DISCHARGE OF CONTRACT

advertisement

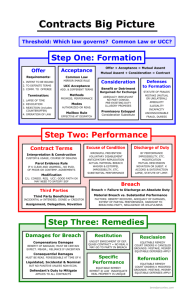

DISCHARGE OF CONTRACT DISCHARGE OF CONTRACT 1. 2. 3. 4. When an agreement, which was binding on the parties to it, ceases to bind them, the contact is said to be discharged. A contract may be discharged in the following ways: By Performance of the contract ; By breach of the contract ; By impossibility of performance ; By Agreement. 1. DISCHARGE BY PERFORMANCE Under a contract each party is bound to perform his part of the obligation. After the parties have made due performance of the contract, their liability under the contract comes to an end. In such a case the contract is said to be discharged by performance. 2. DISCHARGE BY BREACH OF CONTRACT When a party having a duty to perform a contract fails to do that, or does an act whereby the performance of the contract by him becomes impossible, or he refuses to perform the contract, there is said to be a breach of contract on his part. On the breach of contract by one party, the other party is discharged from his obligation to perform his part of the obligation, and he also gets a right to sue the party making the breach of contract for damages for the loss occasioned to him due to the breach of contract. The breach of contract may be either actual, i.e., non-performance of the contract on the due date of performance, or anticipatory, i.e., before the due date of performance has come. For example, A is to supply certain goods to B on 1st January. On 1st January A does not supply the goods. He has made actual breach of contract. On the other hand, if A informs B on 1st December that he will not perform the contract on 1st January next, A has made anticipatory breach of contract ANTICIPATORY BREACH OF CONTRACT It means the repudiation of a contract by one party to it before the due date of its performance has arrived. Section 39, which contains law relating to anticipatory breach of contract is as follows: “ When a party to a contract has refused to perform, or disabled himself from performing, his promise in its entirety, the promisee may put an end to the contract, unless he has signified, by words or conduct, his acquiescence in its continuance.” Anticipatory breach of contract could be made by promisor, either by refusing to perform the contract, or disabling himself from performing the contract in its entirety, before the due date of performance has arrived. When the refusal to perform the contract in its entirety is not there, it is not to be considered to be a case of anticipatory breach within the meaning of section 39. ANTICIPATORY BREACH OF CONTRACT In West Bengal Financial Corporation Vs. Gluco Series AIR 1973 Cal., A granted a loan to B amounting to Rs. 4,38,000 and also agreed to grant a further loan of Rs. 1, 62,000 at its discretion, provided that B made the repayment of the loan in accordance with the agreement at the rate of Rs. 60,000 every year. B failed to make the repayment as agreed. B insisted that A should grant further loan of Rs. 1,62,000 to him, but A did not grant further loan because B did not make the repayment of loan as agreed. B’s contention was that A had failed tom perform the contract by not advancing further loan, which should be considered to be breach of contract. It was, however, held that A had already advanced some loan, which B had accepted, there cannot be said to be a refusal on A’s part to performance of the contract in its entirety. B was therefore not entitled to put an end to the contract on the ground of breach of contract on the part of A . ANTICIPATORY BREACH OF CONTRACT The position is further explained by illustration (b) to section 39, which is under: A, a singer, enters into a contract with B , the manager of a theatre to sing at his theatre two nights in every week during the next two months, and B agrees to pay her 100 rupees for each night’s performance. On the sixth night A wilfully absents herself from the theatre. B is at liberty to put an end to the contract. The above illustration to section 39 may create a misapprehension that in this case absenting on one of the nights is only partial refusal to perform the contract and not failure to perform the contract in its entirety. In Sooltan Chund Vs. Schiller (1879) it was observed that even absence on one night in this illustration is breach of the contract in its entirety. EFFECT OF ANTICIPATORY BREACH OF CONTRACT When the promisor has made anticipatory breach of contract, “the promisee may put an end to the contract, unless he has signified by words or conduct his acquiescence in its continuance.” It means that on the breach of contract by one party, the other party has two alternatives open to him, viz., (i) He may rescind the contract immediately, i.e., he may treat the contract as an end, and may bring an action for the breach of contract without waiting for the appointed date of the performance of the contract, (ii) He may not put an end to the contract but treat it as still subsisting and alive and wait for the performance of the contract