past his ship. The next sequence has Bowman immersed

in a light show, a vast array of many-colored oceans and seas and skies and

explosions, none of which he can fathom (and all of which were sheer delight to

the drug-laden viewers of the late 1960s, who thought this movie was heavensent).

Next thing he knows, he is in a bedroom circa 1700, where he discovers an old

man, himself at age 100. Bowman plays both characters, who have an enigmatic

conversation. Then a monolith appears in the room and moves toward the bed.

Finally, an embryo that looks vaguely like Bowman is seen floating toward Earth

as the film concludes.

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Critique

For sheer spectacle, it may be unsurpassed; for storytelling, it stays as dark and

deep as the monolith that is its focal point. Kubrick was delighted by the

confusion the movie caused and maintained that he deliberately kept questions

unanswered because he wanted to pique the curiosity of audiences. The rebirth

of Bowman at the film's end has been thought to signify the next leap forward of

humankind, but that is still open for discussion. Some have said that it broke new

ground by creating a new film "language." We think that a bit more story would

have helped, or at least a translation of this new language. 2001 continues to

annoy and delight audiences years later, and its real meaning cannot be

explained to anyone's liking.

The casting of Lockwood, Dullea, and Sylvester, three undynamic actors (in these

roles), must have been deliberate, as Kubrick didn't want anything in the way of

his vision (whatever that was).

The movie has many Woody Allen-like jibes at Howard Johnson's, Hilton Hotels,

and others.

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Clarke's short story was first made into a novel, then into the screenplay that

MGM financed for $6 million. The budget kept rising, and the studio execs feared

a disaster. They didn't reckon with Kubrick's vision. Made at a cost of only $10.5

million, the film began to build slowly but eventually took in almost $15 million in

North America, then about half that upon rerelease in the slightly shorter version

(141 minutes) in 1972.

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY was followed by a sequel in 1984, 2010.

Awards

Understandably, the movie won the Oscar for Best Special Effects in 1968, and

was nominated for Best Direction, Best Screenplay, and Best Art Direction. It also

took the BFA Awards for Best Cinematography, Best Sound, and Best Art

Direction.

2001: A Space Odyssey

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review

Music

Made at Boreham Richard Wood's British Studios in England, it featured many

classical tunes as the background score: Aram Khatchaturian's "Gayane Ballet

Suite" (played by the Leningrad Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Gennadi

Rozhdestvensky), Richard Strauss's "Thus Spake Zarathustra" (played by the Berlin

Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Karl Boehm), Johann Strauss's "Blue Danube

Waltz" (played by the Berlin Symphony, conducted by Herbert von Karajan),

Gyorgy Ligeti's "Atmospheres" (played by the Southwest German Radio

Orchestra, conducted by Ernst Baur), Ligeti's "Lux Aeterna" (played by the

Stuttgart State Orchestra, conducted by Clytus Gottwald), and Ligeti's "Requiem

for Soprano, Mezzo-Soprano, Two Mixed Choirs and Orchestra" (played by the

Bavarian Radio Orchestra, conducted by Francis Travis).

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic. New York: Simon and

Schuster, 1986.

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (BRITISH/I 968) C/ 141m-160m. The most

awesome, beautiful (the visuals and classical music), mentally

stimulating, and controversial science-fiction film ever made was

directed by Stanley Kubrick, adapted from Arthur C. Clarke's short story

"The Sentinel" by Kubrick and Clarke, and photographed by Geoffrey

Unsworth and John Alcott, and features incredible, Oscar-winning

special effects by Wally Veerers, Douglas Trumbull (who supervised the

miraculous star-gate sequence). Con Pederson, and Tom Howard. It

begins four million years ago when a black monolithic slab appears to a

family of apes. Once peaceful vegetarians, they become meat-eaters

and intelligent enough to use bones as weapons to kill other animals for

food and to chase other apes away from their territory. They have

evolved into apemen and their human descendants will retain their

warring instincts—progress and brutality go hand in hand—the territorial

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

imperative, and a notion of God. It is for the viewer to decide if the

superior alien intelligence that sent the monolith and caused man to

evolve from the apes (instead of the neighboring tapirs!) is God as we

define God. (I believe that Kubrick thinks the concept of God is so

unfathomable to us that if an alien intelligence has the power over us

that we always associated with God, then we might as well call it God.)

