La legitimidad, pertenece a la teoría institucional

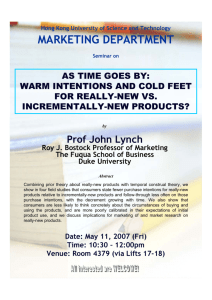

advertisement

XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 The Influence of the Electronic Service Encounter as a Determinant of the Relationships Between Perceived Benefits-Risks and Service Quality-Satisfaction-Loyalty Intentions Ramón Barrera Barrera rbarrera@us.es Universidad de Sevilla Antonio Navarro García anavarro@us.es Universidad de Sevilla José Manuel Ramirez Hurtado jmramhur@upo.es Universidad de Pablo de Olavide ABSTRACT In the context of electronic commerce B2C, two different service encounters can take place: 1) service encounters without incidents during which customers get the service for themselves and without the presence of employees and 2) service encounters with incidents with interpersonal and non-interpersonal interactions. Taking the traditional service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intention chain as a reference, in this work we analyze the effect of a Website’s service quality on the benefits and risks that online shoppers perceive and the effects of these benefits and risks on loyalty intentions, taking into account these two scenarios. Data collection was obtained from a convenience sample of online shoppers. We followed a quota sampling approach, with the intention of reproducing the sociodemographic profile of the population of Spanish online shoppers. The results obtained reflect that 1) the type of the service encounter has a moderating effect in these relationships. In this sense, the effects are stronger when incidents take place and are satisfactorily resolved; 2) the electronic service quality is a determinant of the online shoppers’ perceived benefits and risks; 3) regardless of the type of service encounter, reliability and recovery are the most important dimensions in the assessing of a Website’s service quality; 4) furthermore, consumers who have had no incident during the service encounter perceive a greater service quality, show higher levels of satisfaction and loyalty intentions toward the Website and perceive more benefits and less risks from online shopping than those who have had a problem during the service provision. KEY WORDS: electronic service quality, online shopping behavior, satisfaction, loyalty intentions. INTRODUCTION Internet has revolutionized commerce and business (e.g., Hoffman and Novak, 1996) and one of the most significant indicators of this transformation has been the adoption of the online retail channel. Specifically, 43% of the population of the EU 27 has purchased goods or services through the Internet (Eurostat, 2012). This volume of business generated by the XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 B2C e-commerce accounts for 14% of the total turnover of companies in these countries. In addition, 73% of households and 87% of companies in the EU 27 are connected to the Web (Eurostat, 2012). The face to face interpersonal interactions between sellers and customers has been replaced with technology-based Web interfaces. The management of these service encounters should be a priority for any organization with a presence on the Internet. This paper develops and tests a model that reflects the importance of service encounter in Internet shopping. Typically, online customers can more easily compare alternatives than offline customers and a competing offer is just a few clicks away on the Internet (Shankar et al., 2003). Add to that online consumers have a wider range of choices in selecting products and services, and highly competitive prices. As a result, competition between different Websites is high in order to attract the users’ attention and make them repeat a visit. In this situation, it is generally not easy for online retailers to gain competitive advantages based solely on a cost leadership strategy (Jun et al., 2004). Many researchers point out that to deliver a superior service quality is one of the key determinants of online retailers’ success (Zeithaml et al., 2002) and it is a major driving force on the route to long-term success (Fassnacht and Koese, 2006). This also involves a greater development of this electronic model and will also allow the online suppliers to differentiate themselves from the competition (Alt et al., 2010). To set out which aspects must be evaluated in the service quality, many researchers have used the service encounter approach (Bitner, 1990; Bitner et al., 1990; etc.). Shostack (1985: p.243) defines the term service encounter as “a period of time during which a consumer directly interacts with a service”. This definition encompasses all aspects of the service firm with which the consumer may interact, including its personnel, its physical facilities and other tangible elements, during a given period of time. Shostack (1985) does not limit the encounter to the interpersonal interactions between the customer and the firm. In fact, she suggests that service encounters can occur without any human interaction element. This view of a service encounter is still valid in the online services context. In the evaluation of e-service quality, it is necessary to consider all the cues and encounters that occur before, during and after the transactions (Zeithaml et al., 2002). Specifically, two different service encounters can take place in the context of Internet: (1) service encounters with non-interpersonal interactions, during which customers get the service for themselves, without the presence of employees (service encounter without incidents) and (2) service encounters with interpersonal and non-interpersonal interactions. Generally, the interactions with a member of the organization take place when a customer needs to solve any problem or doubt that may arise during the service delivery (service encounter with incidents). However, many works do not differentiate these two types of service encounter in the evaluation of the electronic service quality. In this sense, Parasuraman et al. (2005) criticize the work of Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2003), as the items of the customer attention dimension are answered by all the respondents instead of only by those who had problems or doubts. In other cases, the dimensions proposed to measure the electronic service quality does not consider how the problems or doubts are resolved when there are incidents in the service encounter (e.g., Aladwani and Palvia, 2002). On the other hand, in the literature about electronic services, most authors have limited themselves to studying the influence of the service quality (or its dimensions) on satisfaction and loyalty intentions. However, recent works have made it clear that other variables perform an important role in this chain. For example, Barrutia and Gilsanz (2012) propose a model in which the consumer knowledge-related resources are integrated into the e-service qualityvalue-satisfaction-behavior intentions chain. Ranaweera et al. (2004) suggest that the user XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 characteristics have a moderating effect on the relationship between Website satisfaction and consumer behavioral and attitudinal outcomes. Therefore, taking the traditional service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intention chain as a reference, in this work we analyze the effect of a Website’s service quality on the benefits and risks that online shoppers perceive and the effects of these benefits and risks on loyalty intentions. We do so taking into account the two scenarios previously differentiated. Moreover, we are going to analyze if the assessment of the perceived quality, the satisfaction with the purchase, the loyalty intentions toward a Website and the benefits and risks of online shopping perceived by the shoppers differ from one service encounter to another. To achieve the objectives proposed, the article is structured as follows. First, we review the most relevant research to help us identify the dimensions of e-service quality and the main online shopping benefits and risks. We describe the sample and measures used in the study. Then, we show the results of the empirical research. Finally, we discuss the conclusions and implications for management, the limitations and future research lines. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND The use of technology in service delivery The application of technology in services provisions also means the appearance of a new concept: electronic services. The contributions which have been made in the literature about the study of electronic services originate in the areas of marketing services (e.g., Janda et al., 2002), of electronic commerce (e.g., Yoo and Donthu, 2001), of research about information systems (e.g., Aladwani and Palvia, 2002) or in works which are centered on the technology acceptation model (TAM) (e.g., Davis 1989; Davis et al., 1989; etc.). Although there is not a commonly-accepted definition (Fassnacht and Koese, 2006), some have been proposed in the literature about the electronic services concept. For example, Rust (2001) defines the concept as “that service which is offered by an organization through an electronic system” (p. 283). Colby and Parasuraman (2003) suggest that “electronic services are services offered by an electronic means –normally Internet – and which refer to transactions begun and to a great extent controlled by the consumer” (p. 28). Fassnacht and Koese (2006) state that they are “those services that are offered using information and communication technologies in which the consumer only interacts with a user’s interface” (p.23). In these definitions two basic properties of electronic services stand out. Firstly, they are services which are offered through an electronic system–e.g., ATMs, telephonic banking, automatic billing in hotels through an interactive television, vending machines, etc. Secondly, electronic services are technological self-services or self-services based on technology (SSTs) (Dabholkar, 1996; Bitner et al., 2000; Dabholkar, 2000; Meuter et al., 2000). Customers begin and control the transaction performing active roles in the services provisions, in such a way that they are able to obtain the product or the service by themselves, even managing to get by without employees who attend the public. Nevertheless, some customers prefer interaction with employees, considering the service encounter as a social experience (Zeithaml and Gilly, 1987). The delivery of these electronic services offers benefits for both firms and customers. The use of technology enables the service provider to have a standardized service delivery, reduced labor costs, to expand the delivery options (Curran and Meuter, 2005) and to improve productivity and convenience for their employees and customers (La and Kandampully, 2002). However, the infusion of technology can also raise concerns of privacy, confidentiality and the receipt of unsolicited communications (Bitner et al., 2000). Some XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 studies have analyzed the factors that contribute to (or not) the use of an SST. For example, the ease of use and usefulness are critical constructs that influence an individual’s attitude toward a technology (Davis, 1989). Curran and Meuter (2005) propose four antecedents for attitudes toward the SSTs: ease of use, usefulness, risk and need for interaction. Dabholkar (1996) also found control and waiting time to be important determinants for using an SST. More recently, Belanche et al. (2011) suggest that the use of online services is determined by the perceived usefulness, the attitude toward its use and the perceived control. Consumers will weigh up these advantages and disadvantages when deciding whether or not to use an SST. For online shopping, their use will depend on the benefits and risks perceived by Internet users. Online shopping benefits and risks Different studies have identified two major types of behaviors which can be recognized as the motivations or benefits sought in Internet shopping (Hoffman and Novak, 1996; Hoffman and Novak, 1997; Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001): experiential or pleasure shopping and task or goal-oriented shopping. Experiential shopping responds to a more spontaneous and exploratory behavior in which the customer’s aspiration is to simply achieve positive shopping experiences, without any guiding beyond the desire to be entertained, the fun itself or to be immersed in this experience. The second type of behavior is the so-called task or goal-oriented shopping. In this type of behavior there are underlying functional motivations or the search for efficiency in the purchase. Unlike the previous consumer, this one uses the Internet as a means to carry out shopping for its convenience, prices, time saving, greater offer, etc. The literature suggests that, among the different factors valued by consumers when they purchase online, functional or utilitarian motivations prevail over those that are nonfunctional or hedonistic (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). In the literature, the main functional motivations which lead an Internet user to shop online are: 1) convenience, 2) the greater variety of products and services and 3) lower prices than in traditional establishments. Contrariwise, the most cited inconveniences were: 1) the fear of financial losses, 2) logistical problems and 3) not knowing how to do it. Convenience means a greater flexibility and time saving for the customer (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001; Zeithaml et al., 2000; Rohm and Swaminathan, 2004; Brengman et al., 2005). In this sense, online shopping can be done at any time of the day and 365 days a year so the customer is not limited to the shopping hours of traditional establishments. Furthermore, it can be done from any place which has an Internet connection. In this way, customers save time as they do not need to go the sales point. Secondly, Internet users state that in the Web they can find a greater variety of products and services and at better prices than in traditional establishments (Electronic Commerce Study B2C, 2012; Swinyard and Smith, 2003; Forsythe et al., 2006; Brengman et al., 2005). Occasionally, the Web is even the only means to find a product or a service. With respect to the inconveniences of online purchases, Internet users are concerned about suffering some kind of fraud (Allred et al., 2006; Forsythe et al., 2006; Brengman et al., 2005). In this sense, the main reasons that Internet users give for not making these purchases are: 1) insecurity and mistrusting the payment means, 2) fear of giving personal data and 3) mistrusting the provider (Electronic Commerce Study B2C, 2012). Secondly, online non- XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 shoppers compared to online shoppers consider that Internet shopping can cause logistical problems (Forsythe et al., 2006; Brengman et al., 2005; Swinyard and Smith, 2003). In this way, some people reject online shopping as they do not like to pay delivery costs, they think that it will be more difficult to return the product bought on Internet, they value the immediate possession of the purchase more, without having to wait for the mail delivery, they think that they can have trouble with the delivery, etc. Finally, some Internet users reject online shopping because they do not know how to do it or they have problems finding something in Internet (Swinyard and Smith, 2003; Forsythe et al., 2006; Allred et al., 2006). Measurement of electronic service quality Since the pioneering work of Zeithaml et al. (2002), the quality of online services has been explored in some depth. Parasuraman et al. (1985) suggest that service quality is an abstract and elusive construct because of three features that are unique to services: the intangibility, heterogeneity and inseparability of production and consumption. The best-known approach for measuring service quality is the SERVQUAL model (Parasuraman et al., 1988). The original five dimensions of SERVQUAL are tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. Some academic researchers have extended the SERVQUAL dimensions to the online context (Kaynama and Black, 2000; Sanchez-Franco and Villarejo-Ramos, 2004; Long and McMellon, 2004). However, traditional theories and concepts about service quality cannot be directly applied to the online context due to the important differences between the two settings. First, the service quality literature is dominated by people-delivered services, while in online services, human-to-human interactions are substituted by customer-toWebsite interactions (Parasuraman et al., 2005). Therefore, responsiveness and empathy dimensions can be evaluated only when the online customer contacts a member of the organization. Second, although reliability and security dimensions may be useful, tangibles are irrelevant as the customer only interacts with the Website. Third, new dimensions are relevant, such as Website design or information quality. Fourth, if the evaluation of the quality of a traditional service is going to depend especially on the personnel in charge of the service provision, the quality of the services which are offered through Internet are going to largely depend on the consumers themselves and their interaction with the Website (Fassnacht and Koese, 2006). Fifth, compared to the traditional quality of service, the eservice quality is an evaluation which is more cognitive than emotional (Zeithaml et al., 2000). In this way, these authors state that negative emotions such as annoyance and frustration are less strongly shown than in the quality of the traditional service, while positive feelings of affection or attachment which exist in traditional services do not appear in the Internet context. Various conclusions can be inferred from reviewing the literature: (1) the e-service quality is a multidimensional construct (Zeithaml et al., 2000) whose measurement must gather the evaluation of the interaction with the Website, the evaluation carried out by the customer of the product or service received and, if any problem arises, how the Website of the online firm handles it (Collier and Bienstock, 2006). Although most researchers are in favor of the evaluation of this latter aspect, Fassnacht and Koese (2006) state that we should not evaluate the human interaction which can take place in the electronic services provisions, given their self-service nature. (2) There are basically two approaches when tackling the conceptualization and measurement of e-service quality (Table 1). The epicenter of the first approach is the technical characteristics of the Website (technical quality). The first studies about Internet service quality belong to this first group. They centered uniquely on the interaction that takes place between the customer and the Website. None of this research XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 gathers all the aspects of the online purchasing process and therefore they do not carry out a complete evaluation of e-service quality. The main proposal of these measurement instruments is to generate information for the site designers, more than measuring the quality of the service which customers perceive (Parasuraman et al., 2005). This weakness is the main motive for the appearance of the second approach (service quality) which offers a more