on the appointed date. EFFECT OF ANTICIPATORY BREACH OF CONTRACT (i) ELECTION TO RESCIND THE CONTRACT When the promisee accepts the repudiation of the contract even before the due date of performance, and elects to treat the contract at an end, he is discharged from his obligation to perform the contract, and also gets a right to bring an action for the breach of contract, if he so likes, even before the due date of performance has arrived. (i) ELECTION TO RESCIND THE CONTRACT In Hochester Vs. De La Tour (1853) the Defendant engaged the plaintiff on 12th April, 1852, as a courier to accompany him on the tour of Europe. The tour was agreed to begin on 1st June, 1852 and the plaintiff was to be paid £ 10 per month for his services. On 11th May, 1952 the defendant wrote to the plaintiff informing him that he has changed his mind and declined to take the services of the plaintiff. On 22nd May, 1852, the plaintiff brought an action against the defendant for the breach of contract. The defendant contended that there could be no breach of contract before 1st June. It was held that a party to an executory contract may make a breach of contract before the actual date of performance, and the plaintiff, in such a case, is entitled to put an end to the contract and he can bring an action even before the actual date of performance has arrived. The plaintiff’s action therefore succeeded. In Frost Vs. Knight (1872) the defendant promised to marry the plaintiff on the defendant’s father’s death. While defendant’s father was, still alive, he renounced the contract. The plaintiff did not wait till the defendant’s father’s death and immediately sued him, and she was successful in her action. (ii) ELECTION TO KEEP THE CONTRACT ALIVE Anticipatory breach of contract by one party does not automatically put an end to the contract. It has already been noted above that on the anticipatory breach by one party the other party can exercise the option either to treat the contract at an end, or, to treat it as still subsisting until the due date of performance comes. As pointed out by the Supreme Court in the case of State of Kerala Vs. Cochin Chemical Refineries, AIR. 1968, “Breach of contract by one party does not automatically terminate the obligation under the contract : the injured party has the option either to treat the contract as still in existence, or to regard himself a discharged. If he accepts the discharge of the contract by the other party, the contract is at an end. If he does not accept the discharge, he may insist on the performance.” When the contract is kept alive by the promisee, the promisor may perform the same, in spite of the fact that he had earlier repudiated it. If the promisor still fails to perform the contract on the due date, the promisee will be entitled to claim compensation on the basis of the breach of the contract on the agreed date of performance. (ii) ELECTION TO KEEP THE CONTRACT ALIVE Illustration A, a singer, enters into a contract with B, the manager of a theatre, to sing at his theatre two nights in every week during the next two months, and B engages to pay her at the rate of 100 rupees for each night. On the sixth night A wilfully absents herself. With the assent of B, A sings on the seventh night. B has signified his acquiescence in the continuance of the contract, and cannot now put an end to it, but is entitled to compensation for the damage sustained by him through A’s failure to sing on the sixth night (ii) ELECTION TO KEEP THE CONTRACT ALIVE The case of Avery Vs. Bowden (1855) illustrates the point where the promisee elects to keep the contract alive, and the promisor in spite of his earlier repudiation of the contract is discharged from liability because of supervening circumstances before the date of the performance arrives. In this case, A chartered B’s ship at Odessa, a Russian port, and undertook to load the ship with cargo within 45 days. Before this period had elapsed, A failed to supply the cargo and declined to supply the same. The master of the ship continued to insist that the cargo be supplied but A continued to refuse to load. Before the period of 45 days was over, Crimean War broke out between England and Russia, whereby it became illegal to load cargo at a hostile port. The question in this case was, whether by declaration of the war A had been discharged from liability to load the cargo. In this case, on A’s refusal to load the cargo B could have rescinded the contract and brought an action against A, but B instead, by insisting that the cargo be supplied, kept the contract alive. The contact continued to be alive and subsisting for the benefit of both A and B. By the declaration of war, the performance of the contract having become unlawful, it was held that A had been discharged from his duty to supply the cargo, and, therefore, A could not be made liable for nonperformance of the contract. 