Lecture 7: The Commerce Clause And Other Power

advertisement

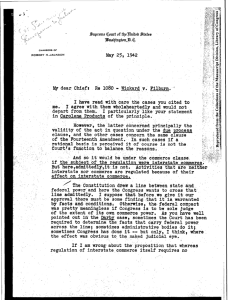

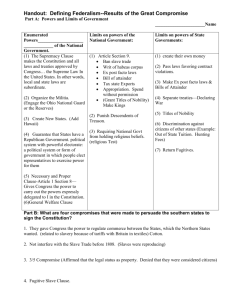

Lecture 8: The Commerce Clause And Other Power-Expanding Mechanisms Inherent in the notion of government is the power to regulate human conduct. Under the compact theory of government, the people themselves determine the limits and extents of their government’s authority to so regulate. In our federal form of government, a key constitutional question is which level of government has the authority to regulate a given sphere of activity – the central government or the states? Chief Justice John Marshall observed: “In our complex system, presenting the rare and difficult scheme of one general government, whose action extends over the whole, but which possesses only certain enumerated powers, and of numerous state governments, which retain and exercise all powers not delegated to the Union, contests respecting power must arise.”1 In the last lecture, we discussed how the U. S. Supreme Court assumed greatly-expanded powers to control the states through its “interpretation” of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause. It is probably universally conceded that the prime function of the judiciary is to interpret and apply the law to the facts and controversies brought before it. But at some point it becomes ridiculous to say that they are merely “interpreting” the Constitution when in fact, they are changing or amending it by judicial fiat. They did that regarding the 14th Amendment and they also did it concerning the commerce clause of Article 1, Section 8 which is the main focus of this lecture. The Court’s interpretations of the powers delegated to the federal government under the commerce clause are a classic example of the “slippery slope” analogy. Imagine yourself on the crest of a slick and steep rock formation. If you were to take one step forward, your fate would be sealed because you couldn’t stop until you slid, tumbled, or rolled all the way to the bottom – there could be no intermediate stopping point – either you are at the top or you are on your way to the bottom with no long term options in between. In my analogy, the starting point at the top of the hill represents our original situation where the states had a lot of authority to determine what went on within their respective state borders. The ending point at the bottom of the hill represents our current state of affairs where the states have very little authority to determine what goes on within their borders and the federal government controls virtually every aspect of regulatory power. Review From Past Lectures In the first lecture we discussed the various barriers to interstate and international commerce that were created by the various states to secure for themselves special advantages at the expense of the other states. The national government under the Articles of Confederation was powerless to control these things. The resulting problems were so extreme that John Marshall observed: “The power over commerce...was one of the primary objects for which the people of America adopted their government, and must have been contemplated in forming it.”2 It is very clear – based upon their recent experience with excessive centralized authority in King 1 Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824). 2 Id. 1 George and Parliament, the strength of the Anti-federalist sentiment, and the refutations of those sentiments in the Federalist Papers – that people were afraid of making too strong of a central government here in America. They wanted to give it enough power to perform its legitimate national functions but otherwise, wanted to hem it in very tightly to preserve the local control the people earned through the Revolution and loved very deeply. Remember the common theme of the anti-federalists when they argued against adoption? Their common argument was that we were on the verge of making too powerful a central government that would eventually gobble up states’ rights. Every part of the proposed constitution that could possibly be used to transform the federal government into an unlimited political authority was strenuously attacked by the anti-federalists. Hamilton, Madison, and Jay responded to those concerns in the Federalist Papers. When Madison considered the commerce clause in Federalist #45, he said: “The regulation of Commerce it is true, is a new power, but that seems to be an addition which few oppose and from which no apprehensions are entertained.” In short, nobody saw that as a potential avenue for rabid federal expansion of power, so Madison ignored it and went on to discuss other matters. Little did the Anti-federalists suspect that the commerce clause would latter serve as the springboard to unlimited federal authority. Gibbons v. Ogden In the 1824 case of Gibbons v. Ogden,3 Ogden had been given a monopoly by the State of New York to run steamboats between New York and New Jersey. Gibbons had been given a license to run steamboats between those two states by the federal Congress. The question in the case was whether Congress had constitutionally delegated authority to issue such a license under the commerce clause. The Court held that it did. In defining “commerce” the Court said: “Commerce, undoubtedly, is traffic, but it is something more; it is intercourse. It describes the commercial intercourse between nations, and parts of nations.... *** “It is not intended to say that these words comprehend that commerce which is completely internal, which is carried on between man and man in a state, or between different parts of the same state, and which does not extend to or affect other states.... “Comprehensive as the word ‘among’ is, it may very properly