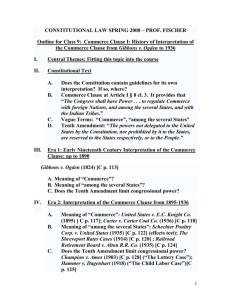

Power Point Chapter 4

advertisement

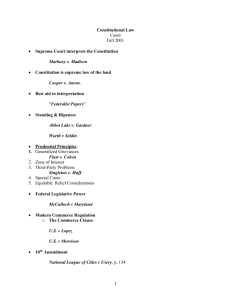

CHAPTER 4 Business & the Constitution What is the U.S. Constitution? The U.S. Constitution, adopted in 1789, is a written document establishing the structure and powers of American government, and it is the “supreme law of the land” (Art. VI, sec. 2) 6-2 What is the U.S. Constitution? The federal government has a constitution and each state has its own constitution. The North Carolina Constitution can be found at: http://www.ncga.state.nc.us/Legislation/constitution/ncc onstitution.html Many other countries have either no constitution or no written constitution. When American judges/attorneys/law professors speak of “the Constitution” they are usually referring to the United States constitution. 6-3 Separation of Powers Separation Of Powers Horizontal- 3 Branches Of Gov’t Vertical- Federalism As Justice Brandeis once said, “The doctrine of separation of powers was adopted by the Convention of 1787, not to promote efficiency, but to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power. The purpose was, not to avoid friction, but by means of the inevitable friction incident to the distribution of the governmental powers among 3 departments, to save the people from autocracy.” 6-4 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause Preemption: The U.S. Constitution is “the supreme law of the land”, therefore, all laws, acts, and decisions not in conformity with it are null and void. (see chart on p.145 for examples of preemption) Savings Clause GEIER v. AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR COMPANY, INC. 120 S.Ct. 1913 (2000) • FACTS: Geier sued American Honda Motor Company, Inc. after she sustained injuries when her 1987 Honda collided with a tree. Geier’s car had shoulder and lap belts but no airbags. Geier claims that Honda should have equipped the car with airbags and is liable because it did not. Honda relies on federal statutes and regulations to absolve it from liability since the federal authorities did not require, but permitted, the installation of airbags in 1987 model cars. 6-5 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause Savings Clause GEIER v. AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR COMPANY, INC. 120 S.Ct. 1913 (2000) • ISSUES: • 1. Does the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 preempt Geier’s lawsuit? • 2. Does the 1984 version of the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS 208) preempt Geier’s suit? 6-6 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause Savings Clause GEIER v. AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR COMPANY, INC., 120 S.Ct. 1913 (2000) • DECISION: • 1. No. The 1966 Act does not preempt the lawsuit because it has a savings clause that “does not exempt any person from liability under common law.” • 2. Yes. There exists a conflict between the FMVSS 208 safety standard allowing manufacturers discretion whether to install airbags in 1987 models and a lawsuit claiming the manufacturer is liable for failing to install airbags. The conflict is resolved by finding the federal safety standard preempts the state-based lawsuit. 6-7 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council, p.79 The Massachusetts statute that barred the state from buying goods or services from companies that did business in Burma (Myanmar) was unconstitutional. The state law was preempted by federal law. The state statute undermined the accomplishment of the full purposes of the federal. If something is to be done about problems like that occurring in Burma, it is up to the federal government to issue the necessary rules. 6-8 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • Barnett Bank bought a Florida licensed insurance agency. The State of Florida Insurance Commissioner ordered Barnett Bank to stop selling insurance. Florida law prohibits any bank which is affiliated with other banks from selling insurance. Barnett Bank sought a declaratory judgment that the federal law preempts Florida’s law. A 1916 federal law allows banks in small towns (with less than 5,000 in population) to sell insurance. Issue: Does the federal law preempt the Florida law? Held: Yes. There is a conflict between the meaning of the federal and Florida laws. This conflict cannot be reconciled by enforcing both laws. The federal law preempts the Florida law under the Supremacy Clause. Barnett Bank of Marion County, N.A. v. Nelson, 116 S.Ct. 1103 (1996). 6-9 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • A New York statute requires hospitals to collect a surcharge from patients covered by certain commercial insurers and HMOs. Insureds under Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans were not subject to the surcharge. Several insurance companies and HMOs brought this action contending that the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) preempted the area of health insurance when such coverage is purchased by an employee health-care plan governed by ERISA. Issue: Are the health plans subject to the New York law sufficiently related to employee benefit plans to fall within ERISA's preemption? Held: No. New York's surcharges affect only indirectly the relative prices of insurance policies. This result is no different from many state laws in areas traditionally subject to local regulation. Congress could not possibly have intended to eliminate all of these areas of regulation. New York Blue Cross Plans v. Travelers Inc., 115 S.Ct. 1671 (1995). 6-10 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • The U.S. Labor Department sought to enforce minimum wage and overtime pay standards against the mass transit system in San Antonio, Texas. The case sought a reversal of National League of Cities. Issue: Does the federal law apply to these employees of a local transit system? Held: Yes. Public transit authorities are required to comply with the overtime provisions of federal law pursuant to congressional power to regulate interstate commerce. Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority, 105 S.Ct. 1005 (1985). 6-11 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • The FCC regulates cable television. Oklahoma prohibited the broadcasting of advertisements for alcoholic beverages. Issue: Does the FCC preempt state regulation of TV advertising? Held: Yes. Under supremacy clause, enforcement of state regulation may be preempted by federal law in several circumstances, i.e., first, when Congress, in enacting federal statute has expressed clear intent to preempt state law, second, when it is clear, despite absence of explicit preemptive language, that Congress has intended, by legislating comprehensively, to occupy entire field of regulation and has thereby left no room for states to supplement federal law, and, finally, when compliance with both state and federal law is impossible or when state law stands as an obstacle to accomplishment and execution of full purposes and objectives of Congress. Capital Cities Cable, Inc. v. Crisp, 104 S.Ct. 2694 (1984). 