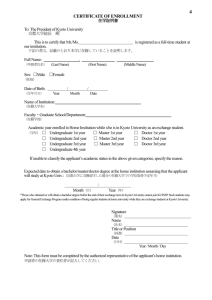

thesis

advertisement