be restricted to that commerce which concerns more states than one. The phrase is not one which would probably have been selected to indicate the completely interior traffic of a state, because it is not an apt phrase for that purpose; and the enumeration of the particular classes of commerce to which the power was to be extended [i.e. commerce in one state involving another state, an Indian tribe, or a foreign nation], would not have been made had the intention been to extend the power to every description [of commerce.] The enumeration presupposes something not enumerated; and that something, if we regard the language or the subject of the sentence, must be the exclusively internal commerce of a state....The completely internal commerce of a state, then, may be considered as reserved for the state 3 Id. 2 itself.”4 So the Court recognized that Congress did not have the authority to regulate all types of commerce – otherwise, the Constitution would have used no modifiers to describe the word “commerce.” There is no question that Congress had the authority to regulate commerce on the waters between New York and New Jersey, for problems of that sort exactly matched the problems experienced under the Articles of Confederation and were sought to be remedied by the commerce clause. In commenting on the state inspection powers, the Court explained why those were not powers held by the federal government. It said: “[T]he [state] inspection laws are said to be regulations of commerce, and are certainly recognized in the constitution, as being passed in the exercise of a power remaining with the states. “That inspection laws may have a remote and considerable influence on commerce, will not be denied; but that a power to regulate commerce is the source from which the right to pass them is derived, cannot be admitted. The object of inspection laws, is to improve the quality of articles produced by the labour of a country; to fit them for exportation; or, it may be, for domestic use. They act upon the subject before it becomes an article of foreign commerce, or of commerce among the States, and prepare it for that purpose. They form a portion of that immense mass of legislation, which embraces every thing within the territory of a State, not surrendered to the general government: all which can be most advantageously exercised by the States themselves. Inspection laws, quarantine laws, health laws of every description, as well as laws for regulating the internal commerce of a State, and those which respect turnpike roads, ferries, &c., are component parts of this mass. (emphasis added) “No direct general power over these objects is granted to Congress; and, consequently, they remain subject to State legislation. If the legislative power of the Union can reach them, it must be for national purposes; it must be where the power is expressly given for a special purpose, or is clearly incidental to some power which is expressly given.”5 In the last chapter we introduced the idea of “police powers” – the reserved, open-ended power of the states to regulate public “safety, health, morals, and general welfare.”6 The federal government was not given such open-ended police powers. Rather it was confined to its limited delegated powers and the Court here was recognizing that fact. But whatever happened to that “immense mass of legislation, which embraces every thing within the territory of a State, [which was] not surrendered to the general government?” As we will soon see, the Supreme Court will later acquiesce to Congress’ usurpation of those open-ended powers “interpreting” the commerce clause contrary to what the framers and adopters originally intended. 4 Id. 5 Id. 6 Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905). 3 Notice too my emphasis of the word “before” in the foregoing quotation. The Court recognized that just because something was ultimately destined to be transported across state lines was not enough, in and of itself, to bring it within Congress’ regulatory authority under the commerce clause. This concept naturally led later Courts to make a distinction between production/manufacturing processes (which were deemed to be local in nature and thus outside the scope of Congress’ regulatory authority under the commerce clause), and the interstate transportation/commerce of the resulting products (which is within Congress’ authority.)7 Hammer v. Dagenhart In Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), the Court said: “Over interstate transportation, or its incidents, the regulatory power of Congress is ample, but the production of articles, intended for interstate commerce, is a matter of local regulation. * * * If it were otherwise, all manufacture intended for interstate shipment would be brought under federal control to the practical exclusion of the authority of the states, a result certainly not contemplated by the framers of the Constitution when they vested in Congress the authority to regulate commerce among the States.”8 (emphasis added) That case had to do with the Federal Child Labor Act of 1916 which totally barred from shipment in interstate commerce, products from factories which employed child labor. It is very interesting what Congress was trying to do there. Consistent with the idea that the federal government was only delegated limited authority, apparently Congress anticipated the Supreme Court would not allow it to pass a direct law in the nature of general police powers. So it tried to accomplish the same thing indirectly by stopping all interstate commerce of goods produced under circumstances they deemed to be unjust. Consistent with what courts do so often today, the Court exalted substance over mere form and held the Act to be unconstitutional. Said the court: “A statute must be judged by its natural and reasonable effect.