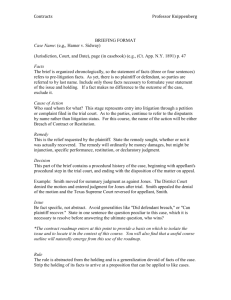

Civ Pro Outline

advertisement