Phillis Wheatley Handout - Mounds Park Academy Blogs

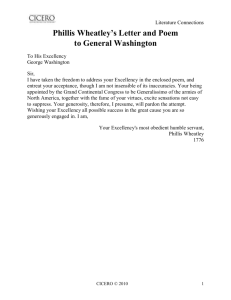

advertisement

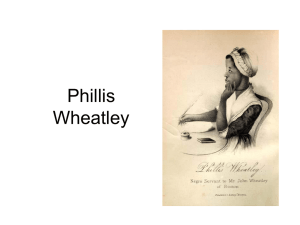

Phillis Wheatley 1753–1784 Although she was an African slave, Phillis Wheatley was one of the best-known poets in prenineteenth-century America. Pampered in the household of prominent Boston commercialist John Wheatley, lionized in New England and England, with presses in both places publishing her poems, and paraded before the new republic's political leadership and the old empire's aristocracy, Wheatley was the abolitionists' illustrative testimony that blacks could be both artistic and intellectual. Her name was a household word among literate colonists and her achievements a catalyst for the fledgling antislavery movement. Wheatley was seized from Senegal/Gambia, West Africa, when she was about seven years old. She was transported to the Boston docks with a shipment of "refugee" slaves, who because of age or physical frailty were unsuited for rigorous labor in the West Indian and Southern colonies, the first ports of call after the Atlantic crossing. In the month of August 1761, "in want of a domestic," Susanna Wheatley, wife of prominent Boston tailor John Wheatley, purchased "a slender, frail female child ... for a trifle" because the captain of the slave ship believed that the waif was terminally ill, and he wanted to gain at least a small profit before she died. A Wheatley relative later reported that the family surmised the girl—who was "of slender frame and evidently suffering from a change of climate," nearly naked, with "no other covering than a quantity of dirty carpet about her"—to be "about seven years old ... from the circumstances of shedding her front teeth." After discovering the girl's precociousness, the Wheatleys, including their son Nathaniel and their daughter Mary, did not entirely excuse Wheatley from her domestic duties but taught her to read and write. Soon she was immersed in the Bible, astronomy, geography, history, British literature (particularly John Milton and Alexander Pope), and the Greek and Latin classics of Vergil, Ovid, Terence, and Homer. In "To the University of Cambridge in New England" (probably the first poem she wrote but not published until 1773) Wheatley indicated that despite this exposure, rich and unusual for an American slave, her spirit yearned for the intellectual challenge of a more academic atmosphere. Although scholars had generally believed that An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield ... (1770) was Wheatley's first published poem, Carl Bridenbaugh revealed in 1969 that thirteen-year-old Wheatley—after hearing a miraculous saga of survival at sea—wrote "On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin," a poem which was published on 21 December 1767 in the Newport, Rhode Island, Mercury. But it was the Whitefield elegy that brought Wheatley national renown. Published as a broadside and a pamphlet in Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia, the poem was published with Ebenezer Pemberton's funeral sermon for Whitefield in London in 1771, bringing her international acclaim. By the time she was eighteen, Wheatley had gathered a collection of twenty-eight poems for which she, with the help of Mrs. Wheatley, ran advertisements for subscribers in Boston newspapers in February 1772. When the colonists were apparently unwilling to support literature by an African, she and the Wheatleys turned in frustration to London for a publisher. Wheatley had forwarded the Whitefield poem to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, to whom Whitefield had been chaplain. A wealthy supporter of evangelical and abolitionist causes, the countess instructed bookseller Archibald Bell to begin correspondence with Wheatley in preparation for the book. Wheatley, suffering from a chronic asthma condition and accompanied by Nathaniel, left for London on 8 May 1771. The now-celebrated poetess was welcomed by several dignitaries: abolitionists' patron the Earl of Dartmouth, poet and activist Baron George Lyttleton, Sir Brook Watson (soon to be the Lord Mayor of London), philanthropist John Thorton, and Benjamin Franklin. While Wheatley was recrossing the Atlantic to reach Mrs. Wheatley, who, at the summer's end, had become seriously ill, Bell was circulating the first edition of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), the first volume of poetry by an American Negro published in modern times. Poems on Various Subjects revealed that Wheatley's favorite poetic form was the couplet, both iambic pentameter and heroic. More than one-third of her canon is composed of elegies, poems on the deaths of noted persons, friends, or even strangers whose loved ones employed the poet. The poems that best demonstrate her abilities and are most often questioned by detractors are those that employ classical themes as well as techniques. In her epyllion "Niobe in Distress for Her Children Slain by Apollo, from