Someone Else’s Assignor Can Estop You:

When Consultants Prevent Patent Validity Challenges

By Jeffrey I. D. Lewis and Christopher M. Schmitt

Messrs. Lewis and Schmitt are a partner and associate, respectively, in

the firm of Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP, New York City. The

views expressed are solely those of the authors and should not be

attributed to either one of them individually or to any client or

institution. All rights reserved © 2014.

Imagine hiring a consultant who designs a process, only to find that the process infringes

a patent invented by the same consultant for someone else. Imagine how much worse it would

be if the involvement of this consultant meant that you could not challenge the validity of that

patent. That is the rude surprise some are facing.

Often a consultant is hired precisely for his or her prior experience and past

accomplishments; the object is to hire someone who has “been there, done that” and who can do

it again. But if this consultant was too close, serving as a key employee more than as a

consultant, then the assignor estoppel doctrine can bar any argument that the consultant’s prior

patents are invalid. One of the authors recently litigated a case on the subject, and the results are

both instructive and represent a broadening of the doctrine.

1.

ASSIGNOR ESTOPPEL

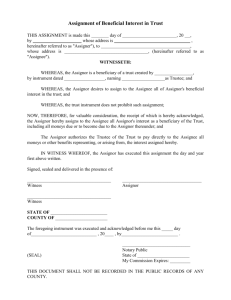

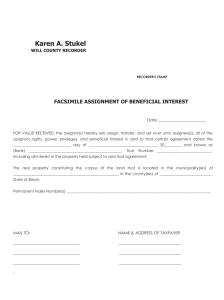

Assignor estoppel “is an equitable doctrine that prevents one who has assigned the rights

to a patent (or patent application) from later contending that what was assigned is a nullity.”

Diamond Scientific Co. v. Ambico, Inc., 848 F.2d 1220, 1224 (Fed. Cir. 1988). The animating

concept is simple and sensible – “an assignor should not be permitted to sell something and later

to assert that what was sold is worthless, all to the detriment of the assignee.” Id.

6702740v.6

In order to accomplish its equitable purpose, the doctrine “also operates to bar other

parties in privity with the assignor, such as a corporation founded by the assignor” (id.), from

challenging the assigned patent. Although there are not many cases invoking assignor estoppel,

decisions have extended the doctrine to inventors who became a new employer’s highlyintegrated employee, something more than a “mere employee.” As the Federal Circuit has

explained, where

an inventor assigns his invention to his employer company A and

leaves to join company B, whether company B is in privity and

thus bound by the doctrine will depend on the equities dictated by

the relationship between the inventor and company B in light of

the act of infringement. The closer that relationship, the more the

equities will favor applying the doctrine to company B.

Shamrock Technologies, Inc. v. Medical Sterilization, Inc., 903 F.2d 789, 793 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

“[F]or a finding of privity, what is significant is whether the ultimate infringer availed itself of

the inventor’s knowledge and assistance to conduct infringement.” HWB, Inc. v. Braner, Inc.,

869 F. Supp. 579, 581 (N.D. Ill. 1994), citing Intel Corp. v. U.S. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 946 F.2d

821, 839 (Fed. Cir. 1991). Whether privity exists is a fact-specific inquiry derived from both the

“direct and indirect” contacts between the inventor and the accused infringer. Intel, 946 F.2d at

838. At base, determining privity, “like the doctrine of assignor estoppel itself, is determined

upon a balance of the equities.” Shamrock, 903 F.2d at 793.

Although a close relationship theoretically could exist in any business setting, assignor

estoppel cases have generally focused on the traditional, paid employee. Specifically, this has

included employees that have a heightened interest in the success of an infringing product at

their new employers (the accused infringers), such as by earning royalties or profit sharing, or

even an ownership/shareholder interest. See, e.g., Diamond Scientific, 848 F.2d at 1224

(assignor-inventor left plaintiff to form defendant); Shamrock, 903 F.2d at 794 (assignor2