complete vision of the field of the e-service quality construct. The dimensions and the measurement instruments gather not only the technical aspects of the Website, but also how the customers perceive the quality of the product or service received and how their problems or doubts were solved during the service provision. (3) The researchers do not agree when identifying the dimensions of the quality of an electronic service. Moreover, the meaning, the importance and the items of the same dimension vary from one study to another. These differences are partly due to the scales being focused on one service in particular. (4) The evaluation of e-service quality is carried out at different levels of abstraction depending on the study. Most researchers offer a set of dimensions (first order constructs) and a series of indicators to measure each of them (e.g., Ho and Lee, 2007). However, other authors propose second order hierarchical models (e.g., Wolfibarger and Gilly, 2003), or even third order models (e.g., Fassnacht and Koese, 2006; O´Cass and Carlson, 2012). (5) Some authors propose scales in which problem solving does not appear (e.g., Liu et al., 2009) or is evaluated for the whole sample (e.g., Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). However, this last aspect must only be evaluated by those people who had problems during the transaction (Parasuraman e.g., 2005; Collier and Bienstock, 2006). Table 1. Online service quality scales in previous studies Focus: Technical quality Article Dimensions Aladwani and Palvia (2002) Appearance; specific content; content quality; technical adequacy Bressolles and Nantel (2008) Information; ease of use; site design; security/privacy Duque-Oliva and Rodríquez-Romero (2012) Efficiency; performance; privacy; system; variety Information and service quality; system use; playfulness; system design quality Adequacy of information; appearance; usability; privacy; security Ease of understanding; intuitive operation; information quality; interactivity; trust; response time; visual appeal; innovativeness; flow Liu and Arnett (2000) Liu, Du, and Tsai (2009) Loiacono, Watson, and Goodhue (2002) Ranganathan and Ganapathy (2002) Information content; design; security; privacy Sabiote, Frías, and Castañeda (2012) Ease of use; availability; efficacy; privacy; relevant information; Sanchez-Franco and Villarejo-Ramos (2004) Assurance; tangibles; reliability; empathy, ease of use, enjoyment; responsiveness Trocchia and Janda (2003) Performance; access; security; sensation; information Yoo and Donthu (2001) Ease of use; design; speed; security Focus: Electronic Service quality Article Barrutia and Gilsanz (2012) Bauer, Falk, and Hammerschmidt (2006) Collier and Bienstock (2006) Dimensions Process quality: efficiency; system availability; design; Information and Outcome quality Functionality / design; enjoyment; process; reliability; responsiveness Process dimension: functionality; information; accuracy; design; privacy; ease of use; Outcome dimension: order accuracy; order XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Fassnacht and Koese (2006) Ho and Lee (2007) Janda, Trocchia, and Gwinner (2002) Kaynama and Black (2000) O´Cass and Carlson (2012) Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Malhotra (2005) Rolland and Freeman (2010) condition; timeliness; Recovery dimension: interactive fairness; procedural fairness; outcome fairness Quality of the environment: graphics quality, clear presentation, quality of delivery: attractive assortment, quality of information, ease of use, technical quality, outcome quality: reliability, functional benefit; emotional benefit; Information quality; security; functionality; customer relationships; responsiveness Performance; access; security; sensation; information Content; accessibility, navigation, design and presentation; responsiveness; environment; customization e-Communication quality; e-Systems operation quality; eAesthetic quality; e-Exchange process quality E-S-QUAL: efficiency; system availability; fulfillment; privacy; E-RecS-QUAL: responsiveness; compensation; contact Ease of use; information content; fulfillment; reliability; security/privacy; post-purchase customer service Sheng and Liu (2010) Efficiency; fulfillment; system accessibility; privacy Sohail and Shaikh (2008) Efficiency and security; fulfillment; responsiveness Tsang, Lai, and Law (2010) Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2003) Yen and Lu (2008) Functionality; information quality and content; fulfillment and responsiveness; safety and security; appearance and presentation; customer relationship Design; fulfillment/reliability; privacy/security; customer service Efficiency; privacy; protection; contact; fulfillment Source: own elaboration If we set out from the conceptualization proposed by Collier and Bienstock (2006, p. 263), the domain of the service quality construct should gather the evaluation of the quality of the process of online interaction (technical aspects), the result of how the service or the product is delivered (result) and the way in which the service failures (if they occur) are managed (service recovery). The technical characteristics of the Website must consider: 1) the design (Yoo and Donthu, 2001), also called appearance (Aladwani and Palvia, 2002), the visual aspect (Loiacono et al., 2000), or aesthetics (Zeithaml et al., 2000); 2) the functionality (Collier and Bienstock, 2006), also called technical adequacy (Aladwani and Palvia, 2002), efficiency (Parasuraman et al., 2005) or ease of use (Janda et al., 2002); and 3) privacy (Collier and Bienstock, 2006) or the security that the Website offers (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). Secondly, the evaluation of the product or service delivery has been carried out with a single dimension generally called reliability (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003; Yang and Jun, 2002; Fassnacht and Koese, 2006) or performance (Janda, Trocchia and Gwinner, 2002; Parasuraman et al., 2005). Thirdly, if we take as a reference the works of Parasuraman et al. (2005) and Collier and Bienstock (2006), the evaluation of the quality of the e-service recovery responds to two aspects: the possibility of getting into touch with the firm (access or contact), and the effectiveness of problem solving (usually called response capacity). Following the literature review, the dimensions proposed to evaluate e-service quality are: design, functionality, privacy, reliability and recovery. These dimensions are herewith defined and explained. Design The design of a Website plays an important role in attracting, sustaining and retaining the interest of a customer in a site (Ranganathan and Ganapathy, 2002). Numerous studies in the literature consider the Website design as a dimension of e-service quality (Aladwani and Palvia. 2002; Loiacono et al., 2000; Yoo and Donthu, 2001; Liu et al., 2009; etc.). The XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 literature review about the key factors of a Website design highlights three important issues: attractiveness, proper fonts and proper colors. Although it has sometimes been regarded as a purely aesthetic element, prior studies have demonstrated the influence of Website design on site revisit intention (Yoo and Donthu, 2001), customer satisfaction (Tsang et al., 2010) and loyalty intentions (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). Functionality Functionality refers to the correct technical functioning of the Website. It is one of the most basic requirements for any kind of Website and its meaning is closely related to the dimensions of the system availability (Parasuraman et al., 2005), or technical adequacy (Aladwani and Palvia, 2002). The five items of functionality that we considered were: always up and available, has valid links, loads quickly, enables us to get on to it quickly and makes it easy and fast to get anywhere on the site. Its impact on online customers´ higher-order evaluations pertaining to Websites has also been observed. For example, Tsang et al. (2010) conducted an investigation in the travel online context in which the functionality was found to be the most important dimension in increasing customer satisfaction. Privacy Websites are usually collecting and storing large amounts of data concerning their users’ activities, user evaluations of online questionnaires or personal data (Tan et al., 2012). As a result, one of the aspects that most concern online consumers is the privacy of personal information (ONTSI, 2012). In our study, privacy refers to the degree to which the customer believes that the site is safe from intrusion and personal information is protected (Parasuraman et al., 2005; p. 219). The privacy of a Website should be reflected through symbols and messages to ensure the security of payment and the customer's personal information not being shared with other companies or Internet sites. As such, there appears to be a high degree of support for privacy as an important e-service quality dimension and it was found to be one of the most significant dimensions in increasing customer satisfaction (Janda et al., 2002). Reliability The evaluation of service delivered quality has been carried out with the dimensions of: fulfillment/reliability (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003), reliability (Yang and Jun, 2002), performance (Janda et al., 2002), fulfillment (Parasuraman et al., 2005), etc. Congruent with these articles, our study considers reliability as an important dimension of e-service quality. Moreover, in the context of online services, the information made available by the Websites is an important component of the service