Epistemology 1

advertisement

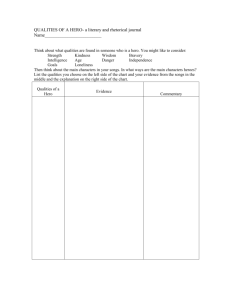

Epistemology “Theory of Knowledge” Traditionally divided into two categories A. Rationalism B. Empiricism Rationalism: Those who assert that by reason alone we can discover knowledge I. The school emphasizes that our “senses” cannot give any certain knowledge II. True knowledge is already within our minds in the form of “innate ideas” which we do not acquire, but are born with III. Plato and Descartes are examples of Rationalism Empiricism: Those who assert that we obtain knowledge solely by our senses I. Empiricism has usually developed in countries where the dominant interests have been practical and worldly (US and Great Britain) II. Modern Empiricism grew out of the philosophical struggles in 17th century England, when that country was rapidly developing, commercially and industrially III. Roger Bacon, John Locke, George Berkley, and David Hume are examples Plato (Aristocles) Writings I. Socratic Period: A. The Apology: contains account of Socrates’ speech in defense of himself at his trial B. The Crito: A Platonic defense as being a loyal citizen of Athens C. The Euthyphro. The Laches, and the Charmides: discusses the ideas of goodness and prudence D. The Protagoras: discusses virtue and its teachability E. The two Hippias (the Major and Minor): seen as a spirited erotic tale: the Major attempts to understand the concepts of “beauty” II. The Transition Period A. The Lysis: treats the concept of “friendship” B. The Cratylus: devoted to the philosophy of language C. The Euthdemus: directed against the logical fallacies of some of the later Sophists D. The Menexenus: discussion of Sohistic rhetoric III. The Period of Maturity (theory of “ideas” being developed) A. The Meno: again takes up the teachability of virtue B. The Phaedo: doctrines of ideas and immortality of the soul are interwoven C. The Symposium: the theory of “Ideas” applied to the realm of the “beautiful” D. The Republic: rests on same dualism as The Phaedo, concerned with this world and its problems, contains material on ethics, the “Allegory of the Cave”, and the myth of the fate of the soul E. The Phaedrus: (Once regarded as first work of Plato), a work on love and Eros ; contains OrphicPythagorean theory of transmigration of souls The Works of Old Age A decline in Ontology I. The Parmenides: Socrates defending himself against a series of criticisms of the theory of ideas by Zeno and the Eleatic School II. Theatetus: epistemelogical concerns on theory of “ideas” III. The Sophist: a continuation of The Theaetus, main attack is the Sophists IV. The Statesman: views the true ruler as the “Knower” who alone possesses truth—enlightened despotism V. The Philebus: a short discussion on the “one and many”, shows relationship of pleasure to the good VI. The Timaeus: the only dialogue concerning natural science—contains a theory of creation VII. The Critias: discusses the ideal agrarian state projected onto the earliest days of Athens VIII. The Hemocrates: describes the degeneration from the original ideal state to the present IX. The Laws: (last work), basic concepts of The Republic are reemphasized, some concessions to “real life” PlaTo’s ePisTemelogy I. Cannot be found systematically in any one work II. The Theaetetus —considers knowledge, conclusion is negative A. Knowledge is not senseperception B. Knowledge is not simply “true judgment” C. Knowledge is not true judgment plus an “account” D. Characteristics of true knowledge 1. infallible 2. of the real Theory of Form or “Ideas” I. Knowledge is related to the good, but not the good itself II. Knowledge is in the eternal realm of the essences III. There is a world of being (Parmenides)—unchanging ideals IV. There is also the world of becoming (Heraclitus)—everchanging V. There is a third realm (The Timaeus) called space VI. An interpretation of the theory of ideas A. Any attempt to reduce it to a principle and interpret it as a whole is futile B. The concept of the idea must not be interpreted as being a subjective concept in the mind— it has an objective reality C. Ideas have a three-fold significance 1. Ontological—in that they represent real being 2. Teleological—all ideas have ends and aims to their being 3. Logical—the ideas enable us to bring order into the chaos of Individual beings D. The ideas exist in a sphere apart from our reality 1. The Phaedo teaches that the soul existed before its union with the body in a transcendental realm 2. The process of knowledge consists essentially in recollection 3. God or the “demiurge” form things of this world according to the model of the Forms E. The Philebus, there is a strong Pythagorean influence 1. Nature is reality is numbers 2. Uses Pythagorean opposites 3. Origin of Ideas is the One Allegory of the Cave I. Found in Book 7 of The Republic II. Knowledge advances by stages A. From sense perception it proceeds to pure thought (pure mathematics) B. From pure thought is proceeds to the idea (mathematical knowledge to dialectical science C. From the ideal to the realm beyond (from ideas to the Good) III. The allegory shows the ascent of the mind from the lower sections to the higher as an epistemological progress A. Prisoners represent the majority of humankind B. We live in a world of shadows C. The view of the world is distorted by the shadows D. We cling to our distorted views IV. The cave also represents the importance of proper education Descartes (1591-1650) I. Cartesian Doubt A. Considered to be the “founder” of modern philosophy— first philosopher to allow the new physics and astronomy to effect his philosophical system II. During the Thirty Years’ War (1619) in Bavaria he had a dream in which he said “the spirit of Truth” opened to him “the treasures of all the sciences” A. He recorded this incident in Discourses on Method (1637) B. Second major work is the Meditations (1642) 1. In the Meditations he preaches the “duty of doubt” 2. Wanted to go beyond the senses to beginning of knowledge 3. In the Second Meditations he uses “wax” as an example of how our senses deceive us 4. By concentrating only on what he knew for certain, he began what we know as “Cartesian