6-12 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • Arizona had a statute which provided for the suspension of licenses of drivers who were unable to satisfy judgments even if bankrupt. P had filed a voluntary petition in bankruptcy and had duly scheduled a judgment debt arising out of a traffic accident. The court in bankruptcy discharged P. P filed a complaint seeking to retain a driver's license. Issue: Is the Arizona law in conflict with the federal bankruptcy law? Held: Yes. The Arizona statute is unconstitutional. The two provisions are in direct conflict. The purpose of the Bankruptcy Act is to give debtors new opportunity unhampered by the pressure and discouragement of preexisting debt. The challenged state statute stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress. Perez v. Campbell, 91 S.Ct. 1704 (1971). 6-13 The Supremacy Clause Supremacy Clause • Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America v. Walsh, 123 S.Ct. 1855 (2003) (Maine prescription drug program does not violate commerce clause and is not preempted by federal Medicare program); Livadas v. Bradshaw, 114 S.Ct. 2068 (1994) (preemption by the National Labor Relations Act) and Wisconsin Public Intervenor v. Mortier, 111 S.Ct. 2476 (1991) (no preemption by the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act). 6-14 Federal Preemption Types of Federal Preemption State Law Is Unconstitutional If . . . Express preemption The federal law contains a provision superceding all state laws. Field preemption It can be implied from various factors, such as the scope of the federal law, that Congress intended to preempt the field. Conflict preemption The federal and state laws actually conflict. The Contract Clause Contract Clause “No State shall … pass any law impairing the obligation of contracts.” Note: This does not apply to the federal government Under the contract clause, the threshold inquiry is whether the state law has, in fact, operated as substantial impairment of contractual relationship; the severity of impairment is said to increase the level of scrutiny to which legislation will be subjected. 6-16 The Contract Clause Contract Clause • Factors that may justify a state law that • • • • • impairs private contract rights are: a. The law is enacted in an emergency situation. b. The law is broad to protect basic societal interests. c. The relief is properly tailored to meet those interests. d. The conditions of the law are reasonable. e. The law is limited to the duration of an emergency. 6-17 The Contract Clause Contract Clause • In 1980, Congress amended ERISA to require employers withdrawing from a multiemployer pension plan to pay a fixed amount to cover unfunded benefits. The law was made retroactive. Issue: Is this application constitutional under the contract clause? Held: Yes. The contract clause does not apply, either by its own terms or by convincing historical evidence, to actions of the national government. Pension Ben. Guar. Corp. v. R.A. Gray & Co., 104 S.Ct. 2709 (1984). 6-18 The Contract Clause Contract Clause • A state regulation restricted the income of a utility. Issue: Is this state regulation a violation of the contract clause? Held: No. The law does not necessarily constitute substantial impairment for purposes of the contract clause. If a substantial impairment is found, the state, in justification, must have a significant and legitimate public purpose behind the regulation. Once such a purpose has been identified, the adjustment of the contracting parties' rights and responsibilities must be based upon reasonable conditions and must be of a character appropriate to the public purpose justifying the legislation's adoption. Energy Reserves Group, Inc. v. Kansas Power & Light Co., 103 S.Ct. 697 (1983). 6-19 The Commerce Clause “Congress shall have Power … to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes…” Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution. 6-20 The Commerce Clause 1) Federal Regulation a) Foreign Commerce b) Interstate Commerce Engaged in & Affecting Undue Burden Discrimination Against 6-21 The Commerce Clause The power to regulate interstate commerce was first defined in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). In that case, Ogden had a ferry license, gave him right to operate steam boats to and from N.Y argued Gibson’s federal “coasting license” didn’t include “landing rights” in New York. The Court invalidated the New York licensing regulations saying that federal regulation should take precedence under the Supremacy Clause. This decision strengthened the power of the U.S to regulate any interstate business relationship. 6-22 The Commerce Clause The expansion of the power to regulate private businesses began with Wickard v. Fillburn (1942) wherein the Court decided Congress may regulate any activity that has a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce. In that case, the Court held that wheat production by an individual farmer, intended wholly for consumption on his own farm was still subject to Federal regulation because the overall demand for wheat was reduced by the farmer’s actions.6-23 The Commerce Clause Later, in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. U.S. (1964), the Court held that a motel that provided public accommodations to guests from other states was subject to federal civil rights legislation. 6-24 The Commerce Clause Today, the Commerce Clause authorizes the national government to regulate virtually any business enterprise, including internet. 6-25 The Commerce Clause Discrimination Against Interstate Commerce SOUTH CENTRAL BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY v. ALABAMA, 119 S.Ct. 1180 (1999) FACTS: South Central Bell files this suit claiming the franchise tax imposed by the State of Alabama is unconstitutional under the Commerce Clause. The company argues the tax discriminates against businesses that are not formed under Alabama law. The State of Alabama asserts that although the formulas used to determine the amount of tax are different for in-state and out-of-state companies, the result of such taxes are not discriminatory. ISSUE : Is the Alabama franchise tax unconstitutional? 6-26 The Commerce Clause Discrimination Against Interstate Commerce SOUTH CENTRAL BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY v. ALABAMA, 119 S.Ct. 1180 (1999) DECISION: Yes. Under the Commerce Clause, a state regulation of business activity must not discriminate against those businesses engaged in interstate commerce. The Court finds that Alabama allows instate companies to determine their capitalization through setting the par value of company stock. Since the in-state businesses are taxed based on the amount of capital, these companies can avoid some or all of the tax. Since out-of-state businesses don’t have this same opportunity to adjust the amount of tax paid, the franchise tax is discriminatory and unconstitutional. 