View - American University Washington College of Law

advertisement

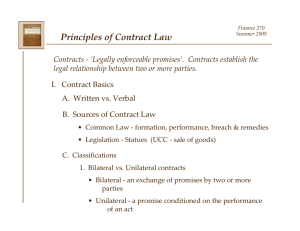

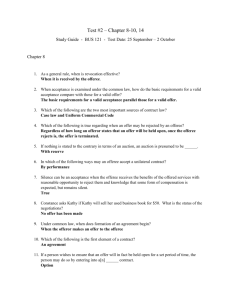

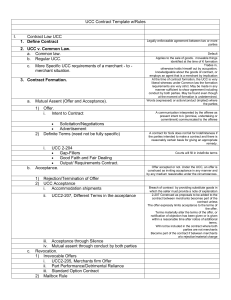

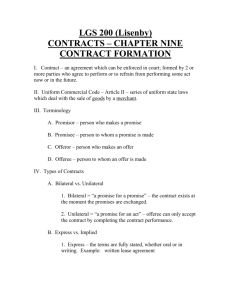

Contracts Outline – Prof. Varona Fall 2009 I. Contract Formation ................................................................................................................. 1 A. Offer ................................................................................................................................. 1 a. Requisite Terms................................................................................................................ 1 b. Termination of offer ..................................................................................................... 2 c. Option contract ................................................................................................................. 2 d. B. Mailbox rule ................................................................................................................. 3 Acceptance ....................................................................................................................... 4 a. Writing (Statute of Frauds) .............................................................................................. 4 b. Assent ........................................................................................................................... 5 c. Methods of Acceptance .................................................................................................... 5 d. C. Mailbox rule ................................................................................................................. 5 Consideration ................................................................................................................... 6 a. Generally – Res. (2d) § 71 .............................................................................................. 6 b. Pre-existing Duty Rule ................................................................................................. 6 c. Effect of no consideration ................................................................................................ 7 d. Unilateral K .................................................................................................................. 7 e. Bilateral K ........................................................................................................................ 7 f. Gratuitous promises.......................................................................................................... 8 iv. II. Implied Contracts ......................................................................................................... 9 Interpretation ........................................................................................................................... 9 A. Differences in contract terms ........................................................................................... 9 a. Mirror Image Rule (CL rule rejected by the UCC) .......................................................... 9 b. Under UCC – Additional terms § 2-207 ..................................................................... 10 iv. Terms known after transaction ................................................................................... 10 B. Parol evidence rule ......................................................................................................... 10 iv. C. Integration of the agreement (R2.s209) ...................................................................... 11 General term interpretation methods .............................................................................. 11 a. Lord Esher’s rules: ......................................................................................................... 11 III. Performance ....................................................................................................................... 12 A. Requirements of performance ........................................................................................ 12 a. Good faith ....................................................................................................................... 12 B. When excused ................................................................................................................ 12 a. Capacity.......................................................................................................................... 12 b. Oppressiveness ........................................................................................................... 13 i c. Behavior ......................................................................................................................... 13 d. Undue Influence – mismatch in bargaining power - Definition. R2.s177 ................. 14 e. Mistake ........................................................................................................................... 15 f. Unconscionabilty............................................................................................................ 16 g. Misrepresentation/Fraud ............................................................................................. 17 h. Commercial Impracticability ...................................................................................... 17 i. Frustration of Purpose .................................................................................................... 18 j. Conditions ...................................................................................................................... 19 k. Efficient breach theory ............................................................................................... 19 IV. Remedies for breach (chosen based on justice and UCC) ................................................. 19 Buyer’s remedies ............................................................................................................... 19 a. i. Expectation ..................................................................................................................... 19 ii. Reliance ...................................................................................................................... 20 iii. Restitution................................................................................................................... 20 iv. Incidental and Consequential Damages ...................................................................... 21 b. Sellers’s remedies .............................................................................................................. 21 i. Expectation ..................................................................................................................... 21 ii. Reliance – same as for buyer ...................................................................................... 22 iii. Restitution................................................................................................................... 22 iv. Incidental damages ..................................................................................................... 22 c. Mitigating Doctrines .......................................................................................................... 22 i. Avoidability.................................................................................................................... 22 ii. Substantial Performance ............................................................................................. 23 d. Liquidated Damages .......................................................................................................... 23 e. Specific performance ......................................................................................................... 23 ii Contracts Outline – Prof. Varona Fall 2009 I. Contract Formation A. Offer a. Requisite Terms i. An offer is “the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain” (R2-s24), which is sufficiently definite and specific about terms, as to “justify another person in understanding that his[her] assent to that bargain is invited” (R2-s24) and bind the parties in K. See Fairmount Glass [offer specified price and quantity and other customary terms could be implied], Harvey v. Facey [expression of lowest reasonable price is not a clear enough offer] ii. An offer must, either explicitly or implicitly: 1. be communicated to the offeree 2. be directed at a particular individual or specified group of persons 3. indicate a desire to enter into a K with the offeree, specifying terms and consideration for the K. a. See Owen v. Tunison (holding that offer specifying that “it would not be possible to accept for less than...” is not definite enough) b. Harvey v. Facey (holding that “lowest price for bumper hall is...” not definite) c. But see Southworth v. Oliver (holding that mailed letter to neighbors specifying the house for sale and price was definite enough) d. Fairmount Glass Works v. Crunden-Martin (quote with specifications in response to particular order request amounted to offer even if industry standard terms are omitted and later added). 