HEALTH IN GENERAL PLANS

AN EVALUATION OF SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY GENERAL PLANS

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Public Policy and Administration

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION

by

Lisbeth Maldonado

SPRING

2013

© 2013

Lisbeth Maldonado

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

HEALTH IN GENERAL PLANS

AN EVALUATION OF SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY GENERAL PLANS

A Thesis

by

Lisbeth Maldonado

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Mary Kirlin, D.P.A.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Peter M. Detwiler, M.A.

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Lisbeth Maldonado

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Department Chair ___________________

Robert Wassmer, Ph.D.

Date

Department of Public Policy and Administration

iv

Abstract

of

HEALTH IN GENERAL PLANS

AN EVALUATION OF SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY GENERAL PLANS

by

Lisbeth Maldonado

The rise of chronic health conditions in the San Joaquin Valley has increased the

focus on general plans as a tool to improve public health. General plans are the blueprints

for cities and counties as they guide the development of the physical environment. My

thesis evaluates the incorporation of public health goals into the general plans of the cities

and counties in the San Joaquin Valley.

I used a case study selection method and evaluation framework relying on the

American Planning Association (APA) Healthy Planning Report (2012) and the How to

Create and Implement Healthy General Plans Toolkit (2012). Because of my case study

selection method results, I surveyed the general plans of two counties and seven cities in

the San Joaquin Valley. I created a set of evaluation questions for seven health topic

categories and scored each general plan on its inclusion of health goals or policies.

I found that general plans in the San Joaquin Valley contain health topics that

affect the physical environment. I also discovered that cities and counties include these

topics throughout their general plans. Local general plans in the San Joaquin Valley

largely concentrate on planning for physical activity and transportation. They do not

v

include planning for nutrition opportunities as often as they discuss physical

development. However, the inclusion of health-related topics may increase as studies

connecting planning and health continue to link health outcomes with the built

environment. My evaluation found that small cities are planning for health within their

fiscal capacity and community needs.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Mary Kirlin, D.P.A.

_______________________

Date

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I feel blessed to have encountered people that have supported and

encouraged me to continue my education. First, I would like to thank my family for their

unconditional love and support. I would also like thank all the wonderful and amazing

people I have met here in Sacramento. You are my second family. Thank you for your

love and support.

I would like to thank Patricia, Alvaro, and Gabby Alvarado for opening their

home to me. Ana, Sulema, Adilene, Sergio, and Yeimi for your friendship and for the

many adventures and memories. In addition, I would like to thank Ms. Dana Grossi for

taking the time to read my drafts, and for all the many late night rides. Ana for all the

times you helped me move.

The Sacramento Friends Meeting and Ms. Carol for their financial support.

Jeannette Zanipatin for her mentorship, guidance, and friendship. Miguel Cordova for

his efforts to keep dreams alive. I promise to pay it forward! I want to express my

sincere gratitude to Professor Mary Kirlin and Professor Peter Detwiler for their patience

and guidance throughout this process.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ vii

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ x

List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... xi

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………….. 1

Purpose…..................................................................................................................... 1

Public Health in the San Joaquin Valley...................................................................... 2

The Local Planning Process ......................................................................................... 6

Planning and Health in the San Joaquin Valley ......................................................... 10

Organization of Thesis ............................................................................................... 12

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................................................. 13

Public Health and Planning........................................................................................ 13

Current Public Health and Planning Policy Efforts ................................................... 16

City Adoption of Health Promoting Policies ............................................................. 20

Implications from my Research ................................................................................. 24

3. METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................... 25

California General Plan Requirements ...................................................................... 26

Health in the General Plans of the San Joaquin Valley .............................................. 29

Analytical Framework ............................................................................................... 31

4. GENERAL PLAN EVALUATION RESULTS ............................................................... 38

Case Study Selection Results ..................................................................................... 38

Evaluation Results ..................................................................................................... 39

viii

Introduction and Access.............................................................................................. 40

Physical Activity ........................................................................................................ 42

Transportation ............................................................................................................. 45

Air and Water ............................................................................................................ 48

Food and Nutrition ..................................................................................................... 51

Mental Health and Social Capital .............................................................................. 59

Safety and Health Care Access .................................................................................. 57

Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 60

5. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................. 62

Summary .................................................................................................................... 62

Findings and Policy Implications................................................................................ 62

Limitations of Thesis ................................................................................................. 66

Future Research Opportunities................................................................................... 67

Appendix A. San Joaquin Valley County and City General Plan Availability ..................... 70

Appendix B. Case Study Evaluation Scores ......................................................................... 74

References ............................................................................................................................... 78

ix

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

1.

Page

Sample Health Elements and Integrated Health Language in California

General Plans………………………………………...……………………...…...7

2.

Office of Planning and Research General Plan Advisory Guidelines…………..27

3.

Advisory Health Topics Used to Model Evaluation Framework………………..33

4.

San Joaquin Valley Case Study Selection Criteria…….……………………......34

5.

Health Topics and Evaluation Questions...…….………………………………..37

6.

City and County Profiles……………………….……………………………….39

x

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

1.

Health in San Joaquin Valley General Plan Elements……………………...…. 30

2.

Introduction and Access………………………………………………………..40

3.

Physical Activity…………………………………………………………..…...43

4.

Transportation………………………….…………………...………..………...46

5.

Air and Water……………………………………………………………..…... 49

6.

Food and Nutrition…………………………………………………….……....52

7.

Mental Health and Social Capital……….…………………………………. ….55

8.

Safety and Health Care Access……………………………..………………….58

9.

Category Percentages………………………………………………………. …60

xi

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

In California, a general plan outlines and guides the future physical environment

of a city or county as it includes a vision of the area, goals, and policies. According to

the World Health Organization (2012), the health of the community and individuals is the

result of a variety of factors including the social environment, the economic environment,

the physical environment, and each person’s individual characteristics and behaviors.

The rise of chronic health conditions such as asthma, obesity, and diabetes has increased

the focus on the physical environment as a tool to improve public health. The general

plan guides planning in California and can be used as a vehicle to improve the safety and

condition of physical environments in areas with high chronic conditions. My thesis

examines how cities and counties in the San Joaquin Valley are incorporating public

health goals into their general plans

Purpose

The San Joaquin Valley is the lower portion of California’s Central Valley. The

region has a very diverse population, a mostly agricultural economy, air pollution, and

some of the highest rates of asthma, obesity, and diabetes in the nation. Local

governments can incorporate health into their general plans by adding health language to

the required elements in the general plan or by outlining health issues more directly in a

health element. The purpose of my thesis is to determine if local officials include public

2

health goals in their general plans. The rest of my introductory chapter will summarize

some of the major components of local government planning and introduce some of the

issues the San Joaquin Valley is currently facing. My literature review will follow and

my methodology will introduce my evaluation framework. I will use the How to Create

and Implement Healthy General Plans Toolkit (2012) health language recommendations

to create an analytical framework based on the American Planning Association’s (APA)

Healthy Planning Report (2012) evaluation framework.