delivered. Therefore, reliability refers to the accuracy of the service delivered by the company, the billing process is correct and the information that appears on the Website is clear, current and complete. The service delivered quality or reliability has been empirically shown to have a strong impact on customer satisfaction and quality, and the second strongest predictor of loyalty intentions and attitude towards the Website (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). Recovery An essential aspect in the evaluation of the quality of an electronic service is the way in which the company solves problems or doubts which may arise during its provision. There is no doubt that errors in the electronic service provision cause the loss of customers in many XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 cases and a negative word of mouth. What is more, the physical separation between the customer and the supplier and the fact that customers can choose another company with a simple click accentuates even more the importance of solving these mistakes (Collier and Bienstock, 2006). Different dimensions have been proposed in the literature to evaluate this aspect: responsiveness (Zeithaml et al., 2000), customer attention (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003), communication (Cai and Jun, 2003), access (Yang and Jun, 2002), etc. In our study, service recovery refers to the customer’s capacity to communicate with the organization and how any problem or doubt that may arise is solved. Thus, the Website should show its street, e-mail, phone or fax numbers, the customer service must be available 24 hours a day/7days a week and the response to the customer´s inquiries must be quick and satisfactory. Moreover, this latter measure should only be evaluated by individuals who needed help or the solving of a problem. PROPOSED MODEL AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT Our model is based on the service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intention chain (Figure 1). The choice of a model and the hypotheses proposed must be made using a theoretical basis and supported by empirical results (Hair et al., 1999). Previous studies (e.g., Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Dabholkar et al., 2000; Cronin et al., 2000; Bagozzi, 1992; Oliver, 1997) give both theoretical and empirical reasons whi intentions relationship. In the electronic context, recent research also confirms the mediator effect of satisfaction (Carlson and O´Cass, 2010; Udo et al., 2010; Kassim and Abdullah, 2008; Chen and Kao, 2010; Yen and Lu, 2008; Collier and Bienstock, 2006; Gounaris et al., 2010). Other authors suggest that service quality has a direct effect on behavior intentions (e.g., Boulding et al., 1993; Parasuraman et al., 1988; 1991; Bloemer et al., 1999; Zeithaml et al., 1996). In the electronic services context, this effect is likewise confirmed (Parasuraman et al., 2005; Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). Therefore, we expect that: Hypothesis 1: the electronic service quality will have a positive effect on the consumer’s satisfaction. Hypothesis 2: the electronic satisfaction will have a positive effect on loyalty intentions. Hypothesis 3: the electronic service quality will have positive effect on loyalty intentions. Some authors suggest that the perceived benefits and risks in online purchases depend on the customer’s shopping experience and more specifically on the performance of the service offered by the Website (Forsythe et al., 2006). Hence, the better the online shopping experience, the greater the perceived benefits will be and the fewer the perceived risks will be. Therefore, we expect that: Hypothesis 4: the electronic service quality will have a positive effect on the online shopping benefits. Hypothesis 5: the electronic service quality will have a negative effect on the online shopping risks. Previous studies about adopting new technologies suggest that the perceived benefits and risks are antecedents of the use of a technology (Davis, 1989; Rogers, 1995). In the case of online shopping, Forsythe et al. (2006) suggest that its benefits and risks have an important role in the present behavior and in predicting the intention of continuing shopping in Internet. In this sense, these authors show that there is a positive (negative) correlation XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 between the perceived benefits (inconveniences) and future intentions of continuing shopping in the Internet. Therefore, we expect that: Hypothesis 6: the online shopping benefits will have a positive effect on loyalty intentions. Hypothesis 7: the online shopping risks will have a negative effect on loyalty intentions. FIGURE 1. Proposal model and hypotheses MEASUREMENT SCALES AND DATA COLLECTION Based on the previous research discussed above, we use five dimensions to evaluate electronic service quality: design, functionality, privacy, reliability and recovery. The first four dimensions are answered by all the respondents, while the recovery dimension is only evaluated by those people who had problems during the transaction (Parasuraman et al., 2005; Collier and Bienstock, 2006). The scales proposed are based on previous studies and the items aim to collect the full meaning of each dimension. To measure electronic satisfaction, we have used Oliver’s (1980) scale adapted to electronic services. The loyalty of intentions construct was measured with Zeithaml et al.’s (1996) loyalty behavior scale and reflects the repeat purchase and Website recommendation intentions. To measure the online shoppers’ perceived benefits and risks, we have used an adaptation of the scales proposed by Swinyard and Smith (2003) and Forsythe et al. (2006). We have chosen these research works because: 1) the procedures carried out to develop these scales guarantee their validity and 2) these scales have been used later in other relevant research. The survey instrument XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 contains 49 items and it is based on a 7-point Likert-type scale which ranges from strongly disagree to strongly agree (see Appendix). Data collection was obtained from a convenience sample of online shoppers. We surveyed purchasers who had already completed online transactions and who had sufficient online shopping experience. The respondents were asked to evaluate a particular Website of their choice, through which they had recently made a purchase. We followed a quota sampling approach, with the intention of reproducing the sociodemographic profile of the population of Spanish online shoppers. The respondents were able to access the Website where the online questionnaire was posted and they received a small incentive for participating. The field work took place from April to June 2012, and 915 questionnaires were received. 718 of them were valid questionnaires and 267 respondents said that they had a problem or doubt during the online service delivery (Table 2). The service failures or incidents are classified according the categories that appear in the B2C e-commerce Spanish survey: it has arrived damaged (35.8%), the delivery was done later than promised (30.6%), payment problems (18.6%), problems for return (13.7%), lack of information (8.4%) and problems downloading (6.8%). The research covered a wide range of websites, including a great variety of both tangible and intangible offerings. Table 2. Profile of the respondents and profile of the Spanish online shopper Online shopper (Sample) Gender Men Women n 400 318 % 55.7 44.3 Online shopper (B2C e-commerce Spanish Survey) % 52.6 47.4 Age 18-24 years old 25-34 years old 35-49 years old 50-64 years old 233 283 143 59 32.5 39.4 19.9 8.2 13.5 29.9 36.3 20.3 Level of education Primary education Secondary education University education 25 394 299 3.48 54.87 41.64 2.7 56.7 39.9 Population Less than 10,000 10,001-20,000 20,001-50,000 50,001-100,000 Over100,000 83 69 66 38 462 11.6 9.6 9.2 5.3 64.3 18.9 11.8 14.6 12.2 42.5 Social class Middle-Upper Middle Middle-Lower 150 511 57 20.89 71.17 7.94 40.2 37.5 22.3 Experience of Internet use More than three years Between one and three years Less than one year 664 42 12 92.48 5.85 1.67 80.8 8.9 5.1 Frequency of Internet use Everyday 424 59.05 71.9 XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 3 to 6 days per week One day per week or less 262 32 36.49 4.46 11.4 16.3 Note: Profile of the Spanish online shopper ‘B2C e-commerce Survey – ONTSI (2012). RESULTS Assessment of the Measurement Model To evaluate the scales proposed, we have followed the traditional procedures used in marketing research (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988). In Table 3 we present the results of dimensionality, convergent validity and reliability assessment. We also offer the standardized loadings, the composite reliability and the average variance extracted (AVE). As can be seen, all the items significantly load in their respective dimensions. The AVE values obtained are all above the recommended value of 0.50. This indicates that each construct’s items have convergent validity. What is more, each construct shows good internal consistency, with reliability coefficients which vary between 0.709 and 0.965. With respect to the importance of the e-service quality dimensions, reliability is the most important dimension in the assessment of a Website’s service quality, regardless of the type of service encounter. Moreover, in the service encounter without incidents, the second most important aspect of the service quality is how the organization solves the problems or doubts the customers had during the service provision. Table 3. Dimensionality, convergent