4. invite acceptance (specifying, at offeror’s option, mode and time of acceptance) 5. create reasonable understanding that once offer accepted, K final and binding iii. Requirements for promises relied upon for promissory estoppel need not meet all of the above requirements. See promissory estoppel below and Hoffman v. Red Owl Stores iv. Ads are usually not offers, but mere invitations to bargain, except where they contain very definite terms, leaving no room for negotiation, and are clear that offeror intends to be bound. See Lefkowitz v. General MN Surplus (holding that advertisement of specific item for specific price for first person in line is binding and cannot have additional terms later added after acceptance through showing up). v. Offer examined at time of formation for meaning either: 1. Objectively - whether parties appear by their acts, words, and other outward manifestations to agree to be bound (Favored because more reliable results and less likely to impose onto the parties what neither intended). 2. Subjectively - whether parties actually had a meeting of the minds, actually intending to be bound (Disfavored) vi. Where no objective person would believe an offer to be reasonable and where terms are not specific, no enforceable offer exists. See Leonard v. Pepsico (holding that Harrier jet offer could not be believed by a reasonable person and was missing from catalogue). 1 b. Termination of offer i. General rules 1. Under CL, offers are freely revocable until accepted. 2. Offers generally treated as lapsed when: a. Lapse of the offer - reasonable amount of time if not stated 4 An offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated at the time specified in the offer, or, if not time is specified, at the end of a reasonable time. R2.s41 5 What is a reasonable time is a question of fact, depending on all the circumstances existing when the offer and attempted acceptance are made. R2.s41 6 When performance would no longer reasonably serve the purpose of the offer, it is deemed as lapsed. See Loring v. Boston (holding that offer of award for arson during string of the crimes in 1837 no longer valid in 1841). b. Revocation by the offeror (court favors revocation when in doubt) 4 Revocation of offer is effective, and K formation made impossible, when directly or indirectly communicated to offeree. See Dickinson v. Dodds (agreement to hold offer open was unsupported by consideration and Dickinson was notified of sale to other buyer prior to attempted acceptance). 5 An offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated when the offeror takes definite action inconsistent with an intention to enter into the proposed contract and the offeree acquires reliable information to that effect. R2.s43 6 revocation must always originate with the offeror’s actions but may go through a third party in getting to the offeree 7 General offers to the public typically need to be rescinded in the same way that they were promulgated. c. Death or incapacity of offeror or offeree d. Rejection of offer by offeree 3. Cts have treated offers as irrevocable in cases of reasonable and foreseeable reliance (see Substitutes for Consideration –Promissory Estoppel below). Ex: Drennan v. Star Paving (subcontractor not allowed to withdraw bid after general contractor used it because such use was expected and no way to restore status quo by claiming mistake realized after the fact) c. Option contract 1. Under CL, offer irrevocable where there is an option contract, supported separately by consideration. See Dickinson v. Dodds (promise to leave offer open for property was not enforceable because there was no consideration). 2. In goods Ks, UCC 2-205 firm offer provision enables merchant offeror to make irrevocable offer, without consideration, in form of signed writing for a reasonable or specified time (<3months). 2 3. Option contract also created when subcontractor gives bid to general contractor for them to use in submitting an overall bid for the project which they rely upon. See Drannan v. Star Paving Co. (subcontractor not allowed to withdraw bid after general contractor used it because such use was expected and no way to restore status quo by claiming mistake realized after the fact.) 4. The opposite of #4 is not true however because the general contractor suffers detriment when the subcontractor fails to perform but not the other way around. See Holman Erection v. Madsen. 5. Unilateral contracts a. In cases of unilateral contracts (where only performance can constitute acceptance, modern courts recognize an option contract (offer irrevocable) when performance has commenced (R2-s45) b. Performance must be specific to the particular bargained-for project and not general preparation to perform. 4 See White v. Corlies & Tift (carpenter purchased general wood that could be used for any project and therefore performance hadn’t begun); 5 Seeking and obtaining financing in order to be able to agree to purchase does not constitute beginning of performance where not bargained for. See Ragosta v. Wilder 6 But see Ever-Tite Roofing Corp. v. Green (loading of supplies for roofing project and driving to location amounted to beginning performance). c. Performance need not be notified to offeror unless required in offer (Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. (holding that notice was waived by offeror in ad stating that money could be claimed by anyone becoming ill while using product) d. Even if offer specifically states that contract is conditional on acceptance of K and not performance, still will be binding if offeror acquiesces. See Allied Steel and Conveyor v. Ford Motor Co. (holding that provision that offer should be accepted by signing was still binding because performance was allowed at Ford plant). d. Mailbox rule i. Offer’s rejection is effective upon receipt by the offeree. ii. Offeror is the master of acceptance and can dictate what terms apply to the timing of offer and acceptance through the offer. iii. If not specified in offer, risk of acceptance/rejection and revocation passing in the mail falls on offeror. iv. Exceptions – 1. In cases where communications are instantaneous (email, txt messaging) then mailbox rule does not apply and all communications are treated as effective when made 2. Proper dispatch rule then applies meaning relinquishment of control over the item v. See Chart 3 B. Acceptance a. Writing (Statute of Frauds) i. Common law rule requiring written agreements aimed at preventing witnesses and parties from disavowing contracts fraudulently, especially ones difficult to prove orally. ii. Covers 7 major areas (MY LLEGS) (not required in NJ except for land K’s): 1. Promises by an executor to pay debts of the estate out of his/her own assets 2. Contracts to pay debt of another (surety contracts); a. Exceptions novation; See Langman v. Alumni Association of Uni. Of Va. (taking of deed of property donation and its benefits included assumption of mortgage debt through novation). b. Leading object exception when: See Central Ceilings v. National Amusements (owner of building under construction guaranteed payment to subcontractor to complete construction) 4 The surety intends to become liable for the debt in the event of the failure of the primary debtor to perform (i.e., make payment) 5 There was consideration for the promise to guarantee the debt 6 The consideration in exchange for the debt guarantee was primarily for the surety’s benefit. 