Public Health in the San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley sits in the lower portion of California’s Central Valley. It

is composed of the Counties of San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Merced, Madera, Fresno, Kings,

Tulare, and Kern. The San Joaquin Valley’s unique geography and demographics make

it different from the rest of California and the Nation. Planning experts believe the San

Joaquin Valley “will be California’s greatest planning problem over the next 20 years”

(Fulton & Shigley, 2005, p. 35).

The population of the San Joaquin Valley has increased for two reasons: 1) more

people moving in from other areas of California for the cheaper housing and cost of

living, and 2) farm labor immigrants becoming permanent residents of the area. The

growth in population has increased urbanization pressures, and the development of

agricultural land (Fulton & Shigley, 2005). The region’s population spillover pressure is

3

concentrated in areas closer to the San Francisco Bay area and the Los Angeles area

(Teitz, Dietzel, & Fulton, 2005).

Immigrant workers are attracted to the year-round agricultural work that allows

farm workers to settle down in the area; they tend to be young and have low educational

levels. In 2003, San Joaquin Valley counties occupied six out of the seven spots on the

list of farm counties and produced about 60 percent of all crops statewide (Fulton &

Shigley, 2005, p. 35). A young population, low educational levels, and high poverty

characterize the social and economic structure of the San Joaquin Valley (Teitz, Dietzel,

& Fulton, 2005).

The high immigration levels have affected the population of the San Joaquin

Valley. Compared to California and the United States the region has a large Hispanic

population. At the county level, the racial segregation differences are not as apparent, but

census tract figures show that some counties have areas with a 90 percent Hispanic

population (Place Matters, 2012). In 2009, the population was 48.5 percent Hispanic,

38.2 percent White, 5.7 percent Asian, 4.5 percent Black, and 3.1 percent other (Place

Matters, 2012). During the same time, the area reported a much higher poverty rate

compared to California and the national average. More than one-fifth or 20.4 percent of

households reported incomes below the federal poverty level, compared to 14.2 percent

for California and 14.4 percent at the national level (Place Matters, 2012).

4

Air Quality and Water Access in the San Joaquin Valley

The bad air quality in the San Joaquin Valley is a contributing factor to respiratory

health problems in the region. The California legislature has passed three bills within the

last ten years targeting air quality. In 2003, The California Legislature approved AB 170

(Reyes, 2003) the Air Quality Element bill that requires each city and county within the

San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District jurisdiction to include air quality

standards in their general plans. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, AB 32,

(Pavley, 2006) requires a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. In 2008, the

Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008, also known as SB 375

(Steinberg, 2008) became law and requires the California Resources Board (CARB) to

set greenhouse gas emission targets for local governments. The policy targets the

reduction of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by vehicles and trucks and coordinates those

goals using the local planning process.

According to the EPA Strategic Plan (2011) trucks are one of the largest sources

of air pollution in the San Joaquin Valley. The strategic plan includes plans to reduce air

pollution concentrations by seven percent through regulatory actions. In addition, the

plan also include a campaign to create partnerships with businesses that will increase the

use of electric trucks in the region and educate diesel truck drivers to decrease the idling

of diesel trucks.

According to the Place Matters Report (2012), Tulare County has the highest

toxic air problems and a high rate of people living below 150 percent of the federal

5

poverty threshold. Areas of San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Fresno, and Tulare have the highest

percentage of Hispanics at an elevated respiratory risk. The American Lung Association

State of the Air Report (2012) ranked the following San Joaquin Valley areas in the top

25 nationwide as having high year round particle pollution:

1. Bakersfield-Delano

2. Hanford-Corcoran

3. Visalia-Porterville

4. Fresno-Madera

5. Modesto (short term particle pollution)

6. Merced (short term particle pollution)

7. Stockton (short term particle pollution)

The EPA reports that, just like air pollution, water pollution poses health risks for

San Joaquin Valley residents. Agriculture depends on water that comes from the BayDelta and San Joaquin River, and residents of the Valley mostly consume ground water

(EPA SVJ Strategic Plan, 2011). The EPA (2011) reports that out of 2,354 community

water systems that serve communities with populations with 3,300 or fewer people, 568

reside in the San Joaquin Valley, and 25 percent of those violate one or more drinking

water standards compared to only 10 percent statewide. Some of the chemicals found in

the water are arsenic and nitrate. Pesticide use in agriculture also contributes to the

pollution of the ground water. In addition, the use of pesticides in crops affects the

health of farm workers through skin contact, ingestion, or inhalation.

6

Asthma and Obesity

Residents of the San Joaquin Valley have similar life expectancies compared to

California and the United States. However, there are about 460 premature deaths

attributed to air pollution with an economic cost of $3 billion per year (Place Matters,

2012). Children in the San Joaquin Valley have asthma at a rate of one in six before the

age of 18 (Place Matters, 2012). A ten-year study of the area found that from 2003 to

2009 the rate of obesity increased from 26 percent in 2001 to 32 percent in 2009 among

adults failing to meet the target of 15 percent obesity rate for the area (Lee, 2012).

Among adolescents, the rate decreased from 15 percent to 10 percent, but still failed to

meet the target goal for the area of five percent (LEE, 2012).

The Local Planning Process

The local planning process involves various agencies and a variety of policies. .

In this section, I will summarize the major local planning requirements and include a

brief explanation of the various agencies and their responsibilities. I will be referring to

these terms throughout my thesis. All cities and counties must create a general plan and

zoning ordinance.

General Plans

The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) is responsible for

updating advisory general plan guidelines, monitoring general plan implementation, and

granting general plan extensions. The current general plan guidelines require seven

7

elements: land use, circulation, housing, conservation, open space, noise, and safety

(OPR, 2003). Cities and counties must update the housing element every five years, but

all other elements can be updated according to their own long range planning schedule.

Health is not a required element, but local governments are incorporating health into their

existing general plan elements or adding health as an additional element. OPR will be

updating the general plan guidelines in 2013 and are considering including health

guidelines. The following chart presents various cities in California that have adopted a

health element or have integrated health goals and policies as part of their general plan

language:

Table 1: Sample Health Elements and Health Language in California General Plans

City/County

Name

Anderson

General Plan

Element/Integrated Language

Health & Safety Element (2007)

Policy Descriptions

Physical activity, mixed use, transit

orientated and infill development.

Healthy Chino Element (2008)

Physical activity, walkability, nutrition,

Chino

public safety, and civic participation.

Community Wellness and Health Walkability, healthy food standards, parks

Richmond

Element (2008)

and open space.

Health Element (2011)

Transportation, healthy food access and

San Pablo

equity, access to services, and health and

safety.

Integrated Language (2008)

Public transportation, mixed use, and

Sacramento

transit oriented development.

Integrated Language (2004)

walkability, street connectivity, mixed use

Azusa

development, and the built environment.

