Contracts outline - A grade - anonymous

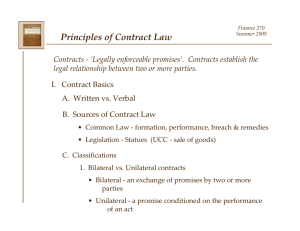

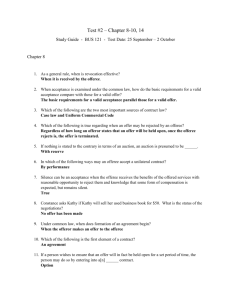

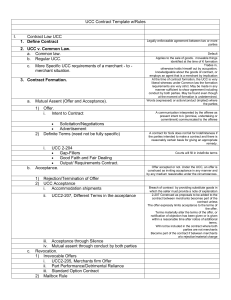

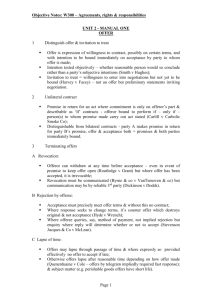

advertisement