6-27 The Commerce Clause Discrimination Against Interstate Commerce An Oklahoma law required coal-fired electric power plants to use Oklahoma-mined coal for at least 10 percent of their fuel needs. Previously, four Oklahoma utilities had purchased almost all of their coal from Wyoming sources. Wyoming brought suit against Oklahoma for damages contending that the law caused it to lose coal severance taxes. Issue: Does Wyoming have standing to sue? Held: Yes. A state's loss of tax receipts due to another state's economic legislation gives it standing to mount a Commerce Clause challenge to that law. Wyoming v. Oklahoma, 112 S.Ct. 789 (1992). 6-28 The Commerce Clause Discrimination Against Interstate Commerce A state law required out-of-state beer distributors to attest that the prices charged in the state are no higher than the prices in bordering states. Issue: Is this a violation of the Commerce Clause? Held: Yes. It forces the distributors to take one state's law into account in setting prices in neighboring states. Healy v. Beer Institute, 109 S.Ct. 2491 (1989). 6-29 Supreme Court Tests For Interstate Commerce Before the late 1930s: • Did the regulated activity have a direct rather than indirect impact on interstate commerce? • Did the regulated activity concern something that was in the stream of commerce? Current tests: • Does the regulation affect a channel of interstate commerce? • Does the regulation affect an instrumentality of interstate commerce? • Does the regulated activity have a substantial impact on interstate commerce? The Commerce Clause 2) Limitation a) State Police Power Health, Safety, Morals & General Welfare Exception: Nationwide Uniformity e.g. FAA 6-31 State Police Power Power • Protect Public • Dominant Commerce Clause Exclusively • Federal • Local Dual Regulation • Federal Preemption • Regulation But No Preemption Irreconcilable Conflicts Undue Burden • No Federal Regulation 6-32 State Police Power State has inherent “police powers.” • Police powers include right to • regulate health, safety, morals and general welfare. Includes licensing, building codes, parking regulations and zoning restrictions. 6-33 The Commerce Clause Police Power Raich v. Ashcroft, p.82 • Federal legislation made it unlawful to traffic in marijuana. It was applied against California residents (where state law permits marijuana use for medical purposes) who were using, or supplying the marijuana, for medical purposes. The court held that application of the law against these people was unconstitutional because it was not an activity that Congress could regulate under the Commerce Clause. 6-34 The Commerce Clause Police Power - Limitation In United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. at 552 (1995), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a statute prohibiting possession of a gun at or near a school, rejecting an argument that possession of firearms in school zones can be punished under the Commerce Clause because it impairs the functioning of the national economy. Acceptance of this rationale, the Court said, would eliminate "a[ny] distinction between what is truly national and what is truly local," would convert Congress' commerce power into "a general police power of the sort retained by the States," and would undermine the "first principle" that the Federal Government is one of enumerated and limited powers. Application of the same principle led five years later to the Court's decision in United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000), invalidating a provision of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) that created a federal cause of action for victims of gender-motivated violence. Congress may not regulate "non-economic, violent criminal conduct based solely on that conduct's aggregate effect on interstate commerce," the Court concluded. "[W]e can think of no better example of the police power, which the Founders denied the National Government and reposed in the States, than the suppression of violent crime and vindication of its victims." 6-35 The Commerce Clause Dormant Commerce Clause Washington v. Heckel, p.80 The court held that Washington’s statute prohibiting the out-of-state spam from being emailed into the state did not unconstitutionally burden interstate commerce. The state law had clear local benefits and only burdened spammers by requiring that they be truthful in their commercial communications. Points for The case lays out the analytical scheme for examining the dormant commerce clause. Note that early cases narrowly interpreted the Commerce Clause, focusing more upon its negative power over state regulation and restricting the federal government’s power to regulate business. Subsequent decisions, however, significantly broadened the federal power to regulate business by recognizing the federal government’s power to regulate activities having a “substantial relationship” to interstate commerce. 6-36 The Commerce Clause Dormant Commerce Clause Granholm v. Heald, 544 U.S. ___(2005) The Supreme Court by a 5-4 majority ruled unconstitutional laws in New York and Michigan that permitted in-state wineries to ship wine directly to consumers, but prohibited out-of-state wineries from doing the same. 6-37 State Taxation Form Of Regulation Limited By Commerce Clause Apportionment Must Be Sufficient TieNexus Or Taxable Situs 6-38 Commerce Clause 2) Limitation b) State Taxation • HUNT-WESSON, INC. V. FRANCHISE TAX BOARD OF CALIFORNIA, 120 S.Ct. 1022 (2000) FACTS: California attempted to apportion Hunt-Wesson’s and similarly situated companies’ income to determine what part properly was subject to California’s income tax. California limited companies’ use of a deduction for interest payments by offsetting such payments by the amount of income from non-related (nonunitary) business activities. Hunt-Wesson challenged this limitation of the interest deduction since the income from nonunitary sources were unrelated to California. ISSUE: Does California’s exception to the interest deduction violate the constitutional requirements of nexus needed to justify a state’s taxation of interstate commerce? 6-39 Commerce Clause 2) Limitation b) State Taxation HUNT-WESSON, INC. V. FRANCHISE TAX BOARD OF CALIFORNIA, 120 S.Ct. 1022 (2000) DECISION: Yes. California fails to establish a reasonable nexus or connection between its tax on the income earned outside the state. Because there is a lack of nexus, the California limitation on use of the interest deduction violates the Commerce Clause. 