Contract Outline 9

advertisement

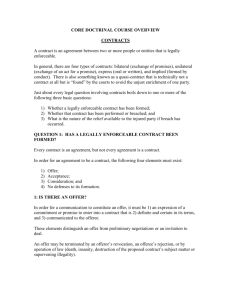

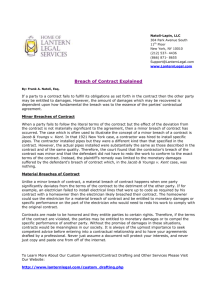

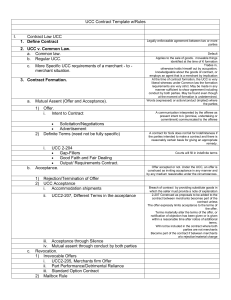

Contract – a promise for which the law gives remedy in the case of a breach I. Formation – is there a contract in the first place? A. Types of Contracts (Formation): i. Express K – formed by language; can be oral or written ii. Implied in Fact K – formed by manifestations of assent other than language (conduct) iii. Quasi-K or Implied in Law K – not Ks at all but constructed by the courts to avoid unjust enrichment a. Permits ∏ to bring an action in restitution to recover the amount of the benefit conferred on the ∆ B. Types of Contracts (Acceptance): i. Bilateral K – exchange of mutual promises a. I promise to pay you $1000 if you promise to paint my house ii. Unilateral K – acceptance by performance a. I promise to pay you $1000 if you paint my house b. Test – a unilateral K is made if at the time the contract is formed, ONLY the offeror has unperformed duties II. Offer and Acceptance A. Offer – a statement of terms that creates the power of acceptance i. Was there an expression of promise, undertaking, or commitment to enter into a contract? – must be intent to enter into a contract a. Language – technical “I offer/I Promise” terms are not necessary 1. Ambiguous language will be construed in favor of the offeree b. Surrounding Circumstances – context of the statement will be interpreted according to a reasonable person’s expectations c. Prior practice and relationship of the parties d. Method of Communication – advertisements are usually construed as invitations for offers e. Industry Custom f. Certainty and Definiteness of Terms – the more inquiries there are, the more likely it is part of preliminary negotiations ii. Were there certainty and definiteness in the essential terms? – must contain essential elements to make K capable of being enforced: a. Identification of the Offeree – actual person or class to which she belongs 1. Performance can constitute both identification and acceptance (reward) b. Definiteness of Subject Matter – doesn’t have to spell out every material term but must contain some objective standard 1. Requirements for specific types of Ks a. Real Estate Transactions – must identify land and price b. Sale of Goods – quantity must be certain or capable of being made certain (1) Requirements Contract – a buyer promises to buy from a certain seller all the goods she requires and the seller agrees to sell that amount to the buyer (2) Output Contract – seller promises to sell to a certain buyer all the goods the seller produces and the buyer agrees to buy that amount from the seller c. Employment Contracts – duration must be stated or it is considered employment at will 2. Inference of Reasonable Terms – terms not spelled out will be supplied by the court by a “reasonableness” standard including: a. Price Term – reasonable price will be supplied (2-305) unless parties have showed they don’t want a contract until price is agreed upon b. Specific Time Provision – performance within a reasonable time is implied (2-309) 3. Vague Terms – if a term is included but too vague, the contract cannot be enforced a. Ex. Agreement to purchase land for “$8000 or less” or agreement to divide profits “on a liberal basis” both too vague b. Vagueness can be cured by part performance – where part performance supplies the needed verification c. Uncertainty can be cured by Acceptance – if offeree is given choice alternatives, offer is definite when offeree communicates her choice d. Focus on Contract – offer uncertainty problems can often be cured by looking at the contract as a whole or performance 4. Terms to be Agreed on – if offer states that terms are to be decided at later date, the offer is too uncertain if the term is a material term iii. Was there communication of the above to the offeree? – offeree must have knowledge of the offer to have the power to accept iv. Termination of Offer – power of acceptance ends when offer is terminated a. Termination by Offeror – Revocation 1. Must be communicated before the offeree accepts 2. Revocation is effective when it is received 3. Offers can be revoked at will by the offeror even when he promised not to revoke it for a certain period of time 4. Limitations to revocation: a. Options – when the offeree gives consideration for a promise by the offeror not to revoke b. Firm offers under the UCC – an offer by a merchant to buy or sell goods in a signed writing that states it will be held open is not revocable for stated period of time (2-205) (1) If time is not stated, then a reasonable time no longer than 3 months c. Detrimental Reliance – where offeror could reasonably expect that offeree would rely on the offer, it’s irrevocable for a reasonable length of time (R2d 87) (1) Ex. General contractor relies on subcontractors’ offers to generate overall bid. Subcontractor must reasonably foresee use of its bid. d. Part Performance (True Unilateral Contract Offers) – offer becomes irrevocable once performance has begun (1) Once offeree begins, she is given a reasonable time to complete performance (R2d 45) (2) Part performance doesn’t include preparation to perform but substantial preparations may constitute detrimental reliance sufficient to maker offeror’s promise binding (R2d 45, 87, 90) b. Termination by Offeree 1. Rejection a. Express Rejection – statement by offeree that she does not intend to accept offer (R2d 36) b. Counteroffer as Rejection – rejects the offer but serves as a new offer on same subject matter but with new terms c. Effective when received by offeror d. Rejection of an option does not constitute termination of the offer – offeree is still free to accept unless offeror has detrimentally relied on the offeree’s rejection 2. Lapse of Time a. Must accept within specified or reasonable time b. Time period commences when offer is received by offeree c. Termination by Operation of Law 1. Death or Insanity of Parties – isn’t necessary that it is communicated to other party (R2d 48) 2. Destruction of Subject Matter – (R2d 36) 3. Supervening Legal Prohibition of Proposed Contract – if subject matter becomes illegal (R2d 36) B. Acceptance – manifestation of assent to the terms of an offer creating a contract i. Offer may only be accepted by the person to whom an offer is addressed ii. Acceptance must be unequivocal a. UCC Rule – proposal of different terms by offeree does not constitute rejection or counteroffer and acceptance is effective unless it is expressly made conditional on assent to the additional terms. b. When do additional terms become part of the contract?: 1. Party not a Merchant – Terms of offer govern a. Additional terms are considered proposals to modify the K that do not become part of K unless offeror agrees 2. Both Parties Merchants – Acceptance terms usually included a. Additional terms automatically become part of K unless: (1) They materially alter the original terms of the offer, (2) The offer expressly limits acceptance to the terms of the offer, or (3) The offeror has already objected to the particular terms or objects within a reasonable time after notice of them is received 3. Writings that do not Create a Contract – when offeror enters clause saying “no additional terms” allowed and offeree responds with new terms only agreeing if offeror consents to new terms a. No contract until performance begins, then there is K b. K consists of all terms on which the writings agree plus supplementary terms supplied by the UCC (2-207) c. Generally, Acceptance must be Communicated 1. May be accepted by any medium reasonable in the circumstances (2-206) unless unambiguously stated in the offer 2. Acceptance by unauthorized means may still be effective if it is actually received by the offeror while the offer is still in existence 3. Exception – Acceptance without Communication a. Express Waiver in Offer – (1) Ex. Mail-in order form is offer pending home office approval. Home office doesn’t have to notify offeror of acceptance b. Act as Acceptance – offer requires some act (not performance) and when offeree performs the act requested with intent of accepting, K is formed c. Silence as Acceptance – if offeree silently takes offered benefits, courts will often find acceptance (R2d 69) (1) Courts will look to prior dealings between parties or trade practices known to both which give the offeree a duty to notify the offeror if she doesn’t intend to accept III. Consideration A. Consideration – in order to be enforceable in court, a contract must have consideration (there must be a bargained-for exchange between parties which must be considered of legal value (a benefit to the promisor or a detriment to the promisee)) i. Elements of Consideration: a. Bargained-for Exchange – the promisor makes his promise in exchange for the promisee’s giving of value or circumscription of liberty 1. Gift – if either of the parties intended to make a gift, he was not bargaining for consideration and this requirement will not be met a. Act or Forbearance by Promisee must be of Benefit to Promisor (1) Ex. Come to my house and I will give you my old television – promisee suffers detriment by going to promisor’s house but the promise was probably not made to induce the promisee to come to the promisor’s house; no consideration b. Economic Benefit Not Required (1) Ex. Father tells daughter he will give her $1000 if she stops smoking – emotional gratification from daughter’s health suffices as consideration 2. Past Consideration – generally if something was already given before the promise was made, it will not satisfy the bargain requirement a. Exceptions: (1) Debt Barred by a Technical Defense – if past obligation would be enforceable except for technical defense (statute of limitations, etc.), courts will enforce new promise if it is in writing or has been partially performed (2) Promise to Pay for Past Requested Act – if acts were previously performed at the request of promisor, a new promise will be enforceable (R2d – covers unrequested acts if they were rendered during emergency) (3) Terms of New Promise Binding – most courts will apply terms of new promise b. Legal Value – exchange must constitute a benefit to the promisor or a detriment to the promisee 1. Adequacy of Consideration – courts will normally not inquire into the relative values exchanged a. Token Consideration – where consideration is only a token (devoid of value), it will usually not be legally sufficient and rather a gift b. Sham Consideration – if consideration was $1 its frequently never paid and evidence is allowed to show it was not paid and no other consideration was given c. Specific Situations 1. Pre-existing Legal Duty – generally the promise to perform and existing legal duty will not be sufficient Consideration a. Exceptions – R2d 82-90 and UCC 2-209 2. Forbearance to Sue – the promise to refrain from suing on a valid claim (or an invalid claim that the claimant in good faith believes is valid) constitutes consideration ii. Mutual and Illusory Promises – consideration must exist on both sides of the contract, i.e. promises must be mutually obligatory. If one party has become bound and the other is not, it is illusory and consideration fails. Mutuality still exists in certain situations even though the promisor has some choice: a. Requirements and Output Contracts – promisor is suffering legal detriment by promising to buy/sell all goods from promisee (UCC 2-306) 1. No Unreasonably Disproportionate Quantities – may not be disproportionate to any stated estimate or any normal or comparable prior need even if the change is made in good faith 2. Going out of Business – promise is still mutual 3. No Reasonably Established Business – UCC reads the “good faith” agreement into the contract, must operate according to commercial standards of fair dealing in the trade b. Conditional Promises – are enforceable unless the “condition” is entirely within the promisor’s control 1. Promise conditioned on satisfaction is not illusory since one cannot reject them unless dissatisfied, must use good faith (UCC 1-304) c. Right to Cancel or Withdraw – consideration is valid if the right is in any way restricted (e.g. right to cancel upon 60 days notice). 1. Reasonable notice implied by the UCC if not specified in K (UCC 2-309(3)) d. Best Efforts Implied – court may find implied promise in appropriate circumstances 1. Ex. Y has exclusive rights to sell D’s dresses in return for ½ profit. K said no obligation for Y but court implied Y promised to use best efforts to sell (UCC 2-306(2)) e. Voidable Promises – although a contract is voidable by one party, they are not held objectionable on “mutuality” grounds (R2d 78) iii. No Requirement that all Consideration be Valid – not all of the promises given as consideration necessarily must be sufficient as consideration, as long as one is, consideration is satisfied iv. Substitutes for Consideration – can make an agreement partially enforceable a. Promissory Estoppel or Detrimental Reliance 1. Majority View – consideration is not necessary where the facts indicate that the promisor should be estopped from not performing 2. Elements of Promissory Estoppel (R2d 90): a. A promise is enforceable to the extent necessary to prevent injustice if: (1) The promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance; (2) And such action or forbearance is in fact induced (3) Remedy for breach may be limited as justice requires b. Promises in Writing 1. UCC and Written Promises a. Modification of a Contract – consideration is not necessary to a good faith modification, oral or written. Only has to be written if the K as modified is within the Statute of Frauds (UCC 2-209) b. Firm Offers by Merchants – merchants may bind themselves to keep an offer open (not over 3 months) if it is in writing and signed by offeror (UCC 2-205) c. Any claim arising out of alleged breach of sales contract may be discharged without consideration by agreement of the aggrieved party in an authenticated record (UCC 1-306) c. Reaffirmation of Voidable Promise – although originally not enforceable, if an incapacitated person affirms the contract upon attaining capacity, her promise at that time will be binding IV. Defenses A. A contract will not be enforceable if there is a valid defense to formation of the contract, a defect in capacity, or a defense to enforcement of certain terms B. Defenses to Formation i. Absence of Mutual Assent a. Mutual Mistake – where both parties entering into a contract are mistaken about facts relating to the agreement, K may be voidable by the adversely affected party if: 1. The mistake concerns a basic assumption on which the contract was made; 2. The mistake has a material effect on the agreed-upon exchange; and 3. The party seeking avoidance did not assume the risk of the mistake a. Assumption of Risk – mutual mistake is not a defense if the adversely affected party bore the risk that the assumption was mistaken (common where parties knew that assumption was doubtful b. Ex. Roger finds stone and shows to Betsy. Both assume it is Topaz and he sells to her for $100. Stone is actually diamond worth $1000. Roger cannot recover because they knew assumption was doubtful c. Ex. Roger finds stone and shows to Jeweler. Jeweler in good faith tells Roger it’s Topaz and buys for $100. Roger finds out it’s a diamond worth $1000. Roger can rescind because he relied on the expert’s opinion. b. Unilateral Mistake – where only one of the parties is mistaken about facts relating to the agreement, mistake will not prevent formation of K. However, if nonmistaken party knew or had reason to know of the mistake made by the other party, he will not be permitted to snap up the offer 1. Unilateral Mistake May be Canceled in Equity – authority holds that Ks with errors (such as mistake in computation) may be canceled in equity assuming that the nonmistaken party has not relied on the contract. a. Also authority that a unilateral mistake that is so extreme that it outweighs the other party’s expectations will be ground for cancellation 2. Error in Judgment – an error in judgment as to the value or quality of work or goods will not prevent formation of a K, even if the nonmistaken party knows or has reason to know of the mistake made by the other party c. Latent Ambiguity Mistakes – Mutual Misunderstanding – the expression of the parties’ agreement appears clear at the time K is formed but because of subsequently discovered facts, the expression may be reasonably interpreted in either of two ways. Possibilities: 1. Neither Party Aware of Ambiguity – NO Contract unless both parties happened to intend the same meaning a. CASE – Raffles v. Wichelhaus – Ship to deliver cotton named Peerless but there were 2 ships with that name. Buyer expected ship in Sept. while seller meant ship in Dec. They did not intend the same ship therefore no contract 2. Both Parties Aware of Ambiguity – NO Contract unless both parties in fact intended the same meaning 3. One Party Aware of Ambiguity – Contract enforced according to the intention of the party who was unaware of the ambiguity 4. While courts normally use an objective test, these situations require the courts to look to the subjective intention of the parties d. Misrepresentation 1. Fraudulent Misrepresentation Voidable – if a party induces another to enter into a K by using fraudulent misrepresentation (e.g. asserting info she knows is untrue), the K is voidable by the innocent party if she justifiably relied on th fraudulent misrepresentation (Fraud in the Inducement) a. Fraud in the Factum – if one of the parties was tricked into giving assent to the agreement under circumstances that prevented her from appreciating the significance of her action, K is void 2. Nonfraudulent Misrepresentation Voidable if Material – even if misrepresentation was not fraudulent, K is voidable by innocent party if they justifiably relied on the misrepresentation and it was material a. A misrepresentation is material if either: (1) The information asserted would induce a reasonable person to agree, or (2) The maker of the misrepresentation knew the information asserted would cause a particular person to agree 3. Innocent party doesn’t have to wait until she is sued on the contract but can rescind the agreement. ii. Absence of Consideration – if promises at formation stage lack elements of bargain or legal detriment, no contract exists (one of the promises is always illusory) iii. Public Policy Defenses to Contract Formation – if either the consideration or the subject matter of a K is illegal, this will serve as a defense to enforcement a. Contracts may be illegal because they are: 1. Inconsistent with the Constitution, 2. Violate a Statute, or 3. Against public policy as declared by the courts b. Most Common Areas of Illegality: 1. Agreements in restraint of trade 2. Gambling contracts 3. Usurious contracts 4. Agreements obstructing administration of justice 5. Agreements inducing breach of public fiduciary duties 6. Agreements relating to torts or crimes c. Effect of Illegality 1. Generally Contract is Void 2. Effect Depends on Timing of Illegality – if subject matter or consideration: a. Was illegal at time of offer – no valid offer b. Became illegal after offer but before acceptance – revokes the offer c. Became illegal after valid K was formed – discharge of contract 3. If contract was formed for an illegal purpose, but neither consideration nor subject matter was illegal: (R2d 182) a. Contract is only voidable by the party who (1) Did