validity, and reliability assessment First order factors Design DES1 DES2 DES3 Functionality FUN1 FUN2 FUN3 FUN4 FUN5 Privacy PRI1 PRI2 PRI3 Reliability REL1 REL2 REL3 REL4 REL5 Recovery REC1 REC2 REC3 REC4 REC5 REC6 REC7 Satisfaction SAT1 Service encounter without incidents (451 participants) SL CR AVE 0.804 0.577 0.772 0.733 0.774 0.876 0.640 0.677 0.801 0.84 0.869 Deleted 0.769 0.531 0.652 0.873 0.639 0.811 0.517 0.736 0.665 Deleted 0.681 0.79 0.945 0.816 0.741 Service encounter with incidents (267 participants) SL CR AVE 0.804 0.578 0.783 0.732 0.764 0.899 0.690 0.763 0.852 0.846 0.859 Deleted 0.803 0.578 0.699 0.859 0.712 0.824 0.540 0.806 0.729 Deleted 0.701 0.698 0.922 0.631 0.776 0.826 0.823 0.868 0.668 0.768 0.815 0.965 0.823 0.88 XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 SAT2 SAT3 SAT4 SAT5 SAT6 Loyalty intentions INT1 INT2 INT3 INT4 INT5 Convenience CON1 CON2 CON3 Variety and good prices OFE1 OFE2 Fear of financial losses FEA1 FEA2 FEA3 FEA4 Logistical problems PRO1 PRO2 PRO3 Don´t know how NOS1 NOS2 NOS3 Second order factors e-SQ e-SQDesign e-SQ Functionality e-SQPrivacy e-SQ Reliability e-SQRecovery Benefits BenefitsConvenience Benefits Variety and good prices Risks RisksFear of financial losses Risks Logistical problems Risks Don´t know how 0.802 0.86 0.885 0.886 0.911 0.912 0.924 0.905 0.909 0.911 0.921 0.700 0.745 0.749 0.876 0.929 0.869 0.836 0.718 Deleted 0.874 0.82 0.775 0.801 0.669 0.735 0.581 0.822 0.536 0.767 0.525 0.838 0.722 0.814 0.501 0.713 0.561 0.797 0.585 Deleted 0.85 0.784 0.709 0.550 0.79 0.69 0.777 0.747 0.826 0.544 0.736 0.841 0.668 0.695 0.737 0.799 0.698 0.69 0.738 0.502 0.803 0.598 0.679 0.799 0.712 0.656 0.746 0.602 Deleted 0.903 0.624 Deleted 0.803 0.894 0.768 0.521 0.538 0.597 0.590 0.932 - 0.522 0.599 0.608 0.901 0.755 0.768 0.630 0.923 0.862 0.640 0.616 0.802 0.899 0.778 0.577 0.945 0.842 0.852 0.902 0.919 0.883 0.582 0.995 0.719 0.497 Note: SL = standardized loadings; CR = Composite Reliability; AVE = Average Variance Extracted; All t-values were greater than 2.576 (p < 0.001). Discriminant validity, which verifies that each factor represents a separate dimension, was analyzed examining whether inter-factor correlations are less than the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 4 shows that the square roots of each AVE are greater than the off-diagonal elements. With this result, it should therefore be understood that there is discriminant validity in the e-service quality measurement scale. Table 4. Discriminant validity of measures XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Design Functionality Privacy Reliability Satisfaction Loyalty intentions Convenience Variety and good prices Fear Logistical Problems Design 0.731 Functionality 0.426 0.780 Privacy 0.371 0.369 0.733 Reliability 0.444 0.58 0.569 0.705 Satisfaction 0.396 0.393 0.454 0.681 0.861 Loyalty intentions 0.386 0.375 0.381 0.589 0.762 0.830 Convenience 0.206 0.235 0.168 0.291 0.223 0.216 0.857 Variety and goodprices 0.143 0.228 0.193 0.233 0.254 0.216 0.572 0.748 Fear -0.058 -0.098 -0.077 -0.055 -0.044 -0.004 -0.386 -0.196 0.736 Logistical Problems -0.019 -0.053 -0.048 -0.011 -0.01 -0.031 -0.28 -0.161 0.693 0.724 Don´t know how -0.102 -0.186 -0.13 -0.259 -0.152 -0.07 -0.455 -0.274 0.469 0.424 Don´t know how 0.781 Note: The bold numbers on the diagonal are the square root of the AVE. Off-diagonal elements are correlations between constructs. Assessment of the Structural Model As can be seen in Table confirmed in the two contexts. If we look at the structural coefficient value between the service quality and satisfaction with the online shopping, we can see that this coefficient is significant and positive for both types of service encounters. Specifically, when there are problems during the service provision, this coefficient is 0.858 (p<0.001), compared to 0.718 (p<0.001) in the case of there not having been any incident. Likewise, the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty intentions is greater when the service encounter takes place with incidents (0.745 compared to 0.620; p<0.001). However, the direct effect of the service quality on loyalty intentions is not significant. Therefore, hypotheses 1 and 2 are accepted and hypotheses 3 is rejected. Furthermore, the type of the service of the service encounter has a moderating effect in the service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intentions chain. In these sense, these relationships are stronger for the service encounter with incidents. On the other hand, the service quality positively influences the benefits of online shopping (0.431; p<0.001) and negatively influences the risks when the service encounter takes place without incidents (-0.131; p<0.05). In this way, when the customer perceives that the Website offers a high service quality, he/she positively values the benefits of online shopping and plays down its risks. In the case of the service encounter with incidents only the positive influence of the service quality on benefits is confirmed (0.427; p<0.001). These results lead us to accept hypotheses 4 and to partially accept hypotheses 5. However, in our study no statistically significant effect of the benefits or the risks of online shopping on loyalty intentions was observed. Therefore, hypotheses 6 and 7 are rejected. The values of the variance explained for the constructs of satisfaction and loyalty intentions are rather good. Nevertheless, the variance explained for the benefits and risks of online shopping are fairly low. To measure the model’s fit some indices supplied by the AMOS XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 statistical software were used. Values were recommended close to: 0.95 (CFI), 0.95 (TLI), 0.06 (RMSEA) and 0.08 (SRMR) (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Regarding the RMSEA index, there is also a confidence interval (LO90 and HI90), following the recommendation of Byrne (2009). In both contexts the model has a reasonably good fit of the data. Table 5. Structural models estimation H1: e-SQSatisfaction H2: SatisfactionLoyalty intentions Service encounter without incidents (451 participants) 0.718*** Service encounter with incidents (267 participants) 0.858*** 0.620*** 0.745*** 0.140 (n.s.) 0.132 (n.s.) H4: e-SQ Benefits 0.431*** 0.427*** H5: e-SQ Risks -0.131** -0.121 (n.s.) H6: BenefitsLoyalty intentions 0.031 (n.s.) 0.068 (n.s.) H7: RisksLoyalty intentions 0.048 (n.s.) 0.045 (n.s.) Satisfaction 0.516 0.736 Loyalty intentions 0.601 0.784 Benefits 0.177 0.182 Risks 0.017 0.015 χ2 2621.295 1844.470 Df 724 928 P 0 0 CFI 0.908 0.895 TLI 0.900 0.888 SRMR 0.061 0.0589 RMSEA 0.054 0.061 0.052-0.056 0.057-0.065 H3: e-SQ Loyalty intentions Variance explained (R2) Fit statistics LO90 and HI90 Note: **p<0.05; ***p<0.001; n.s.: not significant. Comparison of Means Next, we carried out the t-Student test and the Mann-Whitney test to analyze if the perceived quality assessment, the customers’ satisfaction, their loyalty intentions toward the Website and the perceived benefits and risks of online shopping differed according to the type of service encounter (Table 6). The results show that the mean scores of the e-service quality are significantly greater for the service encounter without incidents. Therefore, the consumers who did not have any problem or doubt during the service encounter have a significantly greater valuation of the Website’s service quality than those who had an incident during the service provision. Likewise, the satisfaction levels and the loyalty intentions are significantly higher for those consumers who did not have any problem. The consumers who did not have any incident give a greater score to the benefits of online shopping than those consumers who stated that they had an incident, although the differences are not statistically significant. Finally, those consumers who had an incident when shopping have significantly XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 greater difficulties doing this and perceive a higher risk of losing money than those who had no problem when shopping. Table 6. Student t-test and Mann-Whitney test Levene´s Test Mean (Enc. without incidents) Mean (Enc. with incidents) 4,882 5,369 4,967 5,707 5,822 5,323 4,720 5,045 4,707 5,261 5,249 4,919 4,919 4,854 3,898 4,575 2,751 e-SQ Design Functionality Privacy Reliability Satisfaction Loyalty intentions Benefits Convenience Variety /good prices Risks Fear Logistical Problems Don´t know how Note: **p<0.05 T-test Mann–Whitney Test Sig. T Sig. (2-tailed) 0,019 3,097 4,588 10,673 57,754 16,632 0,891 0,079 0,033** 0,001** 0,000** 0,000** -1,969 -3,563 - 0,049** 0,000** - 4,800 4,914 0,072 0,054 0,789 0,816 -1,028 0,584 0,304 0,559 4,194 4,581 3,163 0,168 0,363 10,899 0,682 0,547 0,001** 2,800 0,058 - 0,005** 0,954 - F Z Asym. Sig. (2-tailed) -2,526 -5,190 -4,981 -3,133 0,012** 0,000** 0,000** 0,002** -3,297 0,001** DISCUSSION Theoretical implications Numerous works in the literature show that an essential aspect for the success of B2C ecommerce is for consumers to perceive high quality services. This not only involves a greater development of this e-business model, it also allows firms to differentiate themselves from their competitors. In recent years, many researchers have analyzed the components or dimensions that shape the quality of the services offered through Internet. Furthermore, service quality has become the main way to achieve customer satisfaction and, therefore, their loyalty. In our study, the originality of the contribution lies in 1) integrating the benefits and risks which online shoppers perceive in the traditional service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intention chain and 2) analyzing these relationships