6-40 Commerce Clause The Massachusetts Commissioner of Food and Agriculture implemented a system of assessments and distribution of collected funds in an attempt to support dairy farmers. West Lynn Creamery purchases approximately 97% of the raw milk it buys from out-of-state dairy farmers. Upon being assessed a “premium payment” based on the total amount it handles, West Lynn and one of its customers, LeComte’s Dairy, inc., challenged the Commissioner’s plan as in violation of the Commerce Clause. The Massachusetts courts found the Commissioner’s program was constitutional. Issue: Does the Massachusetts program of assessments and distribution of funds discriminate against out-of-state milk producers? Is this program unconstitutional in violation of the Commerce Clause? Held: Yes to both questions. The Massachusetts pricing program imposes a “tax” which makes out-of-state milk more expensive to produce. The program enables higher-cost Massachusetts dairy farmers to compete with lowercost out-of-state dairy farmers. West Lynn Creamery, Inc. v. Healy, 114 S.Ct. 2205 (1994). 6-41 Foreign Commerce Federal Gov’t Has Exclusive Right To Regulate Foreign Commerce State Can Regulate Commerce If Occurs Entirely Within State Boundaries 6-42 Takings Clause Ridge Line v. United States, p.85 The government owned property adjacent to a privatelyowned shopping center. After the government built a Post Office on its lot, an increase in storm water run-off caused considerable damage to the shopping center. The appellate court held that the trial court was incorrect in holding that no compensable taking had occurred because the lower court wrongly found there to be no permanent and exclusive occupation by the government. The appellate court concluded that a permanent occupation need not exclude the property owner to be compensable and need not be continuous. 6-43 Takings Clause Kelo v. New London, 125 S.Ct. 2655 (2005) The city used eminent domain to condemn privately owned real property so that it could be used as part of a comprehensive redevelopment plan. The Court held that "the city's proposed disposition of this property qualifies as a 'public use' within the meaning of the Takings Clause of the 5th Amendment." 6-44 Bill of Rights The “Bill of Rights”, or first 10 amendments to the Constitution, drafted in 1789, states in its preamble, as its fundamental purpose: “THE Conventions of a number of the States, having at the time of their adopting the Constitution, expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the Government, will best ensure the beneficent ends of its institution.” 6-45 Bill of Rights In addition, the 10th amendment states: • “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” 6-46 Bill of Rights The “Plain Language” of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution and the first 10 Amendments appear to suggest that the limitations contained therein were intended to be limitations upon the actions of the federal government, not upon actions of state governments, and clearly not upon the actions of individual citizens. 6-47 First Amendment Freedoms: • Religion • Press • Speech • Assembly Right To Petition For Redress 6-48 Freedom Of Religion The first amendments states: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. 6-49 Freedom Of Religion In Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. (7 Pet.) 243 (1833) and Permoli v. New Orleans, 44 U.S. (3 How.) 589 (1845), the U.S. Supreme Court specifically held that the Free Exercise clause of the First Amendment was inapplicable to the states. 6-50 Fourteenth Amendment Section 1 of Fourteenth Amendment, passed by Congress following the American Civil War on, June 13, 1866 and ratified July 9, 1868 states: • “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” 6-51 Fourteenth Amendment Section 5 of Fourteenth Amendment, adds that: “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” 6-52 Fourteenth Amendment The “Privileges and Immunities”, “Due Process” and “Equal Protection” clauses of this section have all been used in varying contexts to support the argument that some or all of the limitations placed upon the federal government by the Bill of Rights should also be extended to state governments. This is commonly known as the doctrine of “incorporation”. 6-53 Privileges and Immunities Privileges & Immunities: Art. IV, Sec. 2, Clause 1 states that the “citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.” • Therefore, each state must offer same privileges to a person from another state as it would to its citizens • For business, that essentially means that rights established under deeds and contracts and court orders in one state will be honored by other states 6-54 Incorporation Doctrine—Timeline 1833 The Bill of Rights did not apply to state and local governments. 1857 Slaves were not citizens and not entitled to any constitutional protection. 1868 States were prohibited from denying their citizens due process, equal protection, or privileges and immunities. 1872 The Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not incorporate any of the Bill of Rights. 1864 In holding that due process did not require a grand jury hearing, the Supreme Court did not rule out the possibility that some of the Bill of Rights might be included in the concept of due process. 1908 Rights that are a fundamental principle of liberty and justice, which inhere in the very idea of free government, and are the inalienable rights of a citizen of such a government are protected by due process. (Here, due process did not apply to self-incrimination, although this was later changed.) Current View The Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause extends most of the Bill of Rights protections against action by State (the Incorporation Doctrine). Incorporation Doctrine The first time the incorporation doctrine was utilized to make the restrictions of the First Amendment applicable to state and local governments was in the 1940 case of Cantwell v. Connecticut. In Cantwell, a Jehovah's Witness was arrested in the course of proselytizing on the streets of New Haven, and was convicted for inciting a breach of the peace. The Supreme Court reversed the conviction and found that Cantwell's behavior did not breach the peace. The Court went on to state that the statute he was convicted under was sweeping and included a great variety of constitutionally protected conduct, including Cantwell's free exercise of religion. 