not know of the purpose, or (2) Knew but did not facilitate the purpose and the purpose does not involve “serious moral turpitude” b. Contract is void and unenforceable if: (1) Both parties knew of the illegal purpose and facilitated it, or (2) Both parties knew and the purpose involves serious moral turpitude d. Limitations on Illegality Defense 1. Plaintiff Unaware of Illegality – if ∏ contracted without knowledge of illegality and ∆ knew of illegality, innocent ∏ may recover on K 2. Parties Not in Pari Delicto – a person may successfully seek relief if he was not as culpable as the other C. Defenses Based on Lack of Capacity i. Individuals who are legally incapable are protected from contractual obligations. Assertion of this defense by a promisor makes the K voidable at his election a. Contracts of Infants 1. Who is an Infant? a. Most jurisdictions say the age is 18. Some are passing legislation for contractual purposes at a younger age. In many states, married persons under 18 are considered adults 2. Effect of Infant’s Contract – a contract made between an infant and an adult is voidable by the infant but binding on the adult 3. An infant may affirm (choose to be bound) the contract upon reaching adulthood either expressly or by conduct 4. Exceptions – infant cannot choose to avoid the contract entered into by him: a. Necessities – an infant is bound to pay the reasonable value of necessities (1) These depend on the infant’s station in life b. Statutory Exceptions – some states have statutory exceptions (usually insurance, student loans, etc.) b. Mental Incapacity – one whose mental incapacity is so deficient that he is incapable of understanding the nature and significance of a contract, it is voidable 1. May affirm during a lucid interval or upon complete recovery 2. Liable in quasi-contract for necessities furnished to them c. Intoxicated Persons – one who is so intoxicated as to not understand the nature and significance of promise may have a voidable promise only if the other party had reason to know of the intoxication 1. May affirm the K upon recovery 2. Quasi-contractual recovery for necessities furnished during period of incapacity ii. Lack of Volitional Consent – although party may have the legal capacity, consent to the bargain may be ineffective a. Duress and Coercion – Ks induced by duress or coercion are voidable and may be rescinded as long as not affirmed 1. Duress will usually not be found where one party takes economic advantage of the other’s pressing need to enter into a contract b. Fraud in the Inducement – voidable at the election of the innocent party D. Defenses to Enforcement i. Defenses that involve failure of the agreement to qualify for judicial relief and may arise at the formation stage or later ii. Statute of Frauds – contracts that must be evidenced by a writing signed by the parties sought to be bound a. Agreements Covered: 1. Executor or Administrator Promises Personally to Pay Estate Debts – a promise by an executor or administrator to pay the estate’s debts out of his own funds must be in writing 2. Promises to Pay Debt of Another (Suretyship) a. Must be a collateral promise b. Main purpose must not be pecuniary interest of promisor 3. Promises in Consideration of Marriage – promises that induce marriage by offering something of value (not return promise to marry) 4. Interest in Land – includes the sale of real property or interest therein, and also other agreements pertaining to land a. Covered by the statute: (1) Leases for more than one year (2) Easements for more than one year (3) Fixtures (4) Minerals (or the like) or Structures if they are to be severed by the buyer. If they are to be severed by the seller they are not an interest in land but rather goods If subject matter is growing crops, timber to be cut, or other things attached to realty capable of severance without material harm thereto, contract for sale of goods (UCC 2-107) (5) Mortgages and most other security liens b. Items not within the statute – even though end result may be an interest in land, they still do not come within the statute (1) Ex. Contract to build a building (2) Ex. Contract to buy and sell real estate and divide the profits c. Effect of Performance on Contracts – if the seller conveys to the purchaser (i.e. fully performs), the seller can enforce the buyer’s oral promise to pay d. Seller may be able to specifically enforce a land contract if the “part performance doctrine” is applicable (1) Part Performance Doctrine – conduct (i.e. part performance) that unequivocally indicates that the parties have contracted for the sale of the land will take the contract out of the Statute of Frauds (2) Most jurisdictions require at least two to constitute sufficient part performance: Payment (in whole or part) Possession Valuable Improvements 5. Performance Not Within One Year – a promise that by its terms cannot be performed within a year a. Effective Date – the date runs from the date of agreement and not from the date of performance b. Contracts not within the statute: (1) Possibility of Completion Within One Year – even though actual performance may extend beyond the one-year period, if it is possible to complete within one year it is not within the provision (2) Right to Terminate Within Year – where the K cannot be performed within a year but allows both parties to terminate within a year, there is a split as to whether this is within the Statute of Frauds (3) Lifetime Contracts – contracts measure by a lifetime is not within the statute because it is capable of performance within a year since a person can die at any time 6. Goods Priced at $500 or More (UCC 2-201) a. Oral contracts for the sale of goods over $500 are enforceable in the following situations: (1) Specially Manufactured Goods – if goods are to be specially manufactured for the buyer and are not suitable for sale to others by the seller in his ordinary course of business AND the seller has made either a substantial beginning or commitments for their procurement before notice of repudiation is received, the oral contract may be enforced (UCC 2-201(3)(a)) (2) Written Confirmation Between Merchants – a writing in confirmation of the K that is sufficient against the sender and received by the other merchant who has reason to know of its contents satisfies the SOF against recipient unless written notice of objection to the writing’s contents is given within 10 days after the writing is received (UCC 2201(2)) (3) Admissions in Pleadings or Court – if party against whom enforcement is sought admits in pleadings, testimony, or otherwise in court that the contract for the sale was made, K is enforceable but not beyond the quantity of goods admitted (UCC 2-201(3)(b)) (4) Partial Payment or Delivery – contract is enforceable to the extent of the payment received and accepted or to the extent of goods received and accepted (UCC 2-201(3)(c)) b. Goods – all things that are movable at the time of identification to the contract of sale (tangible, movable property in general) (UCC 2-105) c. Oral Modification Clause – UCC 2-209(2) expressly makes a “no oral modification clause” enforceable. However, such a clause can be waived (UCC 2-209(4)) and if the waiver is relied on, it is irrevocable (UCC 2209(5)) b. Requirements – any writing will suffice as long as it contains every essential item of the oral or implied agreement. Statute will be satisfied if the memorandum contains: 1. The identity of the party sought to be charged, 2. Identification of the contract’s subject matter, 3. Terms and conditions of the agreement, 4. Recital of consideration (in most states), and 5. Signature of the party to be charged or of his agent c. UCC Requirements (UCC 2-201) 1. Quantity 2. Signature of party to be charged 3. A writing sufficient to indicate that a contract was formed a. A writing is not insufficient because it omits or incorrectly states a term agreed upon but the contract is not enforceable beyond the quantity of goods shown in such writing d. Effect of Noncompliance with Statute – noncompliance renders the K unenforceable at the option of the party to be charged 1. If it is not raised as a defense, it is waived e. Other Situations Where Statute Not Applicable 1. Full Performance of Contract Not Performable Within One Year – generally full performance will remove the bar of the Statute 2. Promissory Estoppel – sometimes applied where it would be inequitable to allow the SOF to defeat a meritorious claim a. Ex. When defendant falsely and intentionally tells plaintiff that the contract is not within the SOF or that a writing will subsequently be executed b. Ex. When defendant’s conduct foreseeably induces a plaintiff to change his position in reliance on an oral agreement f. Remedies if Contract is Within Statute – where a K is within the Statute but there is no writing, in almost all cases a party an sue for reasonable value of the services or part performance rendered or the restitution of any other benefit that has been conferred. 