Death of a Salesman

advertisement

A QUOTATION

Remembering the Late Philip Seymour Hoffman July 23 1967 - February 2 2014

REVIEWS and a BIOGRAPHY

Some notes for understanding this play--including flashback

btyb Mrs. Hanzel

"Every man," said Mr. Miller, "has an image of himself which fails in

one way or another to correspond with reality. It's the size of the

discrepancy between illusion and reality that matters. The closer a

man gets to knowing himself, the less likely he is to trip up on his own

illusions."

Remembering the late Philip Seymour Hoffman's Willy Loman Broadway will dim its lights

Wednesday evening in memory of the Oscar-winning actor, who earned the most recent of his

three Tony nominations for Mike Nichols' 2012 revival of "Death of a Salesman."

NEW YORK -- It's rare to hear grown men choke back sobs during a play, but that's what the

emotional nakedness of Philip Seymour Hoffman's Willy Loman, a man broken by his own

hollow faith in the American Dream, elicited from the audience for the 2012 Broadway

production of Death of a Salesman.

Accepting the Tony Award for best revival of a play that year, director Mike Nichols talked

about the blood spilled on the stage every night by the remarkable ensemble of actors playing

the Loman family, which included Hoffman, Andrew Garfield, Linda Emond and Finn

Wittrock (all pictured above).

Watching the production, a wrenching sense emerged of people who had been through the

rigors of life together, in much the same way America had been battered by the Great

Recession. A number of Broadway productions have tapped into the collective hurt inflicted on

the country by the 21st century economic crisis. But arguably none has had the visceral gut

impact of this trenchant staging of Arthur Miller's 1949 masterwork.

Hoffman's death has justly sparked a wave of grief for a versatile screen talent whose career

has been cut tragically short. But his ties to the theater are no less indelible and will be felt most

acutely in the New York stage community.

When Hoffman shambled onto the Ethel Barrymore Theatre stage dragging Willy's sample

cases, he was 44, almost two decades younger than the character as written. But he had the

stature and gravitas of an actor 20 years his senior. His Willy Loman was deluded yet fearful,

blinkered yet ruminative, belligerently proud yet humiliatingly lost. It was a lacerating

performance without an ounce of vanity, which exposed the unforgiving cruelty of a society that

measures a man's value by his professional standing.

Hoffman's Broadway appearances were relatively few, but he chose discerningly, receiving a

Tony nomination for each of the three productions in which he starred.

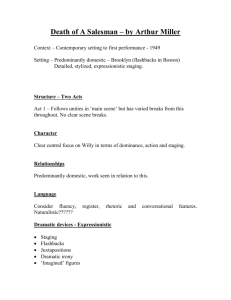

Death of a Salesman

February 11, 1949

At the Theatre

By BROOKS ATKINSON

rthur Miller has written a superb drama. From every point of

view "Death of a Salesman," which was acted at the Morosco

last evening, is rich and memorable drama. It is so simple in style and

so inevitable in theme that is scarcely seems like a thing that has

been written and acted. For Mr. Miller has looked with compassion

into the hearts of some ordinary Americans and quietly transferred their hope and anguish to the

theatre. Under Elia Kazan's masterly direction, Lee J. Cobb gives a heroic performance, and every

member of the cast plays like a person inspired.

Two seasons ago Mr. Miller's "All My Sons" looked like the work of an honest and able

playwright. In comparison with the new drama, that seems like a contrived play now. For

"Death of a Salesman" has the flow and spontaneity of a suburban epic that may not be

intended as poetry but becomes poetry in spite of itself because Mr. Miller has drawn it out of

so many intangible sources.

It is the story of an aging salesman who has reached the end of his usefulness on the road.

There has always been something unsubstantial about his work. But suddenly the unsubstantial

aspects of it overwhelm him completely. When he was young, he looked dashing; he enjoyed

the comradeship of other people--the humor, the kidding, the business.

In his early sixties he knows his business as well as he ever did. But the unsubstantial things

have become decisive; the spring has gone from his step, the smile from his face and the

heartiness from his personality. He is through. The phantom of his life has caught up with him.

As literally as Mr. Miller can say it, dust returns to dust. Suddenly there is nothing.

This is only a little of what Mr. Miller is saying. For he conveys this elusive tragedy in terms of

simple things--the loyalty and understanding of his wife, the careless selfishness of his two

sons, the sympathetic devotion of a neighbor, the coldness of his former boss' son--the bills,

the car, the tinkering around the house. And most of all: the illusions by which he has lived-opportunities missed, wrong formulas for success, fatal misconceptions about his place in the

scheme of things.

Writing like a man who understands people, Mr. Miller has no moral precepts to offer and no

solutions of the salesman's problems. He is full of pity, but he brings no piety to it. Chronicler of

one frowsy corner of the American scene, he evokes a wraith-like tragedy out of it that spins

through the many scenes of his play and gradually envelops the audience.

As theatre "Death of a Salesman" is no less original than it is as literature. Jo Mielziner, always

equal to an occasion, has designed a skeletonized set that captures the mood of the play and

serves the actors brilliantly. Although Mr. Miller's text may be diffuse in form, Mr. Kazan has

pulled it together into a deeply moving performance.