3. DISCHARGE BY IMPOSSIBILITY OF PERFORMANCE Both under the English and Indian law a contract the performance of which is impossible the same is void for that reason. Section 56, which deals with this question, mentions two kinds of impossibility. Firstly, impossibility existing at the time of the making of the contract. Secondly, a contract which is possible of performance and lawful when made, but the same becomes impossible or unlawful thereafter due to some supervening event. 1. INITIAL IMPOSSIBILITY An agreement to do an act impossible in itself is void. The object of making any contract is that the parties to it would perform their respective promises. If a contract is impossible of being performed., the parties to it will never be able to fulfil their object, and hence such an agreement is void. For example, A agrees with B to discover treasure by magic. The performance of the agreement being impossible, the agreement is void. Similarly, an agreement to bring a dead man to life is also void. 2. SUBSEQUENT IMPOSSIBILITY The performance of the contract may be possible when the contract is entered into but because of some event, which the promisor could not prevent, the performance may become impossible or unlawful. Section 56 makes the following provision regarding the validity of such contracts : “A contract to do an act which after the contract is made, becomes impossible, or by reason of some event which the promisor could not prevent, unlawful, becomes void when the act, becomes impossible or unlawful.” 2. SUBSEQUENT IMPOSSIBILITY It means that every contract is based on the assumption that the parties to the contract will be able to perform the same when the due date of performance arrives. If because of some event the performance has either become impossible or unlawful, the contract becomes void. Section 56 explains this point with the help of following illustrations: A and B contract to marry each other. Before the time fixed for marriage, A goes mad. The contract becomes void. A Contracts to take in cargo for B at a foreign port. A’s Government afterwards declares war against the country in which the port is situated. The contract becomes void when war is declared. A contracts to act at a theatre for six months in consideration of a sum paid in advance by B. On several occasions A is too ill to act. The contract to act on those occasions becomes void. THE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION When the performance of the contract becomes impossible, the purpose which the parties have in mind is frustrated. Because of a supervening event when the performance becomes impossible, the promisor is excused from the performance of the contract. This is known as doctrine of frustration under the English law, and is covered by section 56 of the Indian Contract Act THE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION The basis of the doctrine of frustration was explained by Mukerjea J. in the Supreme Court decision of Satyabrata Ghose Vs. Mugneeram (1954)m in the following words : “ The essential idea upon which the doctrine (of frustration) is based is that of impossibility of performance of the contract ; in fact impossibility and frustration are often used as interchangeable expressions. The changed circumstances make the performance of the contract impossible and the parties are absolved from the further performance of it as they did not promise to perform an impossibility …….. The doctrine of frustration is really an aspect or part of the law of discharge of contract by reason of supervening impossibility or illegality of the act agreed to be done and hence comes within the purview of section 56 of the Contract Act.” THE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION In Taylor Vs. Caldwell (1863) It was held that when the contract is positive and absolute, but subject to an express or implied condition, e.g., a particular thing shall continue to exist, then in such a case, if the thing ceases to exist, the parties are excused from performing the contract. In this case A agreed with B to give him the use of a music hall and gardens for holding concerts on four different dates. B agreed to pay a rent of £ 100 for each of the four days. Before the date of performance arrived, the music hall was destroyed by fire. B sued A for the breach of the contract. It was held that the perishing of the hall without any fault on the part of A had made the performance of the contract impossible and, therefore, A was not liable for the non-performance of the contract. THE DOCTRINE OF FRUSTRATION In Har Prasad Chaubey Vs. Union of India !973 S.C. the appellant was the highest bidder for slack coal belonging to the respondents’ railways. The appellant made full payment for the same. When he applied for the wagons for transporting the coal to Ferozabad, the same was refused by Coal Commissioner on the ground that the coal was meant to be consumed locally only. No such condition existed when the auction of the coal was made. The appellant then filed suit for the refund of the amount paid by him and also interest on the amount on the ground that the contract had become frustrated after the permission to transport