1. The rationale is that it would be unjust to permit a party to retain benefits received under the failed contract without paying for them iii. Unconscionability a. UCC 2-302 allows a court to refuse to enforce a provision or an entire contract (or to modify the contract) to avoid unconscionable terms 1. The principle behind this provision is to the prevention of oppression and unfair surprise b. Basic Test – whether in light of the general commercial background and needs of the particular parties, the clauses involved are so one-sided as to be unconscionable under the circumstances existing at the time the contract was formed c. Often applied to one-sided bargains where one party has substantially superior bargaining power and can dictate the terms of the K to the party with the inferior bargaining power d. Typical Elements of Unconscionability: 1. Inconspicuous Risk-Shifting Provisions – standardized printed form contracts often contain a material provision that seeks to shift a risk normally borne by one party to the other. Examples are: a. Confession of judgment clauses, which are illegal in most states and have been attacked on a constitutional basis b. Disclaimer of warranty provisions c. “Add-on” clauses that subject all of the property purchased from a seller to repossession if a newly purchased item is not paid for (1) These clauses are typically found in the fine print in printed form contracts (2) Courts have invalidated these provisions because they are inconspicuous or incomprehensible to the average person, even if brought to his actual attention 2. Contracts of Adhesion – “Take it or Leave it” a. Courts will deem a clause unconscionable and unenforceable if the signer is unable to procure necessary goods (e.g. automobile) without agreeing to similar provision – buyer has no choice 3. Price Unconscionability – few cases have invalidated price term when buyer is charged more than the goods were actually worth a. Courts are generally reluctant to determine fairness on pricing b. Analysis relates primarily to consumer transactions in which the buyer is unaware of the actual price he was agreeing to pay V. Rights and Duties of Nonparties to the Contract A. Third Party Beneficiaries i. Basic Situation: A enters into a valid contract with B that provides that B will render some performance to C. a. A = Promisee b. B = Promisor c. C = Third Party ii. Types of Beneficiaries (R2d 302) a. Intended Beneficiary – circumstances and contract show that the promisee intended to obtain performance for beneficiary 1. Or promisee owes debt or duty to beneficiary b. Incidental Beneficiary – derives benefit from contract but is NOT the intended beneficiary c. Rights of Beneficiaries 1. Intended beneficiary may seek specific performance if it is otherwise an appropriate remedy (R2d 307) a. Intended beneficiary may recover debt if she has an enforceable claim against promisee (R2d 310) 2. Can obtain a judgment against either promisee, promisor, or both based on their respective duties to him 3. All of promisor’s defenses against promisee are available against the beneficiary (R2d 309) 4. Incidental Beneficiary has no contract rights against promisee or promisor (R2d 315) B. Assignment of Rights and Delegation of Duties i. Basic Situation: X enters into a valid K with Y. This K does not contemplate performance to or by third party. Subsequently, one of the parties seeks to transfer her rights/duties under the K to a third party. ii. Assignment of Rights a. Terminology: X and Y have a K. Y assigns her rights to Z. 1. X = Obligor 2. Y = assignor 3. Z = assignee b. Generally all contractual rights may be assigned 1. Exceptions a. Assigned Rights Would Substantially alter Obligor’s Duty (1) Personal Service Contracts – where obligor would have to perform personal services from someone other than the original obligee (2) Requirements and Output Contracts – generally not assignable because the assignment could change the obligation There are exceptions to this under “good faith” practices or delegation of duties b. Rights Assigned Would Substantially alter Obligor’s Risk (1) Ex. John’s home insured by Acme for loss due to fire. John sells home to Joanne who intends to convert it to a restaurant. Rights cannot be assigned from John to Joanne without consent of Acme. c. Assignment Prohibited by Law – public policy against assignment may be embodied in either statute or case precedent (1) Ex. Many states have laws prohibiting, or at least limiting, wage assignments d. Express Contractual Provision Against Assignment – unless the circumstances indicate the contrary, a clause prohibiting the assignment of “the contract” will be construed as barring only the delegation of the assignor’s duties (R2d 322 & UCC 2-210(4)) c. Effect of Assignment – assignee replaces the assignor as the real party in interest and she alone is entitled to performance under the contract 1. Obligor may usually assert any defense that he can against promisee iii. Delegation of Duties a. Terminology: X and Y have a K. Y delegates duties to Z. 1. X = Obligee 2. Y = Obligor / Delegator 3. Z = Delegate b. Generally all contractual duties may be delegated to a third person 1. Exceptions a. Duties involving personal judgment and skill b. “Special Trust” in Delegator c. Change of Obligee’s Expectancy (1) Ex. Requirements and output contracts d. Contractual Restriction on Delegation (1) Where a contract restricts either party’s right to delegate duties, such a provision will usually be given strict effect c. Rights and Liabilities of Parties 1. Obligee – must accept performance from delegate of all duties that may be performed 2. Delegator – will remain liable on his contract even if delegate expressly assumes the duties a. Novation – when obligee expressly consents to transfer of duties, original obligor may be released from liability 3. Delegate – liability turns on whether there is mere delegation or that plus an assumption of duty a. Delegation – creation of power in another to perform. (1) Obligee cannot compel delegate to perform as they have not promised to perform b. Assumption – delegate promises to perform the duty and the promise is supported by consideration or its equivalent. (1) Obligee can compel performance or bring suit for nonperformance VI. Rules of Contract Construction and The Parol Evidence Rule A. Rules of Contract Construction i. Frequently invoked general rules of construction applied by the courts when interpreting contracts: a. Construed as a Whole – specific clauses will be subordinated to the contract’s general intent b. Ordinary Meaning of Words – unless clearly shown that they were meant to be used in a technical sense c. Inconsistency Between Provisions – written or typed provisions will prevail over printed provisions (which indicate a form contract) d. Custom and Usage – in the particular business industry and in the particular locale where the contract is either made or to be performed (UCC 1-303) e. Preference to Construe Contract as Valid and Enforceable – inclined to construe provisions in such a fashion as to make them operative f. Ambiguities Construed Against Party Preparing Contract – absent evidence of the intention of the parties B. Parol Evidence Rule i. Where the parties to a contract express their agreement in a writing with the intent that it embody the full and final expression of their bargain (i.e. integration), any other expression – written or oral – made prior to the writing, as well as any oral expressions contemporaneous with the writing, are inadmissible to vary the terms of the writing. ii. Designed to carry out the apparent intention of the parties and to facilitate judicial interpretation by having a single clean source of proof (the writing) on the terms iii. Determining whether the writing is an “Integration” of all agreements between parties, ask: a. Is the writing intended as a Final Expression? 1. Do the parties intend such writings to be merely preliminary? a. If so, parol evidence rule will not bar introduction of further evidence 2. The more complete the agreement appears to be on its face, the more likely that it was intended as an integration 3. Whether there is an integrated agreement is determined by the court as a preliminary question (R2d 209) b. Is the writing a Complete or Partial Integration? 1. After determining that the writing was “final”, determine whether it was complete or partial 2. If there was Complete Integration, the contract may not be contradicted or supplemented 3. If there was only Partial Integration, the contract cannot be contradicted but may be supplemented by proving up consistent additional terms 4. Whether agreement is completely or partially integrated is determined by the court as a preliminary question (R2d 210) 5. Where the agreement contains a merger clause reciting that the agreement is complete on its face, this clause strengthens the presumption that all negotiations were merged in the written document c. The judge will decide whether the writing was an integration of all agreements between parties 1. If it was, he will exclude any offered evidence 2. If it wasn’t, he may admit the offered extrinsic evidence 3. Willingston Test: Would parties situated as were these parties to this contract naturally and normally include the extrinsic matter in the writing? a. If yes, evidence of the extrinsic matter will not be admitted b. If no, evidence of the matter may be introduced 4. Wigmore Test: if the extrinsic matter was mentioned or dealt with in the writing, presumably the writing states all that the parties intended to say as to that matter and evidence is excluded d. Extrinsic Evidence Outside Scope of the Rule – since the rule prohibit admissibility only of extrinsic evidence that seeks to vary, contradict, or add to an integration, other forms of extrinsic evidence may be admitted where they will not bring about this result (i.e. they will “fall outside of the scope of the parol evidence rule” (R2d 214) 1. Attacking Validity – party concedes the writing reflects agreement but asserts, most frequently, that the agreement never came into being because of any of the following: a. Formation Defects – may be shown by extrinsic evidence (e.g. fraud, duress, mistake, illegality, lack of consideration, or other invalidating cause) b. Conditions Precedent – where a party asserts that there was an oral agreement that the written condition would not become effective until a condition occurred, all evidence of the understanding may be offered and received (R2d 217) (1) Rationale is that you