Error and Uncertainty

advertisement

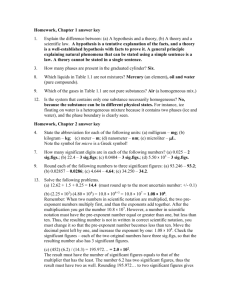

Topic 11: Measurement and Data Processing Honors Chemistry Mrs. Peters Fall 2014 What is Chemistry? Chemistry is the study of the composition of matter and the changes that matter undergoes. • What is matter? – Anything that takes up space and has mass • What is change? – To make into a different form Scientific Process Steps to Scientific Process: 1.Observations: Use your senses to obtain information directly 2.Problem: propose a question based on your observations 3.Hypothesis: Propose an explanation of your problem (If…, then… statement) Scientific Process Steps to Scientific Process: 4. Experiment: Materials list and procedure to test your hypothesis 5. Results: Collection of experiment’s data and analysis of data 6. Conclusion: statements about what your experiment found based on the data collected Measurement in Chemistry • Use the International System of Units (SI) – Aka: the metric system Quantity Unit Symbol Length meter m Volume liter L Mass gram g Temperature Degree Celcius oC Density Grams per cubic cm or grams per milliliter g/cm3 or g/mL Metrics for Honors Chemistry Scientific Units and Devices Device Unit Measurement Balance Gram mass Graduated cylinder Liter volume Meter Stick Meter Length or distance Thermometer Celsius temperature Clock Second Time Measurement in Chemistry Devices to use for taking measurements: – Balance – mass, usually in grams – Ruler – length, usually in cm or mm – Thermometer: temperature, usually in oC – Graduated cylinder: volume, usually in mL 11.1 Uncertainty and errors in measurements EI: All measurement has a limit of precision and accuracy, and this must be taken into account when evaluating experimental results. NOS: Making quantitative measurements with replicated to ensure reliability – precision, accuracy, systematic, and random errors must be interpreted through replication U1 & U2. Types of Data Qualitative Data • Non-numerical data • Usually observations made during an experiment • Use your senses, with exception to taste EX: color, texture, smell, luster, temperature Quantitative Data • Numerical data • Measurements collected during the experiment EX: 5.64 g, 9.25mm A & S 8. Distinguish between precision and accuracy • Precision: how close several experimental measurements of the same quantity are to each other • Accuracy: how close a measured value is to the actual value A & S 8. Precision and Accuracy Low accuracy, low precision Low accuracy, high precision High accuracy, low precision High accuracy, high precision A & S 7. Calculating Error • Error: the difference between the accepted value and the experimental value – Accepted value: the correct value based on reliable resources – Experimental value: value measured in the lab Error = experimental value - accepted value A & S 7. Calculating Percent Error • Percent Error: the relative error, shows the magnitude of the error Percent Error = I error I x 100 accepted value Metrics for Honors Chemistry • • • • • • • • • Metric Prefixes M K H D _ d c m_ _ m Mega (M) 106 Kilo (K) 103 Hecta (H) 102 Deca (D) 101 ORIGIN: meter, liter, gram deci (d) 10-1 centi (c) 10-2 milli (m) 10-3 micro (m) 10-6 U 2. Sig Figs Significant Figures (sig figs): the digits in a measurement up to and including the first uncertain digit • Ex: 62 cm3 = 2 sig figs; 100.00 g = 5 sig figs U 2. Sig Figs Rules for Counting Sig Figs 1. Every nonzero digit represented in a measurement is significant. 24.7 m has 3 sig figs 0.4587 has 4 sig figs 134.798 has ? sig figs 0.6668 has ? sig figs U 2. Sig Figs Rules for Counting Sig Figs 2. Zeros appearing between non zero digits are significant. 70.03 has 4 sig figs 0. 