The Grapes of Wrath

advertisement

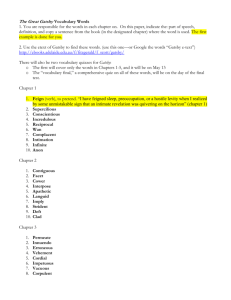

American Literature Book III Table of Contents Theodore Dreiser Edwin Arlington Robinson Carl Sandburg Sinclair Lewis Henry L. Mencken F. Scott Fitzgerald John Steinbeck Theodore Dreiser (1871-1945) American author, outstanding representative of naturalism, whose novels depict real-life subjects in a harsh light Theodore Dreiser was born in Terre Haute, Indiana in 1871. The ninth child of German immigrants, he experienced considerable poverty while a child and at the age of fifteen was forced to leave home in search of work. After briefly attending Indiana University, he found work as a reporter on the Chicago Globe. Later he worked for the St. Louis GlobeDemocrat, the St. Louis Republic and Pittsburgh Dispatch, before moving to New York where he attempted to establish himself as a novelist. He was a voracious reader, and the impact of such writers as Hawthorne, Poe, Balzac, Herbert Spencer, and Freud influenced his thought and his reaction against organized religion. Dreiser worked for the New York World before Frank Norris, who was working for Doubleday, helped Dreiser's first novel, Sister Carrie (1900), to be published. However, the owners disapproved of the novel's subject matter (the moral corruption of the heroine, Carrie Meeber) and it was not promoted and therefore sold badly. The young author felt so depressed by “a decade’s delay”—in the words of Larzer Ziff—in social recognition that he was said to have walked by the East River at the turn of the century, seriously committing suicide. Dreiser was left-oriented in his views. Dreiser continued to work as a journalist and as well as writing for mainstream newspapers such as the Saturday Evening Post, also had work published in socialist magazines such as The Call. However, unlike many of his literary friends such as Sinclair Lewis, and Jack London, he never joined the Socialist Party. In 1898 Dreiser married Sara White, a Missouri schoolteacher, but the marriage was unhappy. Dreiser separated permanently from her in 1909, but never earnestly sought a divorce. In his own life Dreiser practiced his principle that man's greatest appetite is sexual - the desire for women His strength clearly ebbing, Dreiser died of heart failure on December 28, 1945, before completing the last chapter of The Stoic. Dreiser was buried in Hollywood's Forest Lawn Cemetery on January 3, 1946. Trilogy of Desire 1. Works Sister Carrie 1900 Jennie Gerhardt 1911 An American Tragedy 1925 The Financier 1912 The Titan 1914 The Stoic (posthumously) The Genius 1915 Dreiser Looks at Russia 1928 autobiographically The Financier (1912) and The Titan (1914) about Frank Cowperwood, a powerhungry business tycoon. An American Tragedy (1925) was based on the Chester Gillette and Grace Brown murder case that had taken place in 1906. About Sister Carrie Sister Carrie, published in 1900, stands at the gateway of the new century. Theodore Dreiser based his first novel on the life of his sister Emma. In 1883 she ran away to Toronto, Canada with a married man who had stolen money from his employer. The story as told by Dreiser, about Carrie Meeber who becomes the mistress of a traveling salesman, is unapologetically told and created a scandal with its moral transgressions. The book was initially rejected by many publishers on the grounds that is was "immoral". Indeed, Harper Brothers, the first publisher to see the book, rejected it by saying it was not, "sufficiently delicate to depict without offense to the reader the continued illicit relations of the heroine". Finally Doubleday and Company published the book in order to fulfill their contract, but Frank Doubleday refused to promote the book. As a result, it sold less than seven hundred copies and Dreiser received a reputation as a naturalist-barbarian. Sister Carrie sold poorly but was redeemed by writers like Frank Norris and William Dean Howells who saw the novel as a breakthrough in American realism. However, the publication battles over Sister Carrie caused Dreiser to become depressed, so much so that his brother sent him to a sanitarium for a short while. Sister Carrie, published in 1900, is one of the best-known story of American Dream, tracing the material rise of Carrie Meeber and the tragic decline of G. W. Hurstwood. Carrie Meeber, penniless and full of the illusion of ignorance and youth, leaves her rural home to seek work in Chicago. On the train, she becomes acquainted with Charles Drouet, a salesman. In Chicago, she lives with her sister, and work for a time in a shoe factory. Meager income and terrible working condition oppress her imaginative spirit. After a period of unemployment and loneliness, she accepts Drouet and becomes