6-56 Incorporation Doctrine Later in Everson v. Board of Ed., 330 U.S. 1 (1947), the U.S. Supreme Court, citing Cantwell and other Free Exercise and Free Speech cases, held that the Establishment Clause was incorporated and made applicable to the States via the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment. 6-57 Freedom of Religion Frazee refused a temporary position offered to him by Kelly Services because the job would have required him to work on Sunday. He was denied unemployment compensation benefits since he was not a member of an established religious sect or church and did not claim that his refusal to work resulted from a tenet, belief, or teaching of an established religious body. Issue: Does the denial of compensation constitute a violation of the Free Exercise Clause? Held: Yes. While membership in a sect would simplify the problem of identifying sincerely held beliefs, the notion that one must be responding to the commands of a particular religious organization to claim the protection of the Free Exercise Clause is rejected. The fact that Sunday work has become a way of life does not constitute a state interest sufficiently compelling to override a legitimate free exercise claim, since there is no evidence that there will be a mass movement away from Sunday employment if appellant succeeds on his claim. Frazee v. Illinois Department of Employment Security, 109 S.Ct. 1514 (1989). 6-58 Freedom of Religion Plaintiff, a Jehovah witness, was initially hired to work in his employer's roll foundry, but when the foundry was closed, he was transferred to a department that fabricated turrets for military tanks. Plaintiff asserted that his religious beliefs prevented him from participating in the production of weapons. His employer offered no other non-war production jobs. Plaintiff requested to be laid off, but when his request was denied, he quit. Plaintiff subsequently applied for but was denied unemployment compensation. Indiana state law requires applicants for unemployment compensation to show that they left work for a good cause in connection with the work. Issue: Is the denial a violation of the First Amendment? Held: Yes. When the state conditions receipt of an important benefit upon conduct proscribed by a religious belief, thereby putting substantial pressure on an adherent to modify his behavior and to violate his beliefs, a burden upon religion exists. The state may justify an inroad on religious liberty by showing that it is the least restrictive means of achieving some compelling state interest. However, only those interests of the highest order can overbalance legitimate claims to the free exercise of religion. The interests advanced by the state to avoid widespread unemployment and to avoid a detailed probing by employers into job applicants' religious beliefs do not justify the burden placed on free exercise of religion. Thomas v. Review Bd. of Indiana Employment Sec., 100 S.Ct. 1425 (1981). 6-59 Freedom of Religion California's imposition of its general 6 percent sales and use taxes on religious merchandise sold in the state by religious organizations does not violate the First Amendment. A generally applicable sales and use tax, which is not a flat license tax, which constitutes only a small part of the sale price, and which is applied neutrally without regard to the nature of the seller or purchaser, does not place an onerous burden on religious activity. Jimmy Swaggart Industries v. Board of Equalization of California, 110 S.Ct. 688 (1990). 6-60 Freedom of Religion When a state denies the receipt of a benefit because of conduct mandated by religious belief, a burden on the exercise of religion exists. Not only is it apparent that Hobbie's declared ineligibility for benefits derived solely from the practice of religion, but also the pressure on her to forego that practice (not working on her Sabbath) is unmistakable. The First Amendment protects the free exercise rights of employees who adopt religious beliefs or convert from one faith to another after they are hired. The timing of Hobbie's conversation is immaterial to our determination that her free exercise rights have been burdened. Hobbie v. Unemployment Appeals of Florida, 107 S.Ct. 1046 (1987). 6-61 Freedom of Religion A Connecticut statute which provided Sabbath observers with absolute and unqualified right not to work on their Sabbath, violated the establishment clause. It imposed on employers and employees an absolute duty to conform their business practices to a particular religious practice of the employee by enforcing observances of the Sabbath the employee unilaterally designated. Thornton v. Caldor, 105 S.Ct. 2914 (1985). 6-62 Freedom Of Press Generally, No Prior Restraints (Censorship) Not Absolute • (e.g. Obscenity, Defamation, National Security) 6-63 Freedom Of Speech Covers both verbal & written communications Symbolic Speech • (e.g. Picketing, Flag Burning) Commercial Speech • Historically Less Protected, but more protections since the 1970’s • Protects Corporations • Protects Listener & Speaker • Includes Freedom Of Information (FOIA) 6-64 Freedom Of Speech • A local ordinance in Forsyth County, Ga., required permit applicants to pay fees of as much as $1,000, based on the estimated police and administrative costs associated with their protests or marches. The Forsyth County ordinance violated the First Amendment because it gave officials considerable discretion to set permit fees based on how much opposition a demonstration is expected to stir up. Forsyth County v. Nationalist Movement, 112 S.Ct. 2395 (1992). 6-65 Freedom Of Speech • A St. Paul ordinance made it a crime to burn a cross or do other acts that can arouse "anger, alarm or resentment" on the basis of race, religion or gender. The law wrongly singled out for censorship the expression of particular ideas. However objectionable those ideas might be, "The First Amendment does not permit St. Paul to impose special prohibitions on those speakers who express views on disfavored subjects." R.A.V. v. St. Paul, 112 S.Ct. 2538 (1992). 6-66 Freedom Of Speech Overbreadth Doctrine • Overly broad restrictions usually prohibited • A Missouri statute that prohibits the display, rental, or sale to minors of video cassettes that appeal to a "morbid interest in violence," or that depict violence in a manner that is "patently offensive" by "contemporary adult community standards." (Video Software Dealers Association v. Webster, 773 F.Supp. 1275 (W.D. Mo. 1991). Unlike obscenity, violent expression is protected by the First Amendment. Therefore, any regulation must be justified by a compelling interest and narrowly tailored to achieve that interest. The legislature's failure to articulate precisely the type of violence it considers to be detrimental to minors makes it virtually impossible to determine if the statute is narrowly drawn to regulate only that expression. The words "morbid interest in violence" and "contemporaneous adult standards" do not express with clarity what the legislature was attempting to regulate. 