3. Contracts made in consideration of marriage (typically involving the transfer of property); 4. Contracts for transfer of real estate interest (including sale of land, mortgages, leases, etc.); 5. Contracts not capable (at all) of being performed in full within one year of the date the contract was formed (death may be considered as termination of permanent employment for example but not if there is a clear term of service of greater than one year); 6. Contracts by their terms are not capable of being performed within lifetime of promisor (e.g., promises to bequeath property); 7. UCC Section 2-201(1): Ks for sale of goods where price is = or > $500 (or $5K in some jurisdictions) iii. Promissory estoppel can be used to bar SoF claims. See Monarco v. Lo Greco (child sued for land after it was secretly transferred through will to other child after first child had worked the land for years under promise of eventual ownership). iv. Writing must be signed by the person against whom the agreement is being charged. v. Must contain the essential elements of the agreement that it memorializes. vi. Definition of writing interpreted liberally (includes note, napkin, etc.) 1. Unless additional requirements are prescribed by the particular statute, a contract within the Statute of Frauds is enforceable if it is evidenced by any writing, signed by or on behalf of the party to be charged, which a. reasonably identifies the subject matter of the contract, b. is sufficient to indicate that a contract with respect thereto has been made between the parties or offered by the signer to the other party, and 4 c. states with reasonable certainty the essential terms of the unperformed promises in the contract. R2.s131. vii. Multiple writings allowed to be pieced together in order to constitute an entire agreement – judge determines whether they are connected and normally they need to reference each other. § 132. viii. Signing is any indication intent to be bound by the party and can even include letterhead. (after UETA can be electronic click) 1. The memorandum may consist of several writings if one of the writings is signed and the writings in the circumstances clearly indicate that they relate to the same transaction. R2.s132 b. Assent i. Willingness of parties to be bound by K. Determined either objectively or subjectively like offers at time of formation. ii. Contract assent is examined at the time of its formation favoring the objective approach. See Lucy v. Zehmer (holding that where objective intent appeared to indicate assent, contract was formed). iii. The CL “mirror image” rule requires acceptance to have terms identical to offer; lest it be considered a rejection and counter-offer. Some courts, though, have considered additional terms as precatory or customary. See Fairmount Glass. [standard quality of glass terms not specifically in offer but assumed] iv. In goods Ks, UCC 2-207 dispenses with mirror image rule (see additional terms under interpretation) c. Methods of Acceptance i. Although offer may describe one means of acceptance, and although offeror is “master” of offer and of acceptance req’s, court may still recognize in offer the availability of alternative means of acceptance. See Allied Steel v. Ford (contract only listing one “should” method of acceptance does not preclude other methods especially when performance is allowed anyway). ii. Acceptance of an offer is a manifestation of assent to the terms thereof made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer. R2.s50 iii. Acceptance by performance requires that at least part of what the offer requests be performed or tendered and includes acceptance by a performance which operates as a return promise. R2.s50 iv. Acceptance by a promise requires that the offeree complete every act essential to the making of the promise. R2.s50 v. If no particular method of acceptance is specified by the offeror than any reasonable method is acceptable and K formed upon acceptance per mailbox rule. See International Filter v. Conroe (actual notice of acceptance not needed if offeror does not require it) vi. Silence is generally not permitted as a method of acceptance, except when goods are accepted and retained for an unreasonable period of time/used. See Hobbs v. Massasoit Whip, Co. (whipmaker accepted eel skin from long-term supplier and used it even though no actual order agreement existed) d. Mailbox rule i. The CL Mailbox Rule = unless otherwise specified in offer, acceptance is effective upon proper dispatch 5 ii. Proper dispatch means the relinquishment of control over the item in a way that reasonably anticipates delivery to the other party. iii. If the offer specifies that acceptance must be sent by a particular medium or particular speed, then slow dispatch will not be acceptable. iv. Exceptions 1. If offeree sends rejection or counter- offer and then an acceptance, acceptance effective upon receipt, to protect offeror. (So if offeree first sends rejection, then sends acceptance, K formed if offeror receives acceptance first. If offeror receives rejection first, then acceptance treated as a rejectable counteroffer) 2. If acceptance is part of option contract, then effective upon receipt (not dispatch). 3. In cases where communications are instantaneous (email, txt messaging) then mailbox rule does not apply and all communications are treated as effective when made 4. See Chart C. Consideration a. Generally – Res. (2d) § 71 i. To constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. ii. A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. iii. If the requirement of consideration is met, there is no additional requirement of equivalence in the values exchanged provided that it does not rise to the level of unconscionabilty. R2. S79 (peppercorn standard of old CL since abandoned). iv. The performance may consist of (R2.S75) 1. an act other than a promise, or 2. a forbearance, or a. Forbearance must be made for a reasonable, definable period of time or it will lack the value of consideration (See Strong v. Sheffield (promise to not call debt until he felt like it not consideration because promise was illusory). 3. the creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relation. 4. A return promise. v. The performance or return promise may be given to the promisor or to some other person. It may be given by the promisee or by some other person. R2.S75 b. Pre-existing Duty Rule i. Performance of a legal duty owed to a promisor which is neither doubtful nor the subject of an honest dispute is not consideration. R2.s73 ii. Party already bound to perform an obligation under contract may not coerce the other party into paying a higher consideration for the same performance. See Alaska Packers Association v. Domenico (shipworkers demanded increased wages upon reaching Alaska which was agreed to under coercion and disavowed). iii. Rule not applied where there appears to be no overreaching but a good faith contract, rescission, and new contract. See Watkins and Son v. Craig (digger encountered rock when building basement and negotiated without resistance a higher fee for the rock removal.) 6 iv. If any new duties are created in the new contract then the PED rule can be avoided. c. Effect of no consideration i. Nudum pactum - an agreement not supported by consideration and therefore not enforceable. ii. “Illusory promise” - a promise that does not legally bind promissor to do anything in particular, and therefore cannot constitute consideration. Agreement lacks mutuality. d. Unilateral K i. Definition – exchange of promise in exchange for performance ii. Formed/accepted upon full performance by offeree. iii. Value of the consideration/forbearance can flow back to the promisee in a contract. See Hamer v. Sidway (nephew’s promise to forebear from legal vices in exchange for $5,000 constituted consideration) iv. Past performance cannot be used as consideration for a promise because it was not bargained for before being undertaken. 1. A promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice. Res. § 86 2. A promise is not binding under Subsection (1) a. if the promisee conferred the benefit as a gift or for other reasons the promisor has not been unjustly enriched; or b. to the extent that its value is disproportionate to the benefit. 3. See Feinberg v. Pfeiffer (retirement bonus offered after years of service to employee gratuitous though promissory estoppel might be applicable); 4. See Mills v. Wyman (care for man’s son which led to later promise to compensate by father not enforceable because conscience not replacement for K consideration) 5. But See Webb v. McGowin (promise to pay enforceable for rescuer for saving promisor’s life which also led to injuries to promisee) 6. A satisfaction agreement does not render a contract unenforceable as long as it is performed in good faith. See Mattei v. Hopper (mutuality of contract is not equality; contracts subjecting performance to fancy, taste, or judgment are implied to be upon good faith) e. Bilateral K i. Definition – exchange of promise for another promise 1. Except as stated in §§ 76 and 77 [illusory promises], a promise which is bargained for is consideration if, but only if, the promised performance would be consideration. Res. § 75. ii. Forbearance to assert or the surrender of a claim or defense which proves to be invalid is not consideration unless (Res. § 74) 1. the claim or defense is in fact doubtful because of uncertainty as to the facts or the law, OR 2. the forbearing or surrendering party believes that the claim or defense may be fairly determined to be valid. See See Fiege v. Boehm (allowing for enforcement of K which called for forbearance of a bastardy claim which later was shown to be untrue). 