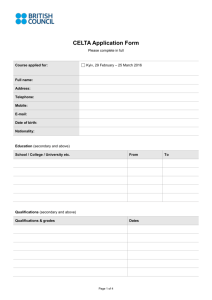

Document

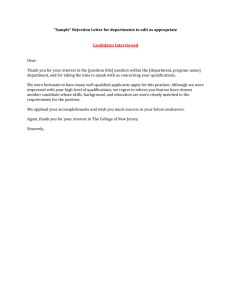

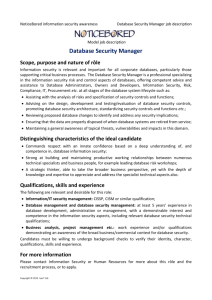

advertisement