his mistress. During his absence, she falls in love with Drouet’s friend Hurstwood, a middle aged, married, comparatively intelligent culture saloon manager. They finally elope. They live together for three years more. Chicago New York Carrie becomes mature in intellect and emotion, while Hurstwood steadily declines. At last, she thinks him too great a burden and leaves him. Hurstwood sinks lower and lower. After becoming a beggar, he commits suicide, while Carrie becomes a star of musical comedy. In spite of her success, she is lonely and dissatisfied. The theme in Sister Carrie, a novel written by Theodore Dreiser, is materialism. The theme is primarily personified through Carrie with her desire for a fine home, clothes and everything else money can buy. Materialism, including the desire for money, is an important theme in Sister Carrie. The materialism is shown mostly through Carrie's character but also through Hurstwood, a man with a respectable life and money, who still wants more and for that reason commits a crime. The city in itself is also a place of materialism, it is a place that offers all kinds of amusements, pleasures and things to buy, but to participate in what the city has to offer one has to have money. Evaluation He faced every form of attack that a serious artist could encounter misunderstanding, misrepresentation, artistic isolation and commercial seduction. But he survived to lead the rebellion of the 1900s. Dreiser has been a controversial figure in American literary history. His works are powerful in their portrayal of the changing American life, but his style is considered crude. It is in Dreiser’s works that American naturalism is said to have come of age. Dreiser’s novels are formless at times and awkwardly written, and his characterization is found deficient and his prose pedestrian and dull, yet his very energy proves to be more than a compensation. Dreiser’s stories are always solid and intensely interesting with their simple but highly moving characters. Dreiser is good at employing the journalistic method of reiteration to burn a central impression into the reader’s mind. For a commemorative service in 1947, H. L. Mencken wrote a eulogy in which he stuck by the argument that he had been making for over thirtyfive years: despite Dreiser's flaws as a stylist, "the fact remains that he is a great artist, and that no other American of his generation left so wide and handsome a mark upon the national letters. American writing, before and after his time, differed almost as much as biology before and after Darwin. He was a man of large originality, of profound feeling, and of unshakable courage. All of us who write are better off because he lived, worked, and hoped." Here lies the power and permanence that have made Dreiser one of America’s foremost novelists. Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935) Robinson is the first important poet of the twentieth century Poet of transition Pulitzer Prize winner for three times Edwin Arlington Robinson was born on December 22, 1869, in Head Tide, Maine (the same year as W. B. Yeats). His family moved to Gardiner, Maine, in 1870, which renamed "Tilbury Town," became the backdrop for many of Robinson's poems. Robinson described his childhood as stark and unhappy. Born and raised in Maine to a wealthy family, he was the youngest of three sons and not groomed to take over the family business. Instead, he pursued poetry since childhood, joining the local poetry society as its youngest member. He attended Harvard, but his personal life was soon beset by a chain of tragedies that are reflected in his work. His father died, the family went bankrupt, one of his brothers became a morphine addict, and his mother contracted and eventually died from black diphtheria. Robinson spent two years studied at Harvard University as a special student and his first poems were published in the Harvard Advocate. Robinson privately printed and released his first volume of poetry, The Torrent and the Night Before, in 1896 at his own expense. Shortly after, he met a woman, Emma Shepherd, with whom he fell deeply in love, but he was also convinced that marriage and familial responsibilities would hinder his work as a poet, so he introduced her to his eldest brother, who married her. Unable to make a living by writing, he got a job as an inspector for the New York City subway system. In 1902 he published Captain Craig and Other Poems. This work received little attention until President Theodore Roosevelt wrote a magazine article praising it and Robinson. Roosevelt also offered Robinson a sinecure in a U.S. Customs House, a job he held from 1905 to 1910. Robinson dedicated his next work, The Town Down the River (1910), to Roosevelt. Robinson's