in two contexts: service encounters without incidents versus service encounters with incidents. Next we show the main conclusions of our work. Firstly, our study confirms that the e-service quality has a direct effect on satisfaction and that the effect of satisfaction on loyalty intentions is important. Moreover, these relationships are statistically significant when the service encounter takes place with or without incidents. Theoretically, the mediator effect of satisfaction on the relationship is based on the model of Bagozzi (1992), in which the cognitive assessments (service quality) precede emotions (satisfaction with the service), and on the model of Oliver (1997), according to which the cognitive assessment of the service generates an affective or emotional response that leads to behavior or behavior intention. However, the direct effect of the service quality on loyalty intentions is not significant. This study therefore up holds that satisfaction mediates the effect of the service quality on loyalty intentions. Previous studies also empirically supported this mediator effect of satisfaction (e.g., Cronin et al., 2000; Dabholkar et al., 2000). However, this study’s first relevant contribution is that there are variables which can moderate these relationships. Specifically, the type of service encounter (with or without incidents) increases or diminishes the strength of these effects. In this sense, when errors occur during the electronic service provision, the measures carried out by the organization to solve these problems are an essential part of the assessment of the service XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 quality provided. Moreover, in these cases, if the customers’ problems or doubts are satisfactorily settled, the effects of service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intentions become stronger. The second interesting contribution of this work refers to the role of the online customers’ perceived benefits and risks in the service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intentions chain. In this sense, to offer a high e-service quality also means that the customers will positively value the benefits of Internet shopping and underestimate its risks. Nonetheless, a significant effect of the benefits and risks which online consumers perceived on loyalty intentions toward the Website where they shopped was not noted. This construct is basically determined by the satisfaction with the shopping experience on this Website. Thirdly, regardless of the type of service encounter, reliability is the most important dimension in the assessing of a Website’s service quality. These results coincide with the conclusions of previous studies, which also empirically demonstrated that reliability has a strong influence on the perceived quality of certain e-services (Bauer et al., 2005; Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). As a result, the managers of online services must center themselves specifically on questions such as the exactitude of the service offered and correct billing, and offer clear, complete and error-free information. However, in spite of there being a strong consensus about the fact that privacy is one of the most important in the evaluation of an online service quality (B2C-ONTSI study on e-commerce) and one of those that have the most influence on customer satisfaction (Janda et al., 2002), this research shows the slight importance of this dimension. This fact is possibly due to the technological advances of recent years concerning online purchase payment security (Udo et al., 2010) and there being a growing tendency in the number of customers who are familiar with this type of electronic transactions (B2C-ONTSI study on e-commerce). In our study, we ask the respondents to evaluate the Website which they use the most. Therefore, it seems that there is a certain familiarity and trust with the Websites chosen. In this line, previous studies point out that privacy may not be a critical factor in those who use Internet more often (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). For those users who do not carry out online purchases, privacy is probably not a factor of great importance. A third explanation may be the fact that younger consumers perceive fewer risks in this type of purchases than older consumers (Udo et al., 2010) (approximately 80% of our sample’s purchasers were between 18 and 34 years old). Fourthly, the consumers who have not had an incident during the service encounter perceive a better service quality, show greater levels of satisfaction and loyalty intentions toward the Website and perceive more benefits and less risks of online shopping than the consumers who had a problem during the service provision. Furthermore, these latter consumers have significantly lower skills in carrying out online purchases and perceive a higher risk of losing money Managerial implications From the management point of view, firstly, an essential aspect for the success of B2C ebusiness is for the online suppliers to know which aspects determined the quality of the services offered through Internet. During the first years of e-business, organizations paid more attention to the technical characteristics of the Website: design, functionality, privacy, etc. However, although these aspects are important, the customer’s evaluation of the product or service delivery and the way in which their problems or doubts have been resolved during the service provision must not be ignored by any organization. In this vein, the results of this XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 research show that the main aim for any online supplier must be to offer a reliable service for their customers to perceive high quality services and be satisfied. Reliability must be understood as the firm’s capacity to fulfill their commitments regarding e-service delivery or provision as agreed in the conditions. That is to say, the organization must offer exactly the service which the customer has contracted on the Website, the billing of this service must be carried out without mistakes, the packing of the products has to be secure, the products must be delivered to the customer on the date promised and their refund must be guaranteed. In the same way, the online suppliers must offer clear, detailed and error-free information about the products and services which appear in their Website. Another very important component of the quality of an e-service is how the consumer perceives that their problems or doubts are resolved by the organization. From the management point of view, online companies must identify the nature of these errors and start up service recovery programs and policies to attain their customers’ satisfaction and loyalty (Holloway and Beatty, 2003). When mistakes take place during the service provision, the online suppliers must make an effort to solve them or offer the consumer some kind of compensation, given that their satisfaction with the Internet shopping will be greater when no incident occurs and this will therefore increase their loyalty toward the Website. However, our study shows that the performance of the dimensions which make up the e-service quality and the satisfaction and loyalty levels is lower when these incidents exist. These results indicate that organizations often ignore aspects which are subsequent to the online shopping. This results in less customer satisfaction and loyalty. Online suppliers must offer different ways (email, telephone, etc.) for the consumer to be able to get in touch with the customer attention service. Moreover, these problems or doubts must not be resolved with a general response but a specific response to each customer’s problems. Although previous studies suggest that to get a lower price is not an important attribute for online shoppers (Bhatnagar and Ghose, 2004), in this study it was noted that online consumers very positively value the great variety of products and services which Internet offers and being able to find better prices than in traditional establishments, more than the convenience of online shopping. On the other hand, Bhatnagar and Ghose (2004) conclude that consumers are more concerned about the inconveniences of online shopping than about its benefits. However, this research shows that consumers value the benefits of Internet shopping more than its risks. According to Swinyard and Smith (2003), this research shows that fear of financial loss is one of the main concerns of Internet users when shopping on Internet. In any case, starting up strategies aimed at emphasizing the benefits of Internet shopping and reducing the risks perceived by the consumer will help the developing of electronic commerce. