6. US chapter 2 Moving toward a Constitution

advertisement

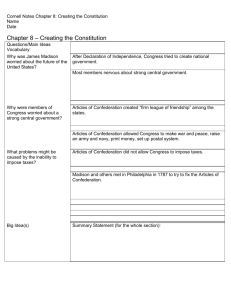

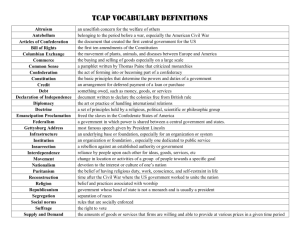

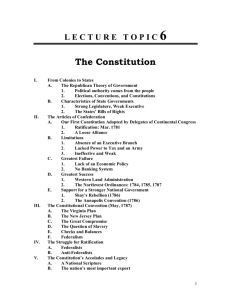

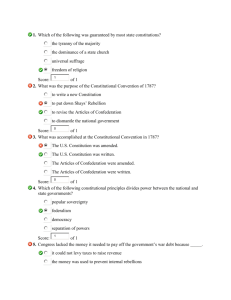

Toward a Constitution Chapter 2 Introduction •The American Revolution led not to general chaos but to a remarkably orderly process of constitution-making. •From the 1760s through the 1780s, there occurred a prolonged debate over the fundamental issues of government. “The Critical Period” (1781-1787) • The years the U.S. operated under the Articles of Confederation • A fear of centralized power dominated the period • Characteristics of state governments: • weak governors • weak judiciary • strong legislature • written constitutions and guaranteed rights The Articles of Confederation • A highly decentralized governmental system in which the national government derives limited authority from the states rather than directly from citizens. • No executive • No judiciary • Congress had a multitude of responsibilities but little authority to carry them out • 13 independent state republics under a nearly powerless national government. Successes of the Confederation •The Temptations of the West •Congress could have an independent income with the sale of land. •Western land cessions, 1781-1802 •Congress had decided to treat as equal states rather than colonies. The Northwest Territory •Land Ordinance of 1785 • A plan of surveys and sales. •Rectangular pattern on much of the nation. •Northwest Ordinance of 1787 •Provided a guideline to achieve statehood. •Excluded slavery from the Northwest. Problems for the Confederation • Wartime economic disruption • Public and private debt • Postwar inflation (currency shortage) • Trade barriers at home and abroad • U.S. had not gained their economic independence • Popular Uprisings • Shay’s Rebellion (1,200 disgruntled farmers who attacked the federal arsenal in Mass. seeking debt and tax relief and a flexible monetary policy) • Major laws required unanimous agreement From Confederation to a New Constitution • Many began demanding revisions to the Articles of Confederation. • On February 21, 1787, the Continental Congress resolved that: • ...it is expedient that on the second Monday in May next a Convention of delegates who shall have been appointed by the several States be held at Philadelphia for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation... The Constitutional Convention • The original states, except Rhode Island, collectively appointed 70 individuals to the Constitutional Convention, but a number did not accept or could not attend. • Those who did not attend included Richard Henry Lee, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Samuel Adams and, John Hancock. • In all, 55 delegates attended the Constitutional Convention sessions, but only 39 actually signed the Constitution. • http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_ freedom/constitution/founding_fathers.html Drafting a New Constitution •Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in May of 1787 •The delegates were able to draw from their Revolutionary War experience. •George Washington was elected to preside over the convention. •James Madison took a seat up front and began recording the debates that would occur. Assembly Room in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, site of the signing of the Constitution in 1787. Getting Down to Business •Most of the delegates at Philadelphia thought that they would resolve commercial conflicts among themselves or amend the Articles of Confederation. •A few, however, were planning (and devising a strategy) to scrap the Articles and start over. •On the first day of substantive business James Madison and his nationalist colleagues sprang their surprise – their blueprint for a new constitution. The Virginia Plan • Shifted focus of deliberation from patching up the confederation to considering what was required to create a national union. • Its centerpiece was a bicameral legislature. • Members of the lower chamber apportioned among the states by population and directly elected. • Lower chamber would elect members of the upper chamber from lists generated by the state legislatures. The Virginia Plan •Also stipulated that the national government could make whatever laws it deemed appropriate and veto any state laws it regarded as unfit. •If a state failed to fulfill its legal obligation, the national government could use military force against it. The Virginia Plan • Many saw this proposed legislature as too powerful. • Opposition grew toward the Virginia plan from two directions: • Less populous state. Why? • States’ rights delegates. Why? The New Jersey Plan •The groups that disagreed with Madison’s proposal coalesced around an alternative proposed by New Jersey delegate William Paterson in response to the Virginia Plan. •It kept the national legislature as it existed under the Articles – each state had equal status regardless of population. The New Jersey Plan •However it did attempt to fix the worst problems of the Articles by giving Congress the authority to levy taxes and to enforce compliance