* * * The control by Congress over interstate commerce cannot authorize the exercise of authority not entrusted to it by the Constitution.* * * “...The purposes intended must be attained consistently with constitutional limitations and not by an invasion of the powers of the states. This court has no more important function than that which devolves upon it the obligation to preserve inviolate the constitutional limitations upon the exercise of authority federal and state to the end that each may continue to discharge, harmoniously with the other, the duties entrusted to it by the Constitution. “...Thus the act in a two-fold sense is repugnant to the Constitution. It not only transcends the authority delegated to Congress over commerce but also exerts a power as 7 Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251 (1918). 8 Id. 4 to a purely local matter to which the federal authority does not extend. The far reaching result of upholding the act cannot be more plainly indicated than by pointing out that if Congress can thus regulate matters entrusted to local authority by prohibition of the movement of commodities in interstate commerce, all freedom of commerce will be at an end, and the power of the states over local matters may be eliminated, and thus our system of government be practically destroyed.”9 This however was a very close case – just a five to four majority opinion. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the four-person dissenting opinion. While he admitted that Congress could not directly regulate child labor, he thought it could do so indirectly in the way Congress tried. In other words, he would exalt form over substance in favor of expanding federal authority in the nature of general police powers so long as Congress performed just the right fancy footwork. Said he: “[Congress] may carry out its views of public policy whatever indirect effect they may have upon the activities of the States.”10 But what would be the logical extension of that proposition? What if Congress passed a law banning all interstate and international commerce with a particular state until it passed a state constitutional amendment disbanding the entire state government and transferring all of its prior powers over to the national Congress? Is there any question how the framers would have viewed such a proposed application of the commerce clause? The majority opinion best comports with the original intents of the framers. There were prior cases where the Court held federal regulation to be constitutional under the commerce clause when it came to interstate lotteries11, the Pure Food and Drug Act12 banning the interstate transportation of impure foods and drugs, and the White Slave Traffic Act13 banning the interstate transportation of women for the purpose of prostitution. The majority distinguished these cases by saying: “In each of these instances the use of interstate transportation was necessary to the accomplishment of harmful results.” In other words, the goods made with child labor did not cause any harm in the states into which they were transported in contrast with the foregoing examples. Whatever harm occurred, happened solely within the state of manufacture making it a state, rather than a federal, regulatory issue and the majority refused to allow the federal government to take indirect regulatory control over such matters through the commerce clause. Despite the strong dissenting opinion in Hammer v Dagenhart, the majority rule held for almost 9 Id. 10 Id. dissenting opinion. 11 Champion v. Ames, 188 U. . 321 (1903). 12 Hipolite Egg Co. v. U. S., 220 U.S. 45 (1911). 13 Hoke v. U. S., 227 U.S. 308 (1913). 5 twenty more years. The Court continued making distinctions between direct and indirect effects on interstate commerce and between production (considered local in nature and outside the federal commerce authority) and interstate commerce (considered national in nature thus falling within federal authority.) What changed things radically was the advent of the Great Depression. The Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal Hamilton observed: "Nothing is more common than for a free people, in times of heat and violence, to gratify momentary passions, by letting into the government, principles and precedents which afterwards prove fatal to themselves."14 The Great Depression was such a time. There was massive unemployment, an economy stuck in reverse, bank closings, foreclosures, etc. There was great suffering among the people. They cried out to be saved and Franklin D. Roosevelt said that he could deliver them through the power of the federal government. Once elected President, he recommended a lot of federal legislation to respond to the crisis and Congress, by and large, complied. The only problem, from his perspective, was that the Supreme Court found constitutional problems with that legislation. Consistent with the Hammer v. Dagenhart rationale, in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. U.S.15(1935), the Court held as unconstitutional the National Industrial Recovery Act seeking to establish codes of fair competition covering wages, hours, employment practices, working conditions, and methods of competition. In the 1936 case of Carter v. Carter Coal Co.16, the Court likewise struck down the Bitumenous Coal Conservation Act which sought to stabilize the coal industry through regulations on prices, methods of competition, and labor relations; etc. In that case, the Court emphasized that we must remember “fundamental principles....The ruling and firmly established principle is that the powers which the general government may exercise are only those specifically enumerated in the Constitution, and such implied powers as are necessary and proper to carry into effect the enumerated powers.”17 The General Welfare Clause Concerning the General Welfare clause of Article 1, Section 8, the Carter Court went on to say: “Thus, it may be said that to a constitutional end many ways are open; but to an end not 14 Alexander Hamilton and the Founding of the Nation, p.462. 