the coal was refused. Appellants claim was accepted and he was allowed the refund of the money. The reason for the decision was that the refusal of the Coal Commissioner to allow the movement of the coal to Ferozabad, in spite of the fact that no such condition was there at the time of the auction, had frustrated the contract. CONTRACT NOT FRUSTRATED BY MERE COMMERCIAL DIFFICULTY Merely because the procurement of the goods becomes difficult because of a strike in the mill, or there is a rise in prices, or a person will not be able to earn the expected amount of profits, is not enough to frustrate the contract. In Ganga Saran Vs. Ram Charan, (AIR 1952 S.C.) the defendant agreed to supply 61 bales of cloth of certain specifications manufactured by the New Victoria Mills, Kanpur, to the plaintiff. The agreement by the defendant stated: “We shall continue sending goods as soon as they are prepared to you upto 17-11- 47. We shall go on supplying goods to you of the Victoria Mills as soon as they are supplied to us by the Mill.” As the Mills did not supply the goods to the defendant, he did not supply any cloth to the plaintiff. In an action by the plaintiff for damages for the non-performance of the contract, the defendant contended that the contract had been frustrated by the circumstances beyond his control. It was held the delivery of the goods was not contingent on the supply of goods by the Victoria Mills, and therefore, the contract had not been frustrated by the non-supply of goods to the sellers, by the particular Mills. It was observed: “The agreement does not seem to us to convey the meaning that delivery of the goods was made contingent on their being supplied to the respondent firm by the Victoria Mills. We find it difficult to hold that the parties ever contemplated the possibility of goods not being supplied at all. The words “prepared by the Mill” are only a description of the goods to be supplied, and the expressions “as soon as they are prepared” and “as soon as they are supplied to us by the said Mill” simply indicate the process of delivery …. That being so, we are unable to hold that the performance of the contract had become impossible” RESTORING BENEFIT ON SUBSEQUENT IMPOSSIBILITY It has already been noted above that when, due to the happening of some event, the performance of the contract becomes impossible or unlawful the contract becomes void. Each party is discharged from its obligation to perform the contract. It is just possible that before the contract becomes void, one of the parties may have already gained some advantage under the contract. Such benefit received by a party has to be restored to the other. The relevant provision contained in section 65, which permits such restoration of the benefit, is as under: “When an agreement is discovered to be void, or when a contract becomes void, any person who has received any advantage under such agreement or contract is bound to restore it, or to make compensation for it, to the person from whom he received it” Illustrations (a) A Pays B 1,000 rupees, in consideration of B’s promising to marry C, A’s daughter. C is dead at the time of the promise. The agreement is void, but B must repay A the 1,000 rupees. (b) A contracts with B to deliver to him 250 maunds of rice before first of May. A delivers 130 maunds only before that day, and none after. B retains the 130 maunds after the first of May. He is bound to pay A for them. (c) A, a singer, contracts with B, the manager of a theatre, to sing at his theatre for two nights in every week during the next two months, and B engages to pay her a hundred rupees for each night’s performance. On the sixth night, A wilfully absents herself from the theatre, and b, in consequence rescinds the contract, b must pay a for the five nights on which she has sung. (4) DISCHARGE BY AGREEMENT AND NOVATION Section 62 and 63 deals with contracts in which the obligation of the parties to it may end by consent of the parties. Novation Novation means substitution of an existing contract with a new one. When, by an agreement between the parties to a contract, a new contract replaces an existing one, the already existing contract is thereby discharged, and in its pace the obligation of the parties in respect of the new contract comes into existence. Section 62 contains the following provision in this regard: “62. EFFECT OF NOVATION, RESCISSION AND ALTERATION OF CONTRACT – If the parties to a contract agree to substitute a new contract for it or rescind or alter it, then original contract need not be performed,” Novation is of two kinds : (i) Novation by change in the terms of the contract, and (ii) Novation by change in the parties to the contract (i) CHANGE IN THE TERMS OF THE CONTRACT Then parties to a contract are free to alter the contract which they had originally entered into. If they do so, their liability as regards the original agreement is extinguished, and in its place they become bound by the new altered agreement. For example, A owes B 10,000 rupees. A enters into an agreement