96501 has 5 sig figs 40.30609 has ? sig figs 0.306201 has ? sig figs U 2. Sig Figs Rules for Counting Sig Figs 3. Zeros ending a number to the right of the decimal point are significant 23.80 has 4 sig figs 0.130700 has 6 sig figs 1,006.00 has ? sig figs 0.34090 has ? sig figs U 2. Sig Figs Rules for Counting Sig Figs 4. Zeros starting a number or ending the number to the left of the decimal point are not counted as significant 16000 has 2 sig figs 0.0002709 has 4 sig figs 870,600 has ? sig figs 0.0450 has ? sig figs U 2. Sig Figs General Rule for Counting Sig Figs Start on the left with the first nonzero digit. End with the last nonzero digit OR with the last zero that ends the number to the right of the decimal point U 2. Sig Figs Sig Fig Practice In your notes: copy the problem and write the number of sig figs for each number 1. 34.6 g 2. 56.78 g 3. 4.00670 g 4. 0.000450 g 5. 300.45 g U 2. Sig Figs Sig Fig Calculations 1. Adding/Subtracting: the number of decimal places is important, answer should have same number of decimal places as the smallest number of decimal places 7.10 g + 3.10 g = 10.20 g 22.36 g – 15.16 g = 7.20 g U 2. Sig Figs Sig Fig Calculations 1. Adding/Subtracting: 3.45 g + 3.6 g = 78.645 g – 5.46 g = U 2. Sig Figs Sig Fig Calculations 2. Multiplying/Dividing: the number of sig figs is important, the number with the least number of sig figs determines sig figs in the answer. 0.125kg x 7.2 oC x 4.18kJ kg-1 oC-1= 3.762 kJ round to 3.8 kJ 7.55 m x 0.34 m = U 2. Sig Figs Sig Fig Calculations Practice In your notes: copy the problems and solve. 1. 4.67 g + 3.4 g = 2. 59.74 ml – 45.689 ml = 3. 34.57 g x 23.4 g = 4. 256.8 g / 5.36 g = U 2. Scientific Notation • Scientific Notation is useful for very small and very large numbers. • 0.00000450 is written as 4.50 x 10-6 • 770000000 is written as 7.7 x 108 U 2. Scientific Notation To Convert into Scientific Notation: •move the decimal point so only 1 non-zero digit is to the left of the decimal point. •if you move the decimal point to the left, the power of 10 will be positive (the number is the number of spaces moved) •if you move the decimal point to the right, the power of 10 will be negative. U 2. Scientific Notation Scientific Notation Practice 3,600 = 3.6 x 103 0.000 075 2 = 7.52 x 10-5 5,732,873.912 = ? 0.124 04 = ? U 2. Scientific Notation To Convert out of Scientific Notation: •if the power of 10 is positive move the decimal point to the right the power number of places •if the power of 10 is negative move the decimal point to the left the power number of places. U 2. Scientific Notation Scientific Notation: 8.1 x 10-5 = 0.000081 1.2 x 108 = 120000000 9.342 780 23 x 104 = ? 3.704 x 10-6 = ? U 2. Scientific Notation Scientific Notation Calculations Addition/ Subtraction: exponents must be the same, adjust each number to the same exponent, then add or subtract as usual. U 2. Scientific Notation Scientific Notation Calculations Ex: 5.40 x 103 + 6.0 x 102 = convert 6.0x 102 to 0.60 x 103 5.40x 103 + 0.60x 103 = 6.00x 103 U 2. Scientific Notation Scientific Notation Calculations Multiplication: multiply the coefficients, then add the exponents. (3.0x 104) x (2.0 x 102) = 6.0 x 106 U 2. Scientific Notation Scientific Notation Calculations Division: divide the coefficients, then subtract the exponents. (3.0 x 104) / (2.0 x 102) = 1.5 x 102 U 2. Density Density: The ratio of the mass of an object to its volume Density = Mass Volume units = g/cm3 (solid & liquid) or g/L (gases) U 2. Density Ex: a piece of lead has a volume of 10.0 cm3 and a mass of 114 g, what is it’s density? 114g/ 10.0cm3 = 11.4 g/cm3 11.1 Uncertainty and Error in Measurement • Measurement is important in chemistry. • Many different measurement apparatus are used, some are more appropriate than others. 