7 iii. Return promise can be implied for consideration purposes where interests of promisor and promisee are linked. See Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon (agreement to find business as licensing agent implied good faith agreement to do a good job when payment was contingent on bringing in business). f. Gratuitous promises i. Nonbinding nature 1. Promises without consideration are generally gratuitous and freely revocable at any time. See Kirksey v. Kirksey (brother-in-law’s promise to widow to offer her a place to live was a gratuitous promise and freely revocable). 2. Exceptions where promissory estoppel exists or in certain cases of pledges, i.e. to charities where general reliance is assumed. ii. Promissory Estoppel 1. A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires. Res. § 90. 2. Promise need not to be so specific as to meet all of the general requirements of a contract offer. See Hoffman v. Red Owl Stores (promise to create a franchise agreement for less than certain amount was enforceable); Cyberchron v. Calldata Systems (promise to come to some agreement while insisting on continued production was a promise that could be reasonably relied upon). 3. May not be found in an implied promise 4. Quitting employment when employable can act as a reasonable reliance when promise is made to pay, especially when promissor intended the reliance. See Ricketts v. Scothorn (promise to pay granddaughter money with interest in order to allow her to stop working.) See also Feinberg v. Pfeiffer Co. (promise to pay retirement bonus/stipend enforceable if worker retired based on it even if no explicit requirement to retire at a particular time). 5. Entitled to use only to prevent injustice not to do justice. See Cohen v. Cowles Media Co.(promissory estoppel claim successful against paper that published name of confidential source despite 1st Amendment concerns). 6. Must find that an actual promise to do something existed before entertaining a promissory estoppel claim. Charter Township of Ypsilanti v. General Motors Corp. (GM’s speech to city council for tax benefit renewal did not constitute definite promise to do anything businesswise) 7. Promise relied upon need not be definite in terms of length of forbearance. See D&G Stout, Inc. v. Bacardi Imports, Inc. (holding that assurances of continued contract support by Bacardi during takeover negotiations was reasonably and foreseeably relied upon preventing immediate revocation of contract). iii. Moral obligation 1. Generally not enforced in contract law because it is amoral. 8 2. Exceptions – a. Promise to pay debt previously discharged in bankruptcy proceedings b. Promise made by a child which is then reaffirmed after adulthood. iv. Implied Contracts 1. Quasi K’s - a restitution remedy where although there is no promise and no true contract, court imposes the legal fiction of one on the parties to avoid unjust enrichment of one of the parties" a. Quantum meruit or quantum valedum – terms used to refer to quasi k’s. See Cotnam v. Wisdom (doctor performed emergency surgery on streetcar victim who eventually died; eligible to collect for services). b. Typically actions of good Samaritans are not compensable unless they are overly burdened in which case a reasonable fee may be charged for services (i.e. doctors). See Cotnam v. Wisdom c. If no legal relationship between these two parties then restitution cannot be sought. See Callano v. Oakwood Park Homes Corp (holding that builder of home not responsible for plant order of home owner who died before finalizing contract and did not notify builder of outstanding debt; cause of action with orderer). d. "to the trier of fact to determine whether or not the defendant has been so unjustly enriched at the detriment of the complainant so as to require him to make compensation therefore." Contractor’s claim (parents required to pay for work requested by their bankrupt daughter which they consented to and which directly benefited them). e. Restitution interest allowed when benefit inured solely to one party at expense of the other by the time of marriage dissolution. See Pyeatte v. Pyeatte (finding that promise of wife to work while husband went to school which was then broken by husband’s divorce was too indefinite to form a K but qualified for restitution) f. In cases of engagement rings, most courts view them as conditional gifts which vest with marriage. 2. "Implied in fact K"- arise where case facts (circumstances, expressions of the parties, etc.)indicate to court that parties intended to make a K but failed to explicitly articulate promises II. Interpretation A. Differences in contract terms a. Mirror Image Rule (CL rule rejected by the UCC) i. Old rule used which found that if offer and acceptance did not match in terms, then the “acceptance” was actually a rejection and counteroffer ii. If acceptance came back with different terms which the offeror performed under, then last shot rule applied which held those terms as binding. iii. Some refinements existed such as: 1. precatory terms – which were suggested terms that did not affect the main contract 2. implied terms – mutual understanding that happened to only be stated in one agreement but was understood in initial offer. 9 b. Under UCC – Additional terms § 2-207 i. Rule 1. A definite and seasonable expression of acceptance or a written confirmation which is sent within a reasonable time operates as an acceptance even though it states terms additional to or different from those offered or agreed upon, unless acceptance is expressly made conditional on assent to the additional or different terms. 2. For contracts with consumers, the additional terms are to be construed as proposals for addition to the contract and not automatically enforceable. 3. Between merchants such terms become part of the contract unless: (a) the offer expressly limits acceptance to the terms of the offer; (b) they materially alter it [the offer]; (c) notification of objection to them has already been given or is given within a reasonable time after notice of them is received. 4. Conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of a contract is sufficient to establish a contract for sale although the writings of the parties do not otherwise establish a contract. In such case the terms of the particular contract consist of those terms on which the writings of the parties agree, together with any supplementary terms incorporated under any other provisions of this Act. ii. Application – 1. Silence cannot act as an acceptance of additional terms that substantially alter the agreement, including arbitration clause. See Dorton v. Collins & Aikman (arbitration clause on back of acknowledgement form which had been used over time). UCC § 2-207(1). 2. If seller ships despite buyer’s lack of acceptance of a “conditional” term then conditionality not applicable. 2-207(3) only enforces agreed upon provisions and gap fillers (good faith, reasonable delivery, warranties, etc) a. Used only when conduct suggests a contract though one doesn’t exist under 207(1) or 207(2). iii. See chart for Analysis iv. Terms known after transaction 1. If product is purchased without any mention to limited warranty or license, later provisions may not be added under § 2-207(2). See Step Saver v. Wyse Technology (software sold without mention of limitations of use which were only later put on the box-tops that were shipped). 2. If there is mention of the licenses apparent at time of purchase, all terms do not need to be displayed up front as long as provision for return of the product is made if the additional terms are rejected. See ProCD v. Zeinberg (CD purchased had sticker on packaging which also had popup read-me’s/license agreements each time it was run). B. Parol evidence rule a. Definition – 10 i. When written contract is final and complete expression of their agreement (i.e., a complete integration)- neither party may later raise pre-writing parol evidence (oral or written) to supplement (add to), clarify/explain or contradict the writing. ii. When the written contract is not a complete and final expression of the parties’ agreement, a party may raise consistent (and not contradictory) parol evidence to supplement or explain terms in the writing not completely and finally expressed iii. A binding, partially integrated written agreement discharges prior inconsistent agreements but allows the addition of consistent terms. R2.s213, 215, 216 iv. Integration of the agreement (R2.s209) 1. An integrated agreement is a writing or writings constituting a final expression of one or more terms of an agreement (Ct uses 4 corners test in analyzing completeness including requisite terms) 2. Whether there is an integrated agreement is to be determined by the court as a question preliminary to determination of a question of interpretation or to application of the parol evidence rule. 3. Where the parties reduce an agreement to a writing which in view of its completeness and specificity reasonably appears to be a complete agreement, it is taken to be an integrated agreement unless it is established by other evidence that the writing did not constitute a final expression. 