with B , and gives B a mortgage of his (A’s) estate for 5,000 rupees in place of the debt of 10,000 rupees. This is a new contract and extinguishes the old. In this illustration the parties to the contract remain the same but there is a substitution of a new contract with altered terms in place of the old one. It may be noted that novation is valid when both the parties agree to it. As the parties have a freedom to enter into a contract with any terms of their choice, they are also free to alter the terms of it by their mutual consent. (ii) CHANGE IN THE PARTIES TO THE CONTRACT It is possible that by novation an obligation may be created for one party in place of another. If under an existing contract A is bound to perform the contract in favour of B , the responsibility of A is bound to perform the contract in favour of B, the responsibility of A could be taken over by C. Now instead of A being liable towards B, by novation C becomes liable towards B . For example, A owes money to B under a contract. It is agreed between A, B and C that B shall thenceforth accept C as his debtor, instead of A. The old debt of A to B is at end and new debt from C to B has been contracted. It may be noted here that in such cases there should be consent of all the three persons, viz., the person who wants to be discharged from the liability, the person who undertakes to be liable in place of the person discharged, and the person in whose favour the performance of the contract is be liable to be made. Thus, if A and B agree that in place of A, now C will be liable, but C does not consent to it, there would be no novation. For example, A owes B 1,000 rupees under a contract. B owes C 1,000 rupees. B orders A to credit C with 1,000 rupees in his books, but C does not assent to the agreement. B still owes C 1,000 rupees and no new contract has been entered into. (ii) CHANGE IN THE PARTIES TO THE CONTRACT The working of the doctrine of novation has been explained by Lord Selborne in Scarf Vs. Jardine in the following words: “That, there being a contract in existence, some new contract is substituted for it either between the same parties or between different parties, the consideration mutually being the discharge of the old contract. A common instance of it in partnership cases is where upon the dissolution of a partnership the person who are going to continue in business agree and undertake as between themselves and the retiring partner, that they will assume and discharge the whole liabilities of the business, usually taking over the assets : and if, in that case, they give notice of that arrangement to a creditor, and ask for his accession to it, there becomes a contract between the creditor who accedes and the new firm to the effect that he will accept their liability instead of the old liability, and on the other hand, that they promise to pay him that consideration.”. REMISSION OF PERFORMANCE Section 63 enables the promisee to agree to dispense with or remit performance of promise. The section reads as under: “ 63. Promisee may dispense with or remit performance of promise – Every promisee may dispense with or remit, wholly or in part, the performance of the promise made to him, or may extend the time for such performance, or may accept instead of it any satisfaction which he thinks fit. REMISSION OF PERFORMANCE Illustrations a) A promises to paint a picture for B. B afterwards forbids him to do so. A is no longer bound to perform the promise. b) A owes B 5,000 rupees. A pays to B and B accepts, in satisfaction of the whole debt 2,000 rupees paid at the time and place at which the 5,000 rupees were payable. The whole debt is discharged. c) A owes B 2,000 rupees, and is also indebted to other creditors. A makes an arrangement with the creditors including B, to pay them a composition of eight annas in a rupee upon their respective demands. Payment to B of 1,000 rupees is a discharge of B’s demand. REMISSION OF PERFORMANCE The section permits a party, who is entitled to the performance of a contract, to i. Dispense with or remit, either wholly or in part, the performance of the contract, or i. accept any other satisfaction instead of performance. (I) DISPENSING WITH OR REMITTING PERFORMANCE The promisee has been authorised, by the above stated provision, to remit or dispense with the performance of the contract without any consideration. He may fully forgo his claim, or may agree to a smaller amount in full satisfaction of the whole amount. Thus, if A promises to paint a picture for B, B may forbid him to do so, or if A owes Rs. 5,000 to B, B may accept from A only Rs. 2,000 in satisfaction of the whole of his claim. In such cases A is discharged so far as the performance of that contract is concerned. It means that if B agrees to accept Rs 2.000 in lieu of Rs 5,000 from A, he cannot thereafter ask a to pay the balance of Rs. 3,000. ACCEPTING PERFORMANCE FROM THIRD PARTY The promisee, if he so likes, may accept performance from a third party, and while accepting such performance he may agree to forgo