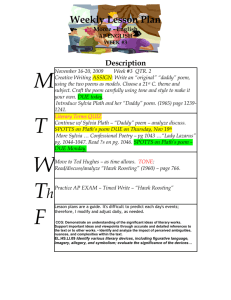

Dummies Guide to

Sylvia Plath

DUMMIES GUIDE TO:

WHO WAS SHE?

Sylvia Plath was born to Aurelia Schober Plath and Otto Emile Plath on October 27, 1932 in

Jamaica Plain Massachusetts. She published her first poem at the age of eight in a children’s magazine. She was born into a relatively poor family during the depression. This resulted in her rarely seeing her father as a child. Otto Plath died when she was eight. This resulted in her losing faith in Christianity for the rest of her life.

Growing up, Sylvia Plath would always strive to be the best daughter she could be. She was a straight A student and received constant praise from teachers and peers for her natural gift with a pen. She enrolled to college when she was 18 and received even more praise there, excluding the decline from Harvard to attend a summer course. Her mother would soon discover the scars on Plath’s legs as she, “...wanted to see if I had the guts.” She was then admitted to a psychiatrist for electroshock and insulin shock therapy. These incidents left her depressed and when she returned the summer home she attempted suicide on August 24, 1953.

She married the English poet Ted Hughes in 1960 and had two children with him. As they were both poets, they spent much of their time writing poems and short stories and looking to publish them. Their relationship was said to be an abusive one and the reason for their separation was

Hughes cheating on his spouse. After this, she went on a poetic rampage (most of which were published in Ariel).

She then committed suicide on February 11, 1963. Her autobiographic, fiction novel Bell Jar was published after her death.

What was it? And how did it reflect her and how can you see it?

HER POETRY

WHAT WAS SHE KNOWN FOR?

She is though to be a leader in the realm of confessional poetry:

Private experiences with and feelings about death, trauma, depression and relationships were addressed in this type of poetry, often in an autobiographical manner.

REPEATING THEMES (AND HOW THEY RELATE TO

HER LIFE)

Father figures – depicted as comforting, abusive, and sexual.

After losing her father so early in her life, her depiction of him became an obsession and she constantly saw him in different lights as the ‘father’ he might have been.

The small amount of time she was with her father, he was known to have been neglectful.

Her obsession with him could have been interpreted to her as a sexual one, as she was urged to bond with him in the typical father daughter ways, both emotionally and mentally, both of these were projected to a physical need.

Bees, Stinging, and Bee keeping – depicted in emotions of fear, jealousy, and longing.

- As her father had taken up the hobby of bee keeping, she showed these three emotions in her poetry.

-As seen in The Bee Meeting and Stings , she demonstrates a feeling of love onto the poor creatures and a feeling of fear onto herself for her protection (this possibly stemming from her fear/fascination with death from her father’s).

Physical Abuse – Self mutilation and a fascination with such.

- From her intimate relationships with death (both from her father’s death and her own almost drowning at the age of 10) stemmed a fascination with physical pain and the separation from life and death.

- The scars of self mutilation on her legs as a young woman and her attempted suicide in 1953 are evidence of her love of physical pain. In Cut , her descriptive similes and metaphors to the skin and the blood give further evidence to this theory.

Do you understand her messages in her work and how they’re confessional?

POEMS (WITH AUDIO) AND ANALYSIS

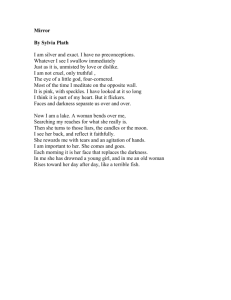

DADDY

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time--

Marble-heavy, a bag full of God,

Ghastly statue with one gray toe

Big as a Frisco seal

And a head in the freakish Atlantic

Where it pours bean green over blue

In the waters off beautiful Nauset.

I used to pray to recover you.

Ach, du.

In the German tongue, in the Polish town

Scraped flat by the roller

Of wars, wars, wars.

But the name of the town is common.

My Polack friend

Says there are a dozen or two.

So I never could tell where you

Put your foot, your root,

I never could talk to you.

The tongue stuck in my jaw.

It stuck in a barb wire snare.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

I thought every German was you.

And the language obscene

An engine, an engine

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.

The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of

Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gipsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You--

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

You stand at the blackboard, daddy,

In the picture I have of you,

A cleft in your chin instead of your foot

But no less a devil for that, no not

Any less the black man who

Bit my pretty red heart in two.

I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

I thought even the bones would do.

But they pulled me out of the sack,

And they stuck me together with glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I'm finally through.

The black telephone's off at the root,

The voices just can't worm through.

If I've killed one man, I've killed two--

The vampire who said he was you

And drank my blood for a year,

Seven years, if you want to know.

Daddy, you can lie back now.

There's a stake in your fat black heart

And the villagers never liked you.

They are dancing and stamping on you.

They always knew it was you.

Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I'm through.