are not altering a written agreement if it never came into being (2) Distinguish from Condition Subsequent – parol evidence is inadmissible as to conditions subsequent, i.e. an oral agreement that the party would not be obliged to perform until the happening of an event This condition limits or modifies a duty under an existing or formed contract 2. Interpretation – if there is uncertainty or ambiguity in the written agreement’s terms or a dispute as to the meaning of those term, parol evidence can be received to aid the fact-finder in reaching the correct interpretation a. If the meaning is plain, parol evidence is inadmissible 3. Showing of “True Consideration” – parol evidence rule will not bar extrinsic evidence showing the true consideration paid (R2d 218) a. Ex. Contract states that $10 has been given as consideration. Extrinsic evidence will be admitted to show that this sum has never been paid 4. Reformation – where a party to a written agreement alleges facts (e.g. mistake) entitling him to reformation of the agreement, the parol evidence rule is inapplicable a. For ∏ to obtain reformation, he must show: (1) There was an antecedent valid agreement that (2) Is incorrectly reflected in the writing (e.g. mistake) b. The variance must be established by clear and convincing evidence rather than by merely a preponderance of the evidence e. Parol evidence rule applicable only to prior or contemporaneous Negotiations 1. Parol evidence can be offered to show subsequent modifications of a written contract f. UCC Rule 2-202: 1. A writing intended to be a final expression may not be contradicted by evidence of any prior agreement or contemporaneous oral agreement but may be explained or supplemented a. By course of dealing or usage of trade (1-205) or by course of performance (2-208) (even if the terms appear to be unambiguous) b. By evidence of consistent additional terms unless the court finds the writing to have been intended also as a complete and exclusive statement of the terms of the agreement (merger clause?) VII. Interpretation and Enforcement of the Contract A. When Has a Contracting Party’s Duty to Perform Become Absolute? i. Distinction Between Promise and Condition a. Definitions 1. Promise – commitment to do or refrain from doing something a. Unconditional promise is absolute (1) “I promise to pay you $1000 for painting my house” (2) Failure to perform according to its terms is a breach of contract b. Conditional promise may become absolute by the occurrence of the condition (1) “I promise to pay you $1000 if you paint my house” 2. Condition – an event, not certain to occur, which must occur, unless its nonoccurrence is excused, before performance under a contract becomes due (R2d 224) a. “Conditions of Sale” and such language is a term of the agreement, not a condition b. Interpretation of Provision as Promise or Condition – basic test is one of intent of the parties determined by different criteria: 1. Words of Agreement – specific words of the phrase and words of the rest of the agreement 2. Prior Practices – of contracting parties, particularly with one another 3. Custom – with respect to that business in the community 4. Third-Party Performance – if performance is to be rendered by a third party, it is more likely to be a condition than an absolute promise 5. Courts Prefer Promise in Doubtful Situations – most courts will hold that the provision in question is a promise if the situation is doubtful (R2d 227) a. Rationale is that this result will serve to support the contract, thereby preserving the expectancy of the parties b. Particularly significant in situations where breaching party has substantially performed because if provision is a condition, nonbreaching party is completely discharged from obligation, but if provision is a promise, nonbreaching party must perform, although she may recover for the damage she has suffered as a result of the breach (1) **Pipe Case** c. Differences Between Conditions and Promises 1. Failure of condition discharges other party’s duties, breach of promise only gives rise to damages a. Consequences of failure of condition are more severe 2. Breach of promise results in claim for remedy, while failure of condition excuses performance (i.e. is a defense) 3. Conditioning a promise reduces promisor’s risk ii. Classification of Conditions a. According to the Time of Occurrence 1. Condition Precedent – condition that must occur before an absolute duty of immediate performance arises in the other party a. Party’s satisfaction as Condition Precedent – if party has no duty to perform unless “satisfied” with another party’s performance, level of satisfaction depends on the subject matter of the K (1) If the K involves mechanical fitness, utility, marketability, etc., performance is objectively judged and must satisfy a reasonable person (R2d 228) (2) If the K involves personal taste or judgment, performance is judged subjectively and must satisfy the particular party, however that party must act honestly and in good faith 2. Conditions Concurrent – conditions capable of occurring together and that the parties are bound to perform at the same time (e.g. tender of deed for cash) 3. Condition Subsequent – condition that the occurrence of which cuts off an already existing absolute duty of performance 4. Condition Precedent vs. Condition Subsequent – no substantive difference between conditions, important only in regard to burdens of pleading and proof a. Condition Precedent – plaintiff must usually plead and prove because she claims there is a duty to be performed b. Condition Subsequent – defendant must usually plead and prove because he claims the duty that existed no longer exists b. Express, Implied, and Constructive Conditions 1. Express Conditions – those expressed in the contract 2. Implied Conditions – those fairly to be inferred from evidence of the parties’ intention (i.e. determined by contract interpretation) a. Usually referred to as “implied in fact” conditions 3. Constructive Conditions – conditions read into a contract by the court without regard to, or even despite, the parties’ intention a. Done in the interest of fairness to ensure that both parties receive the performance for which they bargained for b. Usually referred to as “implied in law” conditions 4. Effect of Condition – if K is not enforceable due to failure of occurrence of condition, the party who provided benefits can usually recover under unjust enrichment theories (although the measure of damages in that case may be less advantageous than the contract price) c. Have Conditions Been Excused? 1. A promise does not become absolute until the conditions a. Have been performed, or b. Have been legally excused 2. Excuse of Condition by Hindrance or Failure to Cooperate – if party having a duty of performance that is subject to a condition prevents the condition from occurring, she no longer has the benefit of the condition if the prevention is wrongful (not necessary to prove bad faith or malice) 3. Excuse of Condition by Actual Breach – actual breach of K when performance is due will excuse the duty of counterperformance only if the breach is material 4. Excuse of Condition by Anticipatory Repudiation a. Anticipatory Repudiation – promisor, prior to the time set for performance of his promise, indicates that he will not perform when the time comes (R2d 250 and UCC 2-610) b. Anticipatory Repudiation (AR) will excuse conditions when requirements below are met: (1) Executory Bilateral Contract Requirement – AR will only apply where there is a bilateral contract with executory (unperformed) duties on both sides When the non-repudiator has nothing further to do at the moment of repudiation (as in a case of unilateral K or bilateral K fully performed by non-repudiator), the doctrine of AR does not apply (2) Requirement that Anticipatory Repudiation be Unequivocal – promisor must unequivocally indicate that he cannot or will not perform when the time comes, mere expressions of doubt or fear will not suffice (3) Effect of Anticipatory Repudiation – non-repudiating party has four options: (UCC 2-610 and R2d 253) Treat the AR as total repudiation and sue immediately Suspend performance and wait to sue until performance date Treat the repudiation as an offer to rescind and treat the contract as discharged Ignore the repudiation and urge the promisor to perform (4) Repudiation may be retracted until the non-repudiating party has accepted the repudiation or detrimentally relied on it (R2d 256 and UCC 2-611) 5. Excuse of Condition by Prospective Inability or Unwillingness to Perform – when a party has reasonable grounds to believe that the other party will be unable or unwilling to perform when performance is due a. Ex. John contracts with Barbara to buy her house for $150,000. Payment is due on August 1. On July 10, John goes into Bankruptcy (or Barbara transfers title to house to Emily). Prospective inability to perform has occurred. b. Different from AR because involves conduct or words that merely raise doubts that the party will perform c. In judging what conduct may suffice, a reasonable person standard will be applied d. Effect of Prospective Failure is to allow innocent party to suspend further performance until she receives adequate assurances that performance will be forthcoming (R2d 251 and UCC 2-609) (1) If no adequate assurances are given, she may treat as repudiation and may be excused from her own performance e. Retraction is possible if defaulting party regains ability or willingness to perform unless other party has changed her position in reliance on the prospective failure 6. Excuse of Condition by Substantial Performance a. The Rule of Substantial Performance – the condition of complete performance may be excused if the party has rendered