Film moves from the past to 2001, when Dr. Heywood Floyd (William

Sylvester), an American scientist, investigates the discovery of a

monolith on the moon. The monolith sends a piercing signal (through

space's vacuum?), a distant intelligence, no doubt, that man has

evolved to the point where the monolith has been discovered. But man

is nothing special: he is boring, untrusting (Floyd keeps the discovery

secret from the Russians), nationalistic, uncommunicative; while man

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

has made great technical advances in communication, men are

incapable of meaningful, intelligent conversation, and are unworthy of

their own scientific achievements. American big business has

expanded: Pan Am, Bell Telephone, the Hilton chain, and Howard

lohnson's are prominent at the space station. On a spaceship we see

that the astronauts. Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Poole (Gary Lockwood),

are completely subservient to a computer named HAL. HAL is actually

more interesting than the men—they are mechanized; HAL is a neurotic.

HAL represents both a Frankenstein monster turning on its human

creators (he tries to dispose of the crew) and a Big Brother in which,

unlike the situation in Orwell, men intentionally have set up to spy on

them. There is no scarier scene than when HAL reads the lips of Bowman

and Poole as they plan to dismantle this rebellious computer. In an

unforgettable scene Bowman dismantles HAL. The battle between man

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

and computer, resulting in HAL'S death, releases emotions that Bowman had

previously held in check: fear and sorrow. The destruction of the oppressive

computer is the signal to the aliens—who may have set up the combat, if

we are to believe the dualist concept of God's omnipotence and man's

having free will under God's auspices—that Bowman is worthy of being the

human being who comes to them. After traveling through space—"the

ultimate trip"—Bowman finds himself in a terrarium observed by alien

creatures. There he ages rapidly and becomes the first character in the film

to eat at a table and the first to eat tasty food—from a plate, too. He

becomes civilized man; Kubrick believes that "the missing link between the

apes and civilized man is the human being—us." Lastly, Bowman dies and

evolves into a star child, floating through space toward earth. The evolution

of man from ape to angel is complete. Originally released in Cinerama at

160m. Peter Hyams directed the badly muddled, forgettable 2070. Also with:

Daniel Richter, Leonard Rossiter, Margaret Tyzack, Douglas Rain (voice of

HAL).

The Music of 2001

The Blue Danube by Johann Strauss

The Music of 2001

“Thus Spake Zarathustra” by Richard Strauss

The Music of 2001

Atmosphères by György Ligeti

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Working Titles: How the Solar System Was Won, Universe,

Tunnel to the Stars, Planetfall, Journey Beyond the Stars

Kubrick admired Forbidden Planet (Fred M. Wilcox, 1956).

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Kubrick sought out Clarke, whose Childhood’s End he

admired greatly

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008).

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Kubrick was worried about “outguessing the future.”

Concerned about the ending.

Budget of $10.5 million.

The moon based was built at Shepperton.

Kubrick didn’t like filming further than 10 miles from home.

“The Dawn of Man” used second unit work in Namibia.

The crotch problem.

The centrifugal cylinder

The role of Douglas Trumbull.

The Stargate sequence and Jordon Belson (1926-2011). (The

image below is from Allures (1961).

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

No name cast.

Bland, inane dialogue.

HAL (and IBM).

Rejecting North’s score. Last minute choices.

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

The bone to spaceship match cut.

Special Topics in

Film Studies: The

Films of Stanley

Kubrick

Dr. David Lavery

Fall 2012

1971

Production Credits

137 min, Rated R, Color, Available on

videocassette and laserdisc

Producer: Stanley Kubrick

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenwriter: Stanley Kubrick, based on

the novel by Anthony Burgess

Cinematographer: John Alcott

Editor: Bill Butler (cinematographer)

Composer: Walter Carlos

Production designer: John Barry

Art director: Russell Hagg, Peter Shields

Stunts: Roy Scammell

Costumes: Milena Canonero

Makeup: Freddie Williamson, George

Partleton, Barbara Daly

Chapter Titles (as listed on the DVD)

1. Alex and His Droogs

2. The Old Ultraviolence on a Tramp

3. Battling Billy Boy

4. Through the Real Country Dark

5. Country House

6. Disciplining Dim

7. At Home with Ludwig Von

8. Home Ill; Mr. Deltoid

9. The Music Shop

10.Two Ladies

11. Dissent Among Droogs

12.A Real Leader

13.The Cat Lady’s House

14.Now a Murderer

15.Prisoner #655321

16. The Chaplain’s Remarks

17. Big Book Fantasies

18. The Minister’s Visit

We will watch all the chapters in

bold.