Integrated Language (2005)

Walkabililty, healthy foods, pedestrian and

Chula Vista

bicycle safety and job housing balance.

Integrated Language (2003)

Walkability, mixed use development and

Paso Robles

development along transportation corridor.

Integrated Language(2006)

Healthy food access, public transportation

Watsonville

on grocery store routes and supporting local

organizations.

Note. Modeled after www.healthcitiescampaign.org/general_plan.html. Information confirmed

through a search of city websites and google search engine.

8

Cities and counties are each responsible for creating a general plan. Each

jurisdiction’s legislative body is responsible for creating the process to carry out a general

plan. Cities and counties can have planning departments and commissions that process

projects and evaluate how well they comply with their general plan requirements. These

planning bodies can create zoning plans, subdivisions regulations, and other ordinances

necessary to carry out the general plan. Depending on the city, the powers sometimes

rest with their legislative body.

Zoning

The zoning plan is a map that shows what type of allowable uses the city permits

in the area. For example, a plan can designate areas as residential, commercial, or open

land. There are different types of zoning ordinances and plans a city can include. The

first exclusive zoning allows only for one type of use per zone, separating industrial,

commercial, single family, and multifamily residential areas (Fulton & Shigley, 2005, p.

56). Due to the large lot requirements, this type of zoning is unfavorable because it

creates urban sprawl.

Mixed-use zoning is more flexible, as it allows housing and business to co-exist.

For example, old office buildings can become affordable housing. New buildings can

have retail shops at the ground level and housing or office space above.

Impact/performance zoning looks at how a building fits with the rest of the neighborhood

and whether its use will have any negative impact. For example, if the building includes

plans for a business that will need parking, the building will have to include a parking

plan (Fulton & Shigley, 2005, p.131).

9

A new zoning approach is form-based code zoning that does not focus on the use

of the buildings, but instead focuses on their design and how they fit with the

neighborhoods. Form-based codes usually separate use standards such as parking, but

planning professionals believe form-based codes should factor in neighborhood or district

level codes that include impact/performance zoning standards (Fulton & Shigley, 2005, p.

314).

Local governments have the power to approve local ordinances that either restrict

or allow certain land uses and they have the power to regulate urban sprawl. The

Subdivision Map Act gives local governments the ability to regulate new subdivisions

§66410. The Community Redevelopment law is part of the Health & Safety Code and

allows local governments to redevelop blighted areas §33000. However, California

budget problems caused the elimination of redevelopment agencies in 2012. Other major

planning considerations are included in the following section.

CEQA

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) establishes a system of

environmental reviews for development projects in California §21000. General Plans

also go through an Environmental Impact Review (EIR) before their local governments

approve them.

LAFCO

The local agency formation commission (LAFCO) is a special countywide agency

that processes all annexations, incorporations, and boundary changes. The Cortese-

10

Knox-Hertzberg Local Government Reorganization Act governs LAFCO rules (Fulton &

Shigley, 2005, p.69).

COG

Council of Governments (COGs) are regional agencies that administer federal

grants, focus on regional transportation, and work to find solutions on regional issues.

COGs are the agencies in charge of allocating regional housing numbers to comply with

housing element requirements of city and county general plans within their region (Teitz,

Dietzell, & Fulton 2005).

Local governments have control over what happens in the physical environment

under their jurisdictions. They can use a variety of planning tools to create healthy

environments. These tools evolve as new planning concepts emerge and are merging

with older processes.

Environmental Justice

The 2003 General Plan Guidelines included Environmental Justice (EJ) guidance

for the first time. In 1999, SB 115 (Solis, 1999) required OPR to guide cities and

counties in the incorporation of Environmental Justice language into their general plans

and made OPR the coordinating agency for related programs. The General Plan

Guidelines (2003) connects Environmental Justice to sustainable development at a local

level and to “smart growth” at the regional level. OPR’s 2003 guidelines refer to

sustainable development as promoting the three E’s: Environment, Economy, and Equity.

The Environmental Justice recommendations focus on topics such as infill development,

transportation, open space conservation, promoting mixed income, promoting energy

11

efficiency, and jobs/housing balance. Some of these topics cover many of the planning

goals that can help promote public health as the movement to promote public health

awareness in low-income regions and focus on present health issues has roots in the

Environmental Justice movement.

Planning and Health in the San Joaquin Valley

There is not enough research on planning trends and changes in the San Joaquin

Valley. The region is geographically diverse, as it is composed of agricultural land, rural

towns, suburban areas, and cities. However, OPR for the very first time included healthrelated questions in its Annual Survey (2012). One of the questions asked planning

officials if health is included in their jurisdiction’s general plan. Out of the 462 cities and

counties that responded to the question, 50 cities are located in the San Joaquin Valley.

Only Tulare County, Stanislaus County, San Joaquin County, Kings County, and Kern

County answered the question. Eleven cities in the San Joaquin Valley indicated that

health can be found in their circulation element, eight in their conservation element, four

in their housing element, 17 in their land use element, eight in their open space element,

and 15 indicated their jurisdiction does not have any such policies. Only two cities

indicated they had a health element; the largest number, 18 cities, indicated health is

included in their safety element (OPR Annual Survey, 2012).

12

Organization of Thesis

This thesis is a qualitative study that uses existing studies and toolkits available to

create an evaluative framework to analyze general plans in the San Joaquin Valley. In

this section, I summarize the remaining chapters and conclusion.

In my Literature Review, chapter 2, I summarize the background and history of

health and planning. Second, I outline the existing toolkits and literature related to the

inclusion of health topics in planning. Then, I collate literature related to current health

and planning topics.

Chapter 3 presents my analytical framework. I first summarize the California

general plan requirements and relevant policies, as they are the parameters that cities and

counties are working with to create their general plans. Lastly, I present my research

methodology, and evaluation questions.

Chapter 4 includes my San Joaquin Valley general plan evaluation results. I first

present the cities and counties that I selected using the evaluative framework. Afterward,

I present the results of my scoring on my evaluation health topics.

Lastly, in Chapter 5 I discuss my results and implications and conclude with

suggestions for further research

13

Chapter 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

The body of literature on local planning and health is limited but growing. The

purpose of my literature review is to find how public health goals and issues are

becoming part of local government planning policies. I searched for articles and studies

using Google Scholar, the EBSCO database, Proquest database, Lexis Nexis database,

and journals available through the Sacramento State library. I narrowed my search to

articles published within the last ten years. The relevant literature found guides my

methodology and research questions. I only located a few articles related to health topics

and the San Joaquin Valley. The articles show increased interest in the region and guide

my methodology. I first examine the roots of public health and planning. I then discuss

how planning and public health are interconnecting now. I include a discussion of the

various toolkits available that guide officials and advocates in creating health promoting

general plans. Lastly, I analyze city adoption of health promoting policies.

