Guantanamo Bay Aff – HSSB

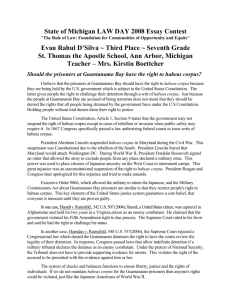

advertisement