19. Arrival at Ludovico

20.“And Vidi Films I Would”

21. “I’m Cured, Praise God!”

22. On Display

23. The Sickness

24. Your True Believer

25. Family Reunion

26.No Room for Alex

27. Three Familiar Faces

28. Droogs with Badges

Break

29. Return to the Country House

30. Mr. Alexander’s Hospitality

31. The Hospital

32. A Slide Show

33. A Very Special Visitor

34.“I Was Cured All Right”

35. End Credits

Lindsay Anderson

(1923-1994)

Six Degrees of

Separation (me,

Clockwork)

Lindsay Anderson (1923-1994)

Six Degrees of Separation (me,

Clockwork)

1973

1968

Six Degrees of

Separation (me,

Clockwork)

Six Degrees of

Separation (me,

Clockwork)

Clockwork as a Cult Film

Eco, Umberto. "Casablanca:

Cult Movies and Intertextual

Collage." Travels in Hyper

Reality. Trans. William

Weaver. New York:

Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich,

1986: 197-211.

LIVING TEXTUALITY. The authentic cult work,

Eco observes, must seem like "living textuality,"

as if it had no authors, as postmodernist proof

that "as literature comes from literature,

cinema comes from cinema" (199).

Clockwork as a Cult Film

A COMPLETELY FURNISHED WORLD. Another

closely related prerequisite of The Cult, Eco

observes, is its capacity to "provide a

completely furnished world so that its fans can

quote characters and episodes as if they were

aspects of the fan's private sectarian world, a

world about which one can make up quizzes

and play trivia games so that the adepts of the

secret recognize through each other a shared

experience" (198).

Clockwork as a Cult Film

DETACHABILITY. The cult work, according to Eco,

must also be susceptible to breaking, dislocation,

unhinging, "so that one can remember only parts of

it, irrespective of their original relationship with the

whole." The cult viewer watching these moments-indeed watching for such moments—may let out an

audible "I love this."

Clockwork as a Cult Film

Anthony

Burgess

(1917-1993)

Cast List

Malcolm McDowell: Alex

Patrick Magee: Mr. Alexander

Michael Bates: Chief Guard

Warren Clarke: Dim

John Clive: Stage Actor

Adrienne Corri: Mrs. Alexander

Carl Duering: Dr. Brodsky

Paul Farrell: Hobo

Clive Francis: Lodger

Michael Gover: Prison Warden

Miriam Karlin: Cat Lady

James Marcus: Georgie

Aubrey Morris: Deltoid

Godfrey Quigley: Prison Chaplain

Sheila Raynor: Mum

Madge Ryan: Dr. Branom

John Savident: Conspirator Dolin

Anthony Sharp: Minister of Interior

Philip Stone: Dad

Pauline Taylor: Psychiatrist

Margaret Tyzack: Conspirator Rubinstein

Steven Berkoff: Constable

Lindsay Campbell: Inspector

Michael Tarn: Pete

David Prowse: Julian

Jan Adair: Handmaiden

Prudence Drage: Handmaiden

Vivienne Chandler: Handmaiden

John J. Carney: C.I.D. Official

Richard Connaught: Billyboy

Carol Drinkwater: Nurse Feeley

George O'Gorman: Bootick Clerk

Cheryl Grunwald: Rape Victim

Gillian Hills: Sonietta

Craig Hunter: Dr. Friendly

Barbara Scott: Marty

Virginia Wetherell: Stage Actress

Katya Wyeth: Girl in Fantasy

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE (originally

prepared by Stanley Edgar Hyman). Words that

don't seem to be of Russian origin are distinguished

by asterisks.