4. Integration is determined as a preliminary judgment prior to the analysis of the parol evidence. v. Where a reasonable person would anticipate a term being included in a contract, especially when the consideration for the promise is included, the court will likely not admit parol evidence. See Gianni v. Russel (exclusive drink sale right not included despite addition of prohibition on tobacco sales). vi. Collateral agreements allowed if it could naturally have been separate and the main contract is not entirely integrated. See Masterson v. Sine (collateral agreement that option on land was not assignable to non-family members allowed). vii. Parol evidence rule does not block the introduction of evidence to prove mistake or fraud despite complete integration especially when performance indicates mistake. See Bollinger v. Central Penn Stripping (term was dropped from contract requiring sandwiching of waste between soil though performance had followed provision for months prior). viii. Merger clause may be used in the contract to completely prevent the admission of parol evidence. C. General term interpretation methods a. Lord Esher’s rules: i. Ejusdem generis – of the same kind ii. Expressio unius est exclusio alterius – the expression of one thing is the exclusion of another iii. Noscitur a sociis – it is known from its associates iv. Contra proferentem – against the proferror/author b. Contract terms are interpreted objectively not subjectively, by reference to the contract’s plain language and context, the parties’ conduct, trade usage, and customary meaning. See Frigaliment Importing Co. v. BNS Int’l Sales (court defined chicken as any size/age bird using industry standards). 11 III. Performance A. Requirements of performance a. Good faith i. Every contract imposes upon each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance and in its enforcement. R2.s205 ii. “Good faith” means honesty in fact in the conduct of the transaction concerned. UCC 1-201(19) (industry specific). iii. A satisfaction agreement does not render a contract unenforceable as long as it is performed in good faith. See Mattei v. Hopper (mutuality of contract is not equality; contracts subjecting performance to fancy, taste, or judgment are implied to be upon good faith; contract was for purchase of strip mall with leased spots) iv. “A term which measures the quantity by the output of the seller or the requirements of the buyer means such actual output or requirements as may occur in good faith, except that no quantity unreasonably disproportionate to any stated estimate or in the absence of a stated estimate to any normal or otherwise comparable prior output or requirements may be tendered or demanded.” – UCC § 2-306(1); See Eastern Airlines v. Gulf Oil (agreement to provide airline’s fuel needs was enforceable as long as there was not extreme deviation from expectations, i.e. good faith). v. Party must agree to correctly follow in good faith its own policies and procedures under the contract in order to avoid breach. See Dalton v ETS (College Board refused to appropriately consider evidence submitted by Dalton to contest cheating). B. When excused a. Capacity i. Certain groups presumptively unable to enter into contracts (at least historically): 1. Age a. Historically 21 in many jurisdictions but now mostly 18 (even for emancipated minors) b. Vendors run risk of minor disaffirming contract if they choose to sell to those who could be a minor c. Minor must disaffirm before maturity or soon after reaching the age of majority. d. After rescission of contract, must return property to seller in whatever condition it is in. e. Exceptions – necessities-based contracts unable to be disaffirmed, and a reaffirmation of a contract after reaching maturity prevents later disaffirming. See Keifer v. Fred Howe Motors (emancipated minor rescinded purchase contract for car after reaching age of majority) 2. Mental illness a. A person incurs only voidable contractual duties by entering into a transaction if by reason of mental illness or defect i. he is unable to understand in a reasonable manner the nature and consequences of the transaction, OR ii. he is unable to act in a reasonable manner in relation to the transaction and the other party has reason to know of his condition. 12 b. Where the contract is made on fair terms and the other party is without knowledge of the mental illness or defect, the power of avoidance under Subsection (1) terminates to the extent that the contract has been so performed in whole or in part or the circumstances has so changed that avoidance would be unjust. In such a case a court may grant relief on such equitable terms as justice requires. R2.s15 c. See Ortelere v. Teachers Retirement Board (mentally ill woman changed her annuity payments and then died forfeiting large sum. Husband not informed of the change and the school board knew of her condition). d. See also Cundick v. Broadbent (“mental capacity to contract depends upon whether the allegedly disabled person possessed sufficient reason to enable him to understand the nature and effect of the act in issue” where contracting involved great deliberation and no one, including family acting as “guardian” in contract, was aware of mental condition.) 3. Intoxication – contracting individual must be able to comprehend the nature and consequences of the instrument executed. See Lucy v. Zehmer (contracting for sale of land at bar but corrected grammar and put in title term). 4. Married women 5. Sailors b. Oppressiveness i. Specific enforcement of a contract may be refused if 1. The consideration for it is grossly inadequate or its terms are otherwise unfair, or 2. Its enforcement will cause unreasonable or disproportionate hardship or loss to the defendant or to third persons, or 3. It was induced by some sharp practice, misrepresentation, or mistake. R2.s367 ii. Court always retains discretion in enforcement of equitable remedies (ie. Specific performance). See McKinnon v. Benedict (small loan for land development led to long-term strict restrictions on land use and therefore specific performance denied). iii. Measured at time of agreement based on expected burdens of each party rather than actual. See Tuckwiller v Tuckwiller (woman agreed to carry for aunt for the rest of her life in exchange for being willed farm. Woman died shortly thereafter but K still enforceable). c. Behavior i. Duress 1. Undue pressure or threats of bodily injury, harm, imprisonment, or economic harm, or other means of coercion that induce another party to undertake an act (e.g., enter a contract) contrary to his or her free will. 2. If a party’s manifestation of assent is induced by an improper threat by the other party that leaves the victim no reasonable alternative, the contract is voidable by the victim. R2.s175 See 3. A threat is improper if (R2.s176) 13 a. what is threatened is a crime or a tort, or the threat itself would be a crime or a tort if it resulted in obtaining property, b. what is threatened is a criminal prosecution, c. what is threatened is the use of civil process and the threat is made in bad faith, d. the threat is a breach of the duty of good faith and fair dealing under a contract with the recipient. 4. A threat is improper if the resulting exchange is not on fair terms, and (R2.s176) a. the threatened act would harm the recipient and would not significantly benefit the party making the threat, b. the effectiveness of the threat in inducing the manifestation of assent is significantly increased by prior unfair dealing by the party making the threat, or c. what is threatened is otherwise a use of power for illegitimate ends. 5. Exceptions a. Party cannot give in too easily b. Threat to bring legal action does not generally rise to the level of coercion (regularly broken) c. Threat to do something legal typically not coercive i. Exceptions 1. threat to terminate employee without non-compete agreement signed 2. Threat of divorce without signing mid-marriage property agreement not allowed through surprise on day of wedding or soon thereafter (note 2, p. 326) 6. Economic Duress - See Austin Instruments v. Loral Corp. (economic duress or business compulsion is demonstrated by proof that ‘immediate possession of needful goods is threatened’. . . .or more particularly, in cases such as the one before us, by proof that one party to a contract has threatened to breach the agreement by withholding goods unless the other party agrees to some further demand. . . . It must also appear that the threatened party could not obtain the goods from another source. . .and that the ordinary remedy of an action for breach of contract would not be adequate.) d. Undue Influence – mismatch in bargaining power - Definition. R2.s177 a. Undue influence is unfair persuasion of a party who is under the domination of the person exercising the persuasion or who by virtue of the relation between them is justified in assuming that the person will not act in a manner inconsistent with his welfare. b. If a party’s manifestation of assent is induced by undue influence by the other party, the contract is voidable by the victim. 