Juveniles Tried As Adults

advertisement

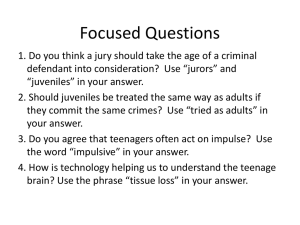

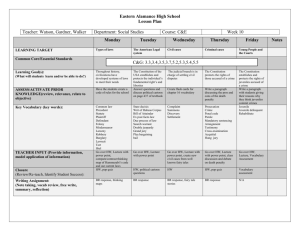

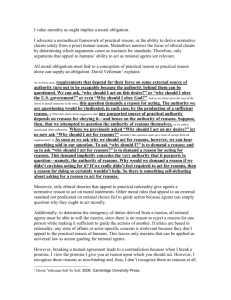

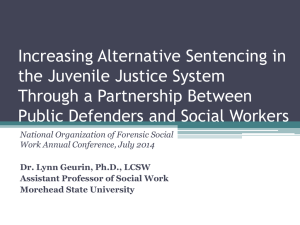

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO COLORADO SPRINGS Juveniles Tried As Adults: Disparities and Harshness of Youth Sentencing Stella Steele 5/6/2011 Abstract: In the early nineties America experienced a rising epidemic of teenagers committing violent crimes; as a result political decisions were made to increase harshness in sentencing. Legislation was enacted across most states to transfer juveniles to adult courts at younger ages based on crime severity. This review examines the circumstances for case transfers, ramifications of placing minors in adult prisons, sentencing disparities between juveniles and young adults. A content analysis was conducted and derived from internet media coverage of 30 Colorado teen cases involving murder or accidental deaths. Results indicate age as the primary factor for case transfer and severity of sentencing correlates with year of crime. Disparities in sentencing exist at multiple levels. Introduction of Literature Review The general belief in every society has been children do not possess equivalent emotional and mental abilities as adults; therefore any crimes committed should be handled with greater leniency. Over the past few decades our country has had a trend of treating juveniles as young adults and sentencing harsher punishment due to the severity of crimes conducted. The purpose of this literature review is to 1.) Compare sentencing between minors tried in juvenile court and those tried in adult court for same crimes 2.) Compare sentences issued to juveniles tried as adults versus young adults for equivalent crimes 3.) Discover the effects of placing juveniles in the same facilities as adult criminals. History The Hammurabi Code was the first to establish a written law enforcing children to be dealt with less harshly over 4,000 years ago. In the United States our first juvenile court was established in 1899 to provide the role of rehabilitation for children committing crime (Kurlychek & Johnson, 2004). During the 1980’s and 1990’s American’s started to see a rapid increase in juveniles committing violent crimes while crime rates for other groups were dropping (Kurleychek & Johnson, 2010). This gained much media and political attention; the publicized slogan became “If you’re old enough to do the crime, you’re old enough to do the time” and our nation embraced the concept. During the 1990’s 49 states and the District of Columbia changed legislation to increase the number of circumstances in which a juvenile could be tried as an adult. The decisions to transfer cases are based upon seriousness of the current offense along with any prior criminal history. Little regard is shown towards the defendant’s individual character or possible mitigating circumstances (Urbina & White, 2009; Kurlycheck & Johnson, 2004). As a result juveniles transferred to adult courts increased by 400 percent in the 80’s, state imprisonment of minors more than doubled between 1985 and 1997, and over 200,000 were tried as adults between 1996 and 1999 (Kurlychek & Johnson, 2004). Survey research has been conducted over the past ten years to gain public opinion regarding trying juveniles as adults. The conclusion shows 75% of respondents support juveniles being treated as adults for violent offenses (Myers, 2003). The question being addressed in light of this information is: Are they receiving equivalent sentences as young adults are being given? Additionally, what are the ramifications behind incarcerating juveniles with adult hardened criminals? The primary purpose for transferring youth committing serious and violent crimes is to assure harsher punishments which will hopefully provide deterrence and reduce recidivism rates (Urbina & White, 2009) (Myers, 2003). The following information examines sentences distributed to juveniles, juveniles as adults, and young adults. Juvenile in Adult Court vs. Juvenile Court Researchers originally argued harsher punishments were being distributed in juvenile courts than adult courts defeating intended purposes. Further studies however revealed that the severity of sentencing correlates with the type of offense. Offenders committing property crimes are treated more leniently receiving parole instead of incarceration; however violent crimes are given harsher jail or prison sentences (Myers, 2003). A study conducted by David Myers compared Pennsylvania juveniles waived to adult court with those remaining in the juvenile justice system for violent offenses in 1994. The results concluded: transferred juveniles