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH LINES Lastly, some limitations of this work must be recognized and certain future research lines proposed. The convenience samples do not allow the generalizing of the results to the rest of the population. Future studies must be carried out to try and validate and generalize the results of this study using a larger sample. Previous studies have analyzed the effect of eservice quality on the perceived value of online shopping (e.g., Bauer et al., 2006; Parasuraman et al., 2005). It would be interesting to analyze how the perceived value is integrated into the service quality-satisfaction-loyalty intentions chain. On the other hand, although utilitarian motives predominate in online shopping, it would be interesting in future research lines to analyze if those online shoppers whose motivation is mainly hedonistic XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 perceive a greater service quality, are more satisfied with the shopping and have a stronger loyalty toward a Website. Finally, the perception of the benefits and risks is changing over time (Forsythe et al., 2006). A longitudinal study could be proposed to observe how these perceptions change and what their causes are. REFERENCES Aladwani, A.M. and Palvia, P.C. (2002), “Developing and validating an instrument for measuring user-perceived Web quality”, Information and Management, Vol. 39, pp. 467476. Alt, R., Abramowicz, W. and Demirkan, H. (2010), “Service-orientation in electronic markets”, Electronic Markets, Vol. 20, pp. 177-180. Bagozzi, R.P. (1992), “The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions and behavior”, Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 55 No. 2, pp. 178-204. Barrutia, José M. and Ainhize Gilsanz, A. (2012), “Electronic Service Quality and Value: Do consumer knowledge-related resources matter?,” Journal of Service Research, DOI: 10.1177/1094670512468294. Bauer, H.H., Hammerschmidt, M. and Falk, T. (2005), “Measuring the quality of e-banking portals”, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 153-175. Belanche, D., Casaló, L.V. and Flavián, C. (2011), “Adopción de servicios públicos online: Un análisis a través de la integración”, Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 41-56. Bhatnagar, A. and Sanjoy Ghose (2004), “A Latent Class Segmentation Analysis of EShoppers,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 57, pp. 758-767. Bitner, M.J. (1990), “Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54 No. 2, pp. 69-82. Bitner, M.J., Booms, B.H. and Tetrault, M.S. (1990), “The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, pp. 71-84. Bitner, M.J., Brown, S.W. and Meuter, M.L. (2000), “Technology infusion in service encounters”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 138-149. Bloemer, J., de Ruyter, K. and Wetzels, M. (1999), “Linking perceived service quality and service loyalty: A multi-dimensional perspective”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 33 No. 11/12, pp. 1082- 1106. Boulding, W., Kalra, A., Staelin, R. and Zeithaml, V.A. (1993), “A dynamic process model of service quality: From expectations to behavioral intentions”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 30, pp. 7-27. Brengman, M., Geuens, M., Weijters, B., Smith, S.M. and Swinyard, W.R. (2005), “Segmenting Internet shoppers based on their Web-usage-related lifestyle: A crosscultural validation,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58 No. 1, pp. 79-88. Bressolles, G. and Nantel, J. (2008), “The measurement of electronic service quality: Improvements and application”, International Journal of E-Business Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 1-19. Brown, T.J., Churchill, G.A. and Peter, J.P. (1993), “Improving the measurement of service quality”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 69 No. 1, pp. 127-139. Byrne, B. (2009), “Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming”, (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis. Cai, S. and Jun, M. (2003), “Internet users’ perceptions of online service quality: A comparison of online buyers and information searchers”, Managing Service Quality, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 504-519. XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Carlson, J. and O´Cass, A. (2010), “Exploring the relationships between e-service quality, satisfaction, attitudes and behaviors in content-driven e-service Web sites”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 112-127. Chen, C. and Kao, Y. (2010), “Relationships between process quality, outcome quality, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for online travel agencies - evidence from Taiwan”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 30 No. 12, pp. 2081-2092. Colby, C. and Parasuraman, A. (2003), “Technology still matters”, Marketing Management, Vol. July/August, pp. 28-33. Collier, J.E. and Bienstock, C.C. (2006), “Measuring service quality in e-retailing”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 260-275. Cronin, J.J., Brady, M.K. and Hult, T.M. (2000), “Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 76 No. 2, pp. 193-218. Cronin, J.J. and Taylor, S.A. (1992), “Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 56, pp. 55-68. Curran, J.M. and Meuter, M.L. (2005), “Self-service technology adoption: Comparing three technologies”, The Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 103-113. Dabholkar, P.A. (1996), “Consumer evaluations of new technology-based self-service options: An investigation of alternative models”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 29-51. Dabholkar, P.A. (2000), “Technology in service delivery: Implications for self-service and service support”, In: T. A. Swartz and D. Iacobucci (eds) Handbook of Services Marketing (New York: Sage, pp. 103-110. Dabholkar, P.A., Shepherd, C.D. and Thorpe, D.I. (2000), “A compressive framework for service quality: An investigation of critical conceptual and measurement issues through a longitudinal study”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 76 No. 2, pp. 139-173. Davis, F. (1989), “Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 319-339. Davis, F., Bagozzi, R.P. and Warshaw, P.R. (1989), “User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models”, Management Science, Linthicum: August, Vol. 35 No. 8, pp. 982-1003. Duque-Oliva, E.J. and Rodríguez-Romero, C.A. (2012), “Perceived service quality in electronic commerce: An application”, Rev. Innovar, Vol. 21 No. 42, pp. 89-98. Eurostat (2012), “Information Society Statistics”, Available at http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Ecommerce_statistics. Fassnacht, M. and Koese, I. (2006), “Quality of electronic services: conceptualizing and testing a hierarchical model”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 19-37. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Forsythe, S., Liu, C., Shannon, D. and Gardner, L.G. (2006), “Development of a scale to measure the perceived benefits and risks of online shopping,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 55-75. Gerbing, D.W. and Anderson, J.C. (1988), “An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 25, pp. 186-192. Gounaris, S., Dimitriadis, S. and Stathakopoulos, V. (2010), “An examination of the effects of service quality and satisfaction on customers’ behavioral intentions in e-shopping”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 142-156. XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.R. and Black, W.C. (1999), “Multivariate data analysis”, London: Prentice Hall. Ho, C. and Lee, Y. (2007), “The development of an e-travel service quality scale”, Tourism Management, Vol. 28, pp. 1434-1449. Hoffman, D.L. and Novak, T.H. (1996), “Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60, pp. 50-68. Hoffman, D.L. and Novak, T.H. (1997), “A new marketing paradigm for electronic commerce”, Information Society, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 43-54. Holloway, B.B. and Beatty, S.E. (2003), “Service failure in online retailing: A recovery opportunity”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 92-105. Hu, Li-tze and Bentler, P.M. (1999), “Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives”, Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 6, pp. 1-55. Janda, S., Trocchia, P.J. and Gwinner, K.P. (2002), “Consumer perceptions of Internet retail service quality”, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 13 No. 5, pp. 412-431. Jun, M., Yang, Z. and Kim, D. (2004), “Customers’ perceptions of online retailing service quality and their satisfaction”, International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, Vol. 21 No. 8, pp. 817-840. Kaynama, S.A. and Black, C.I. (2000), “A proposal to assess the service quality of online travel agencies: An exploratory study”, Journal of Professional Services Marketing, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 63-88. Kim, E. and Lee, B. (2009), “E-service quality competition through personalization under consumer privacy concerns”, Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, Vol. 8, pp. 182-190. La, K. and Kandampully, J. (2002), “Electronic retailing and distribution of services: Cyber intermediaries that serve customers and service providers”, Managing Service Quality, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 100-116. Liu, C. and Arnett, K.P. (2000), “Exploring the factors associated with Web site success in the context of electronic commerce”, Information and Management, Vol. 38, pp. 23-33. Liu, C., Du, T.C. and Tsai, H. (2009), “A study of the service quality of general portals”, Information and Management, Vol. 46, pp. 52-56. Loiacono, E.T., Watson, R.T. and Goodhue, D.L. (2002), “Webqual: A measure of Website quality”, In K. Evans and Scheer (Eds.), Marketing Educators’ Conference: Marketing Theory and Application, pp. 433-437. Long, M. and McMellon, C. (2004), “Exploring the determinants of retail service quality on the Internet”, Journal of services marketing, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 78-90. Meuter, M.L., Ostrom, A.L., Roundtree, R.I. and Bitner, M.J. (2000), “Self-service technologies: Understanding customer satisfaction with technology-based service encounters”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 64 No. 3, pp. 50-64. Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información. B2C e-commerce Survey (2012), Available at http://www.red.es/notasprensa/articles/id/4878/conclusiones-del-informe-sobre-comercio-electronico-b2c2010-del-ontsi.html. O´Cass, A. and Carlson, J. (2012), “An empirical assessment of consumers’ evaluations of web site service quality: conceptualizing and testing a formative model”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 26 No. 6, pp. 419–434. Oliver, R.L. (1980), “A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 460-469. Oliver, R.L. (1997), “Effect of expectations and disconfirmation on post exposure product evaluations”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 62, pp. 480-486. XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry, L.L. (1985), “A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49, pp. 41-50. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry, L.L. (1988), “SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 64 No. 1, pp. 12-40. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry, L.L. (1991), “Understanding customer expectations of service”, Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 39-48. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Malhotra, A. (2005), “E-S-QUAL. A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 213-233. Ranaweera, C., McDougall, G. and Bansal, H. (2004), “A model of online customer behavior: moderating effects of customer characteristics, Business & Economics, January, pp. 1-18. Ranganathan, C. and Ganapathy, S. (2002), “Key dimensions of business-to-consumer Web sites”, Information and Management, Vol. 39, pp. 457-465. Rogers, E.M. (1995), “Diffusion of Innovations”, 4th Ed., The Free Press, New York, NY. Rohm, A.J. and Swaminathan, V. (2004), “A typology of online shoppers based on shopping motivations,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 57, pp. 748-757. Rolland, S. and Freeman, I. (2010), “A new measure of e-service quality in France”, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, Vol. 38 No. 7, pp. 497-517. Rust, R. (2001), “The rise of e-service”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 3, pp. 283-84. Sabiote, C.M., Frías, D.M. and Castañeda, J.A. (2012), “E-service quality as antecedent to esatisfaction. The moderating effect of culture”, Online Information Review, Vol. 36 No. 2, pp. 157-174. Sánchez-Franco, M.J. and Villarejo, A.F. (2004), “La calidad de servicio electrónico: Un análisis de los efectos moderadores del comportamiento de uso de la Web”, Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, Vol. 21, pp. 121-152. Shankar, V., Smith, A.K. and Rangaswamy, A. (2003), “Customer satisfaction and loyalty in online and offline environments”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 153-175. Sheng, T. and Liu, C. (2010), “An empirical study on the effect of e-service quality on online customer satisfaction and loyalty”, Nankai Business Review International, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 273-283. Shostack, G.L. (1985), “Planning the service encounter”, In Czepiel, J.A; Solomon, M.R. and Surprenant, C.F. (Eds). The Service Encounter, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA. Sohail, M.S. and Shaikh, N.M. (2008), “Internet banking and quality of service”, Online Information Review, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 58-72. Swinyard, William R. and Scott M. Smith (2003), “Why people (don´t) shop online: A lifestyle study of the Internet consumer,” Psychology & Management, Vol. 20 No. 7, pp. 567-597. Teas, R.K. (1993), “Expectations, performance evaluation, and consumers’ perceptions of quality”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 57, pp. 18-34. Trocchia, P.J. and Janda, S. (2003), “How do consumers evaluate Internet retail service quality?”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 243-253. Tsang, N.K., Lai, M.T. and Law, R. (2010), “Measuring e-service quality for online travel agencies”, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 306-323. Udo, G.J., Kallol, K. and Kirs, P.J. (2010), “An assessment of customers’ e-service quality perception, satisfaction and intention”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 30, pp. 481-492. Wolfinbarger, M. and Gilly, M. (2001), “Shopping online for freedom, control, and fun”, California Management Review, Vol. 43 No. 2, pp. 34-55. Wolfinbarger, M. and Gilly, M. (2003), “Etailq: Dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting e-tail quality”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 79 No. 3, pp. 183-198. XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Yang, Z. and Jun, M. (2002), “Consumer perceptions of e-service quality: From Internet purchaser and non-purchaser perspectives”, Journal of Business Strategies, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 19-41. Yen, C. and Lu, H. (2008), “Effects of e-service quality on loyalty intention: An empirical study in online auction”, Managing Service Quality, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 127-146. Yoo, B. and Donthu, N. (2001), “Developing a scale to measure the perceived quality of an Internet shopping site (SITEQUAL)”, Quarterly Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 31-46. Zeithaml, V.A. and Gilly, M. (1987), “Characteristics affecting the acceptance of retailing technologies: A comparison of elderly and nonelderly consumers”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 63 No. 1, pp. 49-68. Zeithaml, V., Berry, L.L. and Parasuraman, A. (1996), “The behavioral consequences of service quality”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60 No. 2, pp. 31-46. Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. and Malhotra, A. (2000), “A conceptual framework for understanding e-service quality: Implications for future research and managerial practice”, Working Paper, Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. and Malhotra, A. (2002), “Service quality delivery through Websites: A critical review of extant knowledge”, Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 362-375. APPENDIX Electronic service quality Design DES1: The Website looks attractive DIS2: The Website uses fonts properly DIS3: The Website uses colors properly Adapted from Liu et al. (2009) Functionality FUN1: This Website is always up and available FUN2: This Website has valid links FUN3: This Website loads quickly FUN4: This Website enables me to get on to it quickly FUN5: This Website makes it easy and fast to get anywhere on the site Adapted from Aladwani and Palvia (2002), Parasuraman et al. (2005) and Collier and Bienstock (2006) Privacy PRI1: In the Website appear symbols and messages that signal the site is secure PRI2: The Website assures me that personal information is protected PRI3: The Website assures me that personal information will not be shared with other parties Adapted from Janda et al. (2002), Collier and Bienstock (2006) and Parasuraman et al. (2005) Reliability REL1: The service received was exactly the same as what I ordered REL2: The billing process was done without mistakes REL3: Website information is clear REL4: Website information is current REL5: Website information is complete XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Adapted from Parasuraman et al. (2005), Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2003) and Aladwani and Palvia (2002) Recovery REC1: The Website shows its street, e-mail phone or fax numbers REC2: The Website has customer service representatives REC3: If I wanted to, I could easily contact a customer service representative REC4: The Website responds to my inquiries REC5: The Website gives me a satisfactory response REC6: When I have a problem the Website shows a sincere interest in solving it REC7: The website responds quickly to my inquiries Adapted from Collier and Bienstock (2006) and Parasuraman et al. (2005) Satisfaction SAT1: I am satisfied with my decision to purchase from this Website SAT2: If I had to purchase again, I would feel differently about buying from this Website SAT3: My choice to purchase from this Website was a wise one SAT4: I feel good regarding my decision to buy from this Website SAT5: I think I did the right thing by buying from this Website SAT6: I am happy that I purchased from this Website Adapted from Oliver (1980) Loyalty intentions INT1: I consider this Website to be my first choice to buy this kind of services INT2: I will do more business with the Website in the next few years INT3: I say positive things about the Website to other people INT4: I would recommend the Website to someone who seeks my advice INT5: I encourage friends and relatives to do business with the Website Adapted from Zeithaml et al. (1996) Online purchase benefits Convenience COM1: Online purchases are easy to do COM2: I like to buy on Internet as I can do it any time and any place COM3: I like to buy from home Variety /good prices OFE1: Internet offers products and services at better prices than traditional shops OFE2: I find a greater variety of products and services on Internet Risks of online purchasing Fear of financial losses MIE1: I don’t feel sure purchasing on Internet MIE2: I’m afraid of financial losses when I purchase on Internet MIE3: I don’t like to give my personal data if I buy online MIE4: I don’t trust companies which sell products on Internet Logistical problems PRO1: If I buy on Internet I can get product delivery problems PRO2: It’s complicated to return a product bought on Internet PRO3: It’s difficult to know the quality of products bought on Internet XXIX AEDEM Annual Meeting San Sebastián / Donostia 2015 Don’t know how NOS1: I don’t like to surf on Internet very much NOS2: It’s difficult for me to buy on Internet NOS3: It’s difficult for me to find what I want on Internet Adapted from Swinyard and Smith (2003) and Forsythe, Liu, Shannon and Gardner (2006) Note: All items are measured with a seven-point Likert scale, anchored at 1 “strongly disagree” and 7 “strongly agree”.