PowerPoint Sunusu

advertisement

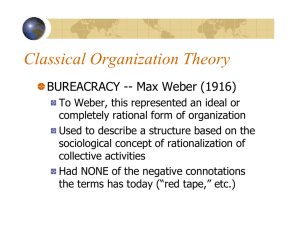

Fundamentals of Organizational Theory and Management What is theory anyway? A theory is a broad explanation of a phenomenon or phenomena that is testable, falsifiable and has multiple lines of evidence. Theories are formed after numerous hypotheses are vetted using the scientific method. Hypotheses are tested, data is collected, and the results are documented, shared and retested. Then, a theory that explains the data and predicts the outcomes of future experiments is formed. Public administration means public organizations and their management. The relationship between size, complexity, specialization, and the need for coordination is extremely important for public agencies. Organizational theory studies virtually everything that is associated with organizations. It is a large field of study that includes examining organizational design, motivation, organizational culture, managerial styles, group behavior, leadership, and communication. Concepts and practices like management by objectives, transactional analysis, quality circles, job enrichment, and organizational development are all a part of organizational theory. The goal of organizational theory is to enhance our understanding of organizations and organizational life and, hopefully, discover ways to improve organizations. In this process, the essential question is; how do they work? Large organizations are complex configurations comprised of people, rules, and regulations, structures, materials, equipment, and expertise. No doubt, all these aspects are important, but management, people and organizational design have received the most attention by researchers. There are a number of approaches or models that can be used to study public organizations but three are more significant models than others: Political, organizational and humanistic approaches. Political Approaches Two politically oriented models are still widely used today: structures / functions model and public policy model. The models that examine structures and functions define public organizations in a way similar to describing the anatomy of the human body or the mechanical configuration of an automobile. These models diagram the formal legal powers and relationships among organizations. The emphasis is on the formal organization, its procedures, and legal structures. This model sees organizations as a system of components that perform a variety of functions and activities, which includes the behavior of administrators and agencies. The problem with this approach is that it fails to adequately describe the behavior that occurs within agencies and seldom focuses on how agencies are managed. Moreover, policy outcomes are viewed simply as the result of interaction within the formal institutions of government. It maps out the legal, procedural, and structural arrangements found in public organizations, which is something that we need to know to understand public agencies. In public policy model it is focused on the complexities and dynamics of the public policy process. This includes the agencies, decision makers, and players who are involved in making public policies. The process develops because of conflicts between competing interest groups who have different values and objectives. Interest groups seek to influence outcomes in the process by using money, votes, and resources to gain access to decision makers. This model is primarily found in public policy analysis. It is typically a rigorous form of inquiry that provides great insight into the real workings of the public policy process and how agencies behave in the process. However, it reveals very little about managerial dimensions of organizations or other aspects of organizational life. Political approaches are interesting and useful since they define the organizational, procedural, and legal structure of political institutions and agencies. They also enhance our understanding about the behavior of the institutions, groups, and people involved in the policymaking process. Organizational Approaches Organization-based approaches are considered to be the true beginning of organizational theory in the managerial sense of the term. These approaches were the first to shed light on many of the realities of organizations and organizational life. Organizational models are multi-disciplinary, involving many disciplines outside of political science and public administration. Two thinkers are important in framing the basics of organization theory: Max Weber (1864-1920) and Frederick Taylor (1856-1915). Weber had the least impact on practitioners at the time; his impact was much greater on academicians. In the modern world, Weber’s description of bureaucracy still helps to shape the way that most of us view large organizations. We should keep in mind that his descriptions were about an ideal type or model bureaucracy. His model reflected the fundamental elements of efficient and effective organizations that he saw developing in Germany in the 19th century. For Weber, the bureaucracy was the only way that modern societies could organize themselves. Modern societies were simply too complex to be administered without bureaucracy. For Weber, bureaucracy was simply an organization that had certain characteristics and was organized in a rational way. Weber described a hierarchical structure arranged like a pyramid, with each position responsible to the one above it. Labor is divided, and specialized duties are assigned to each position. The organization is governed by rules, thus, decision making is based on the application of standardized rules that apply equally to everyone and are designed to accomplish organizational goals. The