Ovid's Metamorphoses , Book VI, and from a "View of the Painting of Mr. Richard Wilson," she not only translates Ovid but adds her own beautiful lines to extend the dramatic imagery. In "To Maecenas" she transforms Horace's ode into a celebration of Christ." In addition to classical and neoclassical techniques, Wheatley applied biblical symbolism to evangelize and to comment on slavery. For instance, "On Being Brought from Africa to America," the best-known Wheatley poem, chides the Great Awakening audience to remember that Africans must be included in the Christian stream: "Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain, /May be refin'd and join th' angelic train." The remainder of Wheatley's themes can be classified as celebrations of America. She was the first to applaud this nation as glorious "Columbia" and that in a letter to no less than the first president of the United States, George Washington, with whom she had corresponded and whom she was later privileged to meet. Her love of virgin America as well as her religious fervor is further suggested by the names of those colonial leaders who signed the attestation that appeared in some copies of Poems on Various Subjects to authenticate and support her work: Thomas Hutchinson, governor of Massachusetts; John Hancock; Andrew Oliver, lieutenant governor; James Bowdoin; and Reverend Mather Byles. Another fervent Wheatley supporter was Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Wheatley was manumitted some three months before Mrs. Wheatley died on 3 March 1774. Although many British editorials castigated the Wheatleys for keeping Wheatley in slavery while presenting her to London as the African genius, the family had provided an ambiguous haven for the poet. Wheatley was kept in a servant's place--a respectable arm's length from the Wheatleys' genteel circles--but she had experienced neither slavery's treacherous demands nor the harsh economic exclusions pervasive in a free-black existence. With the death of her benefactor, Wheatley slipped toward this tenuous life. Mary Wheatley and her father died in 1778; Nathaniel, who had married and moved to England, died in 1783. Throughout the lean years of the war and the following depression, the assault of these racial realities was more than her sickly body or aesthetic soul could withstand. On 1 April 1778, despite the skepticism and disapproval of some of her closest friends, Wheatley married John Peters, whom she had known for some five years. A free black, Peters evidently aspired to entrepreneurial and professional greatness. He is purported in various historical records to have called himself Dr. Peters, to have practiced law (perhaps as a free-lance advocate for hapless blacks), kept a grocery in Court Street, exchanged trade as a baker and a barber, and applied for a liquor license for a bar. Described by Merle A. Richmond as "a man of very handsome person and manners," who "wore a wig, carried a cane, and quite acted out 'the gentleman,'" Peters was also called "a remarkable specimen of his race, being a fluent writer, a ready speaker." Peters's ambitions cast him as "shiftless," arrogant, and proud in the eyes of some reporters, but as a black man in an era that valued only his brawn, Peters's business acumen was simply not salable. Like many others who scattered throughout the Northeast to avoid the fighting during the Revolutionary War, the Peterses moved temporarily from Boston to Wilmington, Massachusetts, shortly after their marriage. Merle A. Richmond points out that economic conditions in the colonies during and after the war were harsh, particularly for free blacks, who were unprepared to compete with whites in a stringent job market. These societal factors, rather than any refusal to work on Peters's part, were perhaps most responsible for the newfound poverty that Wheatley suffered in Wilmington and Boston, after they later returned there. Between 1779 and 1783, the couple may have had children (as many as three, though evidence of children is disputed), and Peters drifted further into penury, often leaving Wheatley to fend for herself by working as a charwoman while he dodged creditors and tried to find employment. During the first six weeks after their return to Boston, Wheatley stayed with one of Mrs. Wheatley's nieces in a bombed-out mansion that was converted to a day school after the war. Peters then moved them into an apartment in a rundown section of Boston, where other Wheatley relatives soon found Wheatley sick and destitute. As Margaretta Matilda Odell recalls, "She was herself suffering for want of attention, for many comforts, and that greatest of all comforts in sickness-cleanliness. She was reduced to a condition too loathsome to describe. ... In a filthy apartment, in an obscure part of the metropolis ... . The woman who had stood honored and respected in the presence of the wise and good ... was numbering the last hours of life in a state of the most abject misery, surrounded by all