had higher conviction rates; those convicted were likely incarcerated; once incarcerated longer periods of time were spent in confinement (Myers, 2003). The harsher sentencing does not appear to provide the desired results regarding deterrence. Florida and Pennsylvania studies show juveniles that were transferred to adult courts had higher recidivism rates with more serious crimes being committed than those tried in juvenile courts that went to reform school (Urbina & White, 2009). In Wisconsin 123 court officials participated in a study regarding juveniles processed in adult court rooms and only 40 viewed waivers as an effective tool for reducing recidivism (Urbina & White, 2009). Juvenile Adult Sentencing vs. Young Adult Sentencing Adult court judges view incapacitation of juveniles as being a necessary public safety measure because offending behavior peaks during late adolescence and begins declining in young adults. This rationalization leads to harsher sentencing for teens than offenders in their early 20’s (Kurleychek & Johnson, 2010). A criminal justice research study using data provided by the Maryland State Commission on Criminal Sentencing Policy found juveniles convicted of drug charges receive sentences six times harsher than adults. Overall sentencing is between 62% and 75% harsher for having a juvenile status in a Maryland adult court (Kurleychek & Johnson, 2010). A different study was conducted regarding juvenile felony defendants in 19 states showed of those convicted, 60% were confined to state prisons while only 43% of adults received equal punishment. In the 2004 study by Kurleychek and Johnson, the average offender in the Pennsylvania sample shows juveniles have a 10% greater likelihood of incarceration, a 29% increase in sentence length. Conclusion of Literature Review The data presented indicates a disparity in sentencing between juveniles, juveniles tried as adults, and young adults. Juveniles receive harsher punishments in adult courts for violent crimes; however sentencing is lighter for property crimes than those tried in juvenile courts. When comparing sentences given to juveniles versus young adults for similar crimes, juveniles receive longer and harsher sentencing. Society had hoped harsher sentencing would provide reduced recidivism but studies show opposite results. Additional consideration should be taken when confining youth and adult offenders in the same facilities. Juveniles in adult prisons experience higher rates of victimization by staff and inmates, higher suicide rates, and inferior treatment services than adult offenders. Juveniles also have greater psychological needs that cannot be dealt with adequately in adult incarceration facilities (Myers, 2003). Hypothesis Based on the literature review above and thinking about the disparities in courtroom process and sentencing between states, this research project will look closer at Colorado juvenile murder cases. In 1987 prosecutors in Colorado were given the power to direct-file anyone aged 14 and older to adult court if the crime was violent in nature. In the early 1990’s Colorado experienced a rise in murders and crimes resulting in death committed by juveniles which led to expanded direct file authority. By 1996 legislation passed which allowed parents to waive their right to be present while police interrogated their children. With the prosecution side of the criminal justice system, including police officers and district attorneys, having vast power at the forefront of juvenile violence cases, this research addresses the following hypotheses: 1) Nature of crime determines the majority of transfers to adult court and age is not a factor. 2) The timeline during which the crime was committed, and the county conducting the trial, affects years of punishment (severity). 3) Mitigating circumstances or lack thereof are not a factor in sentencing. 4) Disparities exist amongst the variables in aforementioned hypotheses. Methods Case Studies Cases included in this study are teenagers in Colorado that have been tried in adult court (23 cases) for committing crimes which have led to the death of another person. There are seven cases included of which the child was retained in juvenile court for basis of comparison in sentencing. Public records are sealed for those in juvenile court therefor only seven cases were found available in the media creating comparison limitations. The list of cases was compiled by Pendulum Foundation of teens who kill a parent or grandparent. Cases that included teens that were no longer minors have been excluded. If the juvenile had an accomplice, I included the additional case into the study if they were also a minor. The remaining cases were found by internet search