substantial performance. Then the other party’s duty of counterperformance becomes absolute b. If breach is material then performance has not been substantial, but if the breach is minor, performance has been substantial c. Most courts will not apply the substantial performance doctrine where the breach has been “willful” d. Nonbreaching party will be able to mitigate by deducting damages suffered due to the first party’s incomplete performance e. UCC perfect tender rule is allows buyer to reject goods that do not conform to the contract in any manner (UCC 2-601) (1) Exceptions: The parties may otherwise agree Rejection of goods under installment K may occur only if there is substantial impairment of value Failure of seller to make reasonable contract with carrier gives buyer to reject only if material delay or loss ensues If buyer has accepted goods he no longer has the right to reject A bad faith rejection by buyer in relation to an immaterial defect may preclude his right of rejection If contract time remains, seller has right to cure 7. Excuse of Condition by Waiver or Estoppel a. Estoppel Waiver – if a party indicates that she is waiving a condition or some performance before it is rendered, and the other party detrimentally relies on such indication, the courts will hold this to be a binding (estoppel) waiver (1) Promise to waive a condition may be retracted at any time before the other party has changes his position to his detriment b. Election Waiver – when a condition or a duty of performance is broken and the beneficiary continues under the contract, she will be deemed to have waived the condition or duty (R2d 246 and UCC 2-606) (1) Requires neither consideration nor estoppel c. Conditions that may be Waived – if no consideration is given for the waiver, the condition must be ancillary or collateral to the main subject and purpose of the K (1) i.e. one cannot waive entire or substantially entire return performance or would be really a gift d. A waiver severs only the right to treat the failure of the condition as a total breach excusing counterperformance, the waiving party still has the right to damages 8. Excuse of Condition by Impossibility, Impracticability, or Frustration of Purpose B. Has the Absolute Duty to Perform Been Discharged? i. Once it is determined that a party is under immediate duty to perform, the duty to perform must be discharged ii. Discharge By Performance – most obvious way to discharge contractual duty iii. Discharge by Tender of Performance – good faith tender of performance made in accordance with contractual terms will discharge duties a. Tendering party must possess present ability to perform (promise insufficient) iv. Discharge by Occurrence of Condition Subsequent v. Discharge by Illegality – if subject matter becomes illegal, performance will be discharged, aka “supervening illegality” vi. Discharge by Impossibility, Impracticability, or Frustration – where the nonoccurrence of the event was a basic assumption of the parties in making the contract and neither party has expressly or impliedly assumed the risk of the event occurring, contractual duties may be discharged a. Discharge by Impossibility – duties will be discharged if it has become impossible to perform them 1. Impossibility must be objective, i.e. could not be performed by anyone 2. Impossibility must arise after the contract has been entered into a. If it already existed when contract was formed, rather a contract formation problem – whether voidable because of mistake 3. Effect of Impossibility – each party is excused from duties arising under the contract that are yet to be fulfilled 4. Partial Impossibility – if performance becomes only partially impossible, the duty may be discharged only to that extent 5. Temporary Impossibility suspends contractual duties, it does not discharge them 6. If part performance has been rendered by either party prior to impossibility, that party will have the right to recover in quasi-contract for the reasonable value of his performance 7. Specific Situations: a. Death or physical incapacity of a person necessary to effectuate the contract serves to discharge it b. If the Ks subject matter is destroyed or the designated means for performing the K are destroyed, duties will be discharged (1) With destruction of subject matter, destruction of a source for fulfilling the contract will render the contract impossible only if the source is the one specified by the parties (2) Discharge because of destruction of subject matter will not apply where the risk of loss has already pass to the buyer b. Discharge by Impracticability 1. Test for Impracticability – the party to perform has encountered: a. Extreme and unreasonable difficulty and/or expense; and b. This difficulty was not anticipated (1) A mere change in the degree of difficulty or expense due to such causes as increased wages, prices of raw materials, or costs of construction, unless well beyond the normal range, does not amount to impracticability because these are the types of risks that a fixedprice contract is intended to cover (R2d 261) 2. UCC allows discharge of seller’s duty to perform where performance may be impractical (UCC 2-615) a. Typical examples of conditions giving rise to “commercial impracticability” include embargoes, crop failure, currency devaluation, war, labor strikes, or the like entailing substantial unforeseen cost increases 3. The rules that apply to temporary and partial impossibility are equally applicable to temporary and partial impracticability c. Discharge by Frustration 1. Frustration will have occurred if: (R2d 265 and UCC 2-615) a. There is some supervening act or event leading to the frustration; b. At the time of entering the contract, the parties did not reasonably foresee the act of event occurring; c. The purpose of the contract has been completely or almost completely destroyed by this act or event; and d. The purpose of the contract was realized by both parties at the time of making the contract vii. Discharge by Rescission a. Mutual Rescission – express agreement between the parties to rescind; this agreement is itself a binding contract supported by consideration 1. Duties must be executory on both sides a. Unilateral Contract – for effective rescission where offeree has already performed, rescission must be supported by: (1) An offer of new consideration by the nonperforming party (2) Elements of promissory estoppel, i.e. detrimental reliance, OR (3) Manifestation of an intent by the original offeree to make a gift of the obligation owed to her b. A mutual rescission on a partially performed bilateral contract will usually be enforced, with the party who has partially performed entitled to compensation depending on the terms of the rescission agreement 2. Formalities – mutual rescission may be made orally even if the contract expressly states that it can only be rescinded by a written document a. Exceptions: (1) If the subject matter falls within the Statute of Frauds then the rescission should generally be in writing Some courts still enforce oral where it is executed or promissory estoppel is present (2) UCC requires written rescission or modification where original contract expressly requires it (UCC 2-209(2)) 3. Where the rights of third party beneficiaries have already vested, contract may not be discharged by mutual rescission b. Unilateral Rescission – where one party desires to rescind the contract but the other desires it to be performed, unilateral rescission may be granted with adequate legal grounds (mistake, misrepresentation, duress, failure of consideration, etc.) viii. Partial Discharge by Modification of Contract – if K is subsequently modified by parties, it will discharge the terms of the modification, not the entire contract, if the following requirements are met: a. Mutual Assent b. Consideration – generally fulfilled because each party has limited his right to enforce the original contract 1. No consideration necessary where modification is merely to correct an error in the original contract 2. No consideration for modification of a contract for the sale of goods (UCC 2209(1)) ix. Discharge by Novation a. Novation – a new contract substitutes a new party to receive benefits and assume duties that had originally belonged to one of the original parties and will serve to discharge the old contract b. Elements for a valid novation: 1. A previous valid contract; 2. An agreement among all parties to the new contract; 3. The immediate extinguishment of contractual duties as between the original contracting parties; and 4. A valid and enforceable new contract x. Discharge by Cancellation – if parties manifest their intent to have such acts serve as discharge, destruction or surrender of a written contract will have this effect if consideration or one of its alternatives is present xi. Discharge by Release – a release and/or contract not to sue will discharge a. Usually must be in writing and supported by new consideration or promissory estoppel elements b. UCC requires an authenticated record (such as a writing) but no consideration (UCC 1-306) xii. Discharge by Substituted Contract – parties enter into a second contract that immediately revokes the first contract a. Revocation may be express or implied 1. Revocation will be implied if the second contract’s terms are inconsistent with the terms of the first contract b. Intent Governs – if parties intend the first contract to be discharged only after performance of the second contract, there is an executory accord rather then a substituted contract xiii. Discharge by Accord and Satisfaction a. Accord – an agreement where one party agrees to accept, in lieu of performance that she is supposed to receive from the other party, some other different performance 1. In general