Ch. 22 Performance and Discharge

advertisement

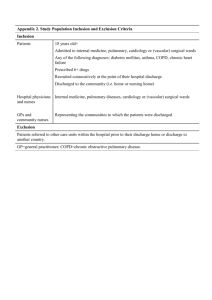

Chapter 22 Performance and Discharge Laura Westensee Edited by Nikki Meltabarger I. Conditions in Contracts Under Common Law, a contract is an agreement involving a promise or set of promises enforceable by law. The Uniform Commercial Code uses this same definition of contract, but in a more limited sense pertaining to the sale of goods. A person who makes an offer is the offeror, while the person to whom the offer is made is the offeree. The offeree is given the power to create a legally enforceable obligation. Once the contract is formed, the parties to the contract now include promisors--those who make a promise--and promisees--those to whom a promise is made. All contracts are subject to conditions. If the terms of the agreement are conditions, then exact performance may be required. A condition may either be breached or met. When a condition is breached, it is not fulfilled. When a condition is met, it is fulfilled. A condition may also be implied or express. Implied conditions are inferred from the nature of the transaction or the conduct of the parties. Express conditions are explicitly stated and included in the terms of the agreement1. The law recognizes the following three kinds of conditions: precedent, concurrent, and subsequent. A. Precedent If the promises made within a contract are not effective until a certain event takes place, a condition precedent exists. The performance of the contract is reliant on a certain event occurring in the future. A party makes a conditional promise that becomes absolute when the condition is fulfilled. A condition precedent assumes each party has “a duty of immediate performance” once the contract is formed2. The performance of the parties, though, does not take place until some point in the future. Condition precedent commonly exists in building contracts, which contain provisions that the contractor will not receive final payment until an architect has issued a certificate that the building has been constructed according to terms of the contract. This approval represents a condition precedent of a legal duty of the promisor to make final payment to the contractor. The courts will usually enforce such conditions. The provisions may be 1 Bandy, William R. Business Law: Text and Cases. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1968 2 Howell, Rate A. An Introduction to Business Law. Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden P, 1974. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 1 waived if the architect has made a gross mistake in calculations or facts when issuing the certificate3. Example: Joe makes this offer to Mary: “If the Cubs win the 2012 World Series, I will pay you $1,000 cash for your signed Cubs baseball jersey.” Mary accepts the offer. A contract has now been formed, but the specified event must occur before either Joe or Mary incurs a duty of immediate performance. B. Concurrent If a contract expresses or infers that the performance of the parties is to occur at the same time, a condition concurrent exists4. Concurrent conditions must be performed at the same time and are mutually dependent. This condition may be expressly stated in the contract or implied from the nature of the contract. Before either party is put at default, the party must make tender of performance. A tender of performance is an offer or attempt by a party to perform his or her part of the contract. This may involve payment of money or performance of an act required under the terms of the contract, such as delivery of goods or services. Business contracts often contain conditions concurrent5. Example: A contract calls for the sale between Tim, the seller, and Harry, the buyer. The seller is to deliver the deed on payment of the purchase price by the buyer. Thus, Tim has no duty to deliver the deed until Harry pays the purchase price and Harry has no duty to pay until Tim delivers the deed. C. Subsequent Under a condition subsequent, both parties to a contract agree to incur a duty of immediate performance, with the exception that if a certain event occurs before the time of performance arrives, the duties are discharged. The language in the contract may express that the contract is “void,” inoperative,” or “canceled” if a certain event occurs in the future6. The 3 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. 4 Howell, Rate A. An Introduction to Business Law. Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden P, 1974. 5 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. 6 Howell, Rate A. An Introduction to Business Law. Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden P, 1974. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 2 contract is subject to discharge upon the occurrence of a specific event or upon the failure of one of the parties to perform a required condition7. The fulfillment of a certain condition discharges one of the parties from his or her duty to perform. If the designated condition is not fulfilled, the party remains under a duty to perform. Manufacturers often write conditional provisions into contracts which relieve them from liability or discharge contractual obligations in the case of fire, strikes, or other natural disasters. They are bound to perform unless a specific hazard or event takes place8. Example: Suzy contracts to sell her liquor store to Jerry for $50,000, with the contract stating that payments are to be made in the amount of $1,000 per month. The contract also contains the condition that if nearby City College permanently closes, the contract will be null and void at the end of the present school year. Jerry has incurred an immediate duty of performance that would be terminated if the college closes. II. Performance Tender of performance is an offer to perform an obligation in fulfillment of the terms of a contract. As long as the tender conforms to the agreement, a tender of performance will discharge the obligation of the one making the tender. When contracts are discharged by performance, each party has completely fulfilled the promise that he or she has made. Therefore, a legal problem does not exist. Under performance, all of the terms of the contract have been fulfilled. Not all of the parties may need to perform at the same time. Parties are discharged from further liability once they have done everything that they agreed to do. Other parties, though, are not discharged if any material performance remains to be done and the contract remains intact. On the other hand, performance may fall short of promises or deviate from the terms of the contract. In this case, the legal consequences of a breach of contract must be determined. To determine these consequences, the degree of performance required of promises must be determined. The degrees of performance of promises include the following: complete performance, substantial performance, and substantial non-performance9. 7 Bandy, William R. Business Law: Text and Cases. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1968 8 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. 9 Schaber, Gordon D. Contracts in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West Company, 1975. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 3 A. Complete The degree of performance is complete for promises that can be discharged only by full performance of the contract. This occurs when each party completely fulfills his or her promise. If a promisor’s performance falls short of the terms of the contract, no matter how minor the breach, contractual duty is not discharged10. A contract may specifically state that the performance must be “satisfactory to” or “to the satisfaction of” a certain person. The extent of satisfactory performance is often a disputed question. In general, the courts have adopted the rule that if the contract is performed in a manner that would satisfy an ordinary, reasonable person, then the terms of the contract have been met satisfactorily to discharge it. Under one exception, a contract may not be discharged if the performance clearly involves the personal taste or judgment of one of the parties on the grounds that it is not satisfactory to that party. Example: In January, Michael contracts to buy a car from Kim for $5,000, with the contract stating that the price is to be paid in full on June 1. On June 1, Michael gives Kim a check for $4,999. Kim has no obligation to transfer the title to Michael. When Michael gives Kim one more dollar to reach a total of $5,000 and Kim in turn gives the car to Michael, performance is completed by both parties and the contract is discharged. B. Substantial Under many obligations, it is not likely or even expected that 100% performance will occur. In a case where less than 100% performance occurs, it is usually determined that the obligation is sufficiently fulfilled if performance conformed to the terms of the contract in all major respects. This is the doctrine of substantial performance. Two requirements must be met for substantial performance to apply. First, the performance must be “substantial.” The courts interpret “substantial” to mean a performance that varies but slightly from the terms of the contract11. The performance must be so nearly complete that it would be unfair to deny the party any compensation for the work. Substantial performance involves an honest attempt to perform without intentional or considerable deviation from the contract12. Second, these variations must not have arisen out of bad faith on the part of the promisor13. If a construction contract is 10 Schaber, Gordon D. Contracts in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West Company, 1975. 11 Schaber, Gordon D. Contracts in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West Company, 1975. 12 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 13 Schaber, Gordon D. Contracts in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West Company, 1975. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 4 substantially performed, the party performing may demand the full price under the contract less the difference between the value according to the contract and the value as constructed14. Example: A builder agrees to build a home according to detailed plans and layout, but the finished home deviates from the specifications in one or more respects. Although the finished home deviates from the terms of the contract, the builder has sufficiently fulfilled his obligation if his performance, flaws and defects included, conformed to the terms of the contract in all major respects. If the value of the home under the contract was $100,000 and the value of the home as constructed was $95,000, the builder is allowed to collect the contract price minus $5,000. C. Substantial Non-performance In a case where less than 100% performance occurs and it is determined that the obligation is not sufficiently fulfilled, the other party