2. Indicators of Undue influence – a. discussion of the transaction at unusual or inappropriate times, b. consummation of the transaction in an unusual place c. insistent demand that the business be finished at once d. extreme emphasis on untoward consequences of delay e. use of multiple persuaders by the dominant side against a single servient party 14 f. absence of third party advisers g. statements that there is no time to consult financial advisers or attorneys. h. See Odorizzi v. Bloomfield School District (gay teacher threatened with firing and criminal prosecution if he did not resign immediately during meeting at his home with superintendent). e. Mistake i. Definition – a belief that is not in accord with the facts. R2.s151 ii. Unilateral 1. Where a mistake of one party at the time a contract was made as to a basic assumption on which he made the contract has a material effect on the agreed exchange of performances that is adverse to him, the contract is voidable by him if he does not bear the risk of the mistake under the rule stated in § 154, and (a) the effect of the mistake is such that enforcement of the contract would be unconscionable, or (b) the other party had reason to know of the mistake or his fault caused the mistake. R2.s153 2. In addition, the party seeking relief must give prompt notice of his election to rescind and must restore or offer to restore to the other party everything of value which he has received under the contract. Both from Elsinore v. Kastorff (allowing rescission where general contractor messed up calculation resulting in substantially lower bid than intended) iii. Mutual 1. Where a mistake of both parties at the time a contract was made as to a basic assumption on which the contract was made has a material effect on the agreed exchange of performances, the contract is voidable by the adversely affected party unless he bears the risk of the mistake under the rule stated in § 154. R2.s151(1) 2. Subjective evidence may be used in order to prove that a meeting of the minds did not occur and that the parties did not actually agree to the same material terms and therefore no mutual assent/contract exists. See Raffles v. Wichelhaus (2 ships Peerless) 3. When any one of the terms used to express an agreement is ambivalent, and the parties understand it in different ways, there cannot be a contract unless one of them should have been aware of the other’s understanding. See Oswald v. Allen (buyer and seller believed that they were talking about different coin collections during the sales process and therefore no contract). 4. No mutual mistake exists when there is no mistake as to identity of the subject matter of the agreement but only to its value. See Wood v. Boynton (diamond in the rough case) 5. Mutual mistake does exist when the thing contracted for in fact is fundamentally different from that which was understood. See Sherwood v. Walker (pregnant cow case) 6. Land sold in order to grow a particular crop on it with a common assumption of available water may be returned if not commercially farmable but same is not true for undiscovered minerals. See Renner v. Kehl (bought land to grow jojoba but no water present. Only entitled to recover purchase payments but still had to pay reasonable rent). 15 iv. Remedy 1. Typically the contract is voided and each side bears its own damages as a result. f. Unconscionabilty i. Adhesion contracts 1. Take-it-or-leave-it bargaining based on fixed terms that are often common throughout an industry 2. Generally enforceable unless terms are surprising or unconscionable. a. Surprising i. Where contracts written so as to confuse the weaker party ii. Language does not reflect what was reasonably expected of the agreement. See Klar v. H & M Parcel Room (court refused to enforce $25 liability limit on stored packages when contained in fine print on the claim slip). b. Unconscionable i. “such a contract or provision which does not fall within the reasonable expectations of the weaker or ‘adhering’ party will not be enforced against him [or her].” ii. “a contract or provision, even if consistent with the reasonable expectations of the parties, will be denied enforcement if, considered in its context, it is unduly oppressive or ‘unconscionable’”. iii. See Graham v. Scissor-Tail Inc. (refusing to enforce arbitration clause that involved a heavily biased arbitrator, other party’s union). ii. General 1. Cannot use excuse of failure to read as a defense to contract enforcement. See Simeone v. Simeone (wife tried to disavow a pre-nuptial agreement by saying she was under undue influence and hadn’t read it despite negotiation). 2. See Carnival Cruise Lines v. Shute (court enforced choice of forum clause that was on ticket because ticket “could” have been returned and domestic forum in Florida not unreasonable given international travel of ships). 3. Exculpatory clauses found as valid in adhesion contract when no objection was raised and there were multiple sellers despite tight market. See O’Callaghan v. Waller & Beckwith Realty (allowing release of liability clause in lease) (many legislatures have refused to recognize these provisions). 4. Dragnet clause is typically held as unconscionable because represents great disparity of bargaining power. See Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. (installment contract which allowed seizure of all past purchases not enforceable). 5. Price alone can at times make a contract unconscionable. See Jones v. Star Credit Corp. (predatory sale/financing scheme of refrigerator was not enforceable and only allowed for payment equal to fair value of fridge). 6. Courts should not enforce contracts which encourage criminal actions/entities. See XLO Concrete v. Rivergate Corp. (mafia involved in 16 kickbacks on concrete contracts in part through force; still must prove that price paid was higher than would be expected without mafia). 7. Contract may be deemed unconscionable as a matter of public policy, such as surrogacy contract. In the Matter of Baby M. (expenses of birth may be reimbursed but not for actually carrying/handing over the baby). 8. Remedy – UCC 2-302 (a mirrored in restatement) a. If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to avoid any unconscionable result. b. When it is claimed or appears to the court that the contract or any clause thereof may be unconscionable the parties shall be afforded a reasonable opportunity to present evidence as to its commercial setting, purpose and effect to aid the court in making the determination. g. Misrepresentation/Fraud i. No liability in contract law for bare non-disclosure (though some state’s have laws). See Swinton v. Whitinsville Sav. Bank (sale of home without disclosure of termite infection did not allow for voiding of K. ii. Elements 1. Can be found even where the party committing it had no knowledge of their statement's falsehood 2. Misrepresentation that had little effect on the contract itself will not justify rescission 3. Reliance on misrepresentation must be reasonable iii. Where a representation of some aspect of the purpose is given, the entire truth must be disclosed or rescission is allowed. See Kannavos v. Annino (buyer relied on house advertisement that clearly indicated it was for multi-family rental when owners knew that it was in violation of municipal codes, rescission allowed even without additional investigation by the buyer). iv. If a party to the contract does choose to speak, even if not required, he is required to speak honestly and divulge all of the facts within his knowledge v. In capacity of teacher/dance expert, burden of telling the whole truth is higher when the buyer relies on their advice as fact. See Vokes v. Arthur Murray (old woman relied on inaccurate “evaluations” indicating substantial improvement and need for additional lessons in purchasing). vi. Fraud in underlying contract can open the door to a quantum meruit claim. See Jesse Ventura v. Titan Sports, Inc. (court found that misrepresentation about other wrestler’s contract privileges allowed Ventura to recover for amount of others’ K