Public Health and Planning

Historically, health was one of the main driving forces of planning in the United

States. During the Industrial Revolution, planners concerned over the spread of disease

used states’ regulatory power to address sewer problems, clean water, and poor living

conditions. One of the first acts to address health and planning was the New York City

House Tenement Act of 1901. The act was part of a series of acts that set specific

14

building codes to protect people by requiring windows and fire escapes (Frank & Kavage,

2008).

New York implemented many land use regulations, but one of the oldest cases

regulating health is the 1867 California Supreme Court case of Shrader vs. San Francisco.

The City of San Francisco had banned slaughterhouses, as authorized by the State of

California in 1862, from certain areas of the city. The State authorized San Francisco to

“make regulations necessary for the preservation of the public health and the prevention

of contagious diseases,” (Fulton & Shigley, 2005, p 41). During this period, Public

Health had a strong influence in municipal politics with city governments operating under

two law maxims: salus populi suprema lex est (the welfare of the people is the supreme

law), and sic utere, tuo ut alienum non laedas (use your own as to not injure another)

(Robichaud, 2010).

At the start of the 20th century, planning focused on land use challenges of cities

and towns. Zoning became a popular planning tool by the early 1900s, and after the 1926

Supreme Court case of Euclid v. Ambler Realty, it became constitutional. Zoning is cited

as one of the tools that can be used to manage health, as one of its main purposes from its

inception was to separate industrial areas of towns from housing areas (Fulton & Shigley,

2005). California passed zoning requirements in the late 1920s and required all cities and

counties to prepare general plans in 1937. The general plan and zoning ordinances have

to be consistent, as required by law since 1971. It is the “consistency” principle in

planning. The change took place after post-war housing boom and planning trend switch

from cumulative zoning to exclusive zoning, which influenced the growth of suburbs.

15

The environmental movement to conserve and preserve natural resources influenced

many of the planning decisions during this time, as planning moved towards an

environmental focus. The year prior to California passing the “consistency” principle,

the state passed the California Environmental Quality Act (1970) following the passage

of the National Environmental Policy Act (1969) (Fulton & Shigley, 2005).

The fields of health and planning grew increasingly separated by the late 20th

Century. During this time public health started to focus more on lab work intense

investigation of human health concerns such as germs and air toxins (Corburn 2004).

There has never been any codification of health language requirements, and although

plans currently have some elements of health, they are largely implicit and not explicit.

Lubarsky (2007) argues that there are three legal approaches to integrating health in

general plans. The first is a legal requirement that codifies into California state law the

requirements for general plan elements and adds legally binding language that requires

collaboration between planning and health agencies. The second legal approach requires

adding a health element as part of general plan guidelines, and lastly Lubarsky (2007)

argues challenging elements of existing general plans in courts would reconnect general

plans and public health. Although California courts do have a long history of setting

precedent with various rulings regarding general plans and community planning,

challenging individual elements might be costly for many cities suffering from budget

cuts. Advocacy and leadership take much longer, but they might be less contentious and

less damaging to existing relationships between planners, experts, and community

leaders. The first two legal approaches are more feasible and flexible for agencies and

16

local governments as some are already moving towards collaborative efforts and

including health in their general plans.

The separation of health and planning changed the way health experts and

planners define health. Feldstein (2004) notes that “except as it relates to seismic safety,

hospitals, and similar situations general plans have rarely addressed health issues” (p.

11). Corburn (2004) argues that some of the problem lies in the language used to

describe health activities. For example, sustainability movements and walkable city

movements define additional bike lanes as more sustainable practices because they

encourage the reduction of vehicle miles traveled and therefore lower the pollution levels.

However, policies do not always address the health benefits of physical activity. Health

benefits are a secondary positive effect and not a central piece of the discussion. The

effect on human health is not central to the goals of the policies, and therefore, there is no

increased awareness or health outcomes expectation that can measure quality of life.

Current Public Health and Planning Policy Efforts

One of the first cities to adopt a health element as part of its general plan was the

City of Richmond. Richmond and Oakland are examples of low-income areas close to

industrial centers that have become case studies for the reconnection of health and

planning. Health and planning experts are reconnecting both fields in a variety of ways.

One example is the Contra Costa County’s Planning Integration Team for Community

Health (PITCH). The partnership includes the Community Development Department,

Health Services Department, and Public Works Department (Baer & Rattray, 2007).

17

Experts and advocates are increasingly using Health Impact Assessments (HIAs). HIAs

have a similar function to Environmental Impact Reports (EIRs), but focus on a

development’s impact on public health (Frank & Kavage, 2012). Many of these policies

are not widely used, as there is still debate over how much influence local planning

policy can have on health issues such as obesity.

There is still debate over the best way to decrease obesity rates. Hutch et al in

“Potential Strategies to Improve Public Health” (2011) outlines the community factors

and family and individual factors that cause the disproportionate health outcomes. The

researchers emphasize the need to create collaborative efforts to identify strategies to

reduce the health disparities because there is not one root cause of health problems.

What issues are “health” issues?

There is no uniform definition of health as it is composed of various issues.

Current health issues receiving attention are obesity, nutrition access, physical activity,

and asthma. Counties like Contra Costa and San Mateo have included mental health, and

safety from violence and homicide in their policies (Baer & Rattray). In “Healthy

Planning Policies: A Compendium from California General Plans” (2012) researchers

compiled a list of health policies from California cities that have adopted health policies,

and evaluated them for “innovative land use topics” such as raising the profile of public

health, health care and prevention, healthy food access, equity, and environment. The

article only presents sample topics but does not quantify findings. None of the cities, in

the article, is located in the San Joaquin Valley, but some cities included are located in

my Table 1 p. 7.

18

I was able to find toolkits that guide advocates on how to integrate health into

general plans. Two of the toolkits currently available online are Feldstein’s “General

Plans and Zoning: A Toolkit for Building Healthy Communities” (2007) and Raimi and

Associates “How to Implement and Create Healthy General Plans toolkit” (2012). The

Institute for Local Government produced “Land Use and Planning: Guide to Planning

Healthy Neighborhoods” (2010). Feldstein and Raimi outline a model resolution and

various language models that cities can use in their general plans. One of the models

uses language from the City of Benicia’s General Plan, which describes the dimensions

of optimal health to be the physical environment, the social environment, emotional

health, intellectual environment, and spiritual environment. The policy choices in the

models range from promoting drug free environments, promoting farmer’s markets,

requiring annual reports on community health, community gardens, and creating open

collaboration with the community.

The Institute for Local Government (ILG) (2010) Guide does not just focus on

general plans, but offers several alternative ways that cities can integrate health. The ILG

recommends the use of:

Local plans or specific plans that focus on one geographic area such as

subdivisions.

Local programs and services such as recreational programs offered by

parks and recreation departments.

Requiring property owners to maintain clean and safe areas through code

compliance and enforcement.

19

Economic development, and redevelopment which helps increase revenue

and improves the infrastructure of the city. Health status correlates

strongly with the economic status of places.