can cancel his or her end of the contract and refuse to pay. This will occur if the conditions of substantial performance are not met, specifically if performance did not conform to the terms of the contract in all major respects. Example: A builder agrees to build a home according to detailed plans and layout under a contract in the amount of $100,000. If the builder completed the excavation site for the home and then quit, the builder would be entitled to collect nothing. This would be considered substantial nonperformance, since simple excavation is far from full performance of building the home. III. Perfect Tender Rule for Goods The Perfect Tender Rule for Goods involves the buyer’s right to accept or reject tendered goods. According to the UCC, the buyer has the right to reject “if the goods or the tender of delivery fail in any respect to conform to the contract.” The goods may fail to conform to the contract with regard to quality, quantity, or manner of delivery. If this is the case, the buyer may reject the goods and rescind the contract. The buyer is required to act in good faith, which includes reasonable commercial standards of fair dealings in the trade. The Perfect Tender 14 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 5 Rule for Goods is meant to relieve the buyer of determining whether the defective tender constitutes a major breach15. Example: Larry and Bill enter into a contract for the sale of a television to Bill by Larry. The contract states the television is to be delivered according to packing specifications within three weeks of the date of the contract. Bill receives the television after four weeks without proper packaging. Bill has the right to reject the tendered goods on the terms that the tender of deliver failed to conform to the contract. IV. Time is of the Essence Clause If the contract asserts when performance is to be delivered, these terms must be followed unless performance on the exact date under all circumstances is not vital. When performance on the exact date is vital, it is said that “time is of the essence.” If the contract does not state a time for performance, then performance must be rendered within a reasonable time16. A measure of reasonable time depends upon the nature of the subject matter of the contract. Delivery of perishable goods, for example, would require a much shorter reasonable time for the payment of money than other types of contracts. Courts today generally hold that failure to perform by a time specified in the contract does not necessarily constitute a breach of contract. Under certain contracts, “time is of the essence” is implied. These contracts may include contracts involving perishable goods, corporate securities with fluctuating market values, and payment of debts. When it is determined that the contract is breached due to “time is of the essence,” one party is completely discharged of his obligations and the other party will be liable for damages17. Example: Scott wants to buy toys from Michael for Christmas trade. The contract does not state that “time is of the essence.” Michael does not deliver toys to Scott until January 1 st. In this case, the courts would decide that the parties intended time to be of the essence. Scott would be discharged from his obligations under the contract and Michael would be held liable for damages for breach of the contract. 15 Schaber, Gordon D. Contracts in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West Company, 1975. 16 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 17 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 6 V. Personal Satisfaction Clause A “personal satisfaction clause” is a common provision in contracts that expressly states that a party’s performance depends on the personal satisfaction of the other party. Two categories of satisfaction cases exist. The first category is subjective dissatisfaction and involves situations surrounding personal taste, fancy, or judgment. In this case, the law requires genuine dissatisfaction that must be honest and in good faith. The second category is objective dissatisfaction and includes situations involving mechanical fitness, utility, or marketability. When the satisfaction condition has to do with a situation involving construction or repair, the law requires objective, reasonable satisfaction rather than personal satisfaction. If the average person would be satisfied, then the party is required to perform regardless of how personally dissatisfied he or she is. A majority of cases involving satisfaction concern financial matters and use the reasonableness standard of satisfaction of an average person18. Example: Mark and Dawn form a contract with Mark agreeing to paint Dawn’s portrait to her personal satisfaction for $5,000. The condition precedent that initiates Dawn’s duty to pay is Dawn’s personal satisfaction. If Dawn is genuinely dissatisfied with the painting, she may refuse to pay. No matter how many art experts consider the portrait a masterpiece, Dawn’s performance is conditional upon her subjective dissatisfaction (Corley). VI. Discharge It is important to know when a contract is terminated and when the parties are no longer bound by the contract. In certain cases, a contract can be discharged by law or when the law bars all right of action19. The most common conditions under which the law operates to terminate contracts are the following: rescission, novation, accord and satisfaction, running of the statute of limitations, discharge in bankruptcy, and impossibility. A. Rescission A contract is an agreement voluntarily entered into by contracting parties. Logically, the parties should be permitted to rescind the contract by mutual agreement. Mutual agreement to 18 Corley, Robert N. Principles of Business Law. 14th ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1989. 