6702740v.6

inventor worked for defendant as Vice President for operations, owned 50,000 shares in

defendant, was hired specifically for the infringement, oversaw the building of new facilities for

the infringement, and participated in decisions to infringe); Intel, 946 F.2d at 837-38 (assignorinventor was president and chief executive of defendant and owned 40% of shares making him

largest single shareholder); Carroll Touch, Inc. v. Electro Mech. Sys., Inc., 15 F.3d 1573, 1579

(Fed. Cir. 1993) (assignor-inventor was founder, president, principal executive officer, and

owned stock in defendant corporation); Mentor Graphics Corp. v. Quickturn Design Systems,

Inc., 150 F.3d 1374, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (applying privity to find assignor estoppel even as to

later-acquired subsidiary where corporate assignor owned stock, shared personnel and had

control over party). Cf HWB, Inc., 869 F. Supp. at 582 (since assignor-inventor “was not hired

… to initiate the alleged infringement operations, to oversee the construction of facilities … and

[defendant] did not avail itself of [his] knowledge and assistance in order to manufacture the

infringing product,” estoppel not applied); Earth Resources Corp. v. United States, 44 Fed. Cl.

274, 52 U.S.P.Q.2d 1545 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (no assignor estoppel where there was neither a

financial interest in infringement nor “significant influence or control over” defendant).

“‘If the estopped assignor enters into business [with] others, who derive from him their

knowledge of the patented process or machine[, and,] availing themselves of this knowledge and

assistance, enter with him upon a manufacture infringing the patent which he has assigned, they

are bound by his estoppel.’” HWB, 869 F. Supp. at 581 (quoting Mellor v. Carroll, 141 F. 992,

993-994 (C.C.D. Mass. 1905)). However, an emerging body of law challenges this bright-line

standard by extending the doctrine to more informal business relationships, particularly

consultants.

3

6702740v.6

A.

The Consultant-Assignor With An Interest

In Designing Health, Inc. v. Erasmus, the court considered privity and assignor estoppel

on a complex but interesting fact pattern that highlights many of the key issues underlying the

estoppel analysis. 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25951 (C.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2001). Erasmus worked

with the plaintiffs, and as part of his consulting he formulated a pet food supplement for

Designing Health, designed the manufacturing process, and participated in promotional activities

for the product. Id. at *5. Erasmus assigned to plaintiff patent applications where he was a listed

as a co-inventor for Designing Health. As part of his compensation, Erasmus received 40,000

shares of stock in Designing Health. Id. at *5-7. Two patents issued covering the pet food

supplement invention naming Erasmus as a co-inventor. Id.

Erasmus also was involved with designing infringing pet foods for the defendants and

received an 8% royalty on the sale of those infringing products. Id. at *5, *9-10. Designing

Health sued, and the court indicated that it was inclined to apply assignor estoppel against at

least Erasmus. Id. at *18 (“Having received value in exchange for his inventions and for the

patent applications already pending, Erasmus and those in privity cannot now challenge the

validity of the patents issued on those same inventions.”).

As part of their defenses, the defendants had alleged that the inventors of the patents-insuit engaged in inequitable conduct. This normally would bar the patent owner from relying on

an equitable defense like assignor estoppel, if proven, because of “unclean hands.” But, the

court was concerned that Erasmus not profit from his possible involvement in any inequitable

conduct since ultimately the application of unclean hands would benefit Erasmus and the other

defendants. Accordingly, the court applied assignor estoppel against Erasmus to bar him from

challenging patent validity. Id. at 20-21. Moreover, given the evidence of privity and the

4

6702740v.6

closeness of the relationship between the other defendants and Erasmus – such as Erasmus’

direct involvement in making the accused pet foods, and the royalty obligations to Erasmus by

the other defendants – the court granted summary judgment of assignor estoppel against the

remaining defendants as well. Id. at *22-23 (“Defendants availed themselves of Erasmus’

knowledge and assistance in making those products and … Erasmus played a direct role in the

creation of the allegedly infringing products.”).

The Designing Health case, like many others, relied in part on the actions of the assignorinventor and his significant continuing interest (e.g., royalties on infringing sales) to find privity.

See, e.g., Intel Corp., 946 F.2d at 839 (finding privity between an inventor and a corporation in

light of a “continuous involvement in a joint development program,” including a substantial

financial commitment); Mentor Graphics, 150 F.3d at 1379 (extending privity to a company

under “considerable control” by another corporation, already estopped). But these cases all

relied upon the consultant being economically invested in the infringement as a basis for finding

assignor estoppel.

