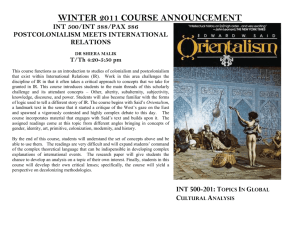

Orientalism Kritik - Open Evidence Archive

advertisement