doubt” C. The methodology of “Cartesian doubt” 1. Begins by doubting everything that he could manage to doubt a. First begins doubting senseexperience b. What thing I cannot doubt is my own experience “While I wanted to think everything false, it must necessarily be that I who thought was something; and remarking this, I THINK THEREFORE I AM, was so certain that all most extravagant suppositions of the skeptics were incapable of upsetting it. I judged that I could receive it without scruple as the first principle of the philosophy that I sought” 2. Having set a secure foundation, he sets to work to rebuild the edifice of knowledge a. “I am a thing that thinks” b. My existence is different from the physical world; that the soul is wholly distinct from the body c. Why was the Cogito so evident? Because it is “clear and distinct”—thus, all things that we conceive clearly and distinctly are true d. He deals with knowledge of our bodies—here he uses the example of wax e. Proving the existence of an External World can be done only by proving the existence of God 3. His Proof of God’s existence (A revision of Anselm’s Ontological Argument” a. Everything has a cause (including our ideas) b. We have an idea of God c. Nothing less than God is adequate to cause our idea of God 4. Besides the ideas of self and God, there was another set of ideas which were seen to be innate without any reference to the external world—the truth of mathematics 5. All other knowledge comes to us us from the outside world III. Empirical Emphases A. Descartes realized that one could proceed by deduction only a short distance from the apex of a pyramid B. A deduction from intuitively self- evident principles is of a limited usefulness in science—it would yield only the most general of laws C. He also posited a belief that one cannot determine from a mere conclusion of general laws, the cause of physical processes D. For one to be able to deduce a statement about a particular effect, it would be necessary to include among the premises information about the circumstances under which the events occur E. An important tool for observation and experimentation is to provide knowledge of the conditions under which events of a given type takes place IV. Primary Qualities and Secondary Qualities A. In his doubting process he had to prove what is clear and distinct about a physical object—he would use a lump of wax as an example 1. We understand the “real nature” of wax through “intuition” 2. Such “intuition” is to be distinguished from the sequence of appearances 3. He would distinguish between those “primary qualities” which all bodie must possess and “secondary qualities” which exist only in the perceptual experience of the subject B. He believed that God created a universe of “infinite extension” (thus, no vacuum) and “motion”—science thus reduced to measurement and mathematics 1. All change must come through motion 2. Motion could neither increase nor decrease, but only transferred from one body to another 3. The universe continues to run as a machine and each body persists in a state of motion in a straight line; the geometrically simplest form in which God set it going, unless acted on by an external force V. General Scientific Laws A. From his understanding of extension, he would develop several important physical principles B. He seemed to believe that because the concepts of extension and motion and clear and distinct, certain generalizations about these concepts must be considered as a priori truths 1. One generalization is that all motion is caused by impact or pressure due to his belief that no vacuum can exist, thus every entity must be touched by another entity 2. However, he denied the possibility of action-at-a-distance in an effort to defend a thorough-going mechanistic view of causation 3. Such a view would be revolutionary in his day— this belief would be a denial of magnetism and gravity 4. Another generalization is derived from the idea of extension is that all motion is a cyclical rearrangement of bodies; if one body changes its “location”, a simultaneous displacement of others bodies is necessary to prevent a vacuum C. Descartes wrote that God is the ultimate cause of motion—a perfect being would create a universe “all-at-once” and this perfect being would keep motion going, otherwise the universe would run down Empiricism John Locke Essay Concerning Human Understanding I. He attempts to show how various concepts or ideas come from or are built up from different kinds of experience II. Denial of Innate Ideas—there are no principles or ideas that we have any reason to believe we have prior to, or independent, of our sense III. The White Paper (Tabula Rosa), Locke believed that our minds are like a white paper—void of all characters, without any ideas IV. Two sources of knowledge— perception and reflection IV. Simple Ideas 1. Simple ideas are the most basic of our knowledge 2. Simple ideas are presented to us in sensation and reflection 3. Once the mind experiences simple ideas, it has the power to store up, to repeat, and to combine them V. Primary and Secondary Qualities A. Primary qualities are those items in our experience which must belong to the objects that we are B. Secondary qualities are nothing in the objects themselves, but powers to produce various sensations in us by primary qualities, e.g., color VI. Kinds of knowledge A. Discussed in the Fourth Book of the Essays, how reliable can knowledge of sensation and reflection be? B. Our knowledge is the result of the examination of ideas it see if they agree or disagree in some respects—four kinds 1. First kind is achieved by the inspection of two or more ideas to see if they are identical or different 2. Second kind is the discovery that two or more ideas are related together in some manner 3. Third kind is about ideas which deals with the coexistence of two or more ideas belonging together 4. Fourth kind of knowledge is the discovery of whether or not any of our ideas are experiences of something that exist outside of our minds, i.e., if they are of some real existence VII. External Reality A. In order to keep his theory of knowledge from ending to calling knowledge one’s