6th amendment NOTES - WCS-AmericanGovernment

advertisement

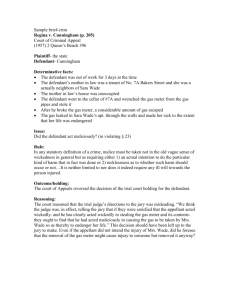

1. Explain the 6th amendment a. Explain a speedy trial i. Can’t be too speedy 1. Arkansas case thrown out because it only took 45 minutes ii. Klopfer v. North Carolina (1967) 1. Extends 6th amendment to the States (14th amendment) iii. Barker v. Wingo (1972) 1. Speedy Criteria a. The length of the delay b. Reasons c. Has the delay harmed the defendant d. Did the defendant ask for the delay iv. Explain the Speedy Trial Act of 1974 1. Speedy = Usually within 100 days of being arrested a. Exceptions = mental tests / witnesses are ill b. Explain a public trial i. Public = Coverage from media must not infringe on defendant’s rights 1. Judge’s decision 2. OJ Simpson case / TV coverage??? 3. Right is to the defendant not the media ii. Estes v. Texas (1965) 1. Case dismissed because TV cameras made the trial a “circus-like” event iii. Chandler v. Florida (1981) 1. Cameras are constitutional, just don’t get crazy c. Explain a trial by jury i. Defendant has the right to: 1. Jury trial, chosen from “the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law.” a. Williams v. Florida (1970) i. Facts of the Case: In 1967, the state of Florida passed legislation to allow six-member juries in criminal cases. Johnny Williams was tried and convicted for robbery by such a jury. Williams, lost in a Florida appellate court; he appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. ii. Question: Did a trial by jury of less than 12 persons violate the Sixth Amendment? iii. Conclusion: The Court held that "the 12-man [jury] requirement cannot be regarded as an indispensable component of the Sixth Amendment." The Court found that the purpose of the jury trial was "to prevent oppression by the Government," and that the performance of this role was not dependent on the particular number of people on the jury. The Court concluded that "the fact that the jury at common law was composed of precisely 12 is a historical accident, unnecessary to effect the purposes of the jury system and wholly without significance 'except to mystics.'" b. Burch v. Louisiana (1979) i. Facts of the Case: Burch was found guilty by a nonunanimous six-member jury of showing obscene d. films. The court imposed a suspended prison sentence of two consecutive seven- month terms and fined him $1,000. ii. Question: Does a conviction by a nonunanimous sixmember jury in a state criminal trial for a nonpetty offense violate the accused's right to a trial by jury as protected by the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments? iii. Conclusion: The Court found that convictions by the nonunanimous six-member jury violated the Constitution. Tracing the development of the Court's considerations of this issue, Justice Rehnquist indicated that Burch's case sat at the "intersection of our decisions concerning jury size and unanimity." Rehnquist relied on the Court's holding in Ballew v. Georgia (1978) and the practices in several of the states to find against convictions by nonunanimous juries of six members. Only two of the states that used six-member juries in trials for petty offenses allowed verdicts to be less than unanimous. This "near uniform judgment of the Nation" of the inappropriateness of this jury arrangement, argued Rehnquist, provided the Court with a "useful guide" in determining constitutionally allowable jury practices. c. Strauder v. West Virginia (1880) i. Jury = “drawn from a fair cross section of the community” d. Taylor v. Louisiana (1975) i. Cannot discriminate against groups in the community e. Miller-El v. Dretke (2005) i. Cannot discriminate by “the pigmentation of skin, the accident of birth, or the choice of religion” ii. "selection process was replete with evidence that prosecutors were selecting and rejecting potential jurors because of race." -- black f. Explain how to serve as a juror 2. “Change of venue” a. People are prejudice towards you 3. May waive a jury trial a. One Lot Emerald Cut Stones and One Ring v. United States (1972) i. Judge can force jury trial even if defendant waives the right b. Define bench trial i. Judge alone hears the case Explain the right to an adequate defense i. Defendant has the right: 1. To be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation 2. To be confronted with the witnesses against him, and question them in open court 3. To have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor (that is, favorable witnesses can be subpoenaed, or forced to attend) 4. To have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense ii. Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) 1. A defendant must have the attorney if he/she wants one (even if you cannot afford one) 2. Usually a lawyer from the local community or a private legal aid association that provides counsel 3. Now, more and more come from local tax dollars iii. Confrontation Clause 1. Pointer v. Texas (1965) a. Petitioner was arrested and brought before a state judge for preliminary hearing on a robbery charge. The complaining witness testified but petitioner, who had no counsel, did not cross-examine. Petitioner was later indicted and tried. The witness had moved to another State, and the transcript of his testimony at the hearing was introduced over petitioner's objections that he was denied the right of confrontation. He was convicted and the highest state court affirmed. b. You have the right to be confronted with the witnesses against him, and question them in open court 2. Smith vs. Illinois (1968) – Confrontation Clause a. Addressed the issue of whether or not the state could introduce as evidence, statements obtained from an undercover police informant, against a defendant charged with selling drugs. The state would not produce the witness (undercover police informant) in person because it said that revealing his identity would undermine the secretive nature and strategies used by the police department. The defendant claimed that his 6th Amendment Confrontation Clause right to confront the witness had been violated in his trial and that the conviction should be thrown out. The Court agreed with the defendant. The right to cross-examine a witness is absolute. 3. Bruton vs. United States (1968) a. In this case, the two defendants, Bruton and Evans, were charged with armed postal robbery. During the trial, a postal inspector said that Evans had confessed to him that both he and Bruton had committed the crime. Neither Evans nor Bruton took the stand in the trial. When the jury was deliberating its decision, the judge instructed them that the hearsay testimony of the postal inspector could not be used as evidence against Bruton, and they should disregard this statement when making their decision. He also told them that the statement could be used against Evans himself. The principle being addressed here is that Bruton's defense attorney could not cross-examine the witness, Evans, who allegedly made the statement, because Evans was not going to take the stand! This violated Bruton's 6th Amendment Confrontation Clause right to cross-examine the witness! The first court found Evans and Bruton guilty. The Supreme Court ruled that the conviction against Bruton had to be thrown out because his Confrontation Clause right to cross-examine the witness had been violated. Later, by the way, the conviction against Evans was thrown as well, based on other violations. This was an important case because it is a favorite trick of prosecutors to conduct a joint trial and use witnesses’ statements against each other. The statements can't be used by the jury if the witnesses aren't taking the stand, but the jury heard them anyway and the statements might influence them even though they are told to disregard them. Although there are exceptions, this ruling has eliminated many joint trials. 4. Washington v. Texas (1967) 1. Petitioner and another were charged with a fatal shooting. Petitioner's alleged co-participant was tried first and convicted of murder. At petitioner's trial for the same murder, he sought to secure his co-participant's testimony, which would have been vital for his defense. On the basis of two Texas statutes which, at the time of trial, prevented a participant accused of a crime from testifying for his coparticipant (but not for the prosecution), the judge sustained the State's objection to the coparticipant's testimony. Petitioner's conviction ensued, and was upheld on appeal. 2. Unconstitutional to deny the ability to obtain witnesses in his favor iv. Escobedo v. Illinois (1964) 1. Danny Escobedo, picked up for questioning in his brother-inlaws murder, asked numerous times for an attorney. Police denied requests, even though his lawyer was in the police station and was trying to see him. Escobedo made numerous damaging statements. 2. Unconstitutional (freed then from jail) i. Became a drifter. Arrested in 2001 for probation violation and was a suspect in a 1981 stabbing murder. v. Scott vs. Illinois (1979) 1. A case involving a defendant who was convicted of shoplifting and fined $50 in a bench trial. The applicable Illinois law stated that the maximum penalty for the crime was a $500 fine or one year in jail, or both. The defendant appealed the case claiming that his 6th Amendment right to counsel had been violated because he did not have personal means to hire an attorney and the court had not appointed one for him. The Court disagreed with the defendant. Before this case, the Court's rule had been that if imprisonment was even a possible punishment, the defendant was entitled to appointed counsel. In this case, the Court ruled that just the fact that imprisonment was a possible punishment alone did not require that an attorney be appointed. Instead, the Court said that imprisonment must be the actual sentence laid down in order to require the court to appoint an attorney for the defendant. vi. Halbert v. Michigan (2005) Facts of the Case Halbert pleaded no contest in a Michigan court to two counts of criminal sexual conduct. The day after Halbert's sentence was imposed, Halbert moved to withdraw his plea. The trial court denied the motion and told Halbert the property remedy for his complaint was the state appellate court. Michigan required a defendant convicted on a guilty or no contest plea to apply for leave of appeal to the state appellate court. Halbert asked the trial court twice to appoint counsel to help him with his application. The trial court refused. Without counsel, Halbert still applied for