B.

The Consultant-Assignor Without An Interest

The case of BASF Corp. v. Aristo, Inc., 872 F. Supp. 2d 758, 775 (N.D. Ind. 2012)

(argued by one of the authors), considered a less interested consultant. BASF’s retired

employee, who had worked in coatings and invented several patents for BASF and its

predecessor prior to retirement, started consulting for defendant Aristo and was asked to design a

coating process as well as the machine for conducting that process. Eventually, BASF sued

Aristo for patent infringement on a patent where the consultant was the first named inventor, and

BASF eventually named the consultant as a co-defendant. Aristo and the consultant argued that

the patent was invalid, and BASF asserted assignor estoppel.

5

6702740v.6

Aristo asserted that the inventor was only a “mere consultant” – a reference to the

exception for “mere employees” no doubt – but the undisputed facts indicated that the infringing

corporation “availed itself” of the inventor’s “knowledge and assistance.” Id. at 776, 775. For

instance, the inventor developed the infringing coater, developed its specifications, oversaw its

fabrication, drafted its operating procedures, and taught operators how to use it. The consultant’s

tasks “were directed towards the allegedly infringing conduct” and thus Aristo fully “availed

itself” of the assignor-inventor. Id. at 775.

Even though this consultant did not have an ownership or managerial interest in Aristo,

the court still found a sufficiently close relationship to impute the assignor estoppel doctrine to

the infringing corporation. Id. The court did not consider the lack of royalties or ownership an

impediment to applying assignor estoppel. Instead, the court looked to the inventor’s

participation “in the design, manufacture, and operation” of the allegedly infringing machine and

process. Id. at 776. From that vantage, it was persuasive that the consultant was instrumental to

the infringement – although Aristo “had some of the know-how” to create the coating machine,

“[i]t needed [the consultant] to fill in the gaps to build the machine.” Id. at 775. In light of this

“significant role,” id. at 776, privity was warranted since the consultant operated as something

more than a “mere” participant or advisor.

2.

Developing Expansion of the Doctrine

This decision was relied upon in Brocade Communications Systems v. A10 Networks,

Inc., 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84879 (N.D. Cal. June 18, 2012). Applying BASF, the court

concluded that whether an inventor was “initially a part-time consultant” was “immaterial” as

“[a]n inventor/assignor need not be a full-time employee for privity to apply.” Id. at *30.

6

6702740v.6

In Brocade, one of the co-founders of the plaintiff corporation, Foundry, secretly began a

competing venture while still employed there. Id. at *10. He eventually left Foundry to further

his competing venture, A10 Networks, taking several of Foundry’s employees to the new entity,

and these employees, in turn, brought with them Foundry’s intellectual property. Id. Jalan was

one of those who moved to A10 Networks, although he initially was “a part-time, unpaid

consultant.” Id. at *8, *20. Before moving to A10 Networks, Jalan had assigned three patents to

Foundry, and when A10 Networks eventually developed a competing product Foundry sued on

Jalan’s assigned patents. Id. at *10-11. The relevant issue was whether the relationship between

A10 Networks and Jalan was sufficient to apply the doctrine of assignor estoppel, and the court

concluded that it was.

Instead of affording weight to Jalan’s initial role as an unpaid, part-time consultant, the

court looked to the relevant factors set out in Shamrock for “useful, although not dispositive

guidance”:

(1) the assignor/inventor was a high level employee at his new employer; (2) the

assignor/inventor owned shares in his new employer; (3) as soon as the

assignor/inventor was hired, the new employer built facilities for performing the

infringing activity; (4) the assignor/inventor oversaw the design and construction

of those facilities; (5) the assignor/inventor was hired in part to start up the

infringing operations; (6) the decision to begin the infringing operation was made

jointly by the assignor/inventor and the president of his new employer; (7) the

infringing product reached the market with reasonable speed after hiring the

assignor/inventor; and (8) the assignor/inventor was in charge of his new

employer’s infringing operations.