*appy polly loggy—apology

baboochka—old woman

baddiwad—bad

banda—band

bezoomny—mad

biblio—library

bitva—battle

Bog—God

bolnoy—sick

bolshy—big, great

brat, bratty—brother

bratchny—bastard

britva—razor

brooko—belly

brosay—to throw

bugatty—rich

cal—feces

*cancer—cigarette

cantora—office

carman—pocket

chai—tea

*charles, charlie—chaplain

chasha—cup

chasso—guard

cheena—woman

cheest—to wash

chelloveck—person, man, follow

chepooka—nonsense

choodessny—wonderful

*chumble—to mumble

clop—beak

collocoll—bell

*crack—to break up or "bust"

*crark—to yowl?

crast—to rob or steal; robbery

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

creech—to shout or scream

*cutter—money

dama—lady

ded—old man

deng—money

devotchka—girl

dobby—good

*dook—trace, ghost

domy—house

dorogoy—dear, valuable

dratsing—fighting

*drencrom—drug

droog—friend (ie: my droogies)

*dung—to defecate

dva—two

eegra—game

eemya—name

*eggiweg—egg

*filly—to play or fool with

*firegold—drink

*fist—to punch

*flip—wild?

forella—"trout"

gazetta—newspaper

glazz—eye

gloopy—stupid

*golly—unit of money

goloss—voice

goober—lip

gooly—to walk

gorlo—throat

govorett—to speak or talk

grahzny—dirty

grazzy—soiled

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

gromky—loud

groody—breast

gruppa—group

*guff—guffaw

gulliver—head

*gulliwuts—guts

*hen-korm—chickenfeed

*horn—to cry out

horrorshow—good, well

*in-out in-out—copulation

interessovat—to interest

itty—to go

*jammiwam—jam

jeezny—life

kartoffel—potato

keeshkas—guts

kleb—bread

kootch—key

knopka—button

kopat—to "dig"

koshka—cat

kot—tomcat

krovvy—blood

kupet—to buy

lapa—paw

lewdies—people

*lighter—crone?

litso—face

lomtick—piece, bit

loveted—caught

lubbilubbing—making love

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

*luscious glory—hair

malchick—boy

malenky—little, tiny

maslo—butter

merzky—filthy

messel—thought, fancy

mesto—place

millicent—policeman

minoota—minute

molodoy—young

moloko—milk

moodge—man

morder—snout

*mounch—snack

mozg—brain

nachinat—to begin

nadmenny—arrogant

nadsat—teenage

nagoy—naked

*nazz—fool

neezhnies—underpants

nochy—night

noga—foot, leg

nozh—knife

nuking—smelling

oddy knocky—lonesome

odin—one

okno—window

oobivat—to kill

ookadeet—to leave

ooko—ear

oomny—brainy

oozhassny—terrible

oozy—chain

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

osoosh—to wipe

otchkies—eyeglasses

*pan-handle—erection

*pee and em—parents

peet—to drink

pischcha—food

platch—to cry

platties—clothes

pletcho—shoulder

plenny—prisoner

plesk—splash

*plosh—to splash

plott—body

podooshka—pillow

pol—sex

polezny—useful

*polyclef—skeleton key

pony—to understand

poogly—frightened

pooshka—"cannon"

prestoopnik—criminal

privodeet—to lead somewhere

*pretty polly—money

prod—to produce

ptitsa—"chick"

pyahnitsa—drunk

rabbit—work, job

radosty—joy

raskazz—story

rassoodock—mind

raz—time

razdraz—upset

razrez—to rip, ripping

rock, rooker—hand, arm

rot—mouth

rozz—policeman

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

sabog—shoe

sakar—sugar

sammy—generous

*sarky—sarcastic

scotenna—"cow"

shaika—gang

*sharp—female

sharries—buttocks

shest—barrier

*shilarny—concern

*shive—slice

shiyah—neck

shlem—helmet

*shlaga—club

shlapa—hat

shoom—noise

shoot—fool

*sinny—cinema

shazat—to say

*skolliwoll—school

skorry—quick, quickly

*shriking—scratching

shvat—to grab

sladky—sweet

sloochat—to happen

sloosh, slosshy—to hear, to listen

slovo—word

smech—laugh

smot—to look

sneety—dream

*snoutie—tobacco?