engines using “juveniles tried as adults in Colorado” or similar phrases. I would gather any pertinent data from the numerous sites I located and input the data into an excel spread sheet. If the media provided sufficient information for this study it has been included. Once 30 cases were discovered, the minimum criteria for reaching statistical significance, I discontinued the search due to time constraints. Note: Due to the significant quantity of websites I gathered data from they have not been included in the appendix. (See Appendix B for additional demographic bars, charts, graphs relevant to case study analysis). Materials I used the list from Pendulum (appendix A), the website www.pendulumfoundation.org, and any online newspaper articles I could locate to obtain information including who committed the crime, the county with jurisdiction over the case, the age at the time of crime, the year of sentencing, circumstances behind the crime, and sentencing detail. If photos of the prosecuted were available then a visual observation was made to determine ethnicity of white or other, a process which provided further limitations. Procedures The information obtained above was utilized to determine any disparities in sentencing by comparing which county the trial was held, the quantity and severity of the crime/s committed, the year of sentencing in correlation with changes in public policy due to heightened crime, and any potential mitigating circumstances which may sway the judge’s discretion. The data compiled was coded (A) year of trial, (B) age when crime was committed, (C) Gender 1) male and 2) female, (D) county where the trial occurred, (E) tried as 1)juvenile or 2)adult, (F) primary charge by class of felony: Class 1 or 2, (G) secondary charge class 1-5, (H) quantity of crimes, and (I) sentence length in years. Variables utilized for qualitative analysis included (J) why the crime was committed, (K) who it was committed against, (L) severity of sentencing. Data was input into SPSS with multiple variables dichotomized, collapsed, or input by assigning numeric categories or scales to test for Measures of Central Tendency, Variability, and Association. The year of trial was collapsed to reflect crimes prior to 93’, between 93’ and 2000, and 2001- present. County was dichotomized with El Paso=0, other=1; and collapsed El Paso=1, Boulder=2, other=3. Sentence years was dichotomized to 0=40 years or less and 1=40+years. Crime detail was categorized by 1=killed parents, 2=killed sibling, 3=killed non-family member, 4=Injured/affected non-family. This later dichotomized to 0=killed/hurt family, 1=killed hurt non-family. Labeling why the crime was committed is as follows: 1) mentally ill, 2) sexually abused, 3)abused generally, 4)personal gain, 5)was an accomplice, 6)other/unknown. This category was further dichotomized to reflect 0=abused, 1 not abused. Results A Chi Square test ran for how a juvenile is tried (juvenile or adult) being dependent upon age with age 0-14 and 15-17 resulted in a 4.751 value, and Lambda at .273 value however 2 cells have less than an expected level of five (see appendix C ). No confirmation can be made regarding hypothesis 1. Sentence years is dependent upon age with χ2 (1)=5.792, p<.01. The statistical significance at .006 level indicates a 99% confidence level that we can apply the sample to the general population (appendix D). Knowledge of timeline when the trial occurred improves prediction of whether or not the juvenile was sentenced to < or > 40 years in prison and can be generalized to the population with significance at .019 level and a 99% confidence level and Correlation/Regression level of .396 (appendix E). Every county appears to have similar results in sentencing except for Boulder. Of the six cases that have been tried their only one individual was sentenced to a sentence of greater than 40 years. Sentenceyrs3 * County3 Crosstabulation County3 El paso Sentenceyrs3 40 years or less Count % within County3 over 40 years Count % within County3 Total Count % within County3 Boulder other Total 6 5 6 17 50.0% 83.3% 50.0% 56.7% 6 1 6 13 50.0% 16.7% 50.0% 43.3% 12 6 12 30 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% Timeline and living in Boulder affect the sentencing outcome in years therefore accepting hypothesis number 2. Discussion Limitations This study was performed on juveniles responsible for the death of another with only thirty cases included. Locating media regarding this topic which covers a thirty year span was more difficult than I anticipated. Many newspaper articles I attempted to locate are on micro-film and others have been archived. Time constraints did not allow for the period of time it would take to locate and