Business Plan Information Powerpoint

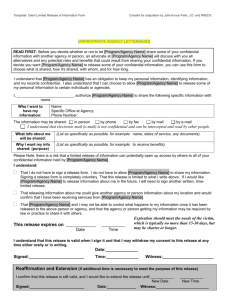

advertisement