benefits). h. Commercial Impracticability i. Old rule – Performer was required to do all things under heaven and earth to meet his obligation under contract. See Stees v. Leonard (building fell down twice during construction because of poor land). ii. Current Rule - Where after a contract is made, a party’s performance is made impracticable without his fault by the occurrence of an event the non-occurrence 17 iii. iv. v. vi. vii. viii. ix. x. xi. of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made, his duty to render that performance is discharged, unless the language or the circumstances indicate the contrary. R2.s261. similar under R2.s615 where seller unable to perform. Test: 1. Contingency, something unexpected, must have occurred 2. The risk of the non-occurrence was not allocated by the agreement or custom 3. Occurrence of the contingency rendered performance impracticable (performance can only be done at an excessive and unreasonable cost. See Transatlantic Financing Corp v. US (ship forced to take long route because of closing of the Suez Canal). "personal" service contracts are excused with death of promisor - ie. Artist commissioned to paint something dies half way through (any unearned commissions returned) Supervening illegality - legislature steps in to prevent performance under the contract Party not excused from performance if they cause or assume the risk of the supervening circumstance. See Taylor v. Caldwell (performance hall excused from lease when hall burnt down without any fault). Seller excused if understood supplier, cited in the contract, goes out of business and therefore can no longer provide needed item. See Selland Pontiac-GMC v. King (chasis manufacture for school bus went out of business). But seller not excused if they took no steps to ensure that their supply would be available to perform contract. See Canadian Industrial Alochol v. Dumbar Molasses (supplier not excused by lower than normal production by supplier when no steps were taken to contract for supply ahead of time). Where a contract specifically chooses an indicator to account for market changes, it will be enforced so long as it exists. See Eastern Airlines v. Gulf Oil (indicator of crude oil no longer reflective of actual market prices after government imposed two-tier pricing system). Increase in costs would have to be unconscionable (bankruptcy-level) to excuse performance and burden is on breacher to prove. See Eastern Airlines v. Gulf Oil. Force Majeure – liquidated impracticability clause 1. Lists what would be considered an occurrence to render performance impracticable 2. If too general K lacks mutuality but if too specific not useful i. Frustration of Purpose i. In order for a contract to be avoidable for frustrated purpose: 1. A party's principal purpose is substantially frustrated 2. Without his/her fault 3. By the occurrence or non-occurrence of an event that was a 4. Mutual assumption as purpose of contract. R2. S265 ii. Day-time lease of a property which is advertised for a purpose and rented for the same purpose, even if unstated, will be avoidable if the purpose does not occur. See Krell v. Henry (property leased on coronation route became worthless during the daytime when event postponed). 18 iii. Transportation provided by common carrier not typically affected by cancellation of ultimate event because pricing and service only indirectly affected by event. See Krell v. Henry (Derby Day taxi). j. Conditions i. A condition is an event, not certain to occur, which must occur, unless its nonoccurrence is excused, before performance under a contract becomes due. R2.s224 1. Express - in contract or clearly understood as requirement through language or behavior of the parties (includes implied-in-fact conditions) 2. Constructive (implied-in-law) condition - not agreed to implicitly but imposed upon the contract as a matter of law to avoid injustice; if contract above is silent on when payment is due, then court will impose the delivery as a condition of payment a. Condition precedent -condition that must occur before performance is due (ie delivery before payment) b. Condition subsequent -used to discharge a duty after a particular condition is met; failure to file claim after deadline following accident k. Efficient breach theory i. Law should not discourage breach when the loss to the breaching party if contract honored would exceed damages to victim of breach. Pareto-improving situation ii. Contract law not intended to punish breaching party beyond the damages of the party who did not breach. US Naval Institute v. Charter Communications, Inc. (not allowing for award of profits of breaching party for early paperback release beyond the lost income from hardcover sales) IV. Remedies for breach (chosen based on justice and UCC) a. Buyer’s remedies i. Expectation 1. Definition – attempts to put the non-breaching party into the same position they would be in if the contract had been performed. 2. Measured as the difference between the value of what is expected and what is actually received from performance including any incidental consequences fairly within the contemplation of the parties when they made their contract but excluding any burden that would have been inflicted with normal performance. Hawkins v. McGee (hairy hand case) 3. “Cover”; Buyer’s Procurement of Substitute Goods UCC 2-712(1) a. buyer may “cover” the seller’s failure to deliver or the buyer’s good faith rejection of goods by “making in good faith and without unreasonable delay any reasonable purchase of or contract to purchase goods in substitution for those due from the seller.” b. The buyer may recover from the seller as damages the difference between the cost of cover and the contract price together with any incidental or consequential damages as hereinafter defined, but less expenses saved in consequence of the seller’s breach. c. Failure of the buyer to effect cover within this section does not bar him from any other remedy. 19 d. Covering precludes the buyer from seeking to recover based on market price if he finds a better deal. 4. Calculation = (loss in value + other loss) - (costs avoided + loss avoided) a. “loss in value” = the difference to injured party between the contracted performance and what was actually received (e.g., K price - price actually received) b. “other loss” = additional expenses resulting from breach, including property and physical harm, substitution or replacement costs, etc. c. “costs avoided” = the injured party’s costs savings from not having to perform full K (e.g., labor costs) d. “loss avoided” = the injured party’s prevention of loss in resources from not having to perform full K (e.g. wear and tear, etc.) e. Non Cover - Buyer who elects not to or cannot “cover” following breach may recover damages equal to the difference between contract price and market price for hypothetical sale at the time buyer learned of breach and not based on actual damages even if windfall is realized. UCC 2-713. See Tongish v. Thomas (middleman had his contract rescinded by end-buyer and therefore recovered more than actual damages from initial breaching supplier). ii. Reliance 1. Definition – attempts to restore non-breaching party to the position it was in before the contract was entered into. 2. Used in some medical situations in because of difficulty in quantifying the outcome of a surgery that was unsuccessful. See Sullivan v. O’Connor (applying reliance to award difference between original nose and post-surgery non-Heidi Lamar nose) 3. Appropriate in cases of promissory estoppel rather than expectation damages. See Eby v. York-Division (even if employment is at-will, unfulfilled employment promise which foreseeably induces moving expenses, time-off from work to prepare can be recovered under reliance). iii. Restitution 1. Definition – attempts to return anything of value given to breacher in order to avoid unjust enrichment. Quantum meruit 2. Restitution damages appropriate where the breachee does not want/need the contract to be fulfilled. 3. Restitution damages are not reduced by the amount of avoided costs. See United States v. Algernon Blair, Inc. (city cancelled contract to build bridge when road cancelled) 4. Contract can be a good indicator of the reasonable value of the services for remedies purpose 5. Buyer may recover any payments or deposits made to seller, before seller withheld delivery or stops performance because of the buyer’s breach or insolvency. UCC allows buyer to recover payments above and beyond any reasonable liquidated damages provided for by contract (or if no liquidated damages expressly provided for in K, then the lesser of 20% of total value of buyer’s performance under K or $500). UCC 2-718(2) 20 6. Limits the buyer’s right to restitution of any payments allowed by 2-718(2) by means of an offset, which includes (in 2-718(3)(a)) any damages due to the seller under Article 2 of the UCC. UCC 2-718(3). iv. Incidental and Consequential Damages 1. Incidental damages - expenses reasonably incurred in inspection, receipt, transportation and care and custody of goods rightfully rejected, any commercially reasonable charges, expenses or commissions in connection with effecting cover and any other reasonable expense incident to the delay or other breach. 