Mr. Cobb's tragic portrait of the defeated salesman is acting of the first rank. Although it is

familiar and folksy in the details, it has something of the grand manner in the big size and the

deep tone. Mildred Dunnock gives the performance of her career as the wife and mother--plain

of speech but indomitable in spirit. The parts of the thoughtless sons are extremely well played

by Arthur Kennedy and Cameron Mitchell, who are all young, brag and bewilderment.

Other parts are well played by Howard Smith, Thomas Chalmers, Don Keefer, Alan Hewitt and

Tom Pedi. If there were time, this report would gratefully include all the actors and fabricators

of illusion. For they all realize that for once in their lives they are participating in a rare event in

the theatre. Mr. Miller's elegy in a Brooklyn sidestreet is superb.

The Crucible January 23, 1953

By BROOKS ATKINSON

rthur Miller has written another powerful play. "The Crucible," it is called, and it opened at the Martin

Beck last evening in an equally powerful performance. Riffling back the pages of American history, he

has written the drama of the witch trials and hangings in Salem in 1692. Neither Mr. Miller nor his

audiences are unaware of certain similarities between the perversions of justice then and today.

But Mr. Miller is not pleading a case in dramatic form. For "The Crucible," despite its current

implications, is a self-contained play about a terrible period in American history. Silly

accusations of witchcraft by some mischievous girls in Puritan dress gradually take possession of

Salem. Before the play is over good people of pious nature and responsible temper are

condemning other good people to the gallows.

Having a sure instinct for dramatic form, Mr. Miller goes bluntly to essential situations. John

Proctor and his wife, farm people, are the central characters or the play. At first the idea that

Goodie Proctor is a witch is only an absurd rumor. But "The Crucible" carries the Proctors

through the whole ordeal - first vague suspicion, then the arrest, the implacable, highly wrought

trial in the church vestry, the final opportunity for John Proctor to save his neck by confessing to

something he knows is a lie, and finally the baleful roll of the drums at the foot of the gallows.

Although "The Crucible" is a powerful drama, it stands second to "Death of a Salesman" as a

work of art. Mr. Miller had had more trouble with this one, perhaps because he is too conscious

of its implications. The literary style is cruder. The early motivation is muffled in the uproar of

the opening scene, and the theme does not develop with the simple eloquence of "Death of a

Salesman."

It may be that Mr. Miller has tried to pack too much inside his drama, and that he has permitted

himself to be concerned more with the technique of the witch hunt than with its humanity. For all

its power generated on the surface, "The Crucible" is most moving in the simple, quiet scenes

between John Proctor and his wife. By the standards of "Death of a Salesman," there is too much

excitement an not enough emotion in "The Crucible."

As the director, Jed Harris has given it a driving performance in which the clashes are fierce and

clamorous. Inside Boris Aronson's gaunt, pitiless sets of rude buildings, the acting is at a high

pitch of bitterness, anger and fear. As the patriarchal deputy Governor, Walter Hampden gives

one of his most vivid performances in which righteousness and ferocity are unctuously mated.

Fred Stewart as a vindictive parson, E.G. Marshall as a parson who finally rebels at the

indiscriminate ruthlessness of the trial, Jean Adair as an aging woman of God, Madeleine

Sherwood as a malicious town hussy, John Sweeney as an old man who has the courage to fight

the court, Philip Coolidge as a sanctimonious judge - all give able performances.

As John Proctor and his wife, Arthur Kennedy and Beatrice Straight have the most attractive

roles in the drama and two or three opportunities to act them together in moments of tranquillity.

They are superb - Mr. Kennedy clear and resolute, full of fire, searching his own mind; Miss

Straight, reserved, detached, above and beyond the contention. Like all the members of the cast,

they are dressed in the chaste and lovely costumes Edith Lutyens has designed from old prints of

early Massachusetts.

After the experience of "Death of a Salesman" we probably expect Mr. Miller to write a

masterpiece every time. "The Crucible" is not of that stature and it lacks that universality. On a

lower level of dramatic history with considerable pertinence for today, it is a powerful play and a

genuine contribution to the season.

March 30, 1984

Dustin Hoffman, 'Death of Salesman'

By FRANK RICH

s Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's ''Death of a Salesman,'' Dustin Hoffman doesn't trudge

heavily to the grave - he sprints. His fist is raised and his face is cocked defiantly upwards, so

that his rimless spectacles glint in the Brooklyn moonlight. But how does one square that feisty

image with what will come after his final exit - and with what has come before? Earlier, Mr.

Hoffman's Willy has collapsed to the floor of a Broadway steakhouse, mewling and shrieking

like an abandoned baby. That moment had led to the spectacle of the actor sitting in the

straightback chair of his kitchen, crying out in rage to his elder son, Biff. ''I'm not a dime a

dozen!,'' Mr. Hoffman rants, looking and sounding so small that we fear the price quoted by Biff

may, if anything, be too high.

To reconcile these sides of Willy - the brave fighter and the whipped child - you really have no

choice but to see what Mr. Hoffman is up to at the Broadhurst. In undertaking one of our

theater's classic roles, this daring actor has pursued his own brilliant conception of the character.

Mr. Hoffman is not playing a larger-than-life protagonist but the small man described in the

script - the ''little boat looking for a harbor,'' the eternally adolescent American male who goes to

the grave without ever learning who he is. And by staking no claim to the stature of a tragic hero,

Mr. Hoffman's Willy becomes a harrowing American everyman. His bouncy final exit is the

death of a salesman, all right. Willy rides to suicide, as he rode through life, on the foolish,

empty pride of ''a smile and a shoeshine.''