The toolkits are a good example of how cities and advocates can differ on the best

way to tackle chronic health conditions that exist in their communities. Cities are

struggling to balance their budgets and have limited resources to devote to overhauling

their general plans. The ILG recommendations provide alternatives that can be less

costly for cities, while the toolkits from Feldstein (2007) and Raimi (2012) focus on

changing the general plan, changing zoning codes, and creating area or issue specific

master plans. The toolkits recommend further research on funding take place as part of

healthy city planning.

I will discuss the adoption of sustainability policies in my next section, but the

only report that I was able to find that examined the adoption of health elements and

sustainability policies is the American Planning Association’s (APA) Healthy Planning

Report (2012) . In the study, the APA created an evaluative framework to analyze 18

comprehensive plans and four sustainability plans from cities across the nation. It used

79 questions to evaluate the plans. The APA found that most of the plans they evaluated

include active living goals that language is accessible to the average reader and that water

quality and environmental concerns were present. In addition, the APA found that only

two of their plans identified vulnerable populations, only three plans identified chronic

diseases or health disparities in their vision, and only two plans identified brownfield’s as

threat to human health. I will use the How to Create and Implement Healthy General

20

Plans Toolkit (2012) health language recommendations and the APA’s Healthy Planning

Report (2012) to create my own evaluation framework.

City Adoption of Health Promoting Policies

In this section, I examine the adoption of sustainability and the adoption of air and

climate change promoting policies. First, I outline the literature on sustainability

policies, as many sustainability principles affect health and their adoption might already

include public health outcomes as a goal. Secondly, I found no literature on local

governments’ adoption and implementation of state imposed state climate standards, but I

did find literature on local governments’ voluntary adoption of climate policy.

The most cited work in the following readings was Kent Portney’s (2002) work,

“Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously: a Comparative Analysis of Twenty-Four US

Cities.” In his study, he created a sustainability index with 34 elements of sustainability

divided into seven categories. Two of the major findings in his case study are that cities

that rely on polluting manufacturing industries as the base for employment and cities with

younger populations are cities that take sustainability less seriously (p. 374). He found

that population growth or rapid population growth does not put pressure on local

governments to adopt sustainability policies (p. 377). The case study focused on large

cities, but the findings are important because sustainability deals with the “triple bottom

line” or environmental protection, economic development, and social equity (Saha &

Paterson, 2008). The principles apply to environmental justice and social equity and are

one of the main tenets of health advocacy. There currently is no index available for

21

health related language, but the following readings add to Portney’s (2002) work and

findings.

A. Factors in City Adoption of Health Promoting Land Use Policies

In “City Adoption of Environmentally Sustainable Policies in California’s Central

Valley,” Lubell, Feiock, and Handy (2009) use Portney’s (2002) work and Conroy’s

(2006) recommendation to focus on less known communities and create an

Environmental Sustainability Index for the Central Valley. Lubell, Feiock, and Handy

(2009) find that adoption of environmental sustainability policies is a largely urban

phenomenon with cities that are more populous, more financially independent, more

socioeconomically advantaged, and have higher stores of intellectual capital. Portney

and Berry (2010) believe that demographic factors alone do not offer the full explanation

because large cities with similar economic resources do not always adopt sustainability

policies. Some do and some do not.

In their study, “Urban Advocacy Groups, City Governance, and the Pursuit of

Sustainability in American Cities” (2010), Portney and Berry find that there are very few

barriers to entry when comparing city governments to federal governments. There is also

very little lobbying opposition by interest groups; with the exception of zoning and land

use regulation by business groups at the city level. In terms of access to political

leadership, both business groups and neighborhood associations enjoy the same high

level of access. Support for sustainability is greater when labor unions, environmental

organizations, and neighborhood associations contact administrators. Portney and

22

Berry’s study is in line with sustainability studies by Zeering (2009) and Salvasen et al

(2008). Zeering, in his study of San Francisco Bay area cities, found that the way

economic development officers conceptualize sustainability affects programmatic

priorities. There are “aspiring city” officials that focus on future changes, “traditional

city” officials that focus on the retention of current business and economic development,

and “participatory city” officials that try to improve civic participation.

Salvesen et al, 2008, in a case study looking at implementation of local policies

that promote physical activity in Montgomery County, Maryland found that one of the

major issues with implementing physical activity policies is fragmentation among

agencies and coordination of policy implementation. The study used interviews to

examine knowledge, awareness, commitment and county capacity, and intergovernmental

coordination. The study found that knowledge and awareness did not have as much

impact as the commitment and leadership of county officials.

B. Air Quality and Climate Change Policies

The San Joaquin Valley has some of the highest asthma rates in the nation. Air

quality improvement is very important to the health of the residents in the area. The

region is unique, as the cities within its boundaries have to adopt air quality standards

through AB 170 (Reyes, 2003). The following literature offers some insight into cities’

decision to adopt air quality and climate policies.

Various studies available examine city adoption of climate change policy.

Krause’s (2009) results were consistent with Portney’s (2002) findings that increased

reliance on manufacturing in the local economy decreases the probability that a city will

23

commit to climate protection. Krause (2009) found mayor-council government type of

cities with higher levels of education and democratic political leanings were more likely

to adopt climate policy. Sharp, Daley, & Lynch (2011) studied membership in the

International Council of Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI). The Council offers

technical assistance to cities that pledge to reduce Green House Gas (GHG) emissions.

Consistent with Krause (2009), Sharp, Daley, & Lynch (2011) found that cities with

mayoral form of governments and high environmental interest group presence are more

likely to join ICLEI. However, unlike Krause (2009) and Portney (2002), they did not

find manufacturing presence to make a difference in a cities decision to join ICLEI, but

did not consider their results to say opposing interest do not make a difference in a city’s

decision to join ICLEI.

The San Joaquin Valley is required to include air quality standards in their general

plans because of AB 170. At the regional and county level, there has been recent

adoption of Blueprint smart growth principals through collaborative regional efforts

coordinated by COGs. They include health and air quality-promoting principles. A four

scenario study, conducted by Mark Hixon et al (2010), on the influence of regional

development policies and clean technology adoption on future air pollution exposure in

the San Joaquin Valley found that compact high density urban development combined

with added pollution controls at the local level can significantly reduced pollution levels.

Regional collaboration to plan for the long-term prosperity of the area is taking place

(Harnish, 2010).

24

Implications from My Research

Research on sustainability and land use tends to focus on urban areas and large

cities. Researchers are recommending more focus on smaller cities. In the literature, I

found that cities and counties that face population spillover pressures might not always

adopt sustainability or health promoting policies. Adoption of health promoting policies

tends to be an urban phenomenon with cities that are larger and financially independent

being more likely to adopt policies. If this is the case, I expect that larger cities in the

San Joaquin Valley will have more health promoting policies in their general plans

25

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this study to analyze how cities and counties in the San Joaquin

Valley are incorporating public health goals in their general plans. General plans are the

blueprints for the built environment for cities and counties in California. Traditionally

general plans have focused on issues such as noise reduction, sewer and clean water

services, exposure to hazardous materials, and seismic safety (Stair, Wooten, & Raimi,

2012). I will focus on the integration of public health goals and policies in general

plans. Public health concerns are becoming part of general plan language as research

has started to link chronic health conditions such as respiratory diseases, obesity,

nutrition, and physical activity to the built environment.