first major success was The Man Against the Sky (1916). For the last twenty-five years of his life, Robinson spent his summers at the MacDowell Colony of artists and musicians in Peterborough, New Hampshire. Robinson never married and led a notoriously solitary lifestyle. In 1922, Robinson received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his Collected Poems: He won it again in 1925 for The Man Who Died Twice and in 1928 for Tristram, the third part of his trilogy. With his even starting to drink again, claiming that he was doing it to protest Prohibition. He published regularly until the day he died, in New York City in 1935. He died in New York City on April 6, 1935. newfound fame and fortune, he made a radical change in his lifestyle too, tending to himself and Works The Torrent and the Night Before 1896 The Town Down the River 1910 The Man Against the Sky 1916 The Three Taverns 1920 “Richard Cory” “Miniver Cheevy” “Mr. Flood’s Party” Richard Cory As "Richard Cory" is only sixteen lines, we scarce need be reminded at the beginning that because of its compactness each word becomes infinitely important. While stanza one introduces the narrator, more importantly it emphasizes his limited view of Richard Cory. Line one introduces us to Cory while line two establishes that the narrator has only an external view of Cory. From this viewpoint, then, the narrator proceeds to make an assortment of limited value judgments. Richard Cory resembles a king ("crown," "imperially slim," and "richer than a king") ; obviously the speaker imagery (as well as movement in "sole to crown") reveal his concerns with Cory status and wealth (further emphasized by "glittered"). Charles Morris notes the speaker use of Anglicism ("pavement," "sole to crown," "schooled," and "in fine") pictures Cory as "an English king;" thus, the narrator can be seen expressing prejudices in terms of nationalistic pride The poet, with a more profound grasp of life than either, shows us only what life itself would show us; we know Richard Cory only through the effect of his personality upon those who were familiar with him, and we take both the character and the motive for granted as equally inevitable. Therein lies the ironic touch, which is intensified by the simplicity of the poetic form in which this tragedy is given expression. Miniver Cheevy Here we have a man's life-story distilled into sixteen lines. A dramatist would have been under the necessity of justifying the suicide by some train of events in which Richard Cory's character would have inevitably betrayed him. A novelist would have dissected the psychological effects of these events upon Richard Cory. Miniver is the archetypal frustrated romantic idealist, born in the wrong time for idealism. He is close enough to being Robinson himself so that Robinson can smile at him and let the pathos remain unspoken. Miniver Cheevy, child of scorn, Grew lean while he assailed the seasons. He wept that he was ever born, And he had reasons. "Miniver Cheevy" is generally regarded as a self-portrait. The tone, characteristics sketched by Robinson and shared by the poet and Miniver, and the satiric humor of the poem all lead to that interpretation. Yet, although as a satire of the poet himself it is a delightful poem, Robinson jousts with a double-edged satiric lance. More than a clever spoof of Robinson as Miniver, the poem satirizes the age and, especially, its literary taste. In this poem Robinson does not sympathize with Miniver, but lampoons his faults and "laughs at him without reserve in every line.” The poem's combination of feminine endings and short final stanzaic lines contribute to the satiric effect. Furthermore, by making his character ludicrous, Robinson makes clear within the context of the poem that Miniver is out of tune with the age. Mr. Flood's Party "Mr. Flood's Party" is in some ways much like "Miniver Cheevy" and "Richard Cory." It is a character sketch, a miniature drama with hints and suggestions of the past; its tone is a blend of irony, humor, and pathos. Yet it is, if not more sober, at least mote serious, and a finer poem. It is more richly conceived and executed, and it contains two worlds, a world of illusion and a world of reality. The theme is the transience of life; the central symbol is the jug. Both the theme and the symbolic import of the jug are announced in the line "The bird is on the wing, the poet says," though only the theme, implicit in the image, is immediately apparent. The main theme or point of "Mr. Flood's Party" is a consideration of the effects upon human experience of the passage of time. And to the elaboration of this theme virtually all of the major figures of speech or symbols in the poem are functionally and organically