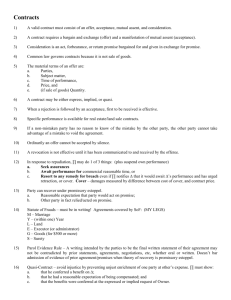

Consideration (pp. 23-29, 41-43, 127-30, 133-36)

advertisement