Although experts advocate for higher integration of health language in general

plans, they caution against clustering modern health issues into a health element without

integrating the health language into the other seven elements (Stair, Wooten, & Raimi,

2012). I will use the How to Create and Implement Healthy General Plans Toolkit

(2012) health language recommendations to create an analytical framework based on the

American Planning Association’s (APA) Healthy Planning Report (2012). I will also

build on the work done by the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR)

Annual Survey Results (2012). The survey includes various public health questions.

This chapter will first summarize general plan requirements, air quality

requirements, and smart growth planning in the San Joaquin Valley. I will then present

the major modern health issues as described by How to Create and Implement Healthy

26

General Plans Toolkit (2012). Next, I will outline my analytical framework based on

the APA’s Healthy Planning report (2012). Lastly, I will explain my case study

selection and evaluation research questions.

California General Plan Requirements

In this section, I will explain more in depth OPR’s advisory General Plan

Guidelines (2003), and summarize major planning changes in the region. The State of

California requires cities and counties to adopt a general plan under Government Code

§65300. Cities and counties must include seven elements: Land Use, Circulation,

Housing, Conservation, Open Space, Noise, and Safety (§65302). Cities and counties

can also include optional elements that are relevant to their long range planning and

needs under §65303. Some of the optional elements examples included in the General

Plan Guidelines (2003) are air quality, community design, and energy.

The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) is in charge of

periodically revising and updating the advisory guidelines (§65040.2) (OPR, 2003). The

2003 General Plan Guidelines include a section that discusses Sustainable Development

and Environmental Justice. They are not required elements in the general plan but they

deal with the three E’s in planning: Environment, Economy, and Equity. Sample issues

are mixed use development, job-housing balance, land use density, and open space &

parks recreation. Table 2 in the following page includes a summary of OPR’s General

Plan Advisory Guidelines (2003).

27

Table 2: Office of Planning and Research General Plan Advisory Guidelines

Office of Planning and Research General Plan Advisory Guidelines and Issues

Advisory Guidelines

Element

The element is the broadest in scope and plays an important role in

Land Use

zoning, subdivision, and public works decisions. The element lays out

the ultimate pattern of development for a city or county and is the most

representative of the general plan.

Distribution and location of housing, business, industry, open space &

agricultural land, public facilities, buildings, and grounds, and other

categories of public and private land uses

The element is the infrastructure plan that deals with the movement of

Circulation

people, goods, energy, water, sewage, storm drainage, and

communications. The element must correlate with the Land Use

element.

Major thoroughfares, transportation routes, sewage, plus other

infrastructure topics.

The element primarily focuses on the conservation of natural resources.

Conservation

Water, forests, soils, minerals, rivers, harbors, fisheries, wildlife, and

other natural resources.

The element guides the comprehensive and long-range preservation of

Open Space

open space land. It is the second most detailed in is statutory

requirements covered under§655561 and §65562 of the Government

Code. The element is the second broadest after the Land Use element.

Preservation of natural resources and outdoor recreation space

availability. Any parcel, area of land, or water that is dedicate to open

space such as bays, forest land, mineral areas, and areas of scenic or

historical significance.

The element guides land use decisions, location of transportation

Noise

facilities, and roads as they expose the community to high noise levels.

The element must analyze and quantify the levels of noise as well as

include possible implementation measures and solutions.

Major noise sources and existing and projected levels of noise.

The element guides local decisions related to zoning, subdivisions, and

Safety

entitlement permits. The goals of the safety element must be to reduce

risks of death, risk of injuries, property damage, earthquakes, and other

hazards.

Flood hazards, Seismic hazards, Fire hazard, Landslides, Other hazards

Usually a separate element it has the most detailed requirements under

Housing

Article 10.6 of the Government Code §65583 through §65590. Cities

and counties must assess what their existing and projected housing

needs are and update the element every five years.

Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA)

Note. Created using information from: Office of Planning and Research (OPR).(2012). General

Plan Guidelines 2003. Retrieved July 1, 2012 from:

http://www.opr.ca.gov/s_generalplanguidelines.php

28

The 2003 General Plan Guidelines recommend that city and county general plans

avoid any repetitiveness in the elements. The topics covered by the elements overlap,

and therefore, elements do not have to be separate elements as long as all statutory

requirements are included (OPR, 2003). The three guiding principles are: 1) all general

plans must include integrated, 2) they must be internally consistent, and 3) they must be a

compatible statement of policies (Government Code §65300.5) (OPR, 2003). They have

to be complete and include all seven elements, be readable to the public, and address

local relevant issues. They have to be in substantial compliance with statutory

requirements per Camp v. Mendocino County, and must plan only to the extent a problem

or opportunity exist §65300.7.

Planning in the San Joaquin Valley

Air quality is not a required element under the 2003 General Plan Guidelines.

However, because of Assembly Bill 170, San Joaquin Valley Cities and Counties had to

add it as an element or amend their general plans. The San Joaquin Valley Unified Air

Pollution Control District had to receive adopted amendments from Fresno and Kern

Counties by 2009 and Kings, Madera, Merced, Stanislaus, and Tulare Counties by 2010.

Cities and counties in the San Joaquin Valley must include goals, policies, and feasible

implementation strategies to improve air quality §65302.1. The four requirements under

AB 170 are:

1. A report describing local air quality conditions, attainment status, and state

federal air quality and transportation plans.

29

2. A summary of local, district, state, federal policies, programs, and regulations to

improve air quality.

3. A comprehensive set of goals, policies, and objectives to improve air quality.

4. Feasible implementation measures designed to achieve these goals (San Joaquin

Valley Air Pollution Control District, 2012).

The air quality amendments for the San Joaquin Valley are part of an effort to

improve health in the region. The Councils of Governments (COGs) and the Madera

County Transportation Commission created a collaborative effort to create the San

Joaquin Valley Blueprint program. The program addresses twelve smart growth

principles for the Valley. Each COG created blueprint principles, which the counties

adopted, and became part of the regional Blueprint program (Harnish, 2010). There are

62 cities in the San Joaquin Valley, and out of those cities, 46 cities with populations of

50,000 or less received technical help from the San Joaquin Valley Blueprint Integration

Project. The Integration Project assisted smaller cities that needed technical assistance

integrating the twelve smart growth principles into their general plans. The program was

set to end January 2013. The other 14 large cities are using services of the Smart Valley

Places program (Harnish, 2010).

