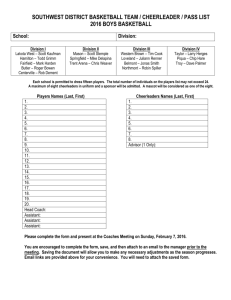

Division 6 - HSPA Foundation

advertisement