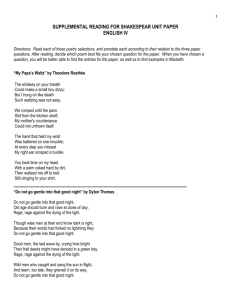

ANALYSIS OF DADDY

BY: ELIZABETH BOULET

“Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time--

Marble-heavy, a bag full of God

…

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

…

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You--

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

…

A cleft in your chin instead of your foot

But no less a devil for that, no not

Any less the black man who

Bit my pretty red heart in two.”

References to various religions

-She is denouncing her faith through her father.

-She explores various ones that may have relation to her through her roots (as she was of Polish descent).

“Ach, du.

…

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

I thought every German was you.

…

An engine, an engine

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.

…

The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

…

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

…

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

…

The vampire who said he was you

And drank my blood for a year,

Seven years, if you want to know.

…

There's a stake in your fat black heart”

• Her father is compared to the devil and the devil is compared to Hitler and then again to a vampire.

-References to the military power of the Nazis in WWII and the

Holocaust, both of these show her fear of her father, whether it would be from his presence as a father or because of the relationship they shared.

-She compares him to a vampire for “biting her pretty little heart” and then mentions how she projected her relationship with her father to one with other men (Ted

Hughes her husband).

“I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

…

Seven years, if you want to know.”

Poem is obviously an autobiography with the various mentions of life moments

- Her attempted suicide at the age of 20

- Her marriage of 6-7 years

- Her father’s death when she was 8 (ten here)

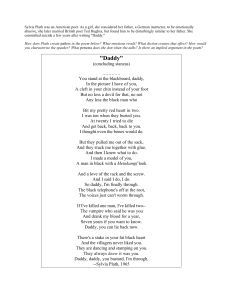

CUT

(Audio begins at 9:57)

What a thrill ----

My thumb instead of an onion.

The top quite gone

Except for a sort of hinge

Of skin,

A flap like a hat,

Dead white.

Then that red plush.

Little pilgrim,

The Indian's axed your scalp.

Your turkey wattle

Carpet rolls

Straight from the heart.

I step on it,

Clutching my bottle

Of pink fizz. A celebration, this is.

Out of a gap

A million soldiers run,

Redcoats, every one.

Whose side are they one?

O my

Homunculus, I am ill.

I have taken a pill to kill

The thin

Papery feeling.

Saboteur,

Kamikaze man ----

The stain on your

Gauze Ku Klux Klan

Babushka

Darkens and tarnishes and when

The balled

Pulp of your heart

Confronts its small

Mill of silence

How you jump ----

Trepanned veteran,

Dirty girl,

Thumb stump.

CUT ANALYSIS

BY: ELIZABETH BOULET

• Mention of the cut being a ‘thrill’ leads the reader to believe she did it deliberately.

-For enjoyment of pain or the mere fascination?

“Little pilgrim,

The Indian's axed your scalp.

Your turkey wattle

Carpet rolls

Straight from the heart”

• The wars between pilgrims and

Indians were caused by past deceptions that stemmed hate.

-Comparison to her relationship with her father?

“Carpet rolls

Straight from the heart.

I step on it,

Clutching my bottle

Of pink fizz. A celebration, this is.”

Could she mean a red carpet, similar to the one from Hollywood?

Pink fizz and celebration could be a comparison of pain killers/peroxide to champagne

The homunculus mentioned may be a representation of her conscious.

The feeling of celebration shifts quickly to one of war and hate.

The mention of the Kamikaze and the KKK, both of which are

‘unclean’ (with the words

‘Saboteur’ and the ‘tarnished

Babushka’)

Trepanning (the act of drilling a hole into the skull) the veteran implies he is either used completely (he serves no farther use) or (from certain accounts) is relieved of a pounding pressure.

- As for the ‘dirty girl’ line, as it sounds like she is using the two lines interchangeably, this could also be applied as a ‘pressure’ is alleviated or she has lost her use. Both in terms of her innocence and virginity.

LADY LAZARUS

(Audio begins at 6:44)

I have done it again.

One year in every ten

I manage it-----

A sort of walking miracle, my skin

Bright as a Nazi lampshade,

My right foot

A paperweight,

My featureless, fine

Jew linen.

Peel off the napkin

O my enemy.

Do I terrify?-------

The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth?

The sour breath

Will vanish in a day.

Soon, soon the flesh

The grave cave ate will be

At home on me

And I a smiling woman.

I am only thirty.

And like the cat I have nine times to die.

This is Number Three.

What a trash

To annihilate each decade.

What a million filaments.

The Peanut-crunching crowd

Shoves in to see

Them unwrap me hand and foot ------

The big strip tease.

Gentleman , ladies

These are my hands

My knees.

I may be skin and bone,

Nevertheless, I am the same, identical woman.

The first time it happened I was ten.

It was an accident.

The second time I meant

To last it out and not come back at all.

I rocked shut

As a seashell.

They had to call and call

And pick the worms off me like sticky pearls.

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

I do it so it feels like hell.

I do it so it feels real.

I guess you could say I've a call.

It's easy enough to do it in a cell.

It's easy enough to do it and stay put.

