File - Jared's e

advertisement

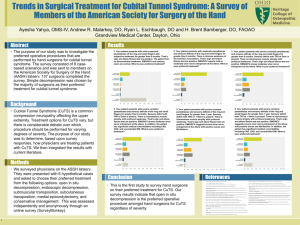

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome By: Jared Rose 6/1/2013 AT 4810: Dr. Jordan Utely, PhD,LAT,ATC Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Section 1: Introduction to the Pathology Found on the medial side of each upper extremity at the area of the elbow joint, the cubital tunnel is a pathway through joint and tissue for the ulnar nerve as it runs along the medial side of the elbow joint. <PHOTO 1: CUBITAL TUNNEL> ("Cubital tunnel syndrome," 2009). Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) is entrapment, compression, or lesions of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. Incidence of the Pathology Of all entrapment neuropathies of the body, entrapment of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel is the most common. Of all compressive nerve lesion injuries, cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common. (Nakao, Takayama, & Toyama, 2001). Cubital tunnel syndrome is reported to affect 24.5 of every 100,000 people. (Trehan, Parziale, & Akelman, 2012) Of those that are afflicted with this syndrome, it is 3-8 times more likely to be a man than a women (Verheyden, 2013). Certain occupations and hobbies have been linked to increase risk of CTS. It’s been found that up to 42% of workers using vibrating tools end up with the syndrome. Also those who spend prolonged time in elbow flexion (holding a phone to the ear) fit in this category. In particular, those that maintain long periods of elbow flexion while also resting the elbow on a hard surface have increased chances of this syndrome (Cutts, 2007). Another group that is of increased risk is baseball players. It has been found that the part of the throwing cycle that involves extreme flexion (late cocking, early acceleration) is “strongly suggestive” of cubital tunnel syndrome. (Cutts, 2007). Etiology CTS can be caused by constricting fascial bands, subluxation of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle, bony spurs, hypertrophied synovium, tumors, or direct compression. Occupational activities may aggravate cubital tunnel syndrome secondary to repetitive elbow flexion and extension. (Veyheyden, 2013) Section 2: Anatomy and Physiology of the Injury Anatomy With CTS the main anatomical structures involved are the ulnar nerve, the Osborne’s ligament (the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle), the medial epicondyle, the olecranon process and the MCL of the elbow. When the ulnar nerve reaches the elbow joint it runs posteriorly of the medial epicondyle and enters into the cubital tunnel. The sides of the tunnel are represented by the medial epicondyle and the olecranon process, the roof is formed by the Osborne’s ligament which spans in a fan-like manner from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon process of the ulna. The floor of the cubital tunnel is formed by the posterior ligament of the MCL of the elbow (Wheeless, 2012). <PHOTO 2: CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME ANATOMY> (Trehan, Parziale, & Akelman, 2012) Physiology The most common physiological cause of CTS is prolonged extreme elbow flexion. When the elbow is severely flexed, space in the cubital tunnel is decreased by 55%. With this space decrease the tunnel changes from a spherical shape to an elliptical shape increasing intraneural pressure 20-fold. As a result, the extra strain and pressure can irritate the ulnar nerve and lead to CTS (Trehan, Parziale, & Akelman, 2012). Section 3: Evaluation of the Injury Signs and Symptoms The first reported symptom from patients is sensory loss in the pinky finger and the medial side of the ring finger when in anatomical position. The affected hand may also be reported as being clumsy. Discomfort and pain may also be reported in the area of the cubital tunnel. In prolonged cases there may also be wasting of the small muscles of the hand and ulnar muscle of the forearm. Signs that an examiner could look for include: clawing of the ring and pinky finger in prolonged cases and valgus deformity associated with olecranon fracture. Special Tests Ulnar Nerve Compression test: This test has a sensitivity of 89% when performed alone. To perform this test the patient should be standing. Passively flex the patients arm into approximately 20 degrees flexion. From behind the patient palpate the medial epicondyle and move laterally feeling for the groove between the olecranon process and the medial epicondyle. This is the location of the ulnar nerve, compress firmly on the nerve for 60 seconds, then release. A positive test will reveal numbness and or tingling in the ulnar nerve distribution. <CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME VIDEO 1: ULNAR NERVE COMPRESSION TEST> (“Ulnar Nerve Compression,” ulnar nerve compression test) Elbow Flexion Test: This test has a sensitivity of 75%. To perform this test the patient should be standing, starting with arms to the side. Then have the patient actively flex both arms upward until soft end-fill is reached. Patient should then bring the wrist into complete extension and supination. Positive signs for this test will be pain, tingling or numbness in ulnar distribution. <CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME VIDEO 2: ELBOW FLEXION TEST> (Elbow Flexion Test,” elbow flexion test) Tinels Sign Test: Sensitivity 70%. With the patient sitting, stand to the lateral side, passively flex elbow to about 90 