related, either directly or indirectly. Evaluation Robinson is a "people poet," writing almost exclusively about individuals or individual relationships rather than on more common themes of the nineteenth century. He exhibits a curious mixture of irony and compassion toward his subjects-most of whom are failures--that allows him to be called a romantic existentialist. He is a true precursor to the modernist movement in poetry. Robinson is famous for his use of the sonnet and the dramatic monologue. Many of his poems are on individuals and individual relationships; most of these individuals are failures. He is traditional in the use of meter; many of his longer works are in blank verse. No poet ever understood loneliness or separateness better than Robinson or knew the self-consuming furnace that the brain can become in isolation, the suicidal hellishness of it, doomed as it is to feed on itself in answerless frustration, fated to this condition by the accident of human birth, which carries with it the hunger for certainty and the intolerable load of personal recollections. The early twentieth century saw American poetry experimenting with new forms and content. He was noted for mastery of conventional forms. He loved the traditional sonnet and quatrain and the often used the old-fashioned language of romantic poetry. But his poetry often focused on the modern problems. Robinson’s poetry includes such typical elements as characterization, indirect and allusive narration, contemporary setting, psychological realism and interest in exploring the tangles of human feelings and relationships, and expressing the modern fears and uncertainty in his own era. Carl Sandburg (1878-1967) American poet, historian, novelist and folklorist,folk musician,Political Organizer, Reporter the singing bard a central figure in the “Chicago Renaissance” Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, as the son of poor Swedish immigrant parents. His father was August Sandburg, a blacksmith and railroad worker, who had changed his name from Johnson. His mother was the former Clara Anderson. Carl Sandburg worked from the time he was a young boy. He quit school following his graduation from eighth grade in 1891 and spent a decade working a variety of jobs. He delivered milk, harvested ice, laid bricks, threshed wheat in Kansas, and shined shoes in Galesburg's Union Hotel before traveling as a hobo in 1897. His experiences working and traveling greatly influenced his writing and political views. He saw first-hand the sharp contrast between rich and poor, a dichotomy that instilled in him a distrust of capitalism. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898 Sandburg volunteered for service, and at the age of twenty was ordered to Puerto Rico, where he spent days battling only heat and mosquitoes. Upon his return to his hometown later that year, he entered Lombard College, supporting himself as a call fireman. Sandburg's college years shaped his literary talents and political views. While at Lombard, Sandburg joined the Poor Writers' Club, an informal literary organization whose members met to read and criticize poetry. Poor Writers' founder, Lombard professor Phillip Green Wright, a talented scholar and political liberal, encouraged the talented young Sandburg. The Sandburgs soon moved to Chicago, where Carl became an editorial writer for the Chicago Daily News. Sandburg honed his writing skills and adopted the socialist views of his mentor before leaving school in his senior year. Sandburg sold stereoscope views and wrote poetry for two years before his first book of verse, In Reckless Ecstasy, was printed on Wright's basement press in 1904. As the first decade of the century wore on, Sandburg grew increasingly concerned with the plight of the American worker. In 1907 he worked as an organizer for the Wisconsin Social Democratic party, writing and distributing political pamphlets and literature. At party headquarters in Milwaukee, Sandburg met Lilian Steichen, whom he married in 1908. Sandburg was virtually unknown to the literary world when, in 1914, a group of his poems appeared in the nationally circulated Poetry magazine. Two years later his book Chicago Poems was published, and the thirty-eight-year-old author found himself on the brink of a career that would bring him international acclaim. In the twenties, he started some of his most ambitious projects, including his study of Abraham Lincoln. His Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, published in 1926, was Sandburg's first financial success. The War Years, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1940. Sandburg's Complete Poems won him a second Pulitzer Prize in 1951. From 1945 he lived as a farmer and