Slater 04 - Open Evidence Project

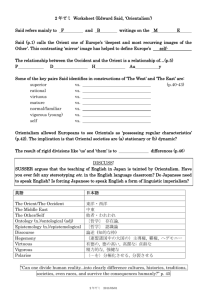

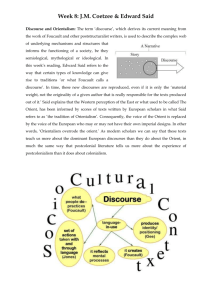

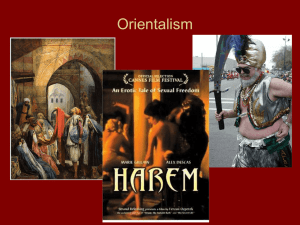

advertisement