receive copies. Lack of microfilm and archived copies made it difficult to locate information regarding race. Difficulty in finding media in general led it to be too time consuming to discover more than thirty cases. Further research would include a greater number of cases with female convictions, a more efficient process in discovering ethnic origin, and an addition of more cases from Boulder to compare to El Paso County. Lastly due to juveniles tried in juvenile court is held confidential therefor locating public media is nearly impossible. Qualitative Results Disparities One case included a juvenile (16 yrs. old) female who shot a man she accused of sexually assaulting her; she received two years’ probation in juvenile court. This is the only case of a person murdering another and receiving probation only. Two other juveniles were sexually and physically abused by their parents and killed them; both of them with accomplices, all parties have received life without parole. Although each scenario involved a person being abused and fighting back the outcomes are drastically different. This cross tabulation reflects sentence severity versus whether the individual suffered abuse: abuse * Sent.Severity Crosstabulation Sent.Severity Average abuse not abused Count % within Sent.Severity 2 Count % within Sent.Severity Total Count % within Sent.Severity Most Severe Severity of Least Severe Punishment Punishment Punishment Total 1 1 5 7 25.0% 14.3% 26.3% 23.3% 3 6 14 23 75.0% 85.7% 73.7% 76.7% 4 7 19 30 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% A case which was not included in this study involves a mother (18 years old) that left her child in a car all day with the windows locked in the summer. The child died of a heat stroke; the mother received probation and counseling as her final sentence. She claimed she simply forgot the child was there and negotiated her crime to child abuse resulting in accidental death. A sixteen your old female and her boyfriend (17 years old) beat her sister to death while playing a live version of mortal combat. The girl had a history of abusing her sister; their mother had a history of drug abuse and neglect; the boyfriend had a history of domestic violence against his girlfriend (the defendant). At the end of this court case the sister received a plea bargain of child abuse resulting in death. A sentence that carried 18 years in prison, however if 6 years were completed successfully in a juvenile correction center the remaining term would be suspended. Her boyfriend was tried fully as an adult and received a straight 36 year sentence. The mother received no charges against her regardless of leaving the youngest daughter alone with the oldest which had previously abused her. The final case I will use as an example is that of three teenagers attempting auto theft in the process shot the 16 year old car owner. No evidence was ever brought forth to prove which teen was the actual shooter. One teenager is spending life in prison without parole, the other two less than 40 years in prison. Interestingly the teenager which originally confessed to being the shooter is not the one sitting in prison for life. Conclusion The literature review indicated a disparity in sentencing between juveniles and young adults along with juveniles tried as adults versus those tried in juvenile court. This study reflects a disparity in sentencing between Boulder county, between multiple cases, and amongst one case with multiple defendants. There is no obvious correlation to how judges handle mitigating circumstances or to how age factors into the scenario. In order to have a justice system that is fair and equal we as a society must implement legislation which addresses the disparities in our courtrooms. Hypothesis number one is rejected due to lack of sufficient samples for testing. Hypothesis two is accepted because timeline and committing a crime in Boulder appear to be factors in determining if one is or is not spending over 40 years in prison. Hypothesis three is being accepted primarily due to the acceptance of hypothesis four. Disparities in sentencing make it difficult to find any consistent association with mitigating circumstances contributing to a final verdict. As noted the quantity of limitations in this research case leave room for improvement in future studies to aid in additional correlation findings. Appendix A SENTENCES OF COLORADO TEENS WHO KILL PARENT OR GRANDPARENT (Two teens who received life sentences highlighted in red.) (2010) 16-year-old Colorado Springs girl prosecuted in the fatal shooting of a man accused of sexually assaulting her. Prosecutors accepted a guilty plea of manslaughter. The case remained in juvenile court, where the girl faces two