*snuff it—to die

sobirat—to pick up

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

*sod—to fornicate, fornicator

soomaka—"bag"

soviet—advice, order

spat—to sleep

spatchka—sleep

*splodge, splosh—splash

*spoogy—terrified

*Staja—State Jail

starry—ancient

strack—horror

*synthemesc—drug

tally—waist

*tashtook—handkerchief

*tass—cup

tolchock—to hit or push;blow,

beating

toofles—slippers

tree—three

vareet—to "cook up"

*vaysay—washroom

veck—(see chelloveck)

*vellocet—drug

veshch—thing

viddy—to see or look

voloss—hair

von—smell

vred—to harm or damage

yahma—hole

*yahoodies—Jews

yabzick—tongue

*yarbles—testicles

yeckate—to drive

*warble—song

GLOSSARY OF NADSAT LANGUAGE

zammechat—remarkable

zasnoot—sleep

zhenna—wife

zoobies—teeth

zvonock—bellpull

zvook—sound

Alex: There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs,

that is Pete, Georgie Boy and Dim. And we sat in the

Korova Milk Bar trying to make up our rassoodocks

what to do with the evening. The Korova Milk Bar sold

milk plus - milk plus vellocet or synthemesc or

drencrom which is what we were drinking. This would

sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of the

old Ultra-Violence.

Clockwork Dialogue

Alex: “Viddy well, little brother, viddy

well!”

Clockwork Dialogue

Alex: I woke up, the pain and sickness all over me like

an animal. Then I realized what it was. The music

coming up from the floor was our old friend Ludwig

Van and the dreaded 9th Symphony. Let me out.

Open the door, open the door. Turn it off, turn it off,

turn it off, turn it off, turn it off. Stop it. Turn it off. Turn it

off. Turn it off. Turn it off. Please, turn it off. Suddenly I

viddied what I had to do and what I had wanted to

do and that was to do myself in. To snuff it, to blast off

forever from this wicked cruel world. One moment of

pain perhaps and then sleep forever and ever.

Clockwork Dialogue

Dim: What did you do that for?

Alex: For being a bastard with no manners. Without a dook of an

idea about how to comport yourself public-wise, O my brother.

Dim: I don't like you should do what you done and I'm not your

brother no more and wouldn't want to be.

Alex: Watch that. Do watch that O Dim, if to continue to be on live

thou dost wish.

Dim: Yarbles, great bouncy yarblockos to you I'll meet you with

chain, or nudge, or britva, any time, I'm not have you aiming

tolchoks at me reasonless. It stands to reason, I won't have it.

Alex: And I'll scrap any time you say.

Dim: Right, right. Doobidoob. A bit tired may be best not to say more.

Bedways is rigthways now, so best we go homeways and get a bit of

spatchka. Right, right.

Clockwork Dialogue

It had been a wonderful evening and what I

needed now to give it the perfect ending was

a bit of the old Ludwig Van. Oh bliss, bliss and

heaven. Oh it was georgeousness and

georgeosity made flesh. It was like a bird of

rarest spun heaven metal, or like silvery wine

flowing in a spaceship gravity all nonsense now

as I slooshied I knew such pretty pictures.

Clockwork Dialogue

Alex: This is the real weepy and tragic part of

the story being O my brothers and only friends.

After a trial with judge and a jury and some

very hard words spoken against your friend

and humble narrator, he was sentenced to

fourteen years in Stargent number 84-F among

smelly perverts and hardened crustoodniks.

Clockwork Dialogue

And viddy films I would. Where I was taken to, Brothers, was like no cine I

ever viddied before. I was bound up in a straight jacket and my guliver

was strapped to a headrest with like wires running away from it. Then

they clamped like lidlocks on my eyes so that I could not shut them no

matter how hard I tried. It seemed a bit crazy to me but I let them get on

with it. If I was to be a free young malchick again in a fortnights time I

would put up with much in the meantime, O my Brothers. So far the first

film, was a very good professional piece of cine. Like it was done in

Hollywood. The sounds were real horroshow, you could slooshie the

screams and moans very realistic. You could even get the heavy

breathing and panting of the tolchcoking malchicks at the same time.