the emblems of a squalid poverty!" Yet throughout these lean years, Wheatley continued to write and publish her poems and to maintain, though on a much more limited scale, her international correspondence. She also felt that despite the poor economy, her American audience and certainly her evangelical friends would support a second volume of poetry. Between 30 October and 18 December 1779, with at least the partial motive of raising funds for her family, she ran six advertisements soliciting subscribers for "300 pages in Octavo," a volume "Dedicated to the Right Hon. Benjamin Franklin, Esq.: One of the Ambassadors of the United States at the Court of France," that would include thirty-three poems and thirteen letters. As with Poems on Various Subjects, however, the American populace would not support one of its most noted poets. (The first American edition of this book was not published until two years after her death.) During the year of her death (1784), she was able to publish, under the name Phillis Peters, a masterful sixtyfour-line poem in a pamphlet entitled Liberty and Peace , which hailed America as "Columbia"victorious over "Britannia Law." Proud of her nation's intense struggle for freedom that, to her, bespoke an eternal spiritual greatness, Wheatley ended the poem with a triumphant ring: Britannia owns her Independent Reign, Hibernia, Scotia, and the Realms of Spain; And Great Germania's ample Coast admires The generous Spirit that Columbia fires. Auspicious Heaven shall fill with fav'ring Gales, Where e'er Columbia spreads her swelling Sails: To every Realm shall Peace her Charms display, And Heavenly Freedom spread her gold Ray. On 2 January of that same year, she published An Elegy, Sacred to the Memory of that Great Divine, The Reverend and Learned Dr. Samuel Cooper, just a few days after the death of the Brattle Street church's pastor. And, sadly, in September the "Poetical Essays" section of The Boston Magazine carried "To Mr. and Mrs.________, on the Death of their Infant Son," which probably was a lamentation for the death of one of her own children and which certainly foreshadowed her death three months later." Phillis Wheatley died, uncared for and alone. As Richmond concludes, with ample evidence, when Wheatley expired on 5 December 1784, John Peters was incarcerated, "forced to relieve himself of debt by an imprisonment in the county jail." Their last surviving child died in time to be buried with his mother, and, as Odell recalled, "A grandniece of Phillis' benefactress, passing up Court Street, met the funeral of an adult and a child: a bystander informed her that they were bearing Phillis Wheatley to that silent mansion...." Recent scholarship shows that Wheatley wrote perhaps 145 poems (most of which would have been published if the encouragers she begged for had come forth to support the second volume), but this artistic heritage is now lost, probably abandoned during Peters's quest for subsistence after her death. Of the numerous letters she wrote to national and international political and religious leaders, some two dozen notes and letters are extant. As an exhibition of African intelligence, exploitable by members of the enlightenment movement, by evangelical Christians, and by other abolitionists, she was perhaps recognized even more in England and Europe than in America. Early twentieth-century critics of Black American literature were not very kind to Wheatley because of her supposed lack of concern about slavery. Wheatley, however, did have a statement to make about the institution of slavery, and she made it to the most influential segment of eighteenth-century society--the institutional church. Two of the greatest influences on Phillis Wheatley's thought and poetry were the Bible and eighteenth-century evangelical Christianity; but until fairly recently Wheatley's critics did not consider her use of biblical allusion nor its symbolic application as a statement against slavery. She often spoke in explicit biblical language designed to move church members to decisive action. For instance, these bold lines in her poetic eulogy to General David Wooster castigate patriots who confess Christianity yet oppress her people: But how presumptuous shall we hope to find Divine acceptance with the Almighty mind While yet o deed ungenerous they disgrace And hold in bondage Afric: blameless race Let virtue reign and then accord our prayers Be victory ours and generous freedom theirs. And in an outspoken letter to the Reverend Samson Occom, written after Wheatley was free and published repeatedly in Boston newspapers in 1774, she equates American slaveholding to that of pagan Egypt in ancient times: "Otherwise, perhaps, the Israelites had been less solicitous for their Freedom from Egyptian Slavery: I don't say they would have been contented without it, by no Means, for in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and by the Leave of our modern Egyptians I will assert that the same Principle lives in