Id. at *19.

Applying these factors, the Brocade court looked beyond the assignor-inventor’s initial

role as a part-time, unpaid consultant, but instead focused on his “leadership role” in developing

the infringing product and the overall “close relationship” between him and the company. Id. at

*20. As in BASF, the central consideration was whether “‘the ultimate infringer availed itself of

7

6702740v.6

the inventor’s knowledge and assistance to conduct infringement.’” Id. at *30 (citation omitted).

Because “as a part-time consultant Jalan participated in ‘design discussions’ and ‘code reviews’

and ‘provided some input on the design framework’ of the [infringing] device,” id. at *31, he

was found to have a sufficient leadership role that the company was estopped from arguing

patent invalidity, notwithstanding his initial title.

3.

Practical Take Away

While some might argue that these cases reach a sensible, equitable result on their facts,

they also present a practical problem: using a consultant could hamstring a corporation’s

defenses in patent litigation. Of course, it is the consultant’s knowledge that makes them

attractive to hire and even sometimes necessary, but it is this same technical expertise that can

make them ultimately a liability. There are, however, a few basic steps that can mitigate this risk

and help all to sleep a bit more soundly.

It always helps to ask questions and be aware of the potential for such conflicts before

they develop. In each of the cases detailed above the defendant corporation had the consultant’s

patent history available, but they did not use it as a cautionary guide to the consultant’s work.

When hiring a consultant it would be advisable to consider the consultant’s issued patents, and

perhaps review the consultant’s patents when clearances are considered for the consultant’s work

before it is commercially developed. In this way, any issues can be identified before litigation.

But it is not just the consultant’s patents that should be considered. As with any hire,

care must be taken if the person is a competitor’s former employee. Here too, a careful review of

the consultant’s qualifications prior to hiring can avoid a future problem.

It also is useful to have the consultant work with others of similar expertise who can

oversee the consultant’s work. In the cases discussed above, each consultant was retained

8

6702740v.6

precisely because of the specific expertise from working directly on or with the patented

technology and given significant authority to recreate what they had done elsewhere. In BASF,

the defendant corporation “availed itself” of the inventor/consultant’s knowledge to “fill in the

gaps” by importing the expertise acquired from the earlier patent for a coating process. 872 F.

Supp. 2d at 775. The defendant corporation selected that particular consultant precisely

“because of his expertise designing coaters,” specifically informing him that it was looking “to

develop an advanced coating method and machine,” which also is what the inventor/consultant

did for his prior employer-assignee (BASF). Id. at 765. Even more glaring, in Brocade the

defendant corporation was comprised of the plaintiff’s “rogue” employees who had allegedly

brought the plaintiff’s intellectual property with them to start a competing venture.

In all of the cases extending privity to consultants so far, the particular consultancies have

been highly-integrated and ongoing – nearly akin to that of an employer-employee relationship.

In BASF the court noted an “ongoing working relationship” between the consultant and the

defendant that had “continued over the course of several years” and through the years of

litigation up to the writing of the court’s opinion. 872. F. Supp. 2d at 776. In Designing Health,

the consultant-inventor’s income was tied to the company in that he was contracted to receive an

ongoing 8% royalty on those allegedly infringing products with free reign to design the pet food.

And, even more compelling, the consultant in Brocade received free health insurance, was later

elevated to chief technology officer of the defendant corporation – a supervisory role – and

eventually amassed more than a million shares and options, a “considerable, albeit not

controlling,” share. 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS at *27, *20, *23-24. Such consultants are not

merely being paid for advice, but are integrated into the fabric of the company in some fashion

with operational autonomy. In other words, where consultants begin to look more like

9

6702740v.6

employees, particularly supervisory employees, courts are more likely to treat them as such for

the purposes of assignor estoppel.

Consultants who are given decision-making authority will be treated by the courts like an

employee, and will be analyzed according to the same parameters for privity and estoppel. To

the extent those sorts of deep, ongoing ties can be avoided or reduced, the equitable case for

privity will be lessened and the hirer protected. The word to the wise, therefore, is caution –

beware of integrating your consultants too deeply, lest a court will treat them like one of your

own.

10

6702740v.6