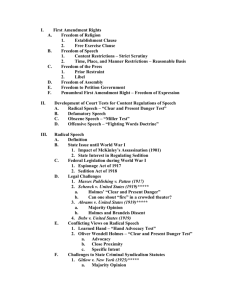

I. Constitutional Interpretation & the Judicial Role

advertisement