his claim in part. Once the promisee accepts a smaller amount in lieu of the whole of his claim, the promisor would be thereby discharged. This is clear from the illustration (c) to section 63, which is as follows: A owes B 5,000 rupees. C Pays B 1,000 rupees, and B accepts them, in satisfaction of his claim on A. This payment is a discharge of the whole claim. In Lala Kapuchand Vs. Mir Nawab Himayatali, Khan the position was considered by the Supreme Court to be similar to that contained in illustration (c) to section 63. In this case the plaintiff had a claim of Rs. 27 lakhs against the defendant, the Prince Of Berar In 1949 there was a Police action and Hyderabad was taken over by the military. The Princes Debt Settlement Committee set up by the Military Governor decided that the plaintiff be paid Rs. 20 lakhs in full satisfaction of his claim of Rs. 27 lakhs. The plaintiff accepted the sum of rupees 20 lakhs from the Government in full satisfaction of his claim. He thereafter brought an action against the defendant to recover the balance of Rs. 7 lakhs. It was held that the position was fully covered by section 63, and the plaintiff having accepted the payment from a third person, i.e., the Government, in full satisfaction of his claim had no right to bring an action against the defendant for the balance. (II) EXTENDING THE TIME OF PERFORMANCE Section 63 permits a party to extend the time of performance, and no consideration is needed for the same. The extension of time must be by a mutual understanding between the parties. A promisee cannot unilaterally extend the time of performance for his own benefit. Thus, if a certain date of delivery of goods has been fixed in a contract of sale of goods and the seller fails to supply the goods on such date, the buyer cannot unilaterally extend the time of delivery so as to claim compensation on the basis of rates prevailing on the extended date. He will be entitled to compensate only on the basis of the rates prevailing on the actual date of performance. If the promisee grants the extension of time be becomes bound thereby. Therefore, if the creditor allows some time for making the payment to a debtor, he cannot bring an action against the debtor to recover the debt, and if such an action is brought it will be dismissed by the court as being premature. (III) ACCEPTING ANY OTHER SATISFACTION INSTEAD OF PERFORMANCE Section 63 permits the promisee to accept any other satisfaction in lieu of agreed performance, and this would discharge the promisor. For example, a owes B, under a contract, a sum of money, the amount of which has not been ascertained. A without ascertaining the amount gives b, and B, in satisfaction thereof, accepts, the sum of Rs. 2000. This is a discharge of the whole debt, whatever may be its amount. If the promisee pays less than the amount claimed and the promisor does not consider it to be in full and final satisfaction of his claim, the promisee’s liability under the contract is not discharged, and the promisor is free to sue for the balance. In Union of India Vs. Babulal Uttamchand, AIR 1968 Bom. Some goods belonging to the plaintiffs were lost during transit due to the negligence of the railway administration. The Plaintiffs’ made various claims and the railway administration sent cheques along with printed letters mentioning that the said payments were in full and final satisfaction of the plaintiffs’ claims. The plaintiffs, however, informed the railway administration that this payment was being accepted only as part payment of their claims. In an action to recover the balance of the amount of claims, the defendants pleaded that the plaintiffs could not sue for the balance as the payment already made was in full and final satisfaction of the claims. It was held that the plaintiffs’ suit for the balance of the amount was maintainable, as the amounts were not accepted in full satisfaction of the claim. REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT When one of the parties to the contract makes a breach of the contract the following remedies are available to the other party. 1. Damages : Remedy by way of damages is the most common remedy available to the injured party. This entitles the injured party to recover compensation for the loss suffered by it due to the breach o9f contract, from the party who caused the breach. Section 73 to section 75 incorporate provisions in this regard. REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT 2. Quantum meruit : When the injured party has performed a part of his obligation under the contract before the breach of contract has occurred, he is entitled to recover the value of what he has done, under this remedy. 