15 Schechter Poultry Corp. v. U. S., 295 U. S. 495 (1935). 16 Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U. S. 238 (1936). 17 Id. 6 within the terms of the Constitution, all ways are closed. “The proposition, often advanced as often discredited, that the power of the federal government inherently extends to purposes affecting the Nation as a whole with which the states severally cannot deal or cannot adequately deal, and the related notion that Congress, entirely apart from those powers delegated by the Constitution, may enact laws to promote the general welfare, have never been accepted but always definitely rejected by this court. * * * In the Framers Convention, the proposal to confer a general power akin to that just discussed was included in Mr. Randolph’s resolutions, the sixth of which, among other things, declared that the National Legislature ought to enjoy the legislative rights vested in Congress by the Confederation, and ‘moreover to legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual Legislation.’ The convention, however, declined to confer upon Congress power in such general terms; instead of which it carefully limited the powers which it thought wise to entrust to Congress by specifying them, thereby denying all others not granted expressly or by necessary implication. It made no grant of authority to Congress to legislate substantively for the general welfare * * * and no such authority exists, save as the general welfare may be promoted by the exercise of powers which are granted.”18 So, as it should have, the Court refused to give the General Welfare clause a broad and openended meaning regarding Congress’ direct regulatory authority and it restricted the Commerce Clause to past limited interpretations. The Taxing And Spending Powers Congress tried another approach. In addition to trying to regulate and control the economy directly through the Commerce Clause, it tried to regulate and control the economy indirectly through the Taxing and Spending power. In the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, it sought to shore up the price of farm produce by encouraging farmers not to grow as much as they used to. To do this it provided cash subsidies to farmers to take land out of cultivation for certain crops. To provide the resources necessary to pay those subsidies, Congress taxed the processors of farm commodities. Congress sought to justify its actions under both the Commerce Clause and the Taxing and Spending Power under the General Welfare Clause. The 1936 test case was U. S. v. Butler.19 The Commerce Clause argument was rejected for the reasons stated above (i.e. Congress was trying to indirectly regulate local activities.) However, the court did something novel and strange regarding the second argument. It said that the Taxing and Spending Power was not limited to the exercise of the specific delegated powers listed in Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution. It held that the Taxing and Spending Powers could be used in an unlimited fashion 18 Id. 19 U. S. v. Butler, 297 U. S. 1 (1936). 7 to promote some broader notion of the General Welfare of the country. Recall from the prior lectures that Jefferson, Madison, and Story said that the General Welfare Clause was not intended to be an open-ended delegation of authority to the federal government, but rather, it was limited to the specific powers listed in Article 1, Section 8. Recall too that Madison argued in Federalist #41 that the Taxing and Spending powers were likewise limited to those same specified powers lest those specific delineations of authority become meaningless as effective limitations on federal government actions and it become a government of unlimited regulatory authority—a proposition which certainly would have been soundly rejected by the founding generation. In 1824 the U.S. Supreme Court said: “Congress is not empowered to tax for…purposes which are within the exclusive province of the states.”20 In other words, it cannot tax and spend even for things it thinks are for the general welfare of the country if those things were reserved to the states. It a can only tax and spend for things falling within its specifically delegated powers. Well, all of these notions of limitation were repudiated by the Supreme Court long before most of us were even born so we have no innate sense of impropriety about those repudiations. With Butler’s power-expanding conclusion that there were no limits on the federal government’s Taxing and Spending Powers, one would expect that the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act would be held to be constitutional but it wasn’t. Why? Because the Court said: “A tax, in the general understanding of the term, and as used in the Constitution, signifies an exaction for the support of the government. The word has never been thought to connote the expropriation of money from one group for the benefit of another.”21 But wait a minute--consistent with prior discussions about the Federalist Papers, once the Court determined that the federal government has the delegated authority to act in a certain sphere, then the Congress is the branch that is supposed to exercise will regarding how best to use that authority. The judiciary is not supposed to second-guess them and trump that legislative will. Only when the legislature tries to exercise its will outside of its delegated authority, is the judiciary supposed to step in and declare legislative actions unconstitutional. Once it ruled contrary to both of the original philosophies concerning the General Welfare clause and the Taxing and Spending Powers, then it should have been Congress’ call as to how to use those powers with the judiciary having no say in the matter. In this regard, the Supreme Court in Gibbons v. Ogden said: “...the sovereignty of Congress, though limited to specified objects, is plenary as to those objects....The wisdom and the discretion of Congress, their identity with the people, and 20 Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824). 