writer, breeding goats and folk-singing, in Flat Rock, North Carolina. Sandburg died at his North Carolina home July 22, 1967. His ashes were returned, as he had requested, to his Galesburg birthplace. In the small Carl Sandburg Park behind the house, his ashes were placed beneath Remembrance Rock, a red granite boulder. Works Collections Chicago poems Cornhuskers Smoke and Steel Good Morning, America The People, Yes 1916 1918 1920 1928 1936 Poems “Chicago” “The Harbour” “Fog” “I Am the People, the Mob” Collections of folk songs The American Songbag Biographies Abraham Lincoln: The War Years The Prairie Years 1927 1939 1926 Evaluation Carl Sandburg was one of the best know and most widely read poets in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s. His subject matter is the people themselves. Like Walt Whitman, Sandburg exclaimed: “I am the People, the Mob!” His poetic tone is always affirmative and he is free from rhyme and regular meter. In Whitmanesque free verse he sings about factories and the building of skyscrapers. Sandburg’s form is the free verse with its lines of irregular length, its looser speech rhythms, and the absence of end rhyme. Sandburg won Pulitzer prizes in history and poetry. He was always trying new forms of writing and taking on new challenges. Once he wrote, "I had studied monotony. I decided whatever I died of, it would not be monotony." Sandburg's poems are often full of slang and the language of ordinary Americans. Sandburg wrote poems about Chicago-the "stormy, husky, brawling" life of the city and the lonely peace of the prairie. He wrote about real people with real problems and he wrote by his own rules. To many, Sandburg was a latter-day Walt Whitman, writing expansive, evocative urban and patriotic poems and simple, childlike rhymes and ballads. At heart he was totally unassuming, notwithstanding his national fame. What he wanted from life, he once said, was "to be out of jail...to eat regular...to get what I write printed,...a little love at home and a little nice affection hither and yon over the American landscape,...(and) to sing every day." He played a significant role in the development in poetry that took place during the first two decades of the 20th century. In the first quarter of the 20th century, Sandburg was a breaker of conventions and an innovator of American poetry. Appreciation Carl Sandburg's poem, "Fog," is among the few exceptions that mark Sandburg's break from free verse poetry. Fog", a mere six lines long, is written in verse-form and is an innocent expression of finding beauty in an ordinary world. "Fog" is a delightful poem, using simple imagery. There aren't a lot of words, and the image, at first look, isn't very complex. However, like a haiku poem, there is far more than just the description of the movement of misty air. Fog leaves the natural and becomes surreal and ethereal, but always anchored to the familiar reality we all know. Fog The fog comes on little cat feet. It sits looking over harbor and city on silent haunches and then moves on The Harbor The contrast of the city to the shore is exquisite. One underlying meaning one may extricate from the poem is that of one who has had his share of lovers, all of which left him unsatisfied. Yet the shore, and its image of gleaming beauty and youth gives the idea of a new love, one with meaning. The blue lake appears to serve as a symbol for hope and rebirth in the sexual awareness of the poet. Chicago The overwhelming theme in Illinois is the city of Chicago. This poem was part of the book of Chicago Poems by Sandburg published in 1916. Sandburg said that the difference between Dante, Milton, and himself was that they wrote about hell and never saw the place whereas he had written about Chicago. Chicago I Am the People, the Mob Sandburg the poet gave a powerful voice to the "people--the mob--the crowd--the mass“. He championed the cause of "the Poor, millions of the Poor, patient and toiling; more patient than crags, tides, and stars; innumerable, patient as the darkness of night" . He was established as the poet of the American people, pleading their cause; reciting their songs, stories, and proverbs; celebrating their spirit and their vernacular; and commemorating the watershed experiences of their shared national life. Chicago In 1930, he became the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. During his lifetime he published 22 novels. Who was he? Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) Life Experiences Born in the town of Sank Center, Minnesota; Graduated from Yale; Became an editor and a writer; Published Main Street in 1920 and won the Nobel Prize in literature; Published Babbitt in 1922. Main Works Our Mr. Wrenn (1914) The Trial of the Hawk (1915) Main Street (1920) Babbitt (1922) Arrowsmith (1925) The Man Who Knew Coolidge (1928) It Can’t Happen Here (1935) Main Street Main Street was a study of idealism and reality in a narrow-minded small-town. "Main Street is the continuation of main Streets everywhere." It meant cheap shops, ugly public buildings, and citizens who were bound by rigid conventions. The book had parallels with the author's own early life. The protagonist also has skin problems. Lewis claimed that Main Street was read "with the same masochistic pleasure that one has in sucking an aching tooth." The photographs of “Main Street” Illustrations of the photographs When Sinclair Lewis wrote “Main Street”, it was generally believed that his home town, Sauk Center, Minnesota, was the locale although he called his fictional town Gopher Prairie. Though the heroine of “Main Street” Lewis expressed his own feelings, particularly his dissatisfactions. Sinclair Lewis’ Nobel Prize Address (After praising Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe and other contemporary American writers:) I solute them, with a joy in being not yet too far removed from the determination to give to the America that has mountains and endless prairies, enormous cities and lost farm cabins, billions of money and tons of faith, to an America that is as strange as Russia and as complex as china, a literature worthy of her vastness. Main Street (1920) Lewis criticized at times the American way of living, but his basic view was optimistic. "His central characters are the pioneer, the doctor, the scientist, the businessman, and the feminist. The appeal of his best fiction lies in the opposition between his idealistic protagonists and an array of fools, charlatans, and scoundrels - evangelists, editorialists, pseudo-artists, cultists, and boosters." Babbitt (1922) The novel behind the name, Babbitt is Sinclair Lewis’s classic commentary on middle-class society. George Follanbee Babbitt has acquired everything required to fit neatly into the mold of social expectation—except total comfort with it. Distracted by the feeling that there must be more, Babbitt starts pushing limits, with many surprising results. Babbitt (1922) He appears to be a stereotype of millions of American men. He sells real estate and lives in a typical middle-class house. He has a typical family, a wife and three children. He expresses typical American prejudices. Babbitt (1922) He has yearnings, fantasies of youth and love and escape. The slow rise and all too rapid failure of his efforts to be himself instead of falling into the typical mold is shown. He is grumpily dissatisfied with the existence he leads. He tries a mild sexual adventure. He consorts briefly with radical thinkers. He expresses unorthodox ideas. Sinclair Lewis A sensational event was changing from the brown suit to the gray the contents of his pockets. He was earnest about these objects. They were of eternal importance, like baseball or the Republican Party. Chapter V Henry L. Mencken (1880-1956) Mencken’s Life Experiences Born in Baltimore; Studied at the Baltimore Polytechnic; Began his career on the Baltimore Morning Herald at the age of 18; from 1906 until his death was on the staff of the Baltimore Sun or Evening Sun; (1914-1923) was coeditor of the Smart Set with George Jean Nathan; together they founded the American Mercury in 1924, and Mencken was its sole editor from 1925 to 1933. Mencken’s Major Works The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States, 2nd ed. (1921) Prejudices, First Series “Criticism of Criticism of Criticism” “A Neglected Anniversary” The American Language (1919) It contrasted American English with British English; It explained the origin of many colorful American slang expressions; It examined uniquely American geographical and personal names; It traced the influence of immigrant languages on the American idiom. Mencken’s Attack His attack was devastatingly direct, with invective as a substitute for caricature and with no trace of obliqueness or subtlety. He derided the smugness of the middle-class businessman, the narrowness of American cultural life, and the harshness of American Puritanism. The American Mercury It was the most influential magazine of its time. In the magazine, he wanted to “stir up the animals.” He wanted to arouse his antagonists, and he usually succeeded. Nothing was sacred to him. He attacked the churches, the business and the government in America. Comment on Mencken & His Writing Mencken was the most prominent newspaperman, book reviewer, and political commentator of his day. Mencken's writing is endearing because of its wit, its crisp style, and the obvious delight he takes in it. He had a rollicking, rambunctious style of writing. He