3. Specific Performance and Injunction : Sometimes a party to the contract instead of recovering damages for the breach may have recourse to the alternative remedy of specific performance of the contract, or an injunction restraining the other party from making a breach of the contract. Provisions regarding these remedies have been contained in the Specific Relief Act, 1963. DAMAGES Section 73 makes the following provisions regarding the might of the injured party to recover compensation for the loss or damage which is caused to him by the breach of contract. Section 73. Compensation for loss or damage caused by breach of contract. – When a contract has been broken, the party who suffers by such breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss or damage caused to him thereby, which naturally arose in the usual course of things from such breach, or which the parties knew, when they made contract, to be likely to result from the breach of it. Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach. DAMAGES Compensation for failure to discharge obligation resembling those created by contract. – When an obligation resembling those created by contract has been incurred and has not been discharged, any person injured by failure to discharge it is entitled to receive the same compensation from the party in default, as if such person has contracted to discharge it and had broken his contract. Explanation :- In estimating the loss or damage arising from a breach of contract, the means which existed of remedying the inconvenience caused by nonperformance of the contract must be taken into account.” DAMAGES The section has been explained with the help of the following illustrations : a) A contracts to sell and deliver 50 maunds of saltpetre to B , at certain price to be paid on delivery. A breaks his promise, b is entitled to receive from A, by way of compensation, the sum, if any, by which the contract price falls short of the price for which B might have obtained 50 maunds of saltpetre of like quality at the time when the saltpetre ought to have been delivered. b) A contracts to let his ship to B for a year from the first of January, for a certain price. Freights rise, and on the first of January, the hire obtainable for the ship is higher than the contract price. A breaks his promise. He must pay to B, by way of compensation, a sum equal to the difference between the contract price and the price for which B could hire a similar ship for a year on and from first January. c) A contracts to repair B’s house in a certain manner, receives payments in advance. A repairs the house but not according to contract. B is entitled to recover from A the cost of making the repairs conform to the contract. DAMAGES In an action for damages for the breach of contract there arise two kinds of problems : 1. Firstly, it has to be determined whether them loss suffered by the p0laintiff is the proximate consequence of the breach of contract by the defendant. The person making the breach of contract is liable only for the proximate consequences of the breach of contract. He is not liable for damage which is remotely connected with the breach of contract. In other words, the first problem is the problem of “Remoteness of Damage.” 2. It is found that the particular damage is the proximate result of the breach of contract rather than too remote, the next question arises is : How much compensation is to be paid for the same? This involves determining the quantum of compensation. This, in other words, is the problem of “Measure of Damages.” REMOTENESS OF DAMAGE The following statement of Alderson B, in case of Hadley Vs. Baxendale (1854) is considered to be the basis of the law to determine whether the damage is the proximate or remote consequence or breach of contract : “Where two parties have made a contract which one of them has broken, the damages which the other party ought to receive in respect of such breach of contract should be such as may be fairly and reasonably be considered either arising naturally, i.e., according to the usual course of things, from such breach of contract itself, or such as may reasonable be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach of it”. REMOTENESS OF DAMAGE The rule in Hadley Vs. Baxendale consists of two parts. On the breach of a contract such damages can be recovered, (1) as may fairy and reasonably be considered arising naturally, i.e., according to the usual course of things from such breach, OR (2) as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties at the time they made the contract. In either case it is necessary that the resulting damage is the probable result of the breach of contract. The principle stated in the two branches of the rule is virtually the rule of “reasonable foresight.” The liability of the party making the breach of contract depends on the knowledge, imputed or actual, of the loss likely to arise in case of breach of contact. The first branch of the rule allows damages for the loss arising naturally, i.e. in the usual course of things from the breach. The parties are deemed to know about the likelihood of such loss. The second branch of the rule deals with the recovery of more loss which results from the special circumstances of the case. Such loss is recoverable, if the possibility of such loss was actually within the knowledge of the parties, particularly the party who