21 Id. 8 the influence which their constituents possess at election, are...the sole restraints on which they have relied, to secure them from its abuse.”22 In other words, the only control over what Congress does within the scope of its delegated authority is political in nature and occurs at the ballot box and is not controlled by the Court. The Court knew that federal powers were supposed to be limited, but was not quite sure how to accomplish that task after interpreting the General Welfare clause and Taxing and Spending Powers so liberally in favor of federal government power. To use a common expression, once they let the genie out of the bottle, they couldn’t quite figure out how to stuff him back inside. The Butler Court’s feeble attempt to limit the federal government by taking a narrow definition of the word “tax” would not hold for very long since they effectively said that the “sky is the limit” regarding what the federal government can do under the General Welfare clause. It is the general nature of things that when you start out with a limited federal government and the U.S. Supreme Court allows one usurpation of authority by the Congress, it opens the door for the next usurpation, and the next, etc., until, as Jefferson predicted would happen, you eventually end up with a federal government that is all powerful, the 10th Amendment rendered virtually meaningless, federalism destroyed, and the states stripped of their most significant regulatory powers. While the 1936 Butler case didn’t immediately allow the federal government to rob Peter (i.e. the food processors) to pay Paul (i.e. the farmers), because of their narrow definition of the word “tax,” that limitation would later be relaxed when, pursuant to the “spirit” of the General Welfare clause, the federal government created the welfare state where it regularly robs Peter (i.e. the taxpayers) to pay Paul (i.e. welfare recipients who have to do nothing in exchange for their welfare checks or debit cards.) Regarding the Court’s interpretation of the Commerce Clause in Butler, I would not characterize what it did as judicial activism since it seems consistent with how the framers and adopters viewed the Constitution. But what it did regarding the General Welfare Clause and the Taxing and Spending Power, I would characterize as judicial activism. In a similar fashion to the Butler case, the Affordable Care Act, known by some as Obama-care, was held to be constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court under the General Welfare Clause and the Taxing and Spending Power—and not under the Commerce Clause.23 Another means whereby the Supreme Court sought to limit legislative acts at both the state and federal levels was the creation of what later became known as “substantive due process” discussed in the last lecture. Originally, the notion of due process simply focused on the inherent fairness of judicial proceedings. But somewhere along the way, the Supreme Court started interpreting the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment as allowing it to pass on the inherent fairness or wisdom of legislative processes. This too, I would characterize as judicial activism, 22 Id. 23 National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. ___ (2012). 9 for the Supreme Court reserving to itself the power to inject its own will into the legislative processes, contradicts the intents of the framers. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Response If you haven’t already done so, you should listen to Lecture 7 on FDR’s Fireside Chat from March 9, 1937. He proposed to increase the number of Justices on the U.S. Supreme Court from 9 to 15 in hopes of packing the court with liberal judges who would take a very liberal interpretation of the Constitution regarding the delegated authority to the federal government. Even though he lost that battle, he eventually won that war by having 8 appointments to the Court over his 3+ terms as President. What Did FDR’s Reconstituted Court Do With The Commerce Clause? Through a series of cases starting in 193724, the reconstituted Court started chipping away at the former judicial distinctions between direct & indirect effects on interstate commerce, and distinctions between local production & interstate commerce. In a dying gasp from the remnants of the former majority block (now turned powerless minority block,) they protested: “The Constitution still recognizes the existence of states with indestructible powers; the Tenth Amendment was supposed to put them beyond controversy.”25 Finally in the 1942 case of Wickard v. Filburn,26 all attempts by the Court to limit Congress’ authority under the commerce clause, came to a screeching halt. Farmers were struggling during the depression because their cost of production exceeded the price at which they could sell their crops. In order to save them, FDR and the Democrats passed another Agricultural Adjustment Act which addressed, from the supply side, the basic economic function of supply and demand. It boldly regulated directly rather than indirectly through taxation and subsidy as was tried under the first Agricultural Adjustment Act. It prohibited farmers from growing more than a certain amount of grain in hopes of raising the overall price of grain around the country. Filburn grew about eleven acres too much of a restricted grain and was fined for violating the Act. He defended claiming that Congress had no delegated power to pass such a law. Despite the prior case precedents holding that agriculture was a local activity belonging solely within the regulatory power of the states, this time the Supreme Court disagreed saying that Congress had the power under the Commerce Clause. 