Freedom of Speech - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

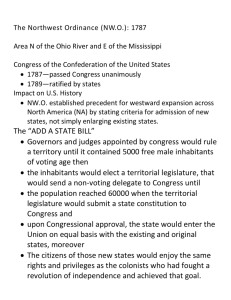

Freedom of Speech Political Speech & Freedom of the Press The Bill of Rights Institute Tribune Tower Chicago, IL, November 7, 2005 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University Political Speech 1st Amendment: “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press. . .” Speech in times of crisis: the 1st Amendment is not absolute. In times of peace there is little reason to restrict expression. In times of crisis (war, economic collapse, natural catastrophes, or internal rebellion) the government places a priority on national unity and takes firm action against subversive groups and opposition criticism—often restricting the right of the people to speak, publish, and organize. Speech in Times of Crisis We will examine free speech law in the following periods of crisis: Revolution (1775-1781) Civil War (1861-1865) WWI (1917-1918) WWII (1941-1945) & the Cold War Vietnam War (1963-1975) War on Terrorism (2001-) The Question Had a crisis not existed, would the Court have decided the case the same way? Our answer to this question should serve as a reminder that Supreme Court justices may be as vulnerable to public pressures and to waves of patriotism as the average citizen. The Revolution & the Founders The Sedition Act of 1798: “Any person [who] shall write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing against the government of the United States, or either House of Congress, or the President, with intent to defame . . . or to bring them into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them the hatred of the good people of the United States . . . shall be punished by a fine not exceeding $2,000, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.” Why did the founders pass such a law? Politics. The Federalist party was losing ground to the AntiFederalist and passed the act to suppress opposition. Jefferson vigorously attacked the law and it expired in 1801 when Jefferson took over the White House and his allies gained control of Congress. President Abraham Lincoln took a number of steps to suppress “treacherous” behavior, believing “that the nation must be able to protect itself in war against utterances which actually cause insubordination.” The Civil War Several times during the war, Lincoln issued orders expanding military control over civilian areas in the North, permitting military arrests and trials of civilians, and suspending habeas corpus. Art. I, Sec. 9 of the Constitution says, “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” The problem was that the suspension provision is found in Art.I, which outlines legislative, not executive power. Also if the civilian courts are in full operation and no armed hostilities are taking place in the area, the public safety probably does not demand a suspension of habeas corpus procedures. Ex parte Milligan (1866) Milligan was an attorney living in Indiana. He was a confederate sympathizer (a Copperhead) and made speeches and organized against the war. He was arrested by the military, found guilty by a military tribunal, and was sentenced to be hanged. He filed a write of habeas corpus in federal court claiming that he should not have been tried by the military and that the President did not have the authority to suspend habeas corpus. The Court said, “It is difficult to see how the safety of the country required martial law in Indiana. If any of her citizens were plotting treason, the power of arrest could secure them, until the government was prepared for their trial, when the courts were open and ready to try them. It was as easy to protect witnesses before a civil as a military tribunal; and as there could be no wish to convict, except on sufficient legal evidence, surely an ordained and established court was better able to judge of this than a military tribunal composed of gentlemen not trained to the profession of the law.” 5 justices said that neither the president nor congress acting separately or together could suspend habeas corpus where civilian courts functioned. 4 justices said that the even though they didn’t use it, Congress has the power to suspend habeas corpus and use military tribunals. Learned Hand Masses v. Patten (1917) – U.S. District Judge Learned Hand ruled that the standard for adjudicating 1st Amendment claims is “incitement to imminent lawless action.” Hand wrote: “To assimilate agitation, legitimate as such, with direct incitement to violent resistance, is to disregard the tolerance of all methods of political agitation which in normal times is a safeguard of free government.” The 1st Amendment protects speech that “stops short of urging upon others that it is their duty or their interest to resist the law,” World War I: Domestic Response Espionage Act of 1917 – Prohibited any attempt to “interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the U.S. . . to cause insubordination . . . in the military or naval forces . . . or willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the U.S.” Sedition Act of 1918 – Prohibited the uttering of, writing, or publishing of anything disloyal to the government, flag, or military forces of the U.S. WWI – Tremendous national fervor and support for the war effort: 4 million Americans in uniform, 1 million sent to fight in Europe, 300,000 killed or seriously wounded. Schenck v. U.S. (1919) A socialist printed 15,000 pamphlets urging resistance to the draft. He sent them through the mail to names of draft-eligible men printed in the newspaper. He was charged with violating the Espionage Act. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. said, "We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing panic." “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Abrams v. United States (1917) Abrams was a Russian immigrant who advocated revolutionary, anarchist, and socialist views. He and his friends published and distributed (by throwing them out of windows of tall buildings) leaflets criticizing President Wilson's decision to send troops to Russia and called for a general strike to protest the policy. The trial court sentenced them for violating the Espionage Act and sentenced them to 15-20 years in prison. The Court upheld the conviction 7-2 and applied the “bad tendency” test: “The language of these circulars was obviously intended to provoke and to encourage resistance to the United States in the war.” In dissent, Holmes said, "Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country. Nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger. . . . The ultimate good is better reached by the free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market." Gitlow v. New York (1925) At issue was a state criminal syndicalism (criminal anarchy) statute, which made it a crime to advocate, teach, aid, or abet in any activity designed to bring about the overthrow of the government by force or violence. The effect of these laws was to outlaw socialist and communist beliefs. Gitlow was a socialist leader in New York who published a pamphlet called "the Left Wing Manifesto" calling for the overthrow of capitalism. The Court held 7-2 that the publication was advocacy and not abstract discussion. It applied the bad tendency test: “A single revolutionary spark may kindle a fire that, smoldering for a time, may burst into a sweeping and destructive conflagration.” Again in dissent, Holmes said, “every idea is an incitement. The only difference between the expression of an opinion and an incitement in the narrower sense is the speaker's enthusiasm for the result. Eloquence may set fire to reason. But whatever may be thought of the redundant discourse before us it had no chance of starting a present conflagration. . . . If in the long run the beliefs expressed in proletarian dictatorship are destined to be accepted by the dominant forces of the community, the only meaning of free speech is that they should be given their chance to have their way.” World War II/Cold War In the 1930 and 40s, the U.S. became self-conscious about its stance on civil liberties in relation to its totalitarian enemies (Russia, Germany, etc.). Also, WWI became more distant and pro civil-libertarian arguments began to win out from time to time. Holmes’ clear and present danger standard re-emerged as good law in Supreme Court opinions. The tide turned however with WWII and the Cold War as anti-communist hysteria began gripping the U.S. The Smith Act (1940) was passed to combat the communist party of America. The Act makes it a crime “to knowingly and willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or by assassination of any officer of such government” or with the intent to cause such overthrow, to publish or display written material advocating the violent overthrow of gvmt.; or to organize or help organize a group to carry out such aims. Dennis v. United States (1951) Dennis was one of 11 leaders of the Communist Party of America convicted for violating the Smith Act. The Court upheld the convictions 6-2. A 4-justice plurality applied a modified clear and present danger test dubbed “grave and probable danger.” “The obvious purpose of the statute is to protect existing government, not from change by peaceable, lawful and constitutional means, but from change by violence, revolution and terrorism.” “Obviously, the [clear and present danger test] cannot mean that before the Government may act, it must wait until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited.” “In each case [courts] must ask whether the gravity of the ‘evil,’ discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.” Dennis v. United States (1951) Justice Hugo Black dissented: “I believe that the ‘clear and present danger’ test does not mark the furthermost constitutional boundaries of protected expression.” “There is hope. . . that in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.” Dennis v. United States (1951) Justice William O. Douglas dissented: “The airing of ideas releases pressures which otherwise might become destructive. When ideas compete in the market for acceptance, full and free discussion exposes the false and they gain few adherents.” “The 1st Amendment provides that ‘Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech.’ The Constitution provides no exception. This does not mean, however, that the Nation need hold its hand until it is in such weakened condition that there is no time to protect itself from incitement to revolution.” “When conditions are so critical that there will be no time to avoid the evil that the speech threatens, it is time to call a halt. . . . On this record no one can say that petitioners and their converts are in such a strategic position as to have even the slightest chance of achieving their aims.” Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) Clarence Brandenburg was convicted for violating an Ohio criminal syndicalism statute which made it a crime to “advocate. . . the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform” or to “voluntarily assemble with any society, group, or assemblage of persons to teach or advocate the doctrines of political syndicalism.” Brandenburg, a leader of the Klan, was convicted for organizing meetings to be televised and broadcast and advocating racial strife during a televised KKK rally. He made such remarks as “Personally, I believe the nigger should be returned to Africa, the Jew to Israel,” and: “We’re not a revengent organization, but if our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengence taken.” Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) In a unanimous opinion, Justice William J. Brennan wrote: “The constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Political Speech Standards Speech Protective<------------------>Speech Restrictive Absolutism Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action [Good Law] Clear & Present Danger Grave & Bad Tendency Probable Danger Black & Douglas in Dennis Brandenburg Holmes in Schenck, Abrams, Gitlow Vinson in Dennis Hand in Masses Majority in Abrams and Gitlow Texas v. Johnson (1989) During the 1984 Republican National Convention re-nominating President Reagan, Johnson burned an American flag in protest. As it was burning, he and his fellow protesters chanted "America, the red, white, and blue, we spit on you." He was charged with violating the Texas flag desecration law, convicted, and sentenced to one year in prison and a $2,000 fine. 47 other states, and the U.S. also had flag-desecration laws. Texas v. Johnson (1989) Justice Brennan delivered the 5-4 majority opinion striking down all flag desecration laws. “Johnson burned an American flag in part of a political demonstration that coincided with the convening of the Republican Party and its renomination of Ronald Reagan for President. . . . Texas claims that its interest in preventing breaches of the peace justifies Johnson’s conviction for flag desecration. However, no disturbance of the peace actually occurred of threatened to occur because of Johnson’s burning of the flag. . . . We do not consecrate the flag by punishing its desecration, for in doing so we dilute the freedom that this cherished emblem represents.”