Chapter 23 Summary - Biloxi Public Schools

advertisement

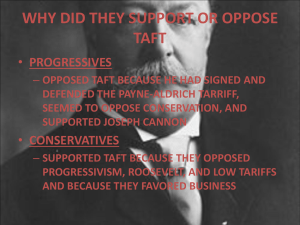

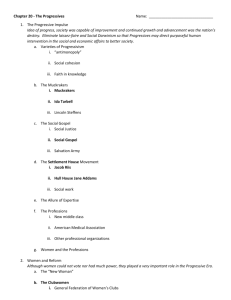

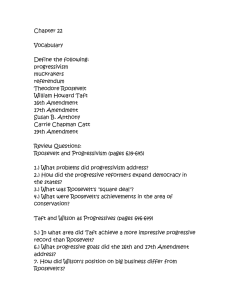

CHAPTER 23 FROM ROOSEVELT TO WILSON IN THE AGE OF PROGRESSIVISM THE REPUBLICAN SPLIT The author begins with the growing personal split between Teddy Roosevelt and his hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft. The split allowed the Progressive wing of the Democratic party to win the White House. THE SPIRIT OF PROGRESSIVISM Progressives never organized into a coherent movement, but shared a general set of values. They tended to combine a sense of evangelical Protestant duty with faith in the benefits of science. The result was a tremendous confidence in their ability to improve every aspect of American life, by law if necessary. A. The Rise of the Professions Progressive attitudes were especially strong among the young men and women who entered law, medicine, business, education, and social work. Proud of their skills, they made these occupations into professions by requiring tough entrance requirements and by forming national associations. B. The Social-Justice Movement Reformers realized that helping individuals here and there was not enough and turned their attention to larger social problems, such as poverty, bad housing and low wages, which they attacked with scientific precision. C. The Purity Crusade Progressives fought successfully against such vices as prostitution and alcohol. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union pressured nineteen states to adopt prohibition laws and played a pivotal role in pushing through the Eighteenth Amendment. D. Woman Suffrage, Woman’s Rights Many of the reform-minded Progressives were women who joined agencies like the National Conference of Social Work and the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. While these organizations successfully lobbied on the state level, women realized that they could influence Congress more directly if they had the vote, and they organized a strong movement for female suffrage, based on the idea that women would use political power to benefit the disadvantaged. In 1890 the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed and worked effectively to have the Nineteenth Amendment passed in 1920. E. A Ferment of Ideas: Challenging the Status Quo The Progressives were pragmatists, as defined by the philosopher William James. For them, the value of an idea was measured by the action it inspired. Pragmatism rejected the belief that there were immutable laws governing society. John Dewey, a Progressive educator, developed educational techniques that stressed personal growth, free inquiry, and individual creativity. Thorstein Veblen and Richard Ely attacked classical economic theory from a Pragmatic viewpoint. Another major intellectual movement, Socialism, also gained increased support during the era. A Socialist party was formed in 1901 and won a number of local elections. It ran Eugene Debs for president in 1912, and polled over a million votes. REFORM IN THE CITIES AND STATES Progressives were strongest in the urban area, where they took control of local levels of government in order to solve social problems. During the Progressive era, government power increased, even on the federal level, and the bureaucracy grew, because Progressives believed that government by experts was the solution to most problems. A. Interest Groups and the Decline of Popular Politics The percentage of people who voted declined rapidly in the Progressive era, partly because interest groups, such as labor unions and professional associations, were so effective in getting favorable legislation by lobbying efforts. B. Reform in the Cities The urban reform leagues, which existed as little more than debating clubs in the 1880s, became more active after 1900. Copying business methods, they gave greater efficiency to urban government by forming a professional, nonpolitical civil service. In many cities, starting in 1900 with Galveston, Texas, appointed commissioners took the place of elected officials. The city manager idea also spread. In many cities such as Cleveland, where the mayor was elected, this era was famous for characters such as reform mayors Tom Johnson, who made Cleveland the best-governed city in the nation, and “Golden Rule” Jones of Toledo. C. Action in the States Reformers realized that certain problems had to be solved on the state level, and state after state created regulatory commissions to investigate most aspects of economic life. As in the case of the railroads, the commissions sometimes damaged the industry they were supposed to regulate. On the political level, Progressives added three new features to American government: the initiative, the referendum, and the recall. In 1917, Progressives celebrated passage of the Seventeenth Amendment, which provides for the direct election of U.S. senators. Just as there were famous reform mayors, so were there reform governors. The most notable was Robert La Follette, whose “Wisconsin Idea” was a comprehensive program of reform that allied government with the academic community. THE REPUBLICAN ROOSEVELT Theodore Roosevelt, often defying convention, as when he invited Booker T. Washington to the White House, brought an exuberance to the presidency and surrounded himself with able associates. A. Busting the Trusts Roosevelt believed that trusts could sometimes be good, but he intended to attack those he considered bad. In 1902 the government brought antitrust cases against the Northern Securities Company, a railroad holding company owned by Morgan and Rockefeller, and other companies. In 1904 Northern Securities was dissolved. The case established Roosevelt as a “trust-buster,” but the title is undeserved. Compared with Taft, Roosevelt started relatively few antitrust suits. B. “Square Deal” in the Coalfields In 1902 a prolonged strike called by the United Mine Workers against the coal mine operators in Pennsylvania threatened the entire economy. Roosevelt summoned both