Even when Mr. Hoffman's follow- through falls short of his characterization - it takes a good

while to accept him as 63 years old - we're riveted by the wasted vitality of his small Willy, a

man full of fight for all the wrong battles. What's more, the star has not turned ''Death of a

Salesman'' into a vehicle. Under the balanced direction of Michael Rudman, this revival is an

exceptional ensemble effort, strongly cast throughout. John Malkovich, who plays the lost Biff,

gives a performance of such spellbinding effect that he becomes the evening's anchor. When Biff

finally forgives Willy and nestles his head lovingly on his father's chest, the whole audience

leans forward to be folded into the embrace: we know we're watching the salesman arrive,

however temporarily, at the only safe harbor he'll ever know.

But as much as we marvel at the acting in this ''Death of a Salesman,'' we also marvel at the play.

Mr. Miller's masterwork has been picked to death by critics over the last 35 years, and its

reputation has been clouded by the author's subsequent career. We know its flaws by heart - the

big secret withheld from the audience until Act II, and the symbolic old brother Ben (Louis

Zorich), forever championing the American dream in literary prose. Yet how small and academic

these quibbles look when set against the fact of the thunderous thing itself.

In ''Death of Salesman,'' Mr. Miller wrote with a fierce, liberating urgency. Even as his play

marches steadily onward to its preordained conclusion, it roams about through time and space,

connecting present miseries with past traumas and drawing blood almost everywhere it goes.

Though the author's condemnation of the American success ethic is stated baldly, it is also

woven, at times humorously, into the action. When Willy proudly speaks of owning a

refrigerator that's promoted with the ''biggest ads,'' we see that the pathological credo of being

''well liked'' requires that he consume products that have the aura of popularity, too.

Still, Mr. Rudman and his cast don't make the mistake of presenting the play as a monument of

social thought: the author's themes can take care of themselves. Like most of Mr. Miller's work,

''Death of a Salesman'' is most of all about fathers and sons. There are many father-son

relationships in the play - not just those of the Loman household, but those enmeshing Willy's

neighbors and employer. The drama's tidal pull comes from the sons' tortured attempts to

reconcile themselves to their fathers' dreams. It's not Willy's pointless death that moves us; it's

Biff's decision to go on living. Biff, the princely high school football hero turned drifter, must

find the courage both to love his father and leave him forever behind.

Mr. Hoffman's Willy takes flight late in Act I, when he first alludes to his relationship with his

own father. Recalling how his father left when he was still a child, Willy says, ''I never had a

chance to talk to him, and I still feel - kind of temporary about myself.'' As Mr. Hoffman's voice

breaks on the word ''temporary,'' his spirit cracks into aged defeat. From then on, it's a merciless

drop to the bottom of his ''strange thoughts'' - the hallucinatory memory sequences that send him

careening in and out of a lifetime of anxiety. Mr. Rudman stages these apparitional flashbacks

with bruising force; we see why Biff says that Willy is spewing out ''vomit from his mind.'' As

Mr. Hoffman stumbles through the shadowy recollections of his past, trying both to deny and

transmute the awful truth of an impoverished existence, he lurches and bobs like a strand of

broken straw tossed by a mean wind.

As we expect from this star, he has affected a new physical and vocal presence for Willy: a

baldish, silver- maned head; a shuffling walk; a brash, Brooklyn-tinged voice that well serves the

character's comic penchant for contradicting himself in nearly every sentence. But what's most

poignant about the getup may be the costume (designed by Ruth Morley). Mr. Hoffman's Willy

is a total break with the mountainous Lee J. Cobb image. He's a trim, immaculately outfitted gogetter in a three- piece suit - replete with bright matching tie and handkerchief. Is there anything

sadder than a nobody dressed for success, or an old man masquerading as his younger self? The

star seems to wilt within the self- parodistic costume throughout the evening. ''You can't eat the

orange and throw away the peel!,'' Willy pleads to the callow young boss (Jon Polito) who fires

him - and, looking at the wizened and spent Mr. Hoffman, we realize that he is indeed the peel,

tossed into the gutter. Mr. Malkovich, hulking and unsmiling, is an inversion of Mr. Hoffman's

father; he's what Willy might be if he'd ever stopped lying to himself. Anyone who saw this

remarkable young actor as the rambunctious rascal of ''True West'' may find his transformation

here as astonishing as the star's. His Biff is soft and tentative, with sullen eyes and a slow, distant

voice that seems entombed with his aborted teen-age promise; his big hands flop around

diffidently as he tries to convey his anguish to his roguish brother Happy (Stephen Lang). Once

Biff accepts who he is - and who his father is - the catharic recognition seems to break through

Mr. Malkovich (and the theater) like a raging fever. ''Help him!'' he yells as his father collapses

at the restaurant - only to melt instantly into a blurry, tearful plea of ''Help me! Help me!''

In the problematic role of the mother, Kate Reid is miraculously convincing: Whether she's

professing her love for Willy or damning Happy as a ''philandering bum,'' she somehow melds

affection with pure steel. Mr. Lang captures the vulgarity and desperate narcissism of the

younger brother, and David Chandler takes the goo out of the model boy next door. As Mr.