Health in the General Plans of the San Joaquin Valley

The inclusion of health language related to chronic health conditions in general

plans is new and only a small amount of cities in California have created separate health

elements. OPR will be updating their guidelines this year and are considering including

30

health guidelines (OPR, 2013). OPR conducts an annual survey of cities and counties on

various planning topics and issues in the state. The 2012 Annual Survey Results were the

first to include health related questions.

The survey includes various questions on issues covered by the APA Healthy

Planning Report (2012) and the How to Create and Implement Healthy General Plan

Toolkit (2012). The OPR survey asked in what element are health promoting policies or

programs contained if the jurisdiction explicitly referenced health protection or

promotion in the city or county general plan.

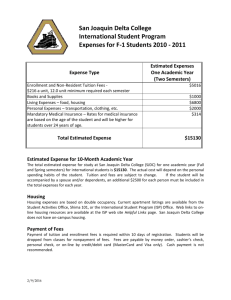

Figure 1: Health in San Joaquin Valley General Plan Elements

Note. Created using: Office of Planning and Research (OPR). (2012)Annual Survey Results

2012. Retrieved May 2, 2013http://www.opr.ca.gov/docs/2012_APSR.pdf

The surveyed received 454 responses for the question and out of those, 33 were

from San Joaquin Valley cities and counties. Cities and counties cited the safety element

the most, followed by the land use element, and open space (Figure 1). Thirteen San

31

Joaquin Valley cities responded they have programs or policies that ensured access to

grocery stores, citing the land use element the most. Out of all the cities in the San

Joaquin Valley that responded to the OPR survey, only the City of Stockton and the City

of Arvin responded that they had a health element. My preliminary review found that the

City of Arvin is in the process of creating a new general plan that includes a health

element, and their current general plan is not available online.

My research will build on OPR survey responses, as I will be looking at the

degree of inclusion of public health topics. The How to Create and Implement Healthy

General Plan Toolkit (2012) offers suggestions on creating healthy general plan language

and the analytical framework created by the APA looks into degrees of health inclusion

in general plans. Degrees of inclusion can range from a simple mention of the issue to a

full plan that includes success indicators. As part of my case study selection process, I

did preliminary review of San Joaquin Valley city and county general plans using the

following analytical framework:

Analytical Framework

How to Create and Implement Healthy General Plans toolkit (2012) includes a

model baseline assessment of health issues in the community and model health language

for general plans. Table 3 summarizes some of the model health issues that the toolkit

recommends cities and counties include in their general plans. OPR’s advice about

Sustainability and Environmental Justice includes some of the tools in the toolkit; such as

mixed use development, job-housing balance, land use density, open space, and parks and

32

recreation. The smart growth principles of the Valley Blueprint also cover mixed used,

land use density, the preservation of open space and farmland, transportation, and

fostering community and stakeholder collaboration. With this in mind, I expect cities and

counties to include public health topics in their general plans.

The toolkit warns that if cities or counties decide to include a health element in

their plans, they should pay special attention to including the variety of issues holistically

throughout their plans. Effective health change will only happen if local health officials

insert the concern throughout the plan (Stair, Wooten, & Raimi, 2012). The American

Planning Association (APA) Healthy Planning Report (2012) includes a qualitative tool

to evaluate the plans of 18 cities in the United States. My analytical framework and

model uses its final published report. Table 3 includes some of the health topics

suggested by the toolkit and the topics the APA used in its evaluation of city and county

general plans. I created my evaluation topics based on their suggestions. I will explore

accessibility, physical activity, transportation, air and water, food and nutrition, mental

health and social capital, and safety and health care access.

33

Table 3: Advisory Health Topics Used to Model Evaluation Framework

Toolkit Health Assessment Issues

Overall Health of the Community

Assessment of major health concerns

Links to the build environment

Vulnerable populations

Obesity/overweight rates

Physical Activity

Residential and commercial areas

proximity to parks, open space, and

recreational facilitie

Mix use

Job-housing balance and match

Land use density

Nutrition

Access to healthy food

Number of fast food restaurants and

offsite liquor retailers

Local agricultural resources

Food distribution

Mental Health and Social Capital

Participation

Stability

Community safety

Air and Water

Asthma and other respiratory ailments

Air quality/toxic contaminants

APA Evaluation Topics

Broad Issues

Health included in vision statement

Health is in guiding principles

General plan procedure is accessible

Active Living

General

Active transport

Recreation

Injury

Food and Nutrition

Access to food and healthy foods

Water

Land use

Social Cohesion & Mental Health

Housing quality

Green & open space

Noise

Public safety/security

Environmental Exposures

Air quality

Water quality

Brownfields

Transportation

Health & Human Services

Traffic injuries and fatalities

General

Mode split

Accessibility to health and human

services

Commuting

Aging

Transportation network

Emergency Preparedness

Climate change

Natural and human-caused disaster

Infectious disease

Note. Created using information from: the APA Healthy Planning Report (2012) and the How to

Create and Implement Healthy General Plan Toolkit (2012).

34

Case Study Selection

In the first phase of APA’s research, they conducted a survey that identified 890

cities whose plans contained the term “public health.” The Centers for Disease Control

(CDC) added a list of 45 cities to its pool. The APA narrowed its list to 18 cities and

counties by using the criteria listed on Table 4.

To select my case studies, I looked for general plans that included “health” in the

title of their elements and health language that mentions the following issues: obesity,

nutrition, and physical activity. Appendix A includes all sixteen cities and counties in the

San Joaquin Valley that include “health” in their general plans.

Table 4: San Joaquin Valley Case Study Selection Criteria

APA Criteria

1. Explicit reference to public health

2. Official adoption by city or county

ordinance

3. Inclusion of 10 or more health

related goals and policies as

outlined in the survey

4. Geographic spread

5. Urban, suburban, and rural contexts

6. County as well as city plans

Criteria for San Joaquin Valley Evaluation

1. Publicly available and published online

2. Officially adopted general plans only,

no drafts

3. General plan contain element with

term “Health.”

4. Urban, suburban, and rural contexts

5. City and county general plans

Note. Modeled after the APA Healthy Planning Report (2012)

Research Questions

The major goal of my study is to identify what type of health topics are being

covered in general plans in the San Joaquin Valley and identify if there are any common

regional success indicators. My study will focus on answering the following research

questions:

35

1. What type of health issues and topics are included in city or county general plans

in the San Joaquin Valley?

2.

Do the general plans include goals, objectives, and policies the health issues and

topics they cover?

3. How do cities and counties plan to track the success of health related policies?

The evaluation part of my study surveys the general plans according to a scoring

system based on the APA’s Healthy Planning (2012) evaluation tool. The APA used

Edward and Haines (2007) plan evaluation framework to score the plans using a score of

0, 1, or 2. I will use the same scoring system.

1. A score of 0 if there is an absence of language.

2. A score of 1 if the language is present but there is only background information.

3. A score of 2 if the policy is comprehensive in nature and includes goals or policy

actions.