24 National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1 (1937); United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100 (1941). 25 National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1 (1937), dissenting opinion. 26 Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. 111 (1942). 10 Filburn next argued that even if the Commerce Clause potentially applied, there was no sufficient interstate commerce connection since he grew the crop primarily for personal consumption -- i.e. a merely local activity. The Court responded that even if he consumed it all personally, if he had a need for it and didn’t produce it himself, he would have had to buy it and whatever grain he would have bought might have come from another state. This, the court said, supplied a sufficient interstate commerce connection. Finally, Filburn argued that he was just a drop in the bucket. After all, what is a measly eleven acres worth of grain to a huge country like America? The court threw out this de minimis argument by basically saying, yes, you might be just a drop in the bucket but if every farmer acted like you the bucket would soon be full. One has to wonder what the federal government could not choose to regulate under that openended interpretation of the commerce clause? For example, consider the following. What if the farmers of America went to Congress and said they were losing money since people grew too many vegetables in their backyard gardens and consequently weren’t buying as many vegetables from the farmers causing prices to be low for farm produce and the farmers to be losing money? If in response, Congress passed a Bill outlawing the growing of backyard gardens, could Wickard v. Filburn be cited as valid U.S. Supreme Court authority justifying the constitutionality of that Bill under the Commerce Clause? Why not?—wouldn’t the backyard gardeners be making the same arguments Filburn unsuccessfully made? Forget the distant notion that the federal government has only limited delegated powers – now it basically has them all. And how again did this all come about? – by the democratic amendment process? No – by judicial activism making the Constitution into “a living document” as some have called it under the guise of “interpretation.” And what do many people expect the Supreme Court to do shortly through the same illegitimate process? – Force gay marriage onto all of America. It came very close to doing just that in July of 2013 when it (1) declared the Federal Defense of Marriage Act to be unconstitutional27 and (2) let stand the lower federal courts’ rulings that California’s state constitutional provision defining marriage as only being between one man and one woman, was unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses.28 It refused to hear that case since neither the Governor nor the state Attorney General were willing to defend their state constitution in federal court and the Supreme Court said that the promoters of Proposition 8 therefore had no standing to defend it in federal court. I fully expect that when some other state’s Governor or Attorney General is willing to go to federal court to defend a similar state constitutional provision, the U.S. Supreme Court will probably explicitly rule as the lower federal courts did in the Perry case. Anyway, to return to my original analogy, interpreting the Commerce Clause turned into a slippery slope for the Court. While part of the way, the Court tried to limit federal powers under it, bowing to political pressures it eventually threw up its hands and let the slide continue all the 27 28 United States v. Windsor, 507 U.S. ___ (2013). Hollingsworth v. Perry, 507 U.S. ___ (2013). 11 way to the bottom resulting in a very powerful federal government and very weak states. In the 6th lecture, I discussed a case where four judges argued in a dissenting opinion that the 14th Amendment incorporates the Bill of Rights and applies those handcuffs against the states in addition to the federal government. Where did those four judges come from after almost eighty years of judicial experience with the 14th Amendment and with only two out of thirty-three prior judges making the same argument? Those four judges were all FDR appointments. In later years, the Warren Court (led by Chief Justice Earl Warren) would further accelerate judicial activism in favor of expanding the role of the Supreme Court and Congress. The New Deal judicial activism sacrificed property rights for what FDR called “social and economic progress” and which today would be called “social justice.” Earlier I called this the “sociological school of jurisprudence” championed by Roscoe Pound of Harvard. The Warren Court’s judicial activism tended to nationalize moral issues by prohibiting prayer in school, the placing of Christmas decorations in the public square, the regulation of pornography, etc. This judicial activism has happened so often and over such a long period of time that people naturally assume – incorrectly – that it is all constitutionally legitimate. The Need To Retrace Our Steps After The Crisis Passed Along with Hamilton, Jefferson too foresaw the probability