an accord must be supported by consideration a. If consideration is of lesser value than originally bargained-for, it will be sufficient if it is of a different type or if the claim is to be paid to a third party (1) Majority view is that if a party offers a smaller amount than due under original obligation in satisfaction of the claim (i.e. partial payment of original debt), it will suffice for an accord and satisfaction if there is a bona fide dispute as to the claim or there is otherwise some alteration, even slight, in the debtor’s consideration 2. Accord will not discharge original contract but merely suspends the right to enforce it in accordance with the terms of the accord contract b. Satisfaction – performance of the accord agreement, which discharges original and accord contracts c. Effect of Breach of Accord Agreement Before Satisfaction 1. Breach by Debtor – creditor may sue on either the original contract or for breach of the accord agreement 2. Breach by Creditor – i.e. creditor sues on the original contract, debtor may either: a. Raise the accord agreement as an equitable defense and ask that the contract action be dismissed b. Wait until she is damaged (creditor wins action) and then bring action at law for damages for breach of the accord contract d. Checks Tendered as “Payment in Full” – if monetary claim is uncertain or subject to a bona fide dispute, accord and satisfaction may be accomplished by a good faith tender and acceptance of a check when the check (or an accompanying document) conspicuously states that the check is tendered in full satisfaction of the debt (UCC 3-311) xiv. Discharge by Account Stated a. Account Stated – contract between parties to agree to an amount as a final balance due from one to the other 1. Final balance encompasses a number of transactions between parties and serves to merge all of the transactions by discharging all claims owed therein 2. The parties have to have had more than one prior transaction between them b. Writing not usually required unless one or more of the original transactions was subject to the SOF c. Account may be implied, not required that it be express xv. Discharge by Lapse – where a duty of each party is a condition concurrent to the other’s duty, it is possible that on the day set for performance, neither party is in breach and their contractual obligations lapse a. If the contract states that “time is of the essence”, the lapse will occur immediately, otherwise the K will lapse after a reasonable time xvi. Discharge by Operation of Law – where one party obtains a judgment against the other for breach, the contractual duty of performance is merged in the judgment (i.e. damages) thereby discharging the original contract a. Applies also to an award made pursuant to a properly provided-for arbitration b. Discharge in bankruptcy bars any right of action on the contract xvii. Effect of Running of Statute of Limitations – When the statute of limitations has run, it is generally held that an action for breach of contract may be barred a. Only judicial remedies are barred; the running of the statute does not discharge duties (i.e. if party has advantage of the SOL but subsequently agrees to perform, new consideration will not be required) VIII. Breach of the Contract and Available Remedies A. Breach occurs when: i. The promisor is under an absolute duty to perform, and ii. This absolute duty of performance has not been discharged, and iii. There is failure to perform in accordance with contractual terms B. Material vs. Minor Breach i. Effect of Breaches a. Minor Breach – when the obligee gains the substantial benefit of her bargain despite the obligor’s defective performance 1. Effect – provide a remedy for the immaterial breach to the aggrieved party; the aggrieved party is not relieved of her duty of performance b. Material Breach – when obligee does not receive the substantial benefit of her bargain as a result of failure to perform or defective performance 1. The nonbreaching party: a. May treat the contract as at an end, i.e. discharge of duties, and b. Will have an immediate right to all remedies for breach of the entire contract, including total damages c. If a minor breach is coupled with an anticipatory repudiation, the nonbreaching party may treat as a material breach 1. Aggrieved party must not continue on because doing so would be a failure to mitigate damages a. UCC allow party to complete manufacture to avoid having to sell unfinished goods (UCC 2-704) ii. Determining Materiality of Breach a. Generally courts apply the following six criteria (R 275): 1. Amount of Benefit Received – extent to which nonbreaching party will receive substantially benefit anticipated (^E vM) 2. Adequacy of Damages – extent to which injured party may be adequately compensated in damages (^E vM) 3. Extent of Part Performance – extent the party failing to perform completely has already performed or made preparations to perform (^E vM) 4. Hardship to the Breaching Party – extent of hardship on the breaching party should the contract be terminated (^E vM) 5. Negligent or Willful Behavior – extent of negligent or willful behavior of the party failing to perform (^E ^M) 6. Likelihood of Full Performance – extent of likelihood the party who has failed to perform will perform remainder of K (^E vM) b. Failure of Timely Performance 1. If defaulting party had a duty of immediate performance when his failure to perform occurred, then this failure on time will always be a breach of K 2. Additional specific rules for determining the materiality of breach by failure of timely performance: a. As Specified by Nature of Contract – unless nature of K is to make performance on exact day agreed upon vital importance, or by its terms provides time is of the essence, failure by promisor to perform at stated time will not be material b. When Delay Occurs – delay before the delaying party has rendered any performance is more likely to be considered material than delay where there has been part performance c. Mercantile Contracts – timely performance as agreed is important and unjustified delay is important d. Land Contract – more delay in land Ks is required for materiality than in mercantile Ks e. Availability of Equitable Remedy – in equity, courts generally are more lenient in tolerating considerable delay (1) Hence, they will tend to find the breach immaterial and award compensation for the delay where possible C. The nonbreaching party who sues for breach of contract must show that she is willing and able to perform but for the breaching party’s failure to perform D. Remedies for Breach i. Damages a. Types of Damages 1. Compensatory Damages – purpose is to give compensation for the breach, i.e. put the nonbreaching party where she would have been had the promise been performed a. Expectation Damages – generally the standard measure of damages that are based on what the nonbreaching party expected (1) i.e. sufficient damages for her to buy a substitute performance b. Reliance Damages – awarded to the plaintiff if expectation is too speculative or unfit and will measure the plaintiff’s cost of performance (1) i.e. put the plaintiff in the position she would have been in had the contract never been formed c. Consequential Damages – damages holding breaching party liable for any further losses resulting from the breach (1) Further losses have to be those that any reasonable person would have foreseen would occur from a breach at the time of entry into the contract (UCC 2-715) (2) Plaintiff has burden of proof of showing that both parties were aware of the special circumstances that existed at the time of the K formation 2. Punitive Damages – generally not awarded in commercial contract cases but may be awarded in cases where the breach is also a tort (R2d 355) 3. Nominal Damages – token damages (e.g. $1) may be awarded where a breach is shown but no actual loss is proven 4. Liquidated Damages – the contract may provide in advance the damages that are to be payable in the event of breach as long as they are not punitive b. “Standard Measure” – Specific Situations 1. Contracts for the Sale of Goods a. Remedies for Seller (UCC 2-703) – when the buyer wrongfully rejects or revokes acceptance of goods, fails to make a payment due on or before delivery, or repudiates, seller may: (1) Withhold delivery of the goods (2) Stop delivery by the carrier (3) Resell the goods and recover the difference between the resale price and the contract price (4) Cancel the contract (5) Recover the price if: (2-709) Goods have been accepted or conforming goods were lost or damaged within a reasonable time after risk of loss passed to buyer, or Goods have been identified to the contract and the seller is unable to resell (6) Recover ordinary contract damages for nonacceptance, and the measure is the difference between the market price at the time and place for tender and the contract price, together with any incidental damages (2-708) b. Remedies for Buyer (2-711) – if seller fails to deliver or repudiates or the buyer rightfully rejects or revokes acceptance with respect to the goods, the buyer may: (1) Cancel (2) Cover, i.e. buy substitute goods and recover the difference between the price of the substitute goods and the contract price (2-712) (3) Recover goods identified in the contract if the buyer has paid a part or all of the price (4) Recover the goods contracted for if the buyer is unable to cover and the goods were either in existence when the contract was made or were later identified in the contract (5) Obtain specific performance if appropriate (i.e. if goods are unique (2716)) (6) Recover damages for nondelivery which is the difference between the market price at the time when the buyer learned of the breach and the contract price, plus