person’s experience based on one’s observations, he attempted to show that even with our limited knowledge gained from experience we have some basis for claiming that we know something about what goes on outside of our minds B. The Mind is incapable of inventing simple ideas—thus they must be the result of something outside of our minds VIII. His view on prospects and limitations of science are found in his Essay A. He had a view accepting a primitive concept of atoms, thus in order to be able to “predict” mechanical behavior one would need to: 1. Know the configurations and motions of atoms 2. Know the ways in which the motion of atoms produce ideas of primary and secondary qualities in the observer 3. If these two conditions were met, then one would know a priori that certain properties would be identified with entities B. However, we are ignorant of the configuration and motion of atoms 1. This ignorance is contingent 2. Know the ways in which the motion of atoms produce ideas of primary and secondary qualities in the observer 3. But, we still could not reach a necessary knowledge of phenomenon since we are ignorant of the ways in which atoms manifest certain powers C. The atomic constituents of a body possesses the power through motion, to produce in us ideas of secondary qualities such as colors and sounds D. Also, the atoms of a particular body have the power affect the atoms of other bodies so as to alter the ways in which these bodies affect our senses E. Only by “divine revelation” could we know the ways in which atomic motions produce effects on us F. He also held that an unbridgeable epistemological gap separates the “real world” of atoms and the realm of ideas that constitute our experience IX. He recommended a methodology of correlation and exclusion for scientific investigation based on a compilation of extensive natural histories A. This understanding involved a shift in focus from “real essences” (atomic configurations of bodies) to “nominal essences” (the observed properties and relations of bodies) B. He insisted that the most that can be achieved in science is a collection of generalizations about the association and succession of “phenomena” C. He somewhat “degenerated” natural science—a trained scientist may have judgment and opinion, not knowledge and certainty X. He did believe that there do exist necessary connections in nature— even though the connections are opaque to human understandings. A. The usage of the term “idea” was between gaps 1. “Ideas” are effects of operations in the “real world” of atoms 2. Thus, red is produced by processes external to the subject B. He was confident that the motions of atomic constituents of matter that give rise to our ideas of colors and taste—even though we cannot learn just how this takes place David Hume I. Carried British Empiricism to a skeptical blind alley A. By contending that belief in the identity of the self or objects in the external world was simply the result of a habit B. Identity is “nothing really belonging to these different perceptions and uniting them together; but it is merely a quality which we attribute to them because of the union of their ideas in the imagination.” II. In An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding he divided the perceptions of the mind into two classes A. Thoughts or ideas—the least forcible and lively—they are reflections of impressions B. Impressions—results from direct experience; what we see, hear, feel C. The creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting or diminishing the materials afforded us by our senses and experiences The Synthesis of Immanuel Kant I. He initiated a “Copernican Revolution” in philosophy A. Reaction to radical empiricism of David Hume B. Freed theology from corrosion of classical empiricism while maintaining rationality of religious belief II. Kant responded that Hume and the empiricists had a passive and dualistic view of cognition—which conceived of the mind as simply a receptor of particular sense impressions A. Kant emphasized that the mind is active—instead of beginning with the object as something already given to which the mind must conform, he reverses the order and conceives of the object as in some respect constituted by the a priori B. The mind imposes upon the material of experience its own forms of cognition, determined by the very structure of human understanding C. The raw material of experience is thus molded and shaped along certain definite lines according to the cognitive forms with the mind itself D. These forms of the mind are the way we “put things together” E. All experiences presuppose these a priori categories which are not themselves observable III. The cognitive forms of experience determine the possibility of objects of knowledge A. The categories of experience determine our knowledge of phenomena B. If the word object were taken to refer to “things-in-themselves”, things apart from any relation to a knowing subject, then we could not say they are known by the human mind C. We cannot, thus, know noumena, things- in-themselves, i.e., supersensible objects, for we lack the necessary cognitive organ IV. He looks at the nature of judgment of judgment in four ways A. Analytical judgment— (rational & deductive)—in which the predicate is contained within the subject and may be known by analysis of it, e.g., “bald men have no hair” B. Synthetical judgment (empirical & inductive)—one in which the predicate is not contained with the subject., e.g., “the rose is red” C. A priori judgment (rational)—one which asserts a universal and necessary connection, e.g., 2 + 2 = 4, always and must be, a judgment before the fact D. Post-priori judgment (empirical)—one which does not assert a universal and necessary connection— a judgment after the fact, e.g., “the rose is red” E. For Kant, the major question is whether there are synthetical, a priori judgments (i.e., those judgments in which predicates are not contained within the subject but are still universal and necessary)—he concluded there were—math is an example V. Kant gives two sources of knowledge A. Sensibility—the use of senses B. Understanding—the rational process of the mind