years of probation plus counseling when she is sentenced on May 25.” (2009) Jeremiah Raymond Berry, 22, pled guilty to manslaughter after shooting his 42-year-old father, Jack Berry, in the head, dismembering his corpse and feeding pieces to the coyotes. Father had been sexually abusing him. He will spend three years in prison and 10 years of intensive supervised probation after his release. (2007) Tess Damm, 15, and accomplice Bryan Grove,17, stabbed Damm’s alcoholic, abusive mother to death. Tess Damm pled to 23 years. Grove plea bargained to 40 years. (2005) John Paul Young killed his grandmother by shooting her in the head on April 26,2005. Pled guilty to reckless manslaughter. Originally charged as an adult with first-degree murder, but prosecutors decided a jury would likely have convicted him of reckless manslaughter. Sentenced to YOS for 2-5 years. In 2009, asked for an early release. (2004) Michael Fitzgerald, 16, killed his father. Pled to 62 years. Sent to a mental hospital. (2003) Thomas Martinez, 38, doused his father with kerosene, and set him ablaze with a cigarette lighter.Ernest Montoya, 58, died several weeks after the 2003 incident during his birthday party. Martinez pled guilty to second-degree murder; faces at least 16 years in prison with the possibility of parole in five years. (2004) Staci Lynn Davis, 13, pleaded guilty to shooting her mother to death at the Arapahoe Park Racetrack. She was sentenced to seven years in the state youth corrections system. (1999) John Engel, 14, convicted in the deaths of his mother and grandmother in the family's Longmont home on Dec. 11, 1999. Received 32 years, released after 8. A Boulder County judge reconsidered his sentence in 2008 and gave Engel a chance to finish his time in a community-based correctional program. Engel violated the terms of his new sentence, however, and was sent back to prison last year for 25 years. (1999) Jason Spivey, 17, faced life in prison if convicted in the sexual assault and death of his grandmother in her Denver home. He allegedly confessed to strangling his grandmother and stabbing her dog. Received 48 years. Is eligible for parole in 2020. (1998) Nathan Ybanez, then 17, is serving a life sentence without parole for beating his mother to death with a fireplace tool and strangling her in her Douglas County apartment in June 1998. (1998) Leon Gladwell, then 17, is serving a 40-year prison sentence for beating his grandmother to death with a tire iron in Boulder in January 1998. Est. parole date 2017. (1994) Jenna Smythe, then 19, is serving 30 years in prison for conspiring with two adults to stab her mother and a 15-year-old runaway to death in Smythe's Arapahoe County apartment in 1994. (No longer in DOC data base.) (1992) Jacob Ind, then 15, is serving two life sentences without possibility of parole for killing his abusive mother and stepfather in their Woodland Park home . (1988) Charles Limbrick, 15, killed his mother in Colorado Springs. Sentenced in 1999 to life for first-degree murder. (Sentence of 40 years) Received a limited commutation and is eligible for parole in December 2016, 12 years earlier than before the grant. (1987) Richard Mijares, 17, killed his mother, covered her with rocks and buried her in a secluded area. Then reported her missing. conviction for second degree murder. Released to community corrections in 2004. (1986) Herman Douglas French Jr., then 14, choked, beat, shot and stabbed his mother to death in her Broomfield apartment. He remains on probation until 2007. (1986) Larry Long Jr., then 18, stabbed his parents and a 17-year-old brother to death in their sleep in Longmont. He pleaded guilty to second degree murder and was sentenced to 48 years in prison, with no chance of parole before before 2010. (1983) Ross Michael Carlson, then 19, shot and killed his parents execution-style on a dirt road in Douglas County in 1983. His lawyers claimed he suffered from multiple-personality disorder. It took six years before the courts declared him competent to stand trial. He died of leukemia before trial. (1983) Michael Shane Wilkerson, then 14, beat and stabbed his mother in their Aurora home, then drowned her in the bathtub, in 1983. Relatives told investigators the woman ignored, belittled, neglected and humiliated her son. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to two to four years in a youth treatment facility in Denver. John Engel, 14, killed his adoptive mother and grandmother with a knife and claw hammer in 1999. He pleaded guilty to first-degree murder as an aggravated juvenile and was sentenced to seven years in the Division of Youth Corrections. He also pleaded guilty to second-degree murder as an adult and was sentenced to 32 years in adult prison. He becomes eligible for parole in 2018. His mandatory release date is 2031. Leon Gladwell, 17, of Boulder was arrested in January 1998 for beating his grandmother to death with a bicycle fork. He pleaded guilty to an adult second-degree murder charge and was sentenced to 48 years in an adult prison. He becomes eligible for parole in 2017. His mandatory release date is 2036. Appendix B Cases which occurred in El Paso County. There were 10 counties present in the study of which 40 % occurred in El Paso County making El Paso the predominant county overall. County2 Cumulative Frequency Valid Percent Valid Percent Percent El Paso 12 40.0 40.0 40.0 Other 18 60.0 60.0 100.0 Total 30 100.0 100.0 Statistics Age N Valid 30 Missing 0 Mean 15.50 Median 16.00 Mode 17 Age Cumulative Frequency Valid Percent Valid Percent Percent 10 1 3.3 3.3 3.3 13 3 10.0 10.0 13.3 14 3 10.0 10.0 23.3 15 5 16.7 16.7 40.0 16 7 23.3 23.3 63.3 17 11 36.7 36.7 100.0 Total 30 100.0 100.0 The mode has significance to this study. The majority of cases occur from those age 17 and the study has cases ranging from age 10-17. It shows there may be some relevance in searching further for attributing age into whether or not a minor is tried as an adult versus crime severity alone. Particularly with the mean age one year younger at 16 years old. Sentenceyrs3 N Valid Missing 30 0 Mean .43 Median .00 Mode 0 Sentenceyrs3 Cumulative Frequency Valid Percent Valid Percent Percent 40 years or less 17 56.7 56.7 56.7 over 40 years 13 43.3 43.3 100.0 Total 30 100.0 100.0 Appendix C Chi-Square Tests Value Pearson Chi-Square Continuity Correctionb Likelihood Ratio Asymp. Sig. (2- Exact Sig. (2- Exact Sig. (1- sided) sided) sided) df 4.751a 1 .029 2.999 1 .083 4.651 1 .031 Fisher's Exact Test .068 Linear-by-Linear Association N of Valid Cases 4.593 1 .032 30 a. 2 cells (50.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 2.57. b. Computed only for a 2x2 table Lambda Symmetric TriedAs Dependent Age2 Dependent TriedAs Dependent Age2 Dependent .167 .273 .000 .158 .158 .126 .205 .000 .136 .139 1.159 .246 1.159 .246 .c .c .032d .032d .043 Appendix D Sentenceyrs3 * Age3 Crosstabulation Count Age3 age 10-15 Sentenceyrs3 40 years or less Total 10 7 17 2 11 13 12 18 30 over 40 years Total 16 and 17 Case Processing Summary Cases Valid N Sentenceyrs3 * Age3 Missing Percent 30 N 100.0% Total Percent 0 .0% N Percent 30 100.0% Chi-Square Tests Value Pearson Chi-Square Continuity Correctionb Likelihood Ratio df Asymp. Sig. (2- Exact Sig. (2- Exact Sig. (1- sided) sided) sided) 5.792a 1 .016 4.123 1 .042 6.183 1 .013 Fisher's Exact Test Linear-by-Linear Association N of Valid Cases .026 5.599 1 .018 30 a. 0 cells (.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 5.20. b. Computed only for a 2x2 table .019 Symmetric Measures Asymp. Std. Errora Value Ordinal by Ordinal Gamma .774 N of Valid Cases Approx. Tb .183 Approx. Sig. 2.763 .006 30 a. Not assuming the null hypothesis. b. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. Appendix E Sentenceyrs3 * Timeline2 Crosstabulation Timeline2 before 93 and 1993-2001 Sentenceyrs3 40 years or less Count 12 17 35.7% 75.0% 56.7% 9 4 13 64.3% 25.0% 43.3% 14 16 30 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% Count % within Timeline2 Total Count % within Timeline2 Total 5 % within Timeline2 over 40 years after 2001 Symmetric Measures Asymp. Std. Errora Value Ordinal by Ordinal Gamma N of Valid Cases -.688 30 a. Not assuming the null hypothesis. b. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. Approx. Tb .212 -2.339 Approx. Sig. .019 Correlations Timeline2 Timeline2 Pearson Correlation Sentenceyrs3 -.396* 1 Sig. (2-tailed) .031 N Sentenceyrs3 Pearson Correlation 30 30 -.396* 1 Sig. (2-tailed) .031 N 30 30 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). Variables Entered/Removedb Model 1 Variables Variables Entered Removed Timeline2a Method . Enter a. All requested variables entered. b. Dependent Variable: Sentenceyrs3 Model Summary Model 1 R .396a R Square .156 a. Predictors: (Constant), Timeline2 Adjusted R Std. Error of the Square Estimate .126 .471 Works Cited Kurleychek, M. C., & Johnson, B. D. (2010). Juvenility and Punishment: Sentencing Juveniles in Adult Criminal Court. Criminology, 725-749. Kurlychek, M. C., & Johnson, B. D. (2004). The Juvenile Penalty: A Comparison of Juvenile and Young Adult Sentencing Outcomes in Criminal Court. Criminology, 485-508. Myers, D. L. (2003). Adult Crime, Adult Time: Punishing Violent Youth in the Adult Criminal Justice System. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 173-192. Urbina, M. G., & White, W. S. (2009). Waiving Juveniles to Criminal Court: Court Officials Express Their Thoughts. Social Justice, 122-136.