The APA study used eight categories to create 79 evaluation questions for its 18

case studies. The eight categories the APA used overlap the How to Create and

Implement Healthy General Plans (2012) toolkit categories. I based my evaluation

categories on both the APA and toolkit categories. One limitation of my analysis is that I

will be the only reviewer of the general plans; the APA had two experts score the general

plans the study evaluated. In addition, I am working with a much smaller sample as I am

only focusing on the San Joaquin Valley region. I am also only basing my study on

general plans that are available online. Although my analysis only looks at 16 cities that

36

during my preliminary review had a health element, only three cities and one county had

health language related to nutrition, obesity, or physical activity, which are public health

issues that concern the region.

Evaluation Questions

I separated evaluation questions into goals and policies for each public health

topic. I used the APA study to create a set of evaluation questions (Table 5 in next page).

In the following chapter, I will outline the results of my general plan evaluation. I expect

that cities will be more heavily focused on health issues they can influence through better

planning goals, but not be as focused on issues that might be influenced by lifestyle

factors such as obesity.

37

Table 5: Health Topics and Evaluation Questions

Introduction

and Access

Physical

Activity

Transportation

Air and Water

Food and

Nutrition

Mental Health

and Social

Capital

Safety &

Health Care

Access

Does Introduction includes Explicit concern for public health?

Does Introduction includes topics such as EJ, sustainability, or smart growth?

Policies target community participation?

Language used is easy to read and understand?

Visual elements aid understanding?

Physical activity identified as important to community life?

Goals plan for residential areas proximity to recreational areas?

Goals include mixed use planning, a walkability plan, or biking plan? Goals target

increasing children’s physical activity?

Policies to expand the number of parks or recreational facilities?

Policies to create joint use facilities for recreational purposes?

Policies to expand any walking or bicycle trails?

Policies that support “safe routes” to school?

Goals target increasing public transportation access?

Goals aim to reduce traffic related injuries and fatalities?

Policies plan for sidewalks or “complete street” plans?

Policies include transportation plans to reduce vehicle miles traveled?

Policies aim to expand public transportation networks?

Goals include air quality?

Goals aim to reduce asthma rates and other respiratory health illness?

Goals include increasing water access?

Policy requirements to improve air quality?

Policies targeting asthma rates and other respiratory illness?

Policies plan on increasing water access to rural communities?

Goals encourage grocery stores, produce markets, or farmer’s markets?

Goals aim to conserve or use local agricultural resources

Policies include planning for grocery or food retailers?

Policies plan for farmers markets?

Policies target better local food distribution?

Policies encourage community gardens or non-traditional food sources?

Policies target restricting fast food or liquor store retailers?

Goals encourage expanding mental health services or awareness?

Goals encourage aging in place?

Goals plan for the social life of a county or city?

Policies include the expansion of mental health facilities?

Policies encourage people to age in place?

Policies target a job housing balance?

Goals target diabetes, obesity, asthma, or physical activity?

Goals include accessibility goals and objectives for health care access?

Goals plan healthcare access to low income or rural communities?

Policies target chronic health conditions explicitly?

Policies expand healthcare facilities in low income or rural areas?

Policies encourage safe violence free communities?

Note. Modeled after Note. Created using information from: the APA Healthy Planning Report

(2012) and the How to Create and Implement Healthy General Plan Toolkit (2012).

38

Chapter 4

GENERAL PLAN EVALUATION RESULTS

Planning is a dynamic and always changing process for cities and counties. The

general plan is a blueprint, and a living document that changes as needs change. In this

chapter, I will focus on the results of my evaluation of San Joaquin Valley general plans.

I will first present the results of my case study selection and will conclude with a

discussion of health in general plans in the San Joaquin Valley.

Case Study Selection Results

My evaluation only includes general plans that have a health element. One of the

concerns expressed in the How to Create and Implement Healthy General Plans Toolkit

(2012) is that health issues need to be included throughout the general plan and not

concentrated in one health element. I only evaluated officially adopted general plans, no

drafts: cities and counties will publish draft general plans for public viewing before

adoption and might not update the fully adopted general plan to their websites. To make

the evaluation reliable I only focused on general plans that had an adoption date.

I excluded general plans that are going through and update process and general

plans that had a health element but have a publishing date prior to 2003. The final case

study selection list based on the first four case study criteria includes Kings County,

Merced County, Tulare County, the City of Ceres, the City of Madera, the City of

Newman, the City of Ridgecrest, the City of Ripon, the City of Patterson, the City of

Porterville, and the City of Tehachapi. I also excluded Merced County’s plan because the

document on the County’s website was only a draft.

39

My evaluation contains no large cities as the City of Fresno and the City of

Visalia are currently updating their general plans, and the City of Bakersfield and the

City of Stockton do not make their general plans available online. During my

preliminary review, I only identified Tulare County, the City of Madera, and the City of

Tehachapi as having health language related to obesity, diabetes, nutrition, or physical

activity (Appendix A, p 70). However, during my evaluation, I identified Tulare County,

the City of Porterville, and the City of Ridgecrest. Kings County was the only

jurisdiction that had an in depth discussion of obesity in its jurisdiction and included data.

Table 6: City and County Profiles

City or County

Population Census 2010

152, 082

Kings County

442, 179

Tulare County

61, 416

Madera (Madera County)

10, 224

Newman (Stanislaus County)

20, 413

Patterson (Stanislaus County)

54, 165

Porterville (Tulare County)

14, 164

Ridgecrest (Kern County)

14, 297

Ripon (San Joaquin County)

14, 414

Tehachapi Kern County

Note. Population statistics taken from quickfacs.census.gov.

General Plan Update

2010

2012

2009

2007

2010

2008

2008

2006

2012

Evaluation Results

In this section, I examine and discuss my evaluation results. I first present my

results by topic issue and then include a discussion of my research questions. The topic

issues appear in this order: introduction and access, physical activity, transportation, air

and water, food and nutrition, mental health and social capital, and safety and health care

access.

40

Introduction and Access

Introduction

Introductory statements set the overall vision of local governments. From, the

literature and toolkit recommendations, introductory statements can signal public health

to be an important feature of a community. In this category, I first evaluated whether

general plans contained language that explicitly discussed public health, and secondly if

introductory statements included any mention of health promoting policies such as

environmental justice, sustainability, or smart growth,

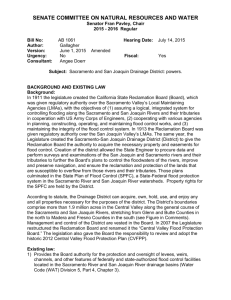

Figure 2: Introduction and Access

Introduction and Access

There is Explicit concern for

public health

Includes EJ, Sustainability, or

smart growth

2

6

3

1

5

Goal or Policy

Includes community participation

policies

8

Includes language easy to read

and understand

8

Includes visual elements to aid

understanding

1

01

Background

No mention

6

10

3

0

Note. Created using information from city and county general plans. See Appendix A p. 70

and B p. 74.

I found that public health is included as an overall goal or in background

information, with six out of nine general plans containing a public health or a community