It's the theatrical

Comeback in broad day

To the same place, the same face, the same brute

Amused shout:

'A miracle!'

That knocks me out.

There is a charge

For the eyeing my scars, there is a charge

For the hearing of my heart---

It really goes.

And there is a charge, a very large charge

For a word or a touch

Or a bit of blood

Or a piece of my hair on my clothes.

So, so, Herr Doktor.

So, Herr Enemy.

I am your opus,

I am your valuable,

The pure gold baby

That melts to a shriek.

I turn and burn.

Do not think I underestimate your great concern.

Ash, ash---

You poke and stir.

Flesh, bone, there is nothing there----

A cake of soap,

A wedding ring,

A gold filling.

Herr God, Herr Lucifer

Beware

Beware.

Out of the ash

I rise with my red hair

And I eat men like air.

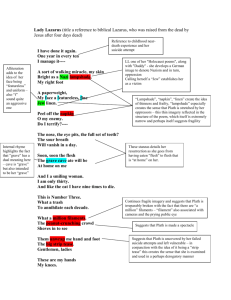

LADY LAZARUS ANALYSIS

BY: MIA MENARD

This poem is really about Sylvia's suicides attempts and near death experiences. Her reference to Nazis and Jews are actually a metaphor also used in “Daddy”, and is really painting a picture for the reader. Like the Jews in the Holocaust, she is a victim, while the doctors and others figures are her oppressors like the Nazis.

The poem begins after she has been saved from death for the third time. Although she is a terrifying corpse she will soon become the woman she was again, she will return to normality.

Concerned people have become spectators watching a show, not caring for her, only wanting excitement.

She refers to a near-death accident from when she was ten, and then refers to a suicide attempt in her twenties. Her attempts have now become a show, an act she performs very well. Yet she is still amazed by people's awe each time she is "saved", still amazed that they could be so entertained and excited when they eye her scars and realise what she did. She is their

"valuable", their "opus", which they display.

She knows how worried they are but she burns like a phoenix, and although she is ash, leaving little to remember her by, she warns both God and the Devil, which could merely represent faith, she refers to them as "Herr", oppressors, her enemy, she warns them that she will rise again and will "eat men like air" she will go on living, wreaking havoc just as before, because although she may try to die, although she may get close "like a cat" she has "nine times to die."

STING

Bare-handed, I hand the combs.

The man in white smiles, bare-handed,

Our cheesecloth gauntlets neat and sweet,

The throats of our wrists brave lilies.

He and I

Have a thousand clean cells between us,

Eight combs of yellow cups,

And the hive itself a teacup,

White with pink flowers on it,

With excessive love I enameled it

Thinking 'Sweetness, sweetness.'

Brood cells gray as the fossils of shells

Terrify me, they seem so old.

What am I buying, wormy mahogany?

Is there any queen at all in it?

If there is, she is old,

Her wings torn shawls, her long body

Rubbed of its plush ----

Poor and bare and unqueenly and even shameful.

I stand in a column

Of winged, unmiraculous women,

Honey-drudgers.

I am no drudge

Though for years I have eaten dust

And dried plates with my dense hair.

And seen my strangeness evaporate,

Blue dew from dangerous skin.

Will they hate me,

These women who only scurry,

Whose news is the open cherry, the open clover?

It is almost over.

I am in control.

Here is my honey-machine,

It will work without thinking,

Opening, in spring, like an industrious virgin

To scour the creaming crests

As the moon, for its ivory powders, scours the sea.

A third person is watching.

He has nothing to do with the bee-seller or with me.

Now he is gone

In eight great bounds, a great scapegoat.

Here is his slipper, here is another,

And here the square of white linen

He wore instead of a hat.

He was sweet,

The sweat of his efforts a rain

Tugging the world to fruit.

The bees found him out,

Molding onto his lips like lies,

Complicating his features.

They thought death was worth it, but I

Have a self to recover, a queen.

Is she dead, is she sleeping?

Where has she been,

With her lion-red body, her wings of glass?

Now she is flying

More terrible than she ever was, red

Scar in the sky, red comet

Over the engine that killed her ----

The mausoleum, the wax house.

STING ANALYSIS

BY: MIA MENARD

In the last two paragraphs of stings, imagery, allusion and antithesis are employed by Sylvia to develop her attitude towards men. In this section of “stings” she uses the “queen bee” as a symbol of herself.

Which is a fiery, angry, vengeful daughter who rises up in spite of the man – her husband, ted – described in lines 38-50 (he has nothing....complicating his features_. Since most of plath’s work is confessional poetry it can be analyzed not only by her use of poetic devices but by her personal history as well she sensed an attraction between her husband and Assia Wevil which may have provided the motivation for much of “Stings.” Lines in this section of the poem especially 51/52(they thought death was worth it but I/Have a self to recover a queen) indicate her desire to assert her independence not only from Ted but from all the other female bees, who die when they sting – “Sting” in this case could mean sacrificing themselves for me, from this standpoint “stings” can be seen as a feminist work as call as an “anti-ted” poem.