11.1 Uncertainty and Error in Measurement • Example: You want to measure 25 cm3 (25 ml) of water, what can you use? – Beaker, volumetric flask, graduated cylinder, pipette, buret, or a balance – All of these can be used, but will have different levels of uncertainty. Which will be the best? A & S 1. Systematic Errors • Systematic Error: occur as a result of poor experimental design or procedure. – Cannot be reduced by repeating experiment – Can be reduced by careful experimental design A & S 1. Systematic Errors • Systematic Error Example: measuring the volume of water using the top of the meniscus rather than the bottom • Measurement will be off every time, repeated trials will not change the error A & S 1. Random Error • Random Error: imprecision of measurements, leads to value being above or below the “true” value. • Causes: – – – – Readability of measuring instrument Effects of changes in surroundings (temperature, air currents) Insufficient data Observer misinterpreting the reading • Can be reduced by repeating measurements A & S 1: Random and Systematic Error Systematic and Random Error Example Random: estimating the mass of Magnesium ribbon rather than measuring it several times (then report average and uncertainty) 0.1234 g, 0.1232 g, 0.1235 g, 0.1234 g, 0.1235 g, 0.1236 g Avg Mass= 0.1234 + 0.0002 g A & S 1: Random and Systematic Error Systematic and Random Error Example Systematic: The balance was zeroed incorrectly with each measurement, all previous measurements are off by 0.0002 g 0.1236 g, 0.1234 g, 0.1237 g, 0.1236 g, 0.1237 g, 0.1238g Avg Mass = 0.1236 A & S 8. Distinguish between precision and accuracy in evaluating results Precision: how close several experimental measurements of the same quantity are to each other – how many sig figs are in the measurement. – Smaller random error = greater precision A & S 8. Distinguish between precision and accuracy in evaluating results Accuracy: how close a measured value is to the correct value – Smaller systematic error = greater accuracy • Example: masses of Mg had same precision, 1st set was more accurate. U 5. Reduction of Random Error • Random errors can be reduced by – Use more precise measuring equipment – Repeat trials and measurements (at least 3, usually more) A & S 2. Uncertainty Range (±) • Random uncertainty can be estimated as half of the smallest division on a scale • Always state uncertainty as a ± number A & S 2. Uncertainty Range (±) • Example: – A graduated cylinder has increments of 1 mL – The uncertainty or random error is 1mL / 2 = ± 0.5 mL A & S 2. Uncertainty Range (±) Uncertainty of Electronic Devises On an electronic devices the last digit is rounded up or down by the instrument and will have a random error of ± the last digit. Example: –Our balances measure ± 0.01 g –Digital Thermometers measure ± 0.1 oC State uncertainties as absolute and percentage uncertainties • Absolute uncertainty – The uncertainty of the apparatus – Most instruments will provide the uncertainty – If it is not given, the uncertainty is half of a measurement – Ex: a glass thermometer measures in 1oC increments, uncertainty is ±0.5oC; absolute uncertainty is 0.5oC State uncertainties as absolute and percentage uncertainties • Percentage uncertainty = (absolute uncertainty/measured value) x 100% Determine the uncertainties in results Calculate uncertainty Using a 50cm3 (mL) pipette, measure 25.0cm3. The pipette uncertainty is ± 0.1cm3. What is the absolute uncertainty? 0.1cm3 What is the percent uncertainty? 0.1/25.0 x 100= 0.4% Determine the uncertainties in results Calculate uncertainty Using a 150 mL (cm3) beaker, measure 75.0 ml (cm3). The beaker uncertainty is ± 5 ml (cm3). What is the absolute uncertainty? 5 ml (cm3) What is the percent uncertainty? 5/75.0 x 100= 6.66% 7% Determine the uncertainties in results Percent error = I error l accepted x 100 If percent error is greater than uncertainty, then systematic errors are a problem Random error is estimated by uncertainty, if smaller than percent error, then systematic errors are causing inaccurate data. Determine the uncertainties in results Error Propagation: If the measurement is added or subtracted, then absolute uncertainty in multiple measurements is added together. Determine the uncertainties in results Example: If you are trying to find the temperature of a reaction, find the