degrees while putting wrist into slight flexion stretch. Palpate ulnar nerve and tap directly on it with middle finger. Positive signs will bring tingling or numbness to ulnar distribution. <CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME VIDEO 3:TINELS SIGN TEST>(“Tinel Sign At,” tinels sign at elbow) Section 4: Associated Differential Diagnosis Medial Epicondylagia: medial epicondylagia produces some of the same symptoms involved with cubital tunnel syndrome including medial epicondyle discomfort and decreased grip strength. One test to do to rule out medial epicondylagia is to sit in front of the patient and bring their arm into approximately 90 degrees flexion and wrist into full flexion. The patient should then resist while you try to bring their wrist out of flexion and into extension, a positive sign would be sharp pain in the medial epicondyle ("Physical exam for," Physical exam for epicondylitis & differential diagnoses for elbow pain ). UCL Injury: A UCL injury can also cause medial elbow discomfort, along with ulnar nerve irritation from joint instability. Therefore symptoms could be interpreted for either injury. Because UCL injury should cause medial elbow joint instability, use of, and a negative result of the Posterolateral rotary instability test of the elbow, and moving valgus stress test will help rule out UCL injury when dealing with a cubital tunnel syndrome injury. Section 5: Prognosis and Recent Evidence Informing Best Clinical Care. Recent Evidence Informing Best Clinical Care Symptoms may be relieved without the use of surgery especially if pressure on the nerve is minimal. Simple fixes include physical therapy, changing use of certain elbow patterns, avoiding prolonged elbow flexion, wearing elbow pads and splinting the elbow at night to keep from sleeping in flexion position. (http://www.assh.org/Public/HandConditions/Pages/CubitalTunnelSyndrome.aspx). If the injury is more severe and these methods do not relieve symptoms, surgery could be needed. Two of the primary surgery types used to correct cubital tunnel syndrome are first, cubital tunnel release. This procedure is done by dissecting the cubital tunnel roof, which consists of the Osborne’s ligament, giving more space to the constricted ulnar ligament. The second surgery is ulnar nerve translation. This is for the more severe cases in which the ulnar nerve has been subluxating over the medial epicondyle. During the surgery the ulnar nerve is removed from its bony grove and placed into a new resting place in front of the medial epicondyle ("Cubital tunnel release," 2013). Prognosis With ulnar release using situ decompression it has been reported that 75-90% of patients receive good to excellent pain relief. While 7-15% do not benefit (Trehan, Parziale, & Akelman, 2012). Even as reasons for cubital tunnel syndrome vary and different surgery types are used, success rate is high. One report studied 51 people who had 7 origins of cubital tunnel syndrome using surgery as treatment. Of the 51 people, 16 reported fully restored condition, 30 people reported improved condition, while 5 reported unchanged condition (Cutts, 2007). These findings should give patients optimism when faced with this form of treatment. References Cutts, S. (2007). Cubital tunnel syndrome. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 83(975), 2831. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.047456 Finsterer, J. J. (2000). Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow due to unusual sleep position. European Journal Of Neurology, 7(1), 115-117. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00022.x Matev, B. (2003). Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. Hand Surgery, 8(1), 127-131. Matsuzaki, A. (2001). MEMBRANOUS TISSUE UNDER THE FLEXOR CARPI ULNARIS MUSCLE AS A CAUSE OF CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME. Hand Surgery, 6(2), 191-197. Nakao, Y., Takayama, S., & Toyama, Y. (2001). CUBITAL TUNNEL RELEASE WITH LIFT-TYPE ENDOSCOPIC SURGERY. Hand Surgery, 6(2), 199-203. Nikitins, M. D., Griffin, P. A., Ch'ng, S. S., & Rice, N. J. (2002). A Dynamic Anatomical Study of Ulnar Nerve Motion After Anterior Trehan, S. K., Parziale, J. R., & Akelman, E. (2012). Cubital tunnel syndrome: Diagnosis and management. Medicine & Health/Rhode Island, 95(11), Retrieved from http://www.rimed.org/medhealthri/2012-11/2012-11-349.pdf Verheyden, J. R. (2013). Cubital tunnel syndrome. Medscape Reference, Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1231663-overview Wheeless, C. (2012). Wheeless' textbook of orthopaedics. Retrieved from http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/anatomy_amp_sites_of_compression_of_cubital_t unnel Cubital tunnel syndrome. (2009). Retrieved from http://www.activemotionphysio.ca/Injuries-Conditions/Elbow/Elbow-Issues/CubitalTunnel- Syndrome/a~242/article.html Cubital tunnel release & in situ decompression. (2013). Retrieved from http://orthocarefl.com/?page_id=680 (2012, October 11). Ulnar nerve compression test [Web Video]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=Q57hifGbMYE (2012, November 30). Physical exam for epicondylitis & differential diagnoses for elbow pain [Web Video]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APqfKRBNKsQ (2011, April 22). Elbow flexion test [Web Video]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=wMIlm9SULvo (2010, November 01). Tinel's sign at elbow [Web Video]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=CCO8YHrW5S4