6-67 Freedom Of Speech Overbreadth Doctrine • Overly broad restrictions usually prohibited • The University of Wisconsin's student conduct code calls for disciplining students who engage in discriminatory speech or other expressive conduct. The rule seeks to eliminate "racist or discriminatory comments, epithets or other expressive behavior directed at an individual" if such comments "demean" the race, sex, religion, or other attribute of an individual and create an "intimidating, hostile or demeaning environment." Speech can be regulated only if it threatens to incite an immediate breach of the peace. The trouble with the challenged rule is that it applies to many situations where a breach of the peace is unlikely to occur. Speech that creates an "intimidating" or "hostile" environment may tend to stifle rather than provoke immediate reaction. The UWM Post Inc. v. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System, 774 F.Supp. 1163 (E.D. Wis. 1991). 6-68 Freedom Of Speech Overbreadth Doctrine • Overly broad restrictions usually prohibited • The Los Angeles International Airport commissioners banned all "First Amendment activities" within the "central terminal area." The resolution was facially unconstitutional under First Amendment overbreadth doctrine, regardless of whether airport was considered a nonpublic forum, because no conceivable governmental interest could justify such an absolute prohibition of speech. Airport Com'rs of Los Angeles v. Jews for Jesus, 107 S.Ct. 2568 (1987). 6-69 Commercial Speech • SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES v. WESTERN MEDICAL CENTER, 122 S.Ct. 1497 (2002) • FACTS: The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997 allows drug compounding and allows the advertisement of such services. However, this law prohibits the advertising or any other promotional announcement that a specific compounded drug is available. Pharmacists, fearing their promotional materials related to drug compounds might be found to violate the FDAMA, sought a declaratory judgment that this law’s prohibition on advertising specific compounded drugs was unconstitutional. • ISSUE: Does the FDAMA unconstitutionally infringe upon the pharmacists’ right to engage in commercial speech? 6-70 Commercial Speech • SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES v. WESTERN MEDICAL CENTER, 122 S.Ct. 1497 (2002) • DECISION: Yes. The Supreme Court reviews the four tests established in Central Hudson. The compounding of drugs, as practiced by the pharmacists involved in this case, is a lawful activity. The government’s interests in limiting the availability of compound drugs, which are not thoroughly tested by the FDA, are significant and substantial. The ban on advertisement of specific compound drugs does directly relate to the government’s interest stated above. However, the Court discusses numerous examples how the FDA could meet its interest without resorting to a restriction on commercial advertisement. Since the FDA didn’t show why these less restrictive examples weren’t feasible, the Court affirms the lower courts’ decisions that the FDAMA violates the First Amendment’s Free Speech clause. 6-71 Commercial Speech • The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) seeks to prohibit the advertising of lotteries by radio and television stations in Louisiana since these ads may be heard or seen in neighboring Texas and Arkansas where lotteries are illegal. The Greater New Orleans Broadcasting Association seeks to have the FCC restrictions declared in violation of the First Amendment’s protection of commercial speech. Issue: Are the FCC restrictions sufficiently narrow in scope to meet constitutional requirements? Held: No. The Supreme Court reaffirms the four-step analysis announced in Central Hudson. The Court rejects the FCC’s argument that its restrictions on lottery advertising are sufficiently narrow. The advertiser and the listening/viewing public, not the government, should be allowed to assess the value of accurate and nonmisleading information about lawful conduct. Greater New Orleans Broadcasting Association, Inc. v. United States, 119 S.Ct. 1923 (1999). 6-72 Commercial Speech • The State of Rhode Island allows advertising of alcoholic beverages prices only in the stores where the alcohol is sold. State law bans such advertising “outside the licensed premises.” 44 Liquormart, Inc., a licensed retailer, ran a newspaper ad stating the low prices at which peanuts, potato chips, and Schweppes mixers were being offered, identifying various brands of packaged liquor, and including the word “WOW” in large letters next to pictures of vodka and rum bottles. As a result of this ad, the Rhode Island Liquor Control Administrator assessed 44 Liquormart a fine of $400. Liquormart paid the fine and sought a declaratory judgment in Federal District Court that the Rhode Island law prohibiting off-premise advertising was in violation of the First Amendment’s free speech protection. Issue: Is the Rhode Island limitation on alcohol pricing advertisements unconstitutional? Held: Yes. Rhode Island failed to produce credible evidence that its restriction on advertising of alcohol prices reduced consumption of alcohol. There are other, perhaps more effective, methods of regulating the use of alcohol. A ban on truthful, nonmisleading commercial speech is not supported under these facts. 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island, 116 S.Ct. 1495 (1996). 6-73 Commercial Speech • The Federal Alcohol Administration Act prohibits beer labels from displaying the alcohol content. Coors proposed to include such content on its label, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms refused to grant Coors's application for this label. Issue: Is this restriction a violation of Coors's First Amendment rights? Held: Yes. To regulate commercial speech that is truthful and not misleading, the government's interest must be substantial and directly related to the interest being sought. Here, the government's concern to limit "strength wars" between breweries is substantial; however, restricting the contents of the labels on beer cans will do little good when the breweries are allowed to advertise the alcohol content of their beer in other ways. Thus the label restrictions are in violation of the First Amendment. Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co., 63 U.S.L.W. 4319 (1995). 6-74 Due Process Due Process • Procedural- Proper Notice & Hearing • SubstantiveProperty/Rights Affected By Gov’t Action • 5th Amendment- Federal • 14th Amendment- Extended to State Local 6-75 Due Process 5th Amendment “no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” Due Process includes both Procedural and Substantive issues. 6-76 Due Process Procedural Due Process • Procedures depriving an individual of her rights must be fair and equitable. • Constitution requires adequate notice and a fair and impartial hearing before a disinterested magistrate. 