makes a breach of the contract, at the time of making the contract. MEASURE OF DAMAGE After it has been established that a certain consequence of the breach of contract is proximate and not remote and the plaintiff deserves to be compensated for the same, the next question which arises is : What is the measure of damages for the same, or in other words the problem is of the assessment of compensation for the breach of contract. Damages are compensatory in nature. The object of awarding damages to the aggrieved party is to put in the same position in which he would have been if the contract had been performed. MEASURE OF DAMAGE In a contract of sale of goods the measure of damages is the difference between the contract price and the market price on the date of the breach of contract. For instance, A agrees to supply B a radio set on January for Rs. 1,000. If A fails to supply the radio set and the market price of the radio set on that date is Rs. 1,200, B will be entitled to recover from A Rs. 200 as damages. The reason is that the loss suffered by the buyer is Rs. 200 because due to the rise in the market price of the radio set he will have to pay that much extra if he purchases the radio set from the market. Similarly, if the buyer (B) refuses to take the radio set on the due Date, the seller will also be entitled to recover the difference between the contract price and the market price on 1st January. For instance the market price of the radio set on that date is Rs. 800, A’s loss is Rs.200 in respect of the transaction, because from another customer A can get only Rs. 800 whereas B had promised to pay Rs. 1,000 for the same. A can recover Rs. 200 from B.. MEASURE OF DAMAGE The rule in this regard was stated in Borrow Vs. Arnaud (1844) in the following words. “ Where a contract to deliver goods at a certain price is broken the proper measure of damages in general is the difference between the contract price and the market price of such goods at the time when the contract is broken, because the purchaser having the money in his hands, may go into the market and buy. So, if a contract to accept and pay for the goods is broken, the same rule may be properly applied, for the seller may take his goods into the market and obtain the current price for them.” QUANTUM MERUIT Ordinarily if a person having agreed to do some work or render some service has done only a part of what he was required to do, he cannot claim anything for what he has done. When a person agrees to complete some work for a lump sum non-completion of the work does not entitle him to any remuneration even for the part of the work done. But the law recognises an important exception to this rule by way of an action for ‘Quantum Meruit’ Under this section if A and B have entered into a contract, and A, who has already performed a part of the contract, is then prevented by B from performing the rest of his obligation under the contract, A can recover from B reasonable remuneration for what ever he has already done. QUANTUM MERUIT It may be noted that this action is not an action for compensation for breach of contract by the other side. It is an action which is alternative to an action for the breach of contract. This action in essence is one of restitution, putting the party injured by the breach of contract in a position in which he would have been had the not been entered into. It merely entitles the injured party to be compensated for whatever work he may have already done, or whatever expense he may have incurred. In the words of Alderson, B, Where one party has absolutely refused to perform, or has rendered himself incapable of performing, his part of the contract, he puts it in the power of the other party either to sue for the breach of it or to rescind the contract and sue on a quantum meruit for the work actually done.” QUANTUM MERUIT The essentials of an action of quantum meruit are as follows : 1. One of the parties makes a breach of contract, or prevents the performance a part of it by the other side. 2. The party injured by the breach of the contract, who has already performed a part of it, elects to be discharged from further performance of the contract and brings an action for whatever he has already done. For instance, if A agrees to deliver B 500 bags of wheat and when A has already delivered 100 bags B refuses to accept any further supply, A can recover from B the value of wheat which he has already delivered. QUANTUM MERUIT In De Bernardy Vs. Harding, (1853) the defendant, who was to erect and le seats to view the funeral of the Duke of Wellington, appointed the plaintiff as his agent to advertise and sell tickets for the seats. The plaintiff was to be paid commission on the tickets sold by him. The plaintiff incurred some expense in advertising for the tickets but before any tickets were actually sold by him his authority to sell tickets was wrongfully revoked by the defendant. It was held that the plaintiff was entitled to recover the expenses already incurred by him under an action for quantum meruit.