19 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 7 rescind the contract effectively discharges both parties of their obligations under the contract 20. Under a two-party contract, each party is free to terminate the agreement by a mutual agreement. The surrender of rights by each party is rescission. Rescission may also occur if the parties enter into a new contract which substitutes for the original contract. The original agreement, then, is discharged. Normally, rescissions are expressed in words. In certain cases, though, rescissions may be implied. A failure of both parties in performance of a contract may constitute an implied rescission. Additionally, an unsuccessful negotiation of a contract may also be considered an implied rescission21. Example: Jim enters into a contract to mow Barry’s lawn for two weeks in return for $40 when Barry goes on vacation. For unrelated reasons, Barry’s vacation is canceled. Jim and Barry verbally agree to rescind the agreement, which effectively discharges both parties of their obligations under the contract. B. Novation A party that is entitled to performance under a contract may agree to permit another party to perform the contract, thereby releasing the original party bound by the contract. The old contract must be abandoned and substituted with a new one in its place. The terms of the contract remain the same, but the parties have changed. This is called novation22. Novation involves a substituted contract with at least one new party who replaces, partially or wholly, a party in the previous contract. Novation necessitates at least three parties: the original contracting parties and at least one additional party. A contract is a novation if the following three events occur: the contract discharges a previous duty, the contract creates a new contractual duty, and the contract includes a new party23. It must be made known that a novation was intended. When there is a novation, the new party is now liable for the performance of the contract24. 20 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. 21 Calamari, John D. Contracts. St. Paul: West Company, 1977. 22 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 23 Calamari, John D. Contracts. St. Paul: West Company, 1977. 24 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 8 Example: Carl and Robert have a contract. The contract states that Carl will fix a computer for Robert by June 1. All parties may agree together with Sarah that Sarah will take Carl’s place in fixing the computer for Robert. When this happens, there is a novation and Carl is discharged from the contract. The old contract is abandoned and Robert and Sarah are now parties bound by the new contract. The terms of the contract have not changed and Sarah is bound by the contract to fix the computer for Robert as of June 1. C. Accord and Satisfaction Accord and satisfaction allows discharge of a contract by a performance different from that agreed upon in the agreement. When a party agrees to perform a different promise in place of the original promise, this agreement is an accord. An accord may involve a disputed claim arising in either a tort or a contract25. Satisfaction occurs when the party delivers the promise, thus performing the accord. The satisfaction acts as a discharge of the original promise and the new promise undertaken in the accord agreement26. Accord and satisfaction is a compromise involving a disputed claim. Oftentimes when parties have a disagreement over the contract and the amounts owed, an accord and satisfaction agreement is attempted rather than pursuing litigation27. The principle of accord and satisfaction requires that there be a dispute or uncertainty surrounding the amount due. The parties enter into an agreement for a stated amount as a compromise of their differences. This new agreement satisfies the debt. Laws often have the effect of discharging obligation by prohibiting lawsuits to enforce them. A passage of time without litigation, for example, acts to discharge an obligation28. Example: Gary owes Tim $1,000. Instead, Gary offers to give Tim his car in lieu of the $1,000 and Tim accepts the offer. Gary and Tim have entered into an accord agreement. When Gary performs the accord by delivering the car to Tim, satisfaction occurs. The accord and satisfaction is a discharge of the original obligation to pay the $1,000 and a new obligation of delivering the car to Tim. If Gary does not deliver the car, satisfaction has not occurred and the original obligation remains intact. Tim and Gary still have the right to sue under the original agreement. 25 Corley, Robert N. Principles of Business Law. 14th ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1989. 26 Bandy, William R. Business Law: Text and Cases. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1968 27 Calamari, John D. Contracts. St. Paul: West Company, 1977. 28 Corley, Robert N. Principles of Business Law. 14th ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1989. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 9 D. Statute of Limitations A person’s right to sue must be exercised within a time set by a statute, called a statute of limitations29. Parties can be excused from contractual obligations as a result of the expiration of the period of statute of limitations. Statutes have a fixed period of time in which lawsuits must be initiated. The various statutes of limitations are in place to prevent unfair enforcement of claims after the expiration of a period of time. The reason for statutes of limitations is that evidence may be lost or witnesses may forget beyond the statute period. The state legislature determines the period of time for statutes and they vary by state and type of lawsuit. The UCC designates a limitation period for contracts involving the sale of goods, stating that an action for breach of contract must be initiated within four years after the cause of the action. Some states set a shorter period for unwritten contracts than for written contracts, while others do not. Most of the statutory periods fall between two and six years for unwritten contracts, and between three and twenty years for written contracts 30. For open accounts, accounts receivable, and ordinary loans, the time varies from two to eight years. The time for notes is longer, varying from four to twenty years31. After the limitation period ends, an obligation is considered past and cannot be enforced without the obligor’s consent. If the obligor admits that there is an enforceable obligation, the contract may still be enforceable as originally contracted. In effect, an admission by the obligor restarts the statutory limitation period again. An admission that would renew the limitation period can either be in the form of a clear promise to pay or a partial payment of the obligation by the obligor. If a debtor is sued on an obligation outside the limitation period and fails to claim the defense of statute of limitations, the debtor’s conduct implies that the obligation is enforceable just as if he had explicitly acknowledged the enforceability of the obligation. If a contract includes a provision that the promise is enforceable regardless of how much time passes, most states consider the provision against public policy and ineffective. In other states, the provision may only be effective for a limited time, such as an additional statute of limitations period32. If the promisor leaves the state, the statute stops running while the promisor is outside of the jurisdiction of the court and starts up again if and when the promisor returns. 29 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 30 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 31 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 32 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 10 A debt that has been outlawed by a statute of limitations may be brought back by a written acknowledgement to pay or a part payment of the debt after it has been outlawed. In some cases, the mere payment of interest can revive a debt. The period of the statute of limitations then begins to run from the time of revival33. In the case of failure to pay a promissory note which is due and payable on a specified date, the statute of limitations runs from the maturity date of the note and not from the date the note was executed. In the case of open accounts, the statute runs from the date of the last item of the account, disregarding whether it was debit or credit34. Example: Jack purchased items from Laura on an open account in the District of Columbia. Five years after the last purchase, Jack made two $20 payments on the account. Just less than three years after Jack’s payments, Laura sued to collect the amount owed. Jack defended the suit on the basis of a three-year statute of limitations. The court ruled that on an open account, partial payments made after the statute of limitations has run starts the statute running again. Laura wins the case. Table 1: Statute of Limitations (in years) for Selected Jurisdictions and Types of Contract35 Open Accounts Promissory Notes Oral Contracts Written Contracts California 4 4 2 4 District of Columbia 3 3 3 3 Missouri 5 10 5 10 33 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 34 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. 35 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 11 E. Bankruptcy The affairs of someone in financial difficulty may be settled through a liquidation of assets or through financial rehabilitation. This can be accomplished either with or without court action. The debtor and creditor may make an agreement without court action36. With court action, the law permits individuals and firms to petition the court for a decree of voluntary bankruptcy. Under certain circumstances, creditors may force a party into involuntary bankruptcy37. The affairs may be settled through a state court insolvency proceeding or through a Federal court bankruptcy proceeding. Obligations may be cancelled in the following two ways: 1) by each creditor voluntarily entering into an agreement discharging all unpaid claims, or 2) through a discharge as a result of a bankruptcy proceeding38. In the case of bankruptcy, provable debts are generally dischargeable and rarely paid in full. Creditors’ rights of action to enforce the contracts of the debtor are disallowed after a discharge in bankruptcy has occurred. Not all debts are affected by a discharge in bankruptcy, though. Even after a discharge in bankruptcy, certain wages, future alimony, taxes, unscheduled debts, and claims involving fraud or certain torts remain liabilities. After the final court order frees all listed debts, creditors cannot later recover any part of the debt due to the discharge in bankruptcy39. Only Federal bankruptcy proceedings may discharge the claim of any creditor who refuses to agree to a discharge, a state court insolvency proceeding cannot40. All bankruptcy proceedings take place in the U.S. District courts41. Example: Suzanne is forced into involuntary bankruptcy by several unpaid creditors. Suzanne’s affairs are settled through bankruptcy proceedings. Certain provable obligations are then cancelled through discharge, but her future alimony payments are not discharged. Once her listed debts are freed, these creditors may not later recover any part of the debt owed by Suzanne. 