6-77 Due Process Procedural Due Process • National Council of Resistance of Iran v. Albright, p.86 The U.S. policy for determining if a foreign entity is a foreign terrorist organization violates procedural due process of law. The U.S. did not provide the court with any interests that would support failure to provide notice and a hearing before designating an entity as a terrorist organization. In the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks, this case has taken on added importance. 6-78 Due Process Substantive Due Process • Focuses on the content or substance of legislation. • e.g. Laws limiting fundamental rights (speech, privacy, religion) must have a “compelling state interest.” • e.g. Laws limiting non-fundamental rights require only a “rational basis”. 6-79 Due Process Due Process requires that criminal statutes be clearly worded (so that they put an ordinary person on notice). • Chicago v. Morales, 527 U.S. 41, 1999. The Court finds The Court finds Chicago’s Gang Congregation (Anti-loitering) Ordinance which was passed to help control street-gang activity and thereby decrease the murder rate, unconstitutionally vague and gives the police officer too much discretion. Note: In Chicago v. Youkhana The Court found that the freedom to loiter for innocent purposes is part of the constitutionally protected liberty interest. 6-80 Due Process STATE FARM MUTUAL AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE COMPANY v. CAMPBELL, 123 S.Ct. 1513 (2003) FACTS: The Campbells had their car insured with State Farm. The Campbells were involved in a car accident and were sued. A State Farm representative told the Campbells that their insurance would protect them and that they did not need their own lawyer. The Campbells were found liable for an amount greater than their insurance coverage. The Campbells then sued State Farm claiming the company’s bad faith misrepresentations resulted in the Campbells’ damages. Using evidence that State Farm had been involved in similar claims throughout the United States, the Campbells won a jury verdict of $2.6 million in compensatory damages and $145 million in punitive damages. The trial judge reduced the compensatory damages to $1 million and the punitive damages to $25 million. Following appeals, the Utah Supreme Court reinstated the $145 million in punitive damages. State Farm asked the U.S. Supreme Court to declare that these punitive damages violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. 6-81 Due Process STATE FARM MUTUAL AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE COMPANY v. CAMPBELL, 123 S.Ct. 1513 (2003), p.164 ISSUE: In this factual situation, does the Due Process clause prohibit this level of punitive damages? DECISION: Yes. The U.S. Supreme Court reviews the principles established in BMW of North America, Inc. v. Gore. The Court expresses concern that the degree of reprehensibility of State Farm’s bad faith is unreasonably increased by the evidence from cases outside of Utah. In addressing a proper ratio of punitive damages to compensatory damages, the Court seems to want to limit such ratio to a single digit. In light of Utah’s civil sanction for State Farm’s bad faith being limited to $10,000, the Court finds the $145 million in punitive damages is unreasonable, arbitrary, and unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. 6-82 Due Process . Dr. Ira Gore purchased in Birmingham, Alabama, a new BMW automobile for $40,750.88. After nine months, Dr. Gore noticed that the paint was flawed. He was told by the proprietor of “Slick Finish” that his car had been repainted. Upon inquiring at the BMW dealership where he purchased the car, Dr. Gore was told that his car had been repainted prior to its sale. BMW acknowledged that it had a nationwide policy that if the cost of repairing damages done during manufacturing or transportation did not exceed 3% of the retail value, the car was sold as new. If such repairs exceeded the 3% figure, the car was used by the company for a period of time and then sold as a used vehicle. The actual cost of repairs to Dr. Gore’s car was $601.37. Since this was well below the 3% stated in BMW’s policy, the car was sold as new, and Dr. Gore was not informed of the repairs. Feeling that he had been defrauded, Dr. Gore filed a lawsuit against BMW. A jury awarded Dr. Gore $4,000 in compensatory damages and $4 million in punitive damages. BMW appealed the award of punitive damages and argued that this amount was constitutionally excessive. The Alabama Supreme Court reduced the punitive damages by half but upheld an award of $2,000,000. Issue: Is this award of punitive damages unconstitutional? Held: Yes, this award violates the due process clause. There are three standards that apply to ensure that a defendant is properly notified of the magnitude of a possible sanction. These standards include (a) a reasonable relationship between the potential punitive damages and the degree of reprehensibility of the defendant’s action; (b) an appropriate ratio between the punitive damages and the actual harm caused by the defendant; and (c) a reasonable comparison among the punitive damages awarded and comparable sanctions in similar cases. Under these standards, the Alabama courts’ award is unconstitutionally excessive. BMW of North America, Inc. v. Gore, 116 S.Ct. 1589 (1996). 6-83 Due Process An Oklahoma law required contract creditors of deceased persons to file claims within 2 months of the publication of a notice advising creditors of probate proceedings. Issue: Is this State action a denial of due process? Held: Yes. Creditors who are either known to the estate or whose identities are reasonably ascertainable are entitled by the Due Process Clause to receive notice by mail or other means certain to assure actual notice. The claim is a property interest and the probate procedures are state action. Tulsa Professional Collection Services v. Pope, 108 S.Ct. 1340 (1988). 6-84 Equal Protection Prohibits Arbitrary Discrimination Tests • Minimum Rationality Test – Rational connection to a permissible state purpose • Strict Scrutiny Test- Compelling State Purpose. Applies where a suspect class or fundamental right is involved. Generally applied in cases involving race, voting, etc. • Quasi-Strict Scrutiny Test –Substantially related to an important state purpose. Often applied in “gender” cases. • Note: Which test the court chooses to apply often determines the outcome of the case 6-85 Equal Protection Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union, p. 91 • The Supreme Court enjoined enforcement of the Child Online Protection Act. The statute, which was designed to shield minors from harmful speech, could not pass the strict scrutiny test. Specifically, the Court believed there to be less restrictive alternatives to the statute. Strict scrutiny places the burden on the government to demonstrate that its actions are furthering a compelling interest in a manner that intrudes on protected rights no more than is absolutely necessary. Compelling interests are objectives that are just as important as the fundamental rights that are abridged by a statute. First amendment rights are considered one of our most fundamental constitutional rights and are, therefore, accorded strict scrutiny. 