Chandler's father - and Willy's only friend - David Huddleston radiates a quiet benovolence as

expansive as his considerable girth. One must also applaud Thomas Skelton, whose lighting

imaginatively meets every shift in time and mood, and the set designer Ben Edwards, who

surrounds the shabby Loman house with malevolent apartment towers poised to swallow Willy

up.

But it's Mr. Hoffman and Mr. Malkovich who demand that our attention be paid anew to ''Death

of a Salesman.'' When their performances meet in a great, binding passion, we see the

transcendant sum of two of the American theater's most lowly, yet enduring, parts.

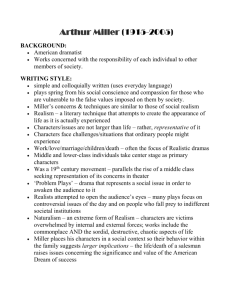

BIOGRAPHY

Arthur Miller (1915-2005)

American playwright who combined in his works social awareness with deep insights into

personal weaknesses of his characters'. Miller is best known for the play Death of a Salesman

(1949), or on the other hand, for his marriage to the actress Marilyn Monroe. Miller's plays

continued the realistic tradition that began in the United States in the period between the two

world wars. With Tennessee Williams, Miller was one of the best-known American playwrights

after WW II. Several of his works were filmed by such director as John Huston, Sidney Lumet

and Karel Reiz.

"Don't say he's a great man. Willy Loman never made a lot of money. His name was never in the

paper. He's not the finest character that ever lived. But he's a human being, and a terrible thing is

happening to him. So attention must be paid. He's not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an

old dog. Attention, attention must finally paid to such a person." (from Death of a Salesman)

Arthur Miller was born in Harlem, New York City; the family

moved shortly afterwards to a six-storey building at 45110th

Street between Lenox and Fifth Avenues. His father, Isidore

Miller, was an illiterate Jewish immigrant from Poland. His

succesfull ladies-wear manufacturer and shopkeeper was

ruined in the depression. Augusta Barnett, Miller's mother,

was born in New York, but her father came from the same

Polish town as the Millers.

The sudden change in fortune had a strong influence on

Miller. "This desire to move on, to metamorphose – or

perhaps it is a talent for being contemporary – was given me

as life's inevitable and righful condition," he wrote in

Timebends: A Life (1987). The family moved to a small frame house in Brooklyn, which is said

to the model for the Brooklyn home in Death of a Salesman. Miller spent his boyhood playing

foorball and baseball, reading adventure stories, and appearing generally as a nonintellectual. "If

I had any ideology at all it was what I had learned from Hearst newspapers," he once said. After

graduating from a high school in 1932, Miller worked in automobile parts warehouse to earn

money for college. Having read Dostoevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov Miller decided to

become a writer. To study journalism he entered the University of Michigan in 1934, where he

won awards for playwriting – one of the other awarded playwright was Tennessee Williams.

After graduating in English in 1938, Miller returned to New York. There he joined the Federal

Theatre Project, and wrote scripts for radio programs, such as Columbia Workshop (CBS) and

Cavalcade of America (NBC). Because of a football injury, he was exempt from draft. In 1940

Miller married a Catholic girl, Mary Slattery, his college sweetheart, with whom he had two

children. Miller's first play to appear on Broadway was The Man Who Had All The Luck (1944).

It closed after four performances. Three years later produced All My Sons was about a factory

owner who sells faulty aircraft parts during World War II. It won the New York Drama Critics

Circle award and two Tony Awards. In 1944 Miller toured Army camps to collect background

material for the screenplay The Story of G.I. Joe (1945). Miller's first novel, FOCUS (1945), was

about anti-Semitism.

Miller's plays often depict how families are destroyed by false values. Especially his earliest

efforts show his admiration for the classical Greek dramatists. "When I began to write," he said

in an interview, "one assumed inevitably that one was in the mainstream that began with

Aeschylus and went through about twenty-five hundred years of playwriting." (from The

Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller, ed. by Christopher Bigsby, 1997)

Death of a Salesman brought Miller international fame, and become one of the major

achievements of modern American theatre. It relates the tragic story of a salesman named Willy

Loman, whose past and present are mingled in expressionistic scenes. Loman is not the great

success that he claims to be to his family and friends. The postwar economic boom has shaken

up his life. He is eventually fired and he begins to hallucinate about significant events from his

past. Linda, his wife, believes in the American Dream, but she also keeps her feet on the ground.

Deciding that he is worth more dead than alive, Willy kills himself in his car – hoping that the

insurance money will support his family and his son Biff could get a new start in his life. Critics

have disagreed whether his suicide is an act of cowardice or a last sacrifice on the altar of the

American Dream.

WILLY: I'm not interested in stories about the past or any crap of that kind because the woods

are burning, boys, you understand? There's a big blaze going on all around. I was fired today.

BIFF (shocked): How could you be?

WILLY: I was fired, and I'm looking for a little good news to tell your mother, because the

woman has waited and the woman has suffered. The gist of it is that I haven't got a story left in

my head, Biff. So don't give me a lecture about facts and aspects. I am not interested. Now

what've you got so say to me?