2. Consequential damages - resulting from the seller’s breach include a. any loss resulting from general or particular requirements and needs of which the seller at the time of contracting had reason to know and which could not reasonably be prevented by cover or otherwise; and b. injury to person or property proximately resulting from any breach of warranty. UCC 2-715. 3. Unforeseeability and Related Limitations on Damages R2.s351 a. Damages are not recoverable for loss that the party in breach did not have reason to foresee as a probable result of the breach when the contract was made. b. Loss may be foreseeable as a probable result of a breach because it follows from the breach i. in the ordinary course of events, or ii. as a result of special circumstances beyond the ordinary course of events, that the party in breach had reason to know. c. Typically must be made explicitly clear to the other party. See Hadley v. Baxendale (shipper’s slowness in delivery did not result in liability for mill shutdown because shipper not aware of implications of delay). d. Loss in expected jump in property values was not a reasonable and foreseeable risk of construction project breach. See Kenford Co. v. County of Erie (county cancelled construction of football stadium which plaintiff had bought the land surrounding) e. Damages to impact on career, however, are awardable if it is reasonable to foresee harm. See Redgrave v. Boston Symphony Orchestra (concert cancelled after political remarks) f. Foreseeability can be implied based on industry standards or experience. See Torrington v. Fort Pitt (supplier delayed in delivering structural steel for project which required additional expense to install before freeze). b. Sellers’s remedies i. Expectation 1. Resale - where the buyer breaches, seller can resell the goods at issue and, if done in good faith and a “commercially reasonable” way, seller can recover “difference between the contract price and the resale price.” UCC 2-706 2. No Resale - where a buyer breaches, seller can opt not to resell the goods at issue, and instead recover “difference between the market price at the time and place for tender and the unpaid contract price….” UCC 2-708(1) 3. Market Price Inadequate - if the calculation in 2.708(1) “is inadequate to put the seller in as good a position as performance would have done” then “the measure 21 of damages is the profit (including reasonable overhead) which the seller would have made from full performance by the buyer…..” UCC 2-708(2) 4. Lost volume seller rule a. Seller must have a continuous, inexhaustible supply of its products, finite number of customers, and can meet and realize profits from all new orders. b. Claimant bears the burden of showing that it is a lost-volume seller. See R.E. Davis Chemical Corp. v. Diasonics (medical device sale breached by buyer who had limited customers). ii. Reliance – same as for buyer iii. Restitution 1. Available to the seller when, inter alia, the buyer has accepted the goods and not paid for them. In such a case, seller can recover contract price of goods. UCC 2709 iv. Incidental damages 1. Include any commercially reasonable charges, expenses or commissions incurred in stopping delivery, in the transportation, care and custody of goods after the buyer’s breach, in connection with return or resale of the goods or otherwise resulting from the breach. UCC 2-710 c. Mitigating Doctrines i. Avoidability 1. Breachee typically has a duty to mitigate damages after being informed of the breach: R2.s350 a. Except as stated in Subsection (2), damages are not recoverable for loss that the injured party could have avoided without undue risk, burden or humiliation b. The injured party is not precluded from recovery by the rule stated in Subsection (1) to the extent that he has made reasonable but unsuccessful efforts to avoid loss. 2. Exception to halting work - Where the goods are unfinished an aggrieved seller may in the exercise of reasonable commercial judgment for the purposes of avoiding loss and of effective realization either complete the manufacture and wholly identify the goods to the contract or cease manufacture and resell for scrap or salvage value or proceed in any other reasonable manner. UCC 2-704(2). 3. After notice, construction company cannot continue to build something that is not desired/useful to the breacher. See Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge Co. (bridge to nowhere was completed after city ordered contract rescinded and decided not to build the road leading to it). 4. Mitigation by a wrongfully discharged employee – remedy is the amount of salary agreed upon for the period of service, less the amount which the employer affirmatively proves the employee has earned or with reasonable effort might have earned from the other employment. [BUT…] The employer must show that the other employment was comparable, or substantially similar, to that of which the employee has been deprived. See Parker v. Twentieth-Century Fox (offer of a western movie in place of cancelled dance movie not viewed as a reasonable substitute). 22 ii. Substantial Performance 1. When performance is incomplete but meets the essential purpose of the contract and done in good faith then only damages should be awarded. 2. Doctrine not applicable when conditions are expressly stated in contract. 3. When the cost of fixing the defect through replacement is grossly and unfairly out of proportion to the difference in value or wasteful, the court may award only the diminution in the value between the defective and expected performance, especially when substitution/defect was not willful. See Jacob & Youngs v. Kent (pipe that was not made in Reading according to the pipe was accidentally used but of same quality). See also Plante v. Jacobs (some minor aesthetic issues needed to be fixed and all placed in wrong place but with little effect on actual value). d. Liquidated Damages i. Definition - attempt to reasonably estimate actual damages of breach ahead of time through contract ii. Damages for breach by either party may be liquidated in the agreement but only at an amount which is reasonable in the light of the anticipated or actual harm caused by the breach and, in a consumer contract, the difficulties of proof of loss, and the inconvenience or nonfeasibility of otherwise obtaining an adequate remedy. UCC 2-718 and effectively R2.s356(1) iii. Enforceability – Enforceable so long as they are reasonable estimates at time of contract or at breach of actual damage and not designed to punish breach (no penalty clauses). See Wasserman’s Inc. v. Township of Middletown (property lease included provision for payment of percentage of gross profits which appears on its face to be a penalty). iv. Effect of penalty clauses allowed if flipped into incentives based on delivery date. v. Clauses especially applicable when: 1. Damages are typically difficult to measure, and 2. Fair estimate of actual losses and incidental costs e. Specific performance i. Used as an equitable remedy when justice requires. ii. Specific performance may be decreed where the goods are unique or in other proper circumstances. In a contract other than a consumer contract, specific performance may be decreed if the parties have agreed to that remedy. However, even if the parties agree to specific performance, specific performance may not be decreed if the breaching party’s sole remaining contractual obligation is the payment of money (would prevent efficient breaches). UCC 2-716. iii. Court allows specific performance when goods unique and virtually impossible to obtain on the open market and the goods were particularly important to the company's products. See Campbell Soup v. Wentz (contracted for carrots were sold to another vendor because of price increase during extreme shortage) iv. Difficult to quantify the damages that would be received by using other similar products also encourages this remedy. See Campbell Soup v. Wentz v. Not appropriate where a comparable product is available on the market as a cover even if the price is higher (monetary damages more appropriate). See Klein v. PepsiCo (purchase of jet fell through at the last minute but comparable aircraft were available on the market at time of breach). 23 Attachments Additional terms chart Mailbox Rule Sanity Chart Parol Evidence chart 24