meant what he said, but he said it with wit. Mencken’s Witty Remarks (1) Every third American devotes himself to improving and uplifting his fellow-citizens, usually by force. --from his Prejudices: First Series Badchelors know more about women than married men. If they didn’t they’d be married, too. --from his Chrestomathy 621 Mencken’s Witty Remarks (2) A celebrity is one who is known to many persons he is glad he doesn't know. --from his Chrestomathy 617 Conscience—the accumulated sediment of ancestral faint-heartedness. --quoted in Smart Set Dec. 1921 The most costly of all follies is to believe passionately in the palpably not true. It is the chief occupation of mankind. --from his Chrestomathy 616 Mencken and His Rival Henry L. Mencken William Jennings Bryan The “monkey trial” at Dayton, Tenn. Mencken's Assessment of Life in U.S. We live in a land of abounding quackeries, and if we do not learn how to laugh we succumb to the melancholy disease which afflicts the race of viewers-with-alarm... In no other country known to me is life as safe and agreeable, taking one day with another, as it is in These States. Mencken's Assessment of Life in the U.S (continued) Even in a great Depression few if any starve, and even in a great war the number who suffer by it is vastly surpassed by the number who fatten on it and enjoy it. Thus my view of my country is predominantly tolerant and amiable. I do not believe in democracy, but I am perfectly willing to admit that it provides the only really amusing form of government ever endured by mankind. Chapter VI F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) F. Scott Fitzgerald Dominant influences on FSF Aspiration; Literature; Princeton; Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald; Alcohol. Life Experiences (1) 24 September 1896 Birth of Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald in St. Paul, Minnesota. October 1909 Publication of “The Mystery of the Raymond Mortgage”, FSF’s first appearance in print. September 1913 FSF enters Princeton University with Class of 1917 February 1919 FSF discharged from army. Planning to marry Zelda Sayre. Life Experiences (2) 26 March 1920 Publication of This Side of Paradise. 3 April 1920 Marriage of FSF and Zelda Sayre. 10 April 1925 Publication of The Great Gatsby. 21 December 1940 FSF dies of heart attack. Major Works This Side of Paradise (1920) Flappers and Philosophers (1920) The Beautiful and Damned (1920) Tales of the Jazz Age (1922) The Great Gatsby (1925) Tender Is the Night (1934) The Last Tycoon (1941) This Side of Paradise (1920) This Side of Paradise: an introduction F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote the first draft of his first novel in the army during 1917 and 1918. The working titles were "The Romantic Egoist" and "The Romantic Egotist." It was rejected by Charles Scribner's Sons in 1918. In 1919 Fitzgerald rewrote the book as This Side of Paradise. Its publication by Scribners in April 1920 made him a literary celebrity before his twenty-fourth birthday. Set mostly at Princeton, This Side of Paradise was the most influential American college novel of its time and announced the arrival of a younger generation with new values and aspirations. The Great Gatsby (1925) The Great Gatsby: plot Jay Gatsby is a man possessed—driven by greed, ambition and, most of all, an unwavering desire for a woman he met before the Great War, when he was poor and she was unobtainable. As Gatsby reinvents himself in an attempt to buy his way into the social elite of Long Island's Gold Coast, he yearns to rekindle his romance with the woman who stole his heart years before. But when the chance finally arrives, a shadow of tragedy is cast over what Gatsby long-imagined would be his triumphant moment. The Great Gatsby: Important Quotations Explained (1) 1. I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool. 2. He had one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced, or seemed to face, the whole external world for an instant and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just as far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself. The Great Gatsby: Important Quotations Explained (2) 3. The truth was that Jay Gatsby, of West Egg, Long Island, sprang from his Platonic conception of himself. He was a son of God—a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that—and he must be about His Father’s business, the service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty. So he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a seventeen year old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end. The Great Gatsby: Important Quotations Explained (3) 4. That’s my Middle West . . . the street lamps and sleigh bells in the frosty dark. . . . I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all—Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life. 5. Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther … And then one fine morning— So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past. Study Questions o Discuss Gatsby’s character as Nick perceives him throughout the novel. What makes Gatsby “great”? o What is Nick like as a narrator? Is he a reliable storyteller, or does his version of events seem suspect? How do his qualities as a character affect his narration? o What are some of The Great Gatsby’s most important symbols? What does the novel have to say about the role of symbols in life? o How does the geography of the novel dictate its themes and characters? What role does setting play in The Great Gatsby? F. Scott Fitzgerald Fitzgerald’s clear, lyrical, colorful, witty style evoked the emotions associated with time and place. The chief theme of Fitzgerald’s work is aspirationòthe idealism he regarded as defining American character. Another major theme was mutability or loss. As a social historian Fitzgerald became identified with the Jazz Age: “It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess, and it was an age of satire,” he wrote in Echoes of the Jazz Age. Chapter VII John Steinbeck (1902-1968) John Steinbeck John Steinbeck received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962. Life Experiences Born: February 27,1902; 132 Central Avenue, Salinas, CA (what is now the reception room of the Steinbeck House) Graduated from Salinas High School--June 1919 Attended Stanford University--1919-1925 Died in New York, December 20,1968 Steinbeck Family Father: John Ernst Steinbeck (1863-1935), County Treasurer Mother: Olive Hamilton Steinbeck (1867-1934), Teacher Wives: Carol Henning Steinbeck Brown, married 1930 and divorced 1942; Gwyndolyn Conger Steinbeck, married 1943 and divorced 1948; Elaine Anderson Scott Steinbeck, married 1950 Sons: Thomas Steinbeck, August 2,1944; John Steinbeck IV, June 12, 1946 - February 7,1991 Major Works Cup of Gold, 1929 The Pastures of Heaven, 1932 Tortilla Flat, 1935 In Dubious Battle, 1936 Of Mice and Men, 1937 The Red Pony, 1937 The Grapes of Wrath, 1939 Cannery Row, 1945 The Pearl, 1947 East of Eden, 1952 Travels with Charley, 1962 Quotations “Man, unlike any other thing organic or inorganic in the universe, grows beyond his work, walks up in the stairs of his concepts, emerges ahead of his accomplishments.” (from The Grapes of Wrath) The Grapes of Wrath (1939) Cover of 1st Edition Movie Poster The Grapes of Wrath Above: "66 is the mother road, the road of flight." Right 1: the setting for Chapters 18-30 of The Grapes of Wrath Right 2: places mentioned in Chapter 12 of The Grapes of Wrath The Grapes of Wrath The Grapes of Wrath- the title originated from Julia Ward Howe's The Battle Hymn of the Republic (1861)--Steinbeck traveled around California migrant camps in 1936. The Exodus story of Okies on their way to an uncertain future in California, ends with a scene in which Rose of Sharon, who has just delivered a stillborn child, suckles a starving man with her breast. The Ending of The Grapes of Wrath Rose of Sharon loosened one side of the blanket and bared her breast. 'You got to,' she said. She squirmed closer and pulled his head close. 'There!' she said. 'There.' Her hand moved behind his head and supported it. Her fingers moved gently in his hair. She looked up and across the barn, and her lips came together and smiled mysteriously. The Ending of The Grapes of Wrath Rose of Sharon loosened one side of the blanket and bared her breast. 'You got to,' she said. She squirmed closer and pulled his head close. 'There!' she said. 'There.' Her hand moved behind his head and supported it. Her fingers moved gently in his hair. She looked up and across the barn, and her lips came together and smiled mysteriously. Themes of The Grapes of Wrath Man’s Inhumanity to Man; The Saving Power of Family and Fellowship; The Dignity of Wrath; The Multiplying Effects of Selfishness and Altruism. Questions 1. 2. 3. Half of the chapters in The Grapes of Wrath focus on the dramatic westward journey of the Joad family, while the others possess a broader scope, providing a more general picture of the migration of thousands of Dust Bowl farmers. Discuss this structure. Why might Steinbeck have chosen it? How do the two kinds of chapters reinforce each other? What is Jim Casy’s role in the novel? How does his moral philosophy govern the novel as a whole? Many critics have noted the sense of gritty, unflinching realism pervading The Grapes of Wrath. How does Steinbeck achieve this effect? Do his character portrayals contribute, or his description of setting, or both?