(from Death of a Salesman)

In 1949 Miller was named an "Outstanding Father of the Year", which manifested his success as

a famous writer. But the wheel of fortune was going down. In the 1950s Miller was subjected to

a scrutiny by a committee of the United States Congress investigating Communist influence in

the arts. The FBI read his play The Hook, about a militant union organizer, and he was denied a

passport to attend the Brussels premiere of his play The Crucible (1953). It was based on court

records and historical personages of the Salem witch trials of 1692. In Salem one could be

hanged because of ''the inflamed human imagination, the poetry of suggestion.'' The daughter of

Salem's minister falls mysteriously ill. Reverend Samuel Parris is a widower, and there is very

little good to be said for him. He believes he is persecuted wherever he goes. Rumours of

witchcraft spread throughout the people of Salem. "The times, to their eyes, must have been out

of joint, and to the common folk must have seemed as insoluble and complicated as do ours

today." The minister accuses Abigail Williams of wrongdoing, but she transforms the accusation

into plea for help: her soul has been bewitched. Young girls, led by Abigail, make accusations of

witchcraft against townspeople whom they do not like. Abigail accuses Elizabeth Proctor, the

wife of an upstanding farmer, whom she had once seduced. Elizabeth's husband John Proctor

reveals his past lechery. Elizabeth, unaware, fails to confirm his testimony. To protect him she

testifies falsely that her husband has not been intimate with Abigail. Proctor is accused of

witchcraft and condemned to death.

The Crucible, which received Antoinette Perry Award, was an allegory for the McCarthy era and

mass hysteria. Although its first Broadway production flopped, it become one of Miller's mostproduced play. Miller wrote The Crucible in the atmosphere in which the author saw "accepted

the notion that conscience was no longer a private matter but one of state administration." In the

play he expressed his faith in the ability of an individual to resist conformist pressures.

"You know, sometimes God mixes up the people. We all love somebody, the wife, the kids every man's got somebody he loves, heh? Bus sometimes... there's too much. You know? There's

too much, and it goes where it mustn't. A man works hard, he brings up a child, sometimes it's

niece, sometimes even a daughter, and he never realizes it, but through the years - there is too

much love for the daughter, there is too much love for the niece." (from A View from the

Bridge)

Elia Kazan, with whom Miller had shared an artistic vision and for a period a girlfriend, the

motion-picture actress Marilyn Monroe, named in 1952 eight former reds, who had been in the

Communist Party with him. Kazan virtually became a pariah overnight, Miller remained a hero

of the Left. Two short plays under the collective title A View from the Bridge were successfully

produced in 1955. The drama, dealing with incestuous love, jealousy and betrayal, was also an

answer to Kazan's film On the Waterfront (1954), in which the director justified his naming

names.

In 1956 Miller was awarded honorary degree at the University of Michigan but also called before

the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Miller admitted that he had attended certain

meetings, but denied that he was a Communist. He had attended among others four or five

writers's meetings sponsored by the Communist Party in 1947, supported a Peace Conference at

the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, and signed many apppeals and protests. "Marilyn's fiance

admits aiding reds," wrote the press. Refusing to offer other people's names, who had associated

with leftist or suspected Communist groups, Miller was cited for contempt of Congress, but the

ruling was reversed by the courts in 1958.

Miller – "the man who had all the luck" – married Marilyn Monroe in 1956; they divorced in

1961. At that time Marilyn was beyond saving. She died in 1962.

In the late 1950s Miller wrote nothing for the theatre. His screenplay Misfits was written with a

role for his wife. The film was directed by John Huston, starring Mongomery Clift, Clark Gable,

and Marilyn Monroe. Marilyn was always late getting to the set and used heavily drugs. The

marriage was already breaking, and Miller was feeling lonely. John Huston wrote in his book of

memoir, An Open Book, (1980): "One evening I was about to drive away from the location –

miles out in the desert – when I saw Arthur standing alone. Marilyn and her friends hadn't

offered him a ride back; they'd just left him. If I hadn't happened to see him, he would have been

stranded out there. My sympathies were more and more with him." Later Miller said that there

"should have been more long shots to remind us constantly how isolated there people were,

physically and morally." Miller's last play, Finishing the Picture, produced in 2004, depicted the

making of Misfits.

Miller was politically active throughout his life. In 1965 he was elected president of P.E.N., the

international literary organization. At the 1968 Democratic Party Convention he was a delegate

for Eugene McCarthy. In 1964 Miller returned to stage after a nine-year absence with the play

After the Fall, a strongly autobiographical work, which dealt with the questions of guilt and

innocence. The play also united Kazan and Miller, but their close friendship was over, destroyed

by the blacklist. Many critics consider that Maggie, the self-destructive central character, was

modelled on Monroe, though Miller denied this. A year after his divorce, Miller married the

Austrian photographer Inge Morath (1923-2002), whom he had met during the filming of The

Misfits. Miller co-operated with her on two books about China and Russia. After Inge Morath

died, Miller plannd to marry Agnes Barley, a 34-year-old artist. In 1985 Miller went to Turkey

with the playwright Harold Pinter. Their journey was arranged by PEN in conjunction with the

Helsinki Watch Committee. One of their guides in Istanbul was Orhan Pamuk.