sides to the White House, and when the companies balked at a settlement, Roosevelt threatened to use the army to seize the mines. The companies gave in. In this case, as in others, Roosevelt saw his role as that of a broker between contending interests. ROOSEVELT PROGRESSIVISM AT ITS HEIGHT Roosevelt easily won the election of 1904, and immediately embarked on a progressive reform program. A. Regulating the Railroads Roosevelt addressed the complaints of farmers by passage of the Hepburn Act, which strengthened the authority of the Interstate Commerce Commission to set rates. B. Cleaning Up Food and Drugs The publication of The Jungle by Upton Sinclair in 1906 shocked the nation into realizing how unsanitary the meat-packing industry was. After reading the book, Roosevelt pushed Congress to pass the Meat Inspection Act and other legislation to regulate patent medicines. C. Conserving the Land Roosevelt, always interested in conservation, almost quadrupled the number of acres protected by the federal government. He agitated for even more pro-labor legislation as his term came to an end. He had promised not to run again in 1908 and tapped William Taft as his successor. THE ORDEAL OF WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT Taft was too lazy and too much an introvert to be a successful president. He had been an able administrator and was used to settling problems quietly. In addition, the conservative wing of the Republican party, cowed by Roosevelt, began to reassert itself. A. Party Insurgency The issue that most divided the progressive and conservative wings of the Republican party was the tariff. It was generally agreed that the rates set by the Dingley Tariff had to be lowered, but Progressives wanted deep cuts, especially in those products produced by the large trusts. Taft eventually sided with the conservatives, who passed the Payne-Aldrich Act of 1909. The Progressives broke with Taft and began to look forward to electing Roosevelt in 1912. B. The Ballinger-Pinchot Affair Taft further antagonized Progressives and Roosevelt when he fired Gifford Pinchot, a leading conservationist, because of his insubordination toward Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger, whom Pinchot accused of selling public lands to friends. C. Taft Alienates the Progressives Even when Taft attempted to support progressive measures, such as his successful effort to strengthen the ICC by the Mann-Elkins Act of 1910, he found himself deserted by the Progressives whenever he had to make even minor concessions for conservative votes. In the 1910 congressional elections, Taft attacked the Progressives, weakening the entire Republican party and allowing the Democrats to gain control of Congress. Taft worked well with the Democratic Congress; together, they passed legislation protecting laborers and creating an income tax (the Sixteenth Amendment). Taft also pushed ahead with antitrust suits, including one against a merger that Roosevelt had approved. Roosevelt and Taft began to attack one another publicly, and in 1912 Roosevelt announced his candidacy for president. D. Differing Philosophies in the Election of 1912 Although Taft was nominated by the Republican party, he had no chance of victory. Roosevelt ran as the candidate of the Progressive (or “Bull Moose”) party, and Woodrow Wilson was nominated by the Democrats. Roosevelt campaigned on the promise of a “New Nationalism,” in which the federal government would actively regulate and stimulate the economy and in which wasteful competition would be replaced by efficiency. Wilson promised a “New Freedom,” in which big business and the government would be restrained so that the individual could forge ahead on his own. Because the Republican vote was divided, the Democrats won both the White House and Capitol Hill. WOODROW WILSON’S NEW FREEDOM Woodrow Wilson reached the White House through an academic rather than a political career. He had been a history professor and the president of Princeton University before being elected governor of New Jersey. A progressive, an intellectual, stubborn and self-righteous, and an inspiring orator, Wilson was one of America’s most effective presidents. A. The New Freedom in Action Wilson led Congress in the passage of several important measures. The Underwood Tariff of 1913 cut duties substantially; the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 reformed the banking system and gave the United States a stable but flexible currency, and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 outlawed unfair trade practices and limited the use of court injunctions against labor unions. In 1914, the Federal Trade Commission was established to supervise business. With this much accomplished, Wilson abruptly announced that the “New Freedom” had been achieved in November 1914. B. Wilson Moves Toward the New Nationalism Wilson retreated from reform because he was distracted by the outbreak of war in Europe, because he needed conservative southern support, and because the Republicans seemed to make gains by attacking Wilson’s programs. In 1916, Wilson, who wished to be reelected, again pushed progressive reforms. He succeeded in helping farmers with the Federal Farm Loan Act. He intervened in strikes on the side of the workers. He tried to ban child labor. He increased income taxes on the rich. He gave his support to female suffrage. In blending elements of the New Freedom with elements of the New Nationalism, Wilson adopted a pragmatic approach to reform and won a close election in 1916. CONCLUSION: THE FRUITS OF PROGRESSIVISM The Progressive era lasted little more than the decade between 1906 and 1916, but it had a permanent influence on American life. The Progressives energized government at all levels to correct glaring inequities and brought intelligent planning to the work of reform. It was confidently expected that a benevolent bureaucracy would continue to manage American life in an enlightened way, but the slaughter and madness of World War I ended the optimism upon which Progressivism had been based.