bureaucracy is impersonal; officials make decisions according to the responsibilities assigned to their positions. Legitimacy is essential in bureaucracy and it comes from those standardized rules and regulations that apply to everyone. Selection and promotion are based on merit using objective standards. Weber’s legal-rational model has elements such as; Fixed and official jurisdiction, ordered by rules and administrative law, regular activities distributed in a fixed manner, authority by directives according to fixed rules, rights and duties of administrators prescribed by law, management based on written documents that are maintained in files, separation of public from private lives of officials, Positions held for life, free from political and personal considerations, which confers independence, and many more similar elements that we see in our bureaucratic structure. Weber believed that rationally organized bureaucracy was the most efficient form of administration. He also foresaw problems with bureaucracy and indicated that once it is established, it is among those social structures that are the most difficult to destroy. As bureaucracy grows and becomes more powerful, it turns on the very society that created it and attempts to reorder society into categories of stability and rationality. Frederick Taylor studied another dimension of organizations, namely, the part that is directly involved with production. All organizations have two primary types of behavior: the collective behavior of the organization as a whole that is reflected in its output, and the internal behavior of its members. For many years, the focus in studying business organizations was on finding the right methods to get workers to be more productive, and therefore achieve greater output. This notion fascinated Taylor. Workers were thought to be lazy and only segmentally involved with their work. The primary motivator was assumed to be money, and management’s job was to use science to find the best way to perform tasks and then train the workers to follow these procedures. The formula was rather simple: Science directs, money motivates, and workers will produce. This was the guiding doctrine in the world of business administration, and it was provided by the principles of Frederick Taylor’s scientific management. Taylor was a controversial figure even during his own time and the ideas espoused in his scientific management principles aroused distrust and suspicion among workers who feared the potential of exploitation. During the 1920s, efficiency experts with stopwatches symbolized everything that clerical and blue-color workers feared the most from the dehumanizing effects of scientific management. Workers were viewed as “cogs in the wheel” to be managed by the “carrot and the stick”. It should come as no surprise that the American labor movement was strongest in industries where mass production and scientific management techniques were widely used. Taylor’s organization was viewed as a “closed system” that focused on production and efficiency. The emphasis was at the lower levels of the organization because that was where products were produced. Although Taylor is best remembered for trying to find the “one best way” of performing a given task, his position contained four main principles that delineated what he saw as management’s duties and responsibilities in teaching workers Conducting studies to find the best way to perform tasks. Selecting the best workers and properly training them. Bringing together the science and trained workers by offering some incentive to the worker. Cooperation with workers by having management performs part of the work previously performed by workers. If management is to teach workers the “one best way” to do something, they must know how to do it themselves. Taylor predicted that because of this sharing of work, labor strikes would not occur if scientific management were properly used. Although Taylor’s ideas may seem dated, they are still very influential in modern management and thought. With respect to the study of business, time and motion studies are still done, and the idea of trying to find the most efficient way to produce goods and services is still very much alive and well in the new century. Like business administration, public administration had a lot of faith in science to provide the principles and procedures needed to create more efficient organizations. Many believed that a science of administration was possible that administration could be similar to biology, physics, and other established sciences. Using science to learn about organizations proved to be useful and revealed much about organizations, but the hope that science would reveal a universal set of principles of administration was never fulfilled. Herbert Simon dismissed the idea of using the principles as guiding wisdom because he saw the principles as being mutually contradictory. For instance, at the same time that they called for tall organizations to ensure that the chain of command was followed and that proper authority was maintained because everyone would know exactly who to report to, the principles also called to limit the levels of hierarchy to ensure that communication did not get distorted flowing through the chain of command, which suggests that the organization be as flat as possible. How can an organization be both tall and flat? Simon and others argued that principles are often simply too vague to have meaningful application. Simon literally went principle by principle and showed that a counter principle existed for virtually every one of the tenets of administrative science, at least as it was defined at the time. Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933) was one of the leading critics of scientific management and the ideals of the principles of administration long before it became popular to criticize them. The basic assumptions of scientific management rested on the belief that gathering data and utilizing the scientific method would lead to the discovery of the one best way to perform a given task. This view assumed that a fact was constant over time that a fact today was the same fact yesterday, and would still be a fact tomorrow. Follett essentially argued for what the scientific community today recognizes as relativism, and she also argued for a form Today she is considered to be among the greatest of the early public administration thinkers. She argued that the value of every fact depends on its position in the whole world process and is bound by its multitudinous relations. Facts must be understood as the whole situation, considering whatever sentiments, beliefs, and ideals enter into it. The world and its social organizations are not frozen; they are always changing and evolving. The idea of experts with a limited scope or perspective is suspect, since one becomes an expert not by being a specialist in a small area but by applying insights into the relationship of the specialty to the whole. Process is important in ensuring that administration is public. Mary Parker Follett’s positions were the antithesis of both Taylor’s scientific management and many of the tenets of classic public administrationists at the time. The paradigm of the time focused on chain of command, span of control, line positions being superior in power to staff positions, and the like but these were simply not what Follett saw as the most important elements of organizations. For Follett, the organization itself was a static structure, regardless of the design; it was the human element that made organizations dynamic. The next wave of organizational approaches rejected the administrative science idea that organizations were closed systems. Closed-system models focus on the organization, its internal structures, internal dynamics, and decision-making processes with little regard to the external environment. These models recognize the existence of the world outside of the organization, but it is management’s responsibility to control external environmental factors to limit their impact on the organization. Open-system models assume that the external environment influences the organization. Because organizations depend on resources from outside the organization, open-system approaches emphasized the relationship between the organization and its larger environment. These models recognized that organizations alter their structure, functions, and output in response to laws, interest groups, changing conditions, and values that are accepted by the larger society. System theory emphasizes the interactive and interrelated set of elements that affects the organization, usually conceptualized as inputs entering the system, the processing of the inputs back into the system. Since the process is continuous, an organization is constantly undergoing change. Weber’s model of bureaucracy is technically an open system. Humanistic Approaches Some researchers felt that existing models and theories failed to adequately explain how organizations really worked. That is why another perspective was needed – the humanistic approaches that focus on the people who work in organizations. By the 1940s organizational theory was changing. The humanistic approaches, which included a major subfield called organizational psychology, provided new insight by focusing on the individuals who work in organizations. The new focus included taking a careful look at such things as decision making, leadership, motivation, and reward systems. Much of the focus of humanism is on the individual or small groups of individuals and organizational conditions. Workers attitude toward their work might be more important than environmental conditions in productivity level. The mood of workers is important in increasing their productivity. Worker’s job satisfaction is directly related to productivity. The emphasis of the organizational humanists was on developing techniques for leadership, conflict resolution, and decision making that recognized the importance of expanding employee participation in the organization. Abraham Maslow developed his influential needs theory of motivation to illustrate that humans have needs that must be fulfilled. Productivity is improved by greater communication, feedback, and worker involvement in self-managed work teams. This is a radical shift from Frederick Taylor’s ideas. Organizational humanism has advantages over the other approaches by providing much deeper insight into the core of organizational life. Its focus on the needs of individuals rather than on an abstract political system or the mechanistic diagrams of organizational theorists provides insight about what might be done to improve the relationships between employees and organizations. One obvious criticism is that organizational humanism focuses so much on the needs of employees that it deemphasizes efficiency and productivity in organizations. A happy worker is not necessarily a productive worker, and a less-than-happy worker is not necessarily an unproductive worker. These three approaches tell us a great deal about organizations, the legal relationships between public organizations, how the conceptualizations apply to the real world, and the needs and relationships that exist within organizations. Most agree that no universal principles exist to be uncovered, but each theory gives us a better understanding of the complexities of organizations and the people who work in them.