In the 1990s Miller wrote such plays as The Ride Down Mount Morgan (prod. 1991) and The

Last Yankee (prod. 1993), but in an interview he stated that "It happens to be a very bad

historical moment for playwriting, because the theater is getting more and more difficult to find

actors for, since television pays so much and the movies even more than that. If you're young,

you'll probably be writing about young people, and that's easier -- you can find young actors -but you can't readily find mature actors." ('We're Probably in an Art That Is -- Not Dying' , The

New York Times, January 17, 1993) In 2002 Miller was honored with Spain's prestigious

Principe de Asturias Prize for Literature, making him the first U.S. recipient of the award. Miller

died of heart failure at home in Roxbury, Connecticut, on February 10, 2005.

Notes for Arthur Miller's play Death of a Salesman

BEFORE YOU READ THE PLAY CONSIDER:

This Hypothetical Scenario

You are a senior at Clockwork High School. Clockwork High asks every student to pay a

$750 activity fee whether the student participates in a sport or activity or not.

When you first came to Clockwork High your goal was to be a player on the highly

regarded basketball team. The basketball team at Clockwork is extremely competitive and

you did not make the team in your freshman year. The coach however let you play with the

team and you came early to every practice and stayed late to help clean up.

You thought about playing baseball in the spring but you found out that the coach

liked his players to play in a non-school spring league to hone their skills and show their

dedication, so you forgot about baseball and played in the basketball spring leagues. You

worked hard all summer and went to a basketball camp. In sophomore year you made the

team as the second string point guard and back-up shooting guard.

Again you came early to practice and stayed late, played in the spring and went to

basketball camp. In junior year your body and your skill formed the perfect mesh. You

became the starting point guard and had an All-State year, scoring more points and making

more assists than any other guard in your conference. In the final playoff game of the year

you drove toward the basket but your foot went one way any your body went the other

twisting your knee until you heard a pop. Season over.

Rehabilitation of the knee goes well and you work harder than ever to gain your

strength back, but the knee remains weak and you have lost your once heralded speed. When

senior year begins you can still play well, but you can’t be the starting guard. The coach

comes to you and tells you that while you and the other guards are about equal in talent,

they are a freshman and a sophomore and he has decided to cut you. The younger players

need experience, they will play next year, and you won’t get much better during this, your

last season. You have played your last competitive game of basketball and didn’t know it.

Other teams, like baseball, don’t want seniors joining their team for the first time since it

throws off the team chemistry and causes resentment.

How do you feel about what has happened and the decisions that have been made by

your coach?

Motifs and Themes

"Kid"

Watch how often the the idea of "Kid," and "Boy," and "When are you going to grow up?" is tossed

around in the play. Biff, talking to Hap about himself, says that he sees himself as just a boy. "I'm

like a boy. I'm not married. I'm not in business, I just--I'm like a boy." Willy warns Biff not to use

the word "Gee" because "Gee" is a boy's word (The next morning, Willy will say "Gee whiz" to

Linda). Later in the play, Howard will call Willy "Kid." This patronizing attitude must add to

Willy's own insecurity. He seems sensitive to slights of this kind and therefore might use it as a

kind of warning to Biff or maybe he uses it as an unconscious attack, the kind where the victim

becomes the victimizer. This insecurity about his immaturity (even at the age of 63) is highlighted

by how angry Willy gets when Charley asks him in Act II, "When are you going to grow up?"

Poetry

Arthur Miller's language can be problematic for some people. There are lines that just don't ring

true or seem realistic. Linda talks about what she finds behind the fuse box: "And behind the fuse

box--it happened to fall out--was a length of rubber pipe--just short." What is this supposed to

be? What is Willy supposed to do with this rubber pipe that would kill him, breathe in gas? The

moment he became unconscious, the pipe would fall out of his mouth. The fact is that it does not

matter. It is the image of the rubber pipe and the gas that counts. The image expresses the

concept of suicide and that is all Miller needs for the audience to understand.

Another example of unrealistic or stylized language is the lies that the members of the family tell

each other about their past or even their present situations. These lies don't hold up under the

least bit scrutiny, even for these people. It is not the actual lies that they tell, but the image that

they convey. The boys and Willy tell lies. That is the important concept for the audience to gather

in. When the playwright tries to give an impression of reality rather than reality itself, it is a

matter of style and thus is considered "stylized." You will notice this in some movies and

television shows. Sometimes the scenery or the language is obviously fake or unreal. Didn't the

director notice? Of course she did. Look at the television shows Hercules or Xena: Warrior

Princess. Their costumes and language are way too modern for the time they are supposed to

inhabit, but the show still conveys enough about the setting for the audience to get the idea that

it happens sometime in the mythical past. The directors are showing a bit of style in their

presentation. Other examples of stylized settings are the films Moulin Rouge and the modern

Romeo + Juliet directed by Baz Luhrman.

Just as the scenery in Death of a Salesman is designed so that there is only enough of the house to

give the image of a dwelling that exists under the dominance of the apartment buildings, the

dialogue is written so that there is just enough story to give a hint of the major events in the lives

of the Loman family. The play is not meant to be reality. It is meant to convey an image or view of

reality. In the same way Pablo Picasso paints pictures that are not realistic yet comment on the

reality of our lives, so does Miller create a world that that cannot exist in reality but casts an

image that exposes truths about reality.