for dangerous changes to our political structure in times of national crisis like the Great Depression. In his first inaugural address, after summarizing what he called “the creed of our political faith” or “the essential principles of our government,” he warned: “and should we wander from them in moments of error or alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety.”29 Unfortunately, once the economic storm passed, we did not return to the basic principle of a federal government with only limited delegated authority – it can do virtually whatever it wants by way of regulation. Although many would say that the justices were only doing their job by interpreting the Constitution, this is little more than verbal subterfuge – in reality they were changing it quite radically. And when we allow that to be done, we are basically admitting that we really have no Constitution in any meaningful sense. Recalling Jefferson’s words: "Our peculiar security is in possession of a written Constitution. Let us not make it a blank paper by construction [interpretation]."30 Lest you too are inclined to take an “ends justifies the means” approach and conclude that what the Court did in Wickard v. Filburn had to be done in order to save us from the Great Depression, consider the fact that several economists31, like Nobel prize-winner Milton 29 30 31 First Inaugural Address, 3/4/1801; Works 8:4-5. Letter to William Cory Nicholas, September 7, 1803, reproduced at “www.constitution.org/tj/jeff10.txt”, p.419. See FDR’s Folly–How Roosevelt and His New Deal Prolonged the Great Depression by Jim Powell. 12 Friedman, argue that the interventions into the free market made by the federal government during the Great Depression actually made things worse economically, and artificially extended its length. People should realize that one of the most important issues they face as voters in considering who they want for President, is what type of federal judges he or she will nominate to the bench. Other Ways The Federal Government Has Gotten Stronger At The Expense Of The States The 16th Amendment The 16th Amendment (1913) allowed the federal government to tax "incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration." Before this time, when it came to direct taxes on people, Congress was limited to doing so on a per capita or head count basis. It couldn't distinguish between rich people and poor people. The tax was based upon the census data of the numbers of people in the respective states. The passage of the 16th Amendment represents an interesting case study about political promises made (and later broken) in order to get a particular law passed. If the text of the law does not itself contain those promises of limitation, then such promises are inherently unreliable and mean nothing. Concerning the 16th Amendment, Charles Adams tells us: “There was an assurance by the proponents that the rates would never be high–that rates would never reach double digits. The first income tax law had a 7 percent maximum, which was changed to 15 percent in 1916 [which was just three years after passage]. In 1917 it jumped to 67 percent, then 77 percent [in 1918].”32 (emphasis added) This extremely quick escalation in the federal tax rates also illustrates the slippery slope idea. Once Congress got a taste for taxing for “social progress,” it developed what seemed to be an almost unquenchable appetite. From 1944-45, the highest marginal tax rate jumped all the way to 94%! “Oh, did we say double digits? We’re sorry--we mis-spoke. What we really meant to say was ‘triple digits.’ We are so sorry about the misunderstanding.” Without any effective limitation on the taxing and spending powers as argued by Madison in Federalist #41, and with the rules of tax imposition changed by the 16th Amendment, Congress could quickly generate a pool of funds that could be dangled in front of the noses of the states in order to get them to do the federal bidding. This is called "strings money." If the states want the money – which they almost always do – they have to jump through the federally mandated hoops and thus, effectively, the federal government calls the shots. This was the mechanism used by the federal government to force the states to lower their speed limits to 55 mph through the 1980's and most of the 1990's. By the way, as an interesting side note that I discovered in my research, I always wondered why the Constitution prohibited Congress from imposing export taxes. This was done to appease the 32 Charles Adams, For Good and Evil: The Impact of Taxes on the Course of Civilization, p.380. 13 southerners in the Constitutional Convention who worried that Congress might try to indirectly destroy slavery through imposing taxes on the exports of produce and goods produced by slaves. They worried that they might be taxed out of business.33 As it turns out, such an anticipation was probably very insightful and reasonable on their parts for the Supreme Court later observed: “It was said by Chief Justice Marshall, in the case of McCulloch v. The State of Maryland, that the power to tax is the power to destroy. A striking instance of the truth of the proposition is seen in the fact that the existing tax of ten per cent imposed by the United States on the circulation of all other banks than the National banks, drove out of existence every State bank of circulation within a year or two after its passage. This power can as readily be employed against one class of individuals and in favor of another, so as to ruin the one class and give unlimited wealth and prosperity to the other, if there is no implied limitation of the uses for which the power may be exercised. To lay with one hand the power of the government on the property of the citizen, and