incidental and consequential damages (2-713) Anticipatory Repudiation by Seller – since AR is not a breach until treated as such by the aggrieved party, the courts will usually construe the breach as having occurred at the end of a commercially reasonable time the buyer should await for performance Buyer who Keeps Nonconforming Goods – if seller delivers goods breaching one of his warranties and the buyer decides to keep the goods, the buyer may recover the difference between the value the goods would have had if they had been as warranted and the actual value of the goods (2-714(2)) 2. Contracts for Sale of Land – standard measure for breach of land sales contracts is the difference between the contract price and the fair market value of the land 3. Employment Contracts a. Breach by Employer – irrespective of when breach occurs, standard measure of employee’s damages will be full contract price b. Breach by Employee (1) Intentional Breach – standard is according to what it costs to replace employee Difference between the cost incurred to get a second employee and the cost to the employer had the first breaching employee done the work, offset by work done to date (2) Unintentional Breach – same as intentional but may allow quasicontractual recovery to employee for work done to date 4. Construction Contracts a. Breach by Owner (1) Breach Before Construction Started – profits builder would have derived (2) Breach During Construction – profits plus any costs incurred to date (3) Breach After Construction Completed – full contract price plus interest b. Breach by Builder (1) Breach Before Construction Started – cost of completion (amount above the contract price) plus reasonable compensation for any delay (2) Breach During Construction – cost of completion plus reasonable compensation for any delay If completion would involve undue economic waste, damages will be the difference between the value of what the owner would have received and what the owner actually received Ex. Contract provides that all pipes will be copper. After plumbing is installed but before construction completed, Owner discovers pipes are PVC. The house with PVC pipes would be valued at $500 less than the house with copper pipes but it would cost Builder $10,000 to replace the pipes. Builder would not be compelled to replace the pipes because it would be economic waste and Owner’s damages would be $500 (3) Breach by Late Performance – any loss incurred by not being able to use the property when performance was due (loss of rent, etc.) If damages for lost use are not easily determined or were not foreseeable at the time the contract was entered into, owner can only recover interest on the value of the building as a capital investment 5. Contracts Calling for Installment Payments – this is only partial breach and aggrieved party can only recover the missed payment, not the contract price a. Contract may include an acceleration clause making the entire amount due on any late payment, in which the aggrieved can recover full amount (R2d 243(3)) 6. Duty to Mitigate – All Contracts – when computing standard measure for damages, keep in mind the duty to mitigate c. Certainty Rule – plaintiff must prove that the losses suffered were certain in their nature and not speculative 1. Profits from New Business – generally if breaching party prevented nonbreaching party from setting up a new business, courts would not award lost profits from the prospective business as damages because they were too speculative a. Modern courts may sometimes allow it if they can be made more certain by observing similar businesses in the area or other businesses previously owned by the same party d. Duty to Mitigate Damages 1. The non breaching party has a duty to mitigating damages, and thus must: a. Refrain from piling up losses after she receives notice of the breach b. Not incur further expenditures or costs c. Make reasonable efforts to cut down losses by procuring a substitute performance at a fair price 2. If the nonbreaching party does not mitigate, she will not be allowed to recover those damages that might have been avoided by such mitigation after the breach 3. Generally a party may recover expenses of mitigation 4. Specific Contract Situations: a. Employment Contracts – duty to use reasonable care in finding a position of the same kind, rank, and grade in the same locale (1) Not necessarily the exact same pay level (2) Burden is on employer to show such jobs were available b. Contracts for Sale of Goods (1) Buyer is in Breach – seller has right to resell goods in a commercially reasonable manner (2) Seller is in Breach – buyer has right to purchase substitute goods at a reasonable price c. Manufacturing Contracts – generally if party for whom goods are being made breaches, manufacturer is under a duty to mitigate by not continuing work (1) If facts are such that completion of the manufacturing project will decrease rather than increase damages, the manufacturer has the right to continue d. Construction Contracts – duty to mitigate by not continuing work after breach, but if completion will decrease damages, it will be allowed (1) Builder does not owe a duty to avoid the consequences of an owner’s breach, e.g. by securing other work e. Effect of Liquidated Damages Provision 1. Requirements for Enforcement – parties may stipulate what damages are to be paid in the event of a breach. Those liquidated damages clauses will be enforceable if: a. Damages for the contractual breach must have been difficult to ascertain or estimate at the time the contract was formed b. Amount agreed on must have been a reasonable forecast of compensatory damages in the case of breach (1) Test for reasonableness is a comparison between the amount of damages prospectively probable at the time of contract formation and the liquidated damages figure (2) If amount is unreasonable, courts will construe this as a penalty and not enforce the provision UCC allows a court to consider actual damages to validate a liquidated damages clause even if it was not a reasonable forecast at the time of contract formation (UCC 2-718(1)) 2. If both of the requirements are met, plaintiff will receive the liquidated damages even when no actual money or pecuniary damages have been suffered a. Should one or both of the requirements fail, plaintiff will only recover those damages that she can actually prove 3. If a contract stipulates that a plaintiff can elect to recover liquidated or actual damages, the liquidated damage clause may be unenforceable ii. Suit in Equity for Specific Performance a. Specific Performance – an order from the court to the breaching party to perform or face contempt of court charges 1. Given if the legal remedy is inadequate 2. Generally when the subject matter of the contract is rare or unique b. Available for Land and Rare or Unique Goods 1. Always available for land because land is considered unique 2. Available for goods that are rare or unique at the time performance is due a. e.g. rare paintings, gasoline in short supply because of oil embargoes, etc. c. Not Available for Service Contracts – even if services are rare or unique because it is hard to enforce and possibly unconstitutional (involuntary servitude) 1. Injunction as Alternate Remedy – court may enjoin a breaching employee from working for a competitor throughout duration of contract iii. Restitution a. Restitution is based on preventing unjust enrichment b. Terminology – where a contract is unenforceable or no contract between the parties exists, action to recover restitution damages is an action for an implied in law contract or an action in quasi-contract c. Measure of Damages – generally the measure is the value of the benefit conferred usually based on the value received by the defendant 1. Recovery may also be measured by “detriment” suffered by plaintiff if the benefits are difficult to measure or the “benefit” measure would achieve an unfair result d. Specific Applications 1. Where Contract is Breached a. If nonbreaching party has not fully performed, he may rescind contract and sue for restitution to prevent unjust enrichment b. If nonbreaching party has fully performed, he is limited to damages under the contract even if it may be less than he would have received in restitution c. “Losing Contracts” – a restitution remedy is often desirable in the case of a losing contract (i.e. actual value of services or goods is higher than contract price) because normal contract expectation damages or reliance damages would be for a lesser amount d. Breach by Plaintiff – modern courts will permit restitution of the contract price, less damages incurred by the other party as a result of the breach (R2d 374) 2. Where the Contract is Unenforceable a. Restitution may be available in a quasi-contract action where a contract was made but is unenforceable and unjust enrichment otherwise would result 3. Where No Contract Involved a. Restitution may be available in a quasi-contract action where there is no contractual relationship between the parties if: (1) The plaintiff has conferred a benefit on the defendant by rendering services or expending properties; (2) The plaintiff conferred the benefit with the reasonable expectation of being compensated for its value; (3) The defendant knew or had reason to know of the plaintiff’s expectation; and (4) The defendant would be unjustly enriched if he were allowed to retain the benefit without compensating plaintiff Ex. Doctor witnesses automobile accident and rushes to aid an unconscious victim. Doctor can recover the reasonable value of his services b. Where the parties are in a close relationship it is usually presumed that the benefits were given gratuitously and the party claiming relief bears the burden of showing expectation of being paid