us." In the past ten years, Wheatley scholars have uncovered poems, letters, and more facts about her life and her association with eighteenth-century black abolitionists. They have also charted her notable use of classicism and have explicated the sociological intent of her biblical allusions. All this research and interpretation has proven Wheatley's disdain for the institution of slavery and her use of art to undermine its practice. Before the end of this century the full aesthetic, political, and religious implications of Wheatley's art and even more salient facts about her life and works will surely be known and celebrated by all who study the eighteenth century and by all who revere this woman, a most important poet in the American literary canon. — Sondra A. O'Neale, Emory University On Being Brought from Africa to America BY PHILLIS WHEATLEY 'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our sable race with scornful eye, "Their colour is a diabolic die." Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train. To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for North-America, &c. HAIL, happy day, when, smiling like the morn, Fair Freedom rose New-England to adorn: The northern clime beneath her genial ray, Dartmouth, congratulates thy blissful sway: Elate with hope her race no longer mourns, Each soul expands, each grateful bosom burns, While in thine hand with pleasure we behold The silken reins, and Freedom’s charms unfold. Long lost to realms beneath the northern skies She shines supreme, while hated faction dies: Soon as appear’d the Goddess long desir’d, Sick at the view, she languish’d and expir’d; Thus from the splendors of the morning light The owl in sadness seeks the caves of night. No more, America, in mournful strain Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain, No longer shalt thou dread the iron chain, Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand Had made, and with it meant t’ enslave the land. Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song, Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung, Whence flow these wishes for the common good, By feeling hearts alone best understood, I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat: What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast? Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d: Such, such my case. And can I then but pray Others may never feel tyrannic sway? For favours past, great Sir, our thanks are due, And thee we ask thy favours to renew, Since in thy pow’r, as in thy will before, To sooth the griefs, which thou did’st once deplore. May heav’nly grace the sacred sanction give To all thy works, and thou for ever live Not only on the wings of fleeting Fame, Though praise immortal crowns the patriot’s name, But to conduct to heav’ns refulgent fane, May fiery coursers sweep th’ ethereal plain, And bear thee upwards to that blest abode, Where, like the prophet, thou shalt find thy God. His Excellency General Washington by Phillis Wheatley Celestial choir! enthron'd in realms of light, Columbia's scenes of glorious toils I write. While freedom's cause her anxious breast alarms, She flashes dreadful in refulgent arms. See mother earth her offspring's fate bemoan, And nations gaze at scenes before unknown! See the bright beams of heaven's revolving light Involved in sorrows and the veil of night! The Goddess comes, she moves divinely fair, Olive and laurel binds Her golden hair: Wherever shines this native of the skies, Unnumber'd charms and recent graces rise. Muse! Bow propitious while my pen relates How pour her armies through a thousand gates, As when Eolus heaven's fair face deforms, Enwrapp'd in tempest and a night of storms; Astonish'd ocean feels the wild uproar, The refluent surges beat the sounding shore; Or think as leaves in Autumn's golden reign, Such, and so many, moves the warrior's train. In bright array they seek the work of war, Where high unfurl'd the ensign waves in air. Shall I to Washington their praise recite? Enough thou know'st them in the fields of fight. Thee, first in peace and honors—we demand The grace and glory of thy martial band. Fam'd for thy valour, for thy virtues more, Hear every tongue thy guardian aid implore! One century scarce perform'd its destined round, When Gallic powers Columbia's fury found; And so may you, whoever dares disgrace The land of freedom's heaven-defended race! Fix'd are the eyes of nations on the scales, For in their hopes Columbia's arm prevails. Anon Britannia droops the pensive head, While round increase the rising hills of dead. Ah! Cruel blindness to Columbia's state! Lament thy thirst of boundless power too late. Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side, Thy ev'ry action let the Goddess guide. A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine, With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine. - See more at: http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/22114#sthash.t0o2FT uj.dpuf