with the other to bestow it upon favored individuals to aid private enterprises and build up private fortunes, is none the less a robbery because it is done under the forms of law and is called taxation.”34 The foregoing destruction of the state banks through taxation was purposeful and not inadvertent.35 I had heard many times the phrase about the destructive power of taxation, but I never realized that we actually have some history where it was not just a theoretical possibility, but actually happened. The 17th Amendment The 17th Amendment changed the way Senators were elected. Professor Erik McKinley Erikkson observed: “The senators, said the Federalists, were to be ambassadors of the states and so should have some permanency of tenure. They should not be brought directly under popular control as that would, it was asserted, obliterate the states and lead to the consolidation which the opponents of the Constitution professed to fear.”36 So originally Senators were elected by the various state legislatures and not by the popular vote of the people. Thus, their constituencies were the states themselves -- that is who they represented. If the House of Representatives and the President wanted to do things that would impinge upon states' rights, the Senators in the Senate could stop any such attempt in order to protect their political constituents – the states. Even though I disagree with this change, I cannot complain that it came about improperly since it 33 American Constitutional History, Erik McKinley Erikson, published by W.W. Norton & Co, 1933, p. 203. 34 Loan Association v. Topeka, 87 U. S. 655 (1874); that the destruction was purposeful is indicated in the dissenting opinion by Justice Holmes in Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U. S. 251 (1918). 35 Id. 36 American Constitutional History, Erik McKinley Erikson, published by W.W. Norton & Co, 1933, p. 230. 14 occurred through the proper mechanism – a Constitutional Amendment. Creating Rights Out Of Thin Air In the last lecture I talked about the “selective incorporation doctrine” applying most of the things in the Bill of Rights against the states. It is one thing to incorporate things that actually appear in the Bill of Rights, it is completely another to create new “rights” out of the thin air of “substantive due process” and apply them against the states. The prime example of this was Roe v. Wade37 where the Supreme Court outlawed state laws regulating abortion under a newly created right to privacy which is nowhere to be found in the Bill of Rights. It did the same thing in establishing a right to homosexual conduct in Lawrence v. Texas38 out of the Court’s secular musings about the “meaning of life” and the “mysteries of the universe.” One can only wonder how far the Supreme Court can go when it decides to depart from the constitutional text, and from our American history and traditions. Conclusion As one can see from this and the prior materials, our Constitution has been changed quite radically under the guise of “interpretation.” Very few people understand this history and consequently, perceive nothing to be wrong. The purpose of these materials is to reacquaint Americans with a sense of our own constitutional history in order to help us properly evaluate what plays out before our eyes in the federal courts and in presidential elections. What is so profoundly troubling, is that because of our general ignorance of these things, the vast majority of Americans fail to discern the duplicity of those, who on the one hand, argue that the Constitution is too important to tinker with through democratic amendments, and then in the next breath, praise the Supreme Court for undemocratically changing it at their whim into what is euphemistically called “a living document” through “interpretation.” That praise would only last as long as the Supreme Court were making changes of which those people approved. One can bet that as soon as the Court made disagreeable changes, their love affair with judicial activism would quickly come to an end and they would return to the fundamentals discussed in these lectures. Our educators have let us down by letting America lapse into a state of ignorance about our basic constitutional principles and history. As George Orwell warned us, propaganda is as much a matter of what is left out, as of what is actually said. Now that we have seen how FDR radically changed the philosophy of the U.S. Supreme Court by his carefully selected 8 liberal Supreme Court appointments, and how the newly constituted Court basically said that the federal government could do and regulate pretty much whatever it wants in contravention of the intents of the framers, now let’s consider with FDR did with that expanded power and what negative effect it likely had on the willingness of capitalists to take 37 Roe v. Wade, 410 U. S. 113 (1973). 38 Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U. S. 558 (2003). 15 risks with their money and invest their capital in new business ventures or expand existing ones during the Great Depression. Let’s examine FDR’s New Deal policies to regulate the economy and radically expand the welfare state in our movement as a country towards socialism, or perhaps more correctly, fascism, which, in FDR’s March 9, 1937 fireside chat, he called “the modern movement for social and economic progress.” Despite what most of you were probably taught in school about FDR being our economic savior and saving us from the Great Depression, I think you will agree with me that in all likelihood, the Great Depression became much greater than any prior depression because of the very economically discouraging regulatory and taxing policies of FDR’s New Deal. That will be the topic of the next lecture. 16