Act One

Willy and Linda

o

Willy, seemingly out of no where, asks, "How do they whip cheese?" While this might

appear to be a random remark, it is important to note that the playwright has only two or

three hours to reveal the important facts in this family's life. Nothing can be wasted with

such a task. Therefore nothing should be random, but rather all of the dialogue should be

calculated to reveal. If you are aware that you have a great play in front of you, your task is

to figure out what is the purpose of each minute of the play. In the case of the whipped

cheese, Tom B., Class of '04, points out that it indicates Willy's surprise at change. Willy is

amazed at changes in people, technology, home and neighborhood. This will be a major

theme during the play. Here in the first act, Willy bemoans the change in the

neighborhood and how the elm trees that were in the lot next door were cut down to put

up an apartment building. Now he feels boxed in and indeed the script indicates that the

buildings surrounding the Loman home loom over them just as Willy feels that the society

he doesn't fit into looms over him..

Happy and Biff in the room together:

o

o

Biff talks to Happy about coming out West with him. For a time, Happy is enthralled with

the idea. "That's what I dream about, Biff." Happy abruptly kills the dream that makes him

happy by asking about the kind of money a person could make out West. The dream that

makes him happy, Happy won't pursue. The dream about money and possessions that

offers no satisfaction for him, is the only one Happy pursues.

Happy talks about women and reduces them to objects. "I get that anytime I want, Biff.

Whenever I feel disgusted." With what is Happy disgusted? Later he says to Biff that he

wants somebody with "resistance." What does he want her to resist? Who is it that Happy

really does not like?

Willy's memory with the boys:

o

o

o

o

o

o

Why does Happy continually tell his father he is losing weight?

What is Willy's reaction to Biff's "borrowing" the football?

How do the boys treat Willy?

Why does Willy think Bernard will fail and Biff will succeed?

What kind of future does Biff have before him at this point?

Why, as Willy tells his boys, will Charley not succeed?

Willy's memory with Linda:

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

How does Willy's attitude change with Linda? Has he been as successful as he has

indicated to the boys?

How does Linda feel about him?

How does Willy feel about his appearance?

What does Willy envy about Charley? What does this say about what he has told the boys?

Willy displays a tremendous amount of self doubt. Why do you think he values being

"well-liked"?

Who is the woman in the hotel room? Give several reasons for Willy to be there with her.

Why does Willy get mad about Linda mending stockings?

Ben:

o

o

o

o

How old was Willy when Ben left? Did Willy ever have a chance to go off with Ben?

What was Ben's reason for setting off for Alaska? Why should Willy feel he lacks a role

model for fatherhood?

What did Willy's father do? Why is Willy a salesman?

Willy asks Ben what Willy should teach them. What is Ben's answer?

Linda speaks to the boys:

o

o

o

o

o

During this scene Linda shows pure, unconditional love for Willy.

Linda knows who her sons have become. She is not fooled, though she loves them.

Linda tells the boys that Willy has been trying to kill himself.

"There's a rubber pipe, just short." Don't be concerned with how the pipe works. It is a

symbol of his desire for death.

Linda takes it away, but she puts it back. Why does she put it back?

Biff speaks to Linda (with Happy in the room):

o

o

"He threw me out of the house." Have you guessed why Willy and Biff are in such great

conflict?

"Because we don't belong in this nuthouse of a city! We should be mixing cement on some

open plain, or -- or carpenters." Biff is displaying the self knowledge that he just can't

seem to hang on to. Willy, who built the ceiling in the kitchen, the porch, and did the

work on the house, should have been a carpenter.

Act Two

Howard's Office:

o

o

o

o

What does the tape recorder represent? Is it a symbol for anything?

Dave Singleman is the salesman who at the age of eighty-four made his living. It is this

image that convinced Willy to follow the career of sales. Willy is helped by his background

where his father did the same thing when he was a boy.

It is Dave Singleman who died the death of a salesman. What was that?

"You can't eat the orange and throw the peel away--a man is not a piece of fruit!" Can

anyone make a case for this being the central quote of the play?

I want all of my students to remember this quote. Workers, people, are not commodities.

They are not meant to be used up and then disposed of. When you are the person in

charge, the owner of a great company or an officer in a small one, when you are the

foreman or the boss, please remember that, while you have the responsibility of the

company to think of, you are an advocate for humanity. This is one of the most

important roles you will ever have, so remember to fill it with all your wisdom and

compassion.

o

What does it mean for Howard to repeatedly call Willy, "Kid"?

Willy Meets with Bernard:

o

o

o

o

How has Willy's opinion of Bernard changed?

Willy asks Bernard, "What happened?" So answer the question, what happened?

Bernard relates that Biff had gone to find Willy in New England. When Biff came back,

Bernard knew that Biff had given up his life. What happened in Boston?

Is this revelation about Willy and Biff significant enough to motivate or initiate all of the

subsequent action in their lives? This is an important question for you.

At the Restaurant:

o

o

o

o

o

o

Biff realizes the truth about his life. He was a shipping clerk for Bill Oliver. Oliver never

knew who he was. Everything that Biff told himself was a lie .

Why does Biff steal the fountain pen? (Please note that the value of a good fountain pen

would have been significant.)

Willy repeats his refrain: "The woods are burning." What does this mean to him?

In this family lies feel better than truth. (Remember The Matrix. Do you want the blue pill

or the red pill?)

Biff pleads with Happy: "Help him. Help him. Help me. Help me." Why does Biff link these

two ideas?