36 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 37 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. 38 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 39 Calamari, John D. Contracts. St. Paul: West Company, 1977. 40 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 41 Dawson, Townes L. Business Law: Text and Cases. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, 1968. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 12 F. Impossibility In the past, courts were inclined to hold persons strictly to their contracts. The duty of courts in contract disputes was limited to defining the terms of agreements, interpreting their meaning, and enforcing them. Professor Morris Cohen describes the role of the courts in present day by saying, “The law must also go beyond the original intention of the parties, to settle controversies as to the distribution of gains and losses that the parties did not anticipate in the same way.” It is good policy at times to allow people to escape from burdensome contracts42. Impossibility of performance is often a method of discharge from a contractual duty. The term impossibility is used to describe a situation in which it has become impossible or extremely unreasonable for the promisor or anyone else to perform the commitment according to the contract43. Conditions can be excused by impossibility when the condition is a material part of the agreed exchange44. Often, contracts are formed on the basis of people possessing special equipment or talents that enable them to perform the contract. If the special equipment or talent is destroyed sometime after the contract is formed, it may become impossible for the owner or person to perform. The test of impossibility means that “it cannot be done” 45. Generally, courts favor excusing a promisor in the case of complete impossibility. Work and service contracts and contracts for the sales of goods are two types of contracts in which questions often arise surrounding impossibility46. The most common causes of discharge by impossibility of performance include the following: destruction of the subject matter, new laws making the contract illegal, or death or physical incapacity of person rendering personal services. If the contract involves specific subject matter, destruction of such subject matter through no fault of the parties discharges the contract by means of impossibility of performance. This rule applies when performance depends on the continued existence of a specified person, animal or thing47. 42 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 43 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 44 Schaber, Gordon D. Contracts in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West Company, 1975. 45 Calamari, John D. Contracts. St. Paul: West Company, 1977. 46 Henszey, Benjamin N. Introduction to Basic Legal Principles. Fourth Ed. ed. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Company, 1986. 47 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 13 Example: An agreement states that Shipping Industries will manufacture and deliver ships ordered by Stan Smith. The next week, the factory where the ships were to be manufactured was completely destroyed by fire and it was impossible to manufacture the ships in time. The destruction of the factory excuses performance for the order. If an act is legal at the time the contract is created but is later made illegal, the contract is discharged (Ashcroft). Example: A construction company is contracted by Jeff to build a service station on Jeff’s property. After the contract is entered into but before building began, the city council passed a zoning ordinance restricting the site of the station to residential purposes. The ordinance discharges the contract. If the contract orders personal services, death or physical incapacity of the party performing, then the services will discharge the contract. A discharge will not apply if the personal services can be readily performed by another person or personal representative of the promisor. These acts may include the painting of a portrait, representing a client in a legal proceeding, or any other highly personal service. If performance is too personal to delegate to another, the death or disability of the bound party will discharge the contract48. Example: A famous opera singer is contracted to perform the opera Carmen. A week before the opera, the singer loses her voice. A substitute performer is not acceptable. The contract between the theater owner and singer cannot be performed, resulting from the test of impossibility. 48 Ashcroft, John D. College Law for Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Co., 1987. Chapter 22: Performance and Discharge Page 14