uncertainty of the initial temperature and the uncertainty of the final temperature and add the absolute uncertainty values together. Determine the uncertainties in results Example: Find the change in temperature Initial Temp: 22.1 ± 0 .1oC Final Temp: 43.0 ± 0.1oC Change in temp: 43.1-22.1 = 20.9 Uncertainty: 0.1 + 0.1 = 0.2 Final Answer: Change in Temp is 20.9 ± 0.2 oC Determine the uncertainties in results Error Propagation: If the measurement requires multiplying or dividing: percent uncertainty in multiple measurements is added together. Determine the uncertainties in results Example: If you are trying to find the density of an object, find the uncertainty of the mass, the uncertainty of the volume, you add the percent uncertainty for each to get the uncertainty of the density. Determine the uncertainties in results Example: Find the Density given: Mass: 25.45 ± 0.01 g and Volume: 10.3 ± 0.05 mL Density: 25.45/10.3 = 2.47 g/mL % uncertainty Mass: (0.01/25.45) x 100 = 0.04% % uncertainty Volume: (0.05/10.3) x 100 = .5% 0.04 + .5 = .54% Final Answer: Density is 2.47 ± .54% Determine the uncertainty in results Uncertainty in Results (Error Propagation) 1. Calculate the uncertainty a. From the smallest division (on a graduated cylinder or glassware) b. From the last significant figure in a measurement (a balance or digital thermometer) c. From data provided by the manufacturer (printed on the apparatus) 2. Calculate the percent error 3. Comment on the error a. Is the uncertainty greater or less than the % error? b. Is the error random or systematic? Explain. 11.2 Graphing EI: Graphs are a visual representation of trends in data. NOS: The idea of correlation – can be tested in experiments whose results can be displayed graphically. U 1. Graphical Techniques Why do are graphs used? • Graphs are an effective means of communicating the effect of the independent variable on a dependent variable, and can lead to determination of physical quantities. U1. Graphical Techniques Example Graph – show the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable Dependent • Graphs are used to present and analyze data. Independent U2. Sketched graphs Example Graph – Have labeled, but unscaled axes – Used to show qualitative trends • Variables that are proportional or inversely proportional Dependent • Sketched graphs: Independent U3. Drawn Graphs Graphs MUST have: • A title • Label axes with quantities and units Mass (g) Candle Mass After Burning Time (min.) U3, A &S 1. Drawn Graphs Graphs MUST have: • Use available space as effectively as possible • Use sensible linear scales- NO uneven jumps • Plot ALL points correctly Mass (g) Candle Mass After Burning Time (min.) A&S 3. Best Fit Lines – drawn smoothly and clearly – Do not have to go through all the points, but do show the overall trend Temperature (oC) Best Fit Lines should be Time (sec) A & S 4 Physical quantities from graphs • Find the gradient (slope) and the intercept • Use y = m x + b for a straight line • • • • y= dependent variable x = independent variable m= the gradient (slope) b = the intercept on the vertical (y) axis A & S 4 Physical quantities from graphs • Ex: to find the slope (m), find 2 data points (2,5) and (4, 10) m= (y2-y1) = (10-5) = 5 = 2.5 (x2-x1) (4-2) 2 A & S 2. Interpretation of Graphs Dependent Variables: Independent- the cause, plotted on the horizontal axis (x-axis) AKA: Manipulated Example Graph Independent A & S 2 Interpretation of Graphs Dependent Variables: Dependent- the effect, plotted on the the vertical axis (y-axis) AKA: Responding Example Graph Independent A & S 2. Interpretation of Graphs Interpolation: determining an unknown value using data points within the values already measured A & S 2. Interpretation of Graphs Extrapolation: when a line has to be extended beyond the range of the measurements of the graph to determine other values – Absolute zero can be found by extrapolating the line to lower temperatures.