6-86 Equal Protection Mainstream Marketing Services v. Federal Trade Commission, p.93 • Congress enacted a do-not-call registry that created a list of telephone numbers of people who do not wish to receive unsolicited calls from commercial telemarketers. The court upheld the registry, concluding that its restrictions on commercial speech passed the intermediate scrutiny test. Not only does the registry protect the privacy rights of individuals and protect against fraudulent and abusive calls, but it does not suppress and excessive amount of speech. Commercial speech is less protected than noncommercial speech. Talk them through the four-step test and contrast it with the strict scrutiny test used for restrictions on noncommercial speech. 6-87 Equal Protection • ADARAND CONSTRUCTORS, INC. v. PENA, 115 S.Ct. 2097 (1995) • FACTS: Mountain Gravel & Construction Company was awarded the prime contract for a highway construction project in Colorado. Mountain Gravel then solicited bids from subcontractors for the guardrail portion of the contract. Adarand, a Colorado-based highway construction company specializing in guardrail work, submitted the low bid. Gonzales Construction Company also submitted a bid. Mountain Gravel awarded the subcontract to Gonzales since Gonzales qualified as a minority contractor and Adarand did not. The prime contract’s terms provide that Mountain Gravel would receive additional compensation if it hired subcontractors certified as small businesses controlled by “socially and economically disadvantaged individuals.” After losing the guardrail subcontract to Gonzales, Adarand filed suit claiming that the race-based presumptions involved in the use of subcontracting compensation clauses violate Adarand’s right to equal protection. The District Court granted the Government’s motion for summary judgment. The Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit affirmed. • • ISSUE: What is the standard review when considering race-based actions by governmental units? 6-88 Equal Protection • ADARAND CONSTRUCTORS, INC. v. PENA, 115 S.Ct. 2097 (1995) • DECISION: Applies Strict scrutiny. The Court examined its various decisions addressing this issue, including Bakke (1978), Fullilove (1980), Wygant (1986), Croson (1989), and Metro Broadcasting (1990). To clarify the various holdings, this Court reached a majority opinion that all racial classifications, imposed by any level of government, must be analyzed by a reviewing court under strict scrutiny. 6-89 Equal Protection • The State of Iowa passed a law allowing slot machines to be placed on riverboats. The proceeds from these machines were taxed at the rate of 20%. Subsequently, Iowa permitted slot machines to be placed at race tracks. The proceeds from these machines were taxed at a rate as high as 36%. The race tracks owners filed suit arguing that the higher tax rate on their slot machines denied them the equal protection of laws. Issue: Does the existence of two tax rates on similar slot machines violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? Held: No. The Supreme Court holds that Iowa is regulating economic activities in this case. Therefore, the test of equal protection is based on minimal scrutiny. Since a rational basis can be found (such as not wanting to encourage as many slot machines at race tracks as on riverboats), the two tax rates are upheld. Fitzgerald v. Racing Association of Central Iowa, 123 S.Ct. 2156 (2003). 6-90 Equal Protection City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., Inc. 473 U.S. 432 (1985) Facts: Respondent Cleburne Living Center, Inc. (CLC), which anticipated leasing a certain building for the operation of a group home for the mentally retarded, was informed by petitioner city that a special use permit would be required, the city having concluded that the proposed group home should be classified as a “hospital for the feebleminded” under the zoning ordinance covering the area in which the proposed home would be located. Accordingly, CLC applied for a special use permit, but the City Council, after a public hearing, denied the permit. CLC and others (also respondents here) then filed suit against the city and a number of its officials, alleging that the zoning ordinance, on its face and as applied, violated the equal protection rights of CLC and its potential residents. 6-91 Equal Protection City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., Inc. 473 U.S. 432 (1985) Procedural History: The District Court held the ordinance and its application constitutional. The Court of Appeals reversed, holding that mental retardation is a “quasi-suspect” classification; that, under the applicable “heightened-scrutiny” equal protection test, the ordinance was facially invalid because it did not substantially further an important governmental purpose; and that the ordinance was also invalid as applied. Holding: 1. The Court of Appeals erred in holding mental retardation a quasi-suspect classification calling for a more exacting standard of judicial review than is normally accorded economic and social legislation. 2. Requiring a special use permit for the proposed group home here deprives respondents of the equal protection of the laws, and thus it is unnecessary to decide whether the ordinance’s permit requirement is facially invalid where the mentally retarded are involved. 6-92 Some Equal Protection Issues 1. Legislative 2. 3. 4. Apportionment Real EstateRacial Segregation Rights Of Legitimates & Illegitimates Jury Makeup 5. Voting 6. 7. 8. Requirements Welfare Residency Rights Of Aliens Property Tax To Finance Schools 6-93 Constitutional Interpretation Should the Constitution be interpreted according to its “plain meaning” or is the Constitution a “living” or “evolving” document whose meaning changes according to the times? 6-94 Constitutional Interpretation Its primary architect, James Madison, said that “(If) the sense in which the Constitution was accepted and ratified by the Nation … be not the guide in expounding it, there can be no security for a faithful exercise of its powers.” (The Writings of James Madison, ed. G. Hunt, p.191) 6-95 Constitutional Interpretation Former Harvard Law Professor and Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story said, “A constitution of government is addressed to the common sense of the people, and never was designed for trials of logical skill, or visionary speculation.” (Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, 3rd ed. (Boston, 1858)) 6-96