Happy says to the girls: "That's not my father. That's just some guy I know." What does

this tell you?

At Home:

o

o

Linda has finally had it with her boys.

Biff, in his climactic speech, tries to get Willy to understand that what is destroying them

is the dream. "I saw the things that I love in this world. The work and the food and time to

sit and smoke. . . . Why am I trying to become what I don't want to be? What am I doing

in an office, making a contemptuous, begging fool of myself, when all I want is out there,

waiting for me the minute I say I know who I am!" Why is it important for a person to

accept who he really is? For another take on this theme, see the movie On the Waterfront.

To Ben:

Who does Ben represent? What is he a symbol for?

The following article helps explain the flashback technique.

February 6, 1949

Arthur Miller Grew in Brooklyn

By MURRAY SCHUMACH

Such a commonplace, Mr. Miller explained the other night at a hotel here, is the theme of "Death of a

Salesman." The motif is the growth of illusion until it destroys the individual and leaves the children to

whom he transmitted it incapable of dealing with reality. "Every man," said Mr. Miller, "has an image of

himself which fails in one way or another to correspond with reality. It's the size of the discrepancy

between illusion and reality that matters. The closer a man gets to knowing himself, the less likely he is to

trip up on his own illusions."

Elaborating on this theme, he forgot temporarily the fatigue of rehearsal revisions and pre-opening

tensions that had scooped deep hollows from his high cheekbones to jutting jaw. His New Yorkese

became more pronounced with increasing enthusiasm.

Then, matter-of-factly, Mr. Miller turned to an analysis of the play's technique. The tragedy has two

concurrent themes that are maneuvered by flashbacks until they collide in climax. Generally speaking,

one theme delves into the past of the salesman, tracing his development and that of his family. The other

theme handles the present.

"This was the play where I decided not to be hampered by the iron vise of plot," he said. "I've always

been impatient with naturalism on the stage. But I knew I had to master naturalism before I tried anything

else. 'All My Sons' was in that category. The pattern I used for 'Death of a Salesman' gives me more

leeway for honest investigation and makes the people seem more lifelike. Of course, I think this play has

more roundness of truth and handles a great many more aspects of people. I guess it has more pity and

less judgment than there was in 'All My Sons.'"

Suddenly he stopped talking and his gaunt face became boyish as he grinned almost sheepishly. It is a

slow, wide grin that usually accompanies his proud comments on his two children, his wife's mastery of

the family exchequer or the behavior of his new convertible. He slid deep into his chair, stretched his long

legs over another chair and closed his eyes.

"Dammit, " he muttered wearily, "I hate living in hotels."

Mr. Miller dislikes living anywhere that cuts him off from the life of the average family. That is why his

home is in Brooklyn and why each year he spends a few weeks working in a factory. "Anyone who

doesn't know what it means to stand in one place eight hours a day," he said, "doesn't know what it's all

about. It's the only way you can learn what makes men go into a gin mill after work and start fighting.

You don't learn about those things in Sardi's."

Virtually everything Mr. Miller put into "Death of a Salesman" came from the writer's experiences or

observations. The one-family house Jo Mielziner used for a set is the model of countless such homes in

Brooklyn where Mr. Miller grew up after moving to Flatbush from Harlem as a boy. The salesman was

modeled on the fast-talking specimens he had seen so often because his father made coats. He know how

an adolescent can behave as a football hero because he played end at Abraham Lincoln High School in

Brooklyn until his knees were banged up so badly he couldn't get into the Army.

Mr. Miller's acquaintances, who judge him by his intense face and writings, are surprised to learn he is

not a born bookworm and that he spent his boyhood and most of his adolescence ignoring books for

sports. The change came suddenly in his senior year at high school, when he read Dostoievsky's "The

Idiot" and decided he had to be a writer. Thereafter, though he held tiring jobs as a truck driver, waiter,

crewman and a tanker, he used his spare time to read.

His first play, a three-acter, was written at the University of Michigan in a week and won for him a $500

prize. That award, plus the confidence of a fellow student, Mary Slattery, whom he later married,

convinced him his writing should take the form of plays. He stuck to this idea fairly steadily, though there

were years when his wife's salary as a secretary brought more income than his radio play scripts.

Only once did Mr. Miller lose faith. That was in 1944 after his first Broadway play, "The Man Who Had

All the Luck," flopped. He decided to try a novel and came up with "Focus." While this taut study of

domestic anti-Semitism and fascism was selling 90,000 copies Mr. Miller turned out "All My Sons," a

tale that had been kicking around in the back of his head.

Mr. Miller's pieces invariably fatten in his skull for a while before he begins writing. He is not of the

notebook school of writing. Nor does he subscribe to the theory that a man should get behind a typewriter

for a set number of hours every day, even if unaware of any ideas. In the case of "Death of a Salesman"

the idea came one day "the way marble comes in a solid block if you hit it right." But once under way he

works from 9 A.M. to 1 P.M. every day with a couple of more hours of production in the evening "that I

usually throw away the next morning."

Regardless of Broadway's reception of his play, Mr. Miller is sure of two things. He'll head for his

Connecticut retreat and relax in manual labor. And he'll continue to resist Hollywood: "I didn't go to

Hollywood when I was poor," he says, "why should I do it now?"

Mr. and Mrs. Miller left the apartment late yesterday for an undisclosed destination.