leave to appeal, which the court of appeals denied. The state supreme court also denied Halbert's application for leave to appeal to that court. Question Did the due process and equal protection clauses require the appointment of counsel for defendants, convicted on their pleas, who sought access to a Michigan appellate court? Conclusion Yes. In a 6-3 opinion delivered by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court held that the due process and equal protection clauses required Michigan to provide counsel for defendants who wanted to appeal to the state appellate court. The Court reasoned that if indigent defendants convicted on their pleas did not have counsel to guide them through Michigan's complex appellate process, their right to appeal would not be meaningful. vii. Insanity Defense A defense asserted by an accused in a criminal prosecution to avoid liability for the commission of a crime because, at the time of the crime, the person did not appreciate the nature or quality or wrongfulness of the acts. HISTORY: "Complete madness" was first established as a defense to criminal charges by the common-law courts in late-thirteenth-century England. By the eighteenth century, the complete madness definition had evolved into the "wild beast" test. Under that test, the insanity defense was available to a person who was "totally deprived of his understanding and memory so as not to know what he [was] doing, no more than an infant, a brute, or a wild beast" 1. Queen v. M'Naghten (1863) a. FACTS: i. M’Naghten believed he was persecuted by Tories, and he sought to assassinate Prime Minister Robert Peel. Failing to accurately identify Peel from behind, he inadvertently shot the Prime Minister’s secretary, Edward Drummond, who died several weeks later. M’Naghten was found not guilty on the grounds of insanity. b. ISSUE: i. What is the proper standard for insanity? What questions should be posed to the jury, and how should the jury be instructed? c. M’Naghten Rule (“Right or Wrong” test) i. To establish a defense on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from a disease of the mind, as not to 2. 3. 4. 5. know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was right or wrong. Durham Rule (1954) a. The rule, as stated in the court's decision, held that "an accused is not criminally responsible if his unlawful act was the product of mental disease." It required a jury's determination that the accused was suffering from a mental disease and that there was a causal relationship between the disease and the act. Because of difficulties in its implementation, the Durham rule was rejected by the same court in the 1972 case United States v. Brawner United States v. Brawner (1972) a. The Court decided to accept the American Law Institute definition of insanity as defined below for trials after this date. A person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law. b. A mental disease or defect includes any abnormal condition of the mind which substantially affects mental or emotional processes and substantially impairs behavior controls. Ake v. Oklahoma (1985) a. FACTS: i. An indigent defendant was charged with first-degree murder and firing a gun with intent to kill. The trial court judge ordered a competency evaluation due to his odd behavior at the arraignment four months after commission of the crime. A psychiatrist initially determined he was incompetent to stand trial, but reversed his opinion six weeks later, after the defendant had been medicated with large doses of an anti-psychotic drug to control symptoms of his chronic illness. Defendant's pretrial request for a psychiatric evaluation at state expense was denied in spite of the fact that insanity was the sole defense to be asserted. Defendant was convicted and, at the guilt phase of the trial, psychiatric evidence as to his dangerousness was admitted. No testimony as to his sanity at the time of the offense was presented. At sentencing, the State requested and received the death penalty, relying on evidence of the defendant's future dangerousness. The defendant was unable to rebut this expert testimony or to present mitigating evidence. b. RESULT: i. The U.S. Supreme Court announced the federal constitutional right of an indigent criminal defendant to receive, at state expense, the assistance of a psychiatric expert. Insanity Defense Act (1985) a. The Insanity Defense Reform Act of 1984 (Act) was the first comprehensive U.S. federal law governing the insanity defense and the disposition of individuals suffering from a mental disease or defect who are involved in the criminal justice system. b. Some of the important provisions of the Act are: i. The Act significantly modified the standard for insanity previously applied in the federal courts. ii. Shifted the burden of proof on the defendant to establish the insanity defense by clear and convincing evidence. iii. Eliminated the defense of diminished capacity. iv. Limited the scope of expert testimony on ultimate legal issues. v. Provided for federal commitment of persons who become insane after having been found guilty or while serving a federal prison sentence. vi. Created a special verdict of "not guilty only by reason of insanity," which triggers a commitment proceeding.