And then what do you know, soon our dear old friend the red red vino on

tap. The same in all places, like it was put out by the same big firm,

began to flow. It was beautiful. It's funny how the colors of the real world

only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen. Now all the

Clockwork Dialogue

time I was watching this, I was beginning to get very aware of like not

feeling all that well. And this this I put down to all the rich food and

vitamins. But I tried to forget this concentrating on the next film which

jumped right away on a young devotchka who was being given the old

in-out, in-out. First by one malchick, then another, then another. When it

came to the sixth or seventh malchick leering and smecking and going

into it, I began to feel really sick. But I could not shut my glassies and even

if I tried to move my glassballs about, I still not get out of the line of fire of

the picture.

Clockwork Dialogue

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic. New York: Simon

and Schuster, 1986.

CLOCKWORK ORANGE, A (British/1971) C/137m. In the not too

distant future our Humble Narrator, young Alex (Malcolm

McDowell), and his pals (“droogs”) spend the nights

practicing ultra-violence: beating, raping, terrorizing citizens.

One night Alex kills a snobbish man, and his droogs, who are

angry with him, knock him out and leave him for police. He's

sent to prison. His only chance for freedom is to undergo the

Liberal Party's experimental "Ludovico" treatment whereby he's

made ill when watching violent movies; afterward violence and

Beethoven make him nauseous. When freed he is unable to hurt

a fly; he becomes the victim of the droogs (now policemen)

and ends up in the house of liberal Mr. Alexander (Patrick

Magee), who doesn't recognize Alex as the one who raped

and caused the death of his wife. Eventually Alex gets that evil

gleam back in his eye. You can't cure the habitual thrill criminal.

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic.

Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of Anthony Burgess's novel is

visually brilliant and thematically reprehensible. Because Alex is

meant to embody our savage, anarchic impulses, Kubrick

figured we'd identify with him. At least, that is what he

intended—so that we wouldn't identify with Alex's victims, he

manipulates us into accepting Alex in relation to the world.

Played by McDowell instead of by a less appealing actor of the

Sean Penn mold, Alex is energetic, handsome, witty, and more

clever, honest, intelligent, aid interesting than any of the adults

in the cruel world. Without exception, Kubrick makes Alex's

victims more obnoxious than they are in the book (his treatment

of women is insulting). Kubrick makes their abuse at Alex's hands

more palatable by making them grotesque, mannered,

snobbish figures. Kubrick uses other distancing devices: extreme

wide angles, slow motion, fast motion, surreal backgrounds,

songs that counterpoint the violence. The violence that Alex

perpetrates is very stylized, but when it comes time for him to

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic.

endure violence (a bottle to the head, police brutality, the

Ludovico technique), it is much more realistic. Poor Alex we

think. Our hostility is directed toward everyone, but he is like an

alley cat who is declawed before being returned to the streets.

Burgess believed that the book and film were parables that

expressed two basic points: "If we are going to love mankind,

we will have to love Alex as a not-unrepresentative member of

it; it is preferable to have a world of violence undertaken in full

awareness—violence chosen as an act of will—than a world

conditioned to be good or harmless." But the mankind Kubrick

shows us is totally alien to us and not worthy of our love. And

even before he undergoes the Ludovico treatment, Alex's

violent acts don't seem to be made through free choice, but

are reflexive, conditioned by past violence—he is already a

clockwork orange (human on the outside, mechanized on the

inside). Film's strong, gratuitous violence is objectionable (as is

the comical atmosphere when violence is being perpetrated)

but the major reason the film can be termed fascistic is Kubrick's

heartless, super-intellectual, super-orderly, antiseptic,

From Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic.

anti-human, anti-female, anti-sensual, anti-passion, anti-erotic

treatment of its subject. In his cold world, all emotional stimuli,

from drugs to Beethoven, are lumped together as being

harmful; all art (classical music, theater, literature, painting,

sculpture, and film) is pornographic. Film has cult following due

to wild clothes, visual design, and violence. John Alcott is the

cinematographer. Also with: Anthony Sharp (as the Minister who

wants to us "cured" Alex for political purposes), Warren Clarke,

Aubrey Morris, James Marcus, Michael Tarn, Adrienne Corri,

Michael Bates

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Was considering Eyes Wide Shut when he decided to do

Clockwork.

Terry Southern once owned the rights.