by the state with their obligations •Given its quick creation, it had its own faults: it failed to propose the organization of the executive and judiciary. •Debate continued, however, as neither side was happy with the options given by their opponents for the composition of Congress. The Great Compromise Fashioning the National Legislature • A committee was appointed to come up with a solution to the stalemate. • Each side got one of the two legislative chambers fashioned to its liking. • The upper chamber (Senate) would be composed of two delegates sent from each state legislature who would serve a 6 year term. • Madison’s population-based, elective legislature became the House of Representatives. • The unanimous agreement rule was replaced by a rule allowing a majority of the membership to pass legislation. The Great Compromise The Necessary and Proper Clause • In addition to specifying a broad list of enumerated or expressed powers, the committee proposed a clause that authorized Congress to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States….” The Great Compromise Madison and Checks and Balances • Given the compromise, Madison became interested in a genuine separation of powers between the branches with each side exercising checks and balances over the others. • Played a significant role in Madison’s formulation of the executive and judiciary as independent institutions. Designing the Executive • Preferences ranged from Hamilton’s executive “elected for life” at one end and the existing model of state governors who had been given very limited powers. • At the same time, most agreed that the nation’s first executive would be George Washington. • There was much that had to be debated- in particular, how would the executive be selected. • A compromise led to the convoluted concept of the electoral college. The Electoral College •The electoral college mixes state, congressional, and popular participation in the election process. •Each state is awarded as many electors as it has members of the House and Senate. •The Constitution left it to the states to decide how electors are selected, but the Framers generally expected that the states would rely on statewide elections. •If any candidate fails to receive an absolute majority in the electoral college, the election is thrown into the House of Representatives. Vote by state delegations. An Independent Executive • Madison and Hamilton largely succeeded in fashioning an independent executive by: • Giving the president the ability to veto legislation. • By requiring a supermajority of each house to override a presidential veto. • But the Framers also checked the executive’s power in numerous ways. • See previous chart. Designing the Judiciary • The convention spent comparatively little time designing the new federal judiciary. • They did debate over two questions: • Who would appoint Supreme Court justices? • And should a network of lower federal courts be created or should state courts handle all cases until they reach the federal court? • The extent of the Court’s authority to overturn federal laws and executive actions as unconstitutional – the concept of judicial review – was not resolved at this point. The Issue of Slavery • Slavery was not absent from the debates. It was present at several important junctures. • One critical point was during the creation of the national legislature. • Southern states wanted to count slaves as part of the population thus giving them more representatives in the House. Yet these “citizens” had no rights in that state. • After much debate, the southern states were allowed to count a slave as three-fifths of a person. • A ban on regulation of slavery until 1808. Amending the Constitution •An amendment can be proposed either by: •A two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress. •Or by an “application” from two-thirds of the states. •And an amendment can be enacted when: •Three-fourths of the states (through their legislatures or special conventions) accepts the amendment. The Fight for Ratification • “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of the Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.” • This statement did two important things: • It removed the unanimous assent rule of the Articles of Confederation. • It withdrew authority from the state legislatures, which might have misgivings about surrendering autonomy. The Federalist and Antifederalist Debate • Antifederalists argued against this new form of government. (states’ rights) • Argued that only local democracy could approach true democracy. • Stronger national government must come with safeguards against tyranny. • For this reason, the Bill of Rights was included almost immediately after ratification. The Federalist Argument (the rhetoric of nationalism) • The Federalist Papers • 85 essays (written by Hamilton, Madison, and Jay), which were directed primarily at New York, which had not yet voted in 1788 although by this point the Constitution was technically ratified. • Provided insight into the meaning of the Constitution. Ratification •New Hampshire was the ninth to ratify •June 21, 1788 •Rhode Island held out until 1790