A producer (Sandy Lieberson) wanted to do it with Mick

Jagger (a big fan) as Alex and the others Stones as his

droogs; Ken Russell considered doing it as well.

Fears of censorship from the beginning.

Abandoned Napoleon to embark on Clockwork.

Kubrick ignored previous screenplays and wrote his own

(using a computer).

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

McDowell’s injuries: near drowning, broken ribs, scratched

corneas, freezing in the shower.

Abuse of Adrienne Corri

McDowell was 28, twice the age of the novel’s Alex.

Prowse [Julian] + James Earl Jones = Darth Vader.

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Walter/Wendy Carlos hired to do electronic versions of Ninth.

Rossini’s William Tell, Purcell’s Music on the Death of Queen

Mary.

“Singin’ in the Rain”: the only song McDowell knew.

“There seems to be an assumption that if you’re offended by movie

brutality, you are somehow playing into the hands of the people who

want censorship. But this would deny those of us who don’t believe in

censorship the use of the only counterbalance: the freedom of the

press to say that there’s anything conceivably damaging in these

films — the freedom to analyze their implications. If we don’t use this

critical freedom, we are implicitly saying that no brutality is too much

for us — that only squares and people who believe in censorship are

concerned with brutality. Actually, those who believe in censorship

are primarily concerned with sex, and they generally worry about

violence only when it’s eroticized. This means that practically no one

raises the issue of the possible cumulative effects of movie brutality.

Yet surely, when night after night atrocities are served up to us as

entertainment, it’s worth some anxiety. We become clockwork

oranges if we accept all this pop culture without asking what’s in it.

How can people go on talking about the dazzling brilliance of movies

and not notice that the directors are sucking up to the thugs in the

audience?”—Pauline Kael

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

Kubrick was vehemently anti-censorship but his “self-imposed

became the most effective censorship of a film in British

history.”

Production budget: $2 million; worldwide gross $15.4 million

Complete Kubrick Talking Points

A Clockwork Orange

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review: 4.0 stars

out of 5

Teenage delinquents Alex (Malcolm McDowell), Dim (Warren Clarke),

Georgie (James Marcus), and Pete (Michael Tarn) living in a futuristic

British state, indulge in nightly rounds of beatings, rapings, and, as they

call it, "ultraviolence." Among their victims is prominent writer Mr.

Alexander (Patrick Magee); they beat him senseless, and brutally gangrape his attractive wife (Adrienne Corri). (Mr. Alexander later becomes

manic, and his wife dies as a result of the attack). After violently quelling

an uprising among his own gang, Alex is betrayed by them during an

attack on another home, having been knocked senseless and left for the

police. In prison, he agrees to undergo experiments in "aversion therapy"

in order to shorten his term. Now nauseated by the mere sight of

violence, he is pronounced cured and released into the outside world.

There, vengeance of one kind or another is wreaked upon him by his

erstwhile fellow gang-members (now policemen), and by his former

victims (including Mr. Alexander). After another spell in prison Alex returns

home, where we expect him to resume his old criminal ways.

A Clockwork Orange

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review: 4.0 stars

out of 5

Critique

Adapted from the novel by British author Anthony Burgess, A

CLOCKWORK ORANGE is a visually dazzling, highly unsettling work that

revolves around one of the few truly amoral characters in either film or

literature. It pits a gleefully vicious individual against a blandly inhuman

state, leaving the viewer little room for emotional involvement (though

McDowell gives such an ebullient, wide-eyed performance as the

Beethoven-loving delinquent that it is hard for us not to feel some

sympathy toward him). Meanwhile, we are dazzled by Stanley Kubrick's

directorial pyrotechnics—slow motion, fast motion, fish-eye lenses, etc.;

entertained by John Barry's witty, ostentatious sets; and intrigued by

dialogue laden with Burgess's specially created slang (gang members

are "droogies," sex is "the old inout," etc.). This is a particularly graphic film

which has divided critics, but which no serious moviegoer can afford to

ignore.

A Clockwork Orange

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review: 4.0 stars

out of 5

Awards

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE won four Academy Award nominations: Best

Picture; Best Director; Best Adapted Screenplay; and Best Editing. The film

was also honored by the New York Film Critics Circle with awards for Best

Picture and Best Director.