Part I - Alaska School Psychologist Association

advertisement

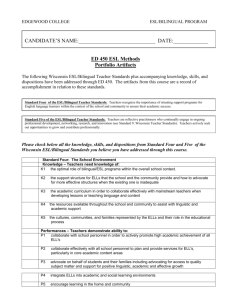

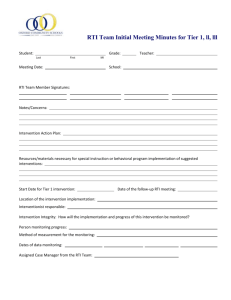

Square Pegs in Round Holes: Addressing educational challenges for culturally and linguistically diverse learners. Alaska School Psychologists Association October 15, 2015 Samuel O. Ortiz, Ph.D. St. John’s University Diversity is Everywhere in the U.S. Diversity is Everywhere in the U.S. Levels of Educational Services for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Children I. GENERAL EDUCATION – Equity Primary language (L1) instruction for all LEP children English language development (ELD) instruction for all children Curriculum that integrates and utilizes culturally relevant materials Affirmation of acquired knowledge and experiences II. PRE-REFERRAL - Responsive assistance Recognition of cultural and linguistic variables affecting achievement Implementation and systematic monitoring of curricular modifications (e.g., RTI) Culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions Utilization and exhaustion of general education resources III. ASSESSMENT - Bias Reduction Transdisciplinary approach based on data from pre-referral process Recognition of cultural and linguistic variables affecting test results Modifications and adaptations of traditional techniques and practices Non-discriminatory interpretation of all data within cultural/linguistic context IV. SPECIAL EDUCATION - Entitlements and Rights Specially designed instruction and services according to needs (IEP) Continued primary language (L1) and English language development (ELD) Culturally and linguistically appropriate IEP goals and objectives Coordination between general education and special education teachers Academic Attainment and Instructional Practices for English Language Learners Although many effective instructional practices are similar for both ELLs and non ELLs why does instruction tend to be less effective for ELLs? Because ELLs face the double challenge of learning academic content and the language of instruction simultaneously. To understand the implications of this challenge requires a good understanding of early child development and the interaction between language, cognition, and academic achievement. Source: Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. American Educator, 32 (2) pp. 8-23, 42-44. Comprehensible input is essential in order to progress through these stages Stages of Language Acquisition Pre-Production/Comprehension (no BICS) Sometimes called the silent period, where the individual concentrates completely on figuring out what the new language means, without worrying about production skills. Children typically may delay speech in L2 from one to six weeks or longer. • listen, point, match, draw, move, choose, mime, act out Early Production (early BICS) Speech begins to emerge naturally but the primary process continues to be the development of listening comprehension. Early speech will contain many errors. Typical examples of progression are: • yes/no questions, lists of words, one word answers, two word strings, short phrases Speech Emergence (intermediate BICS) Given sufficient input, speech production will continue to improve. Sentences will become longer, more complex, with a wider vocabulary range. Numbers of errors will slowly decrease. • • three words and short phrases, dialogue, longer phrases extended discourse, complete sentences where appropriate, narration Beginning Fluency Intermediate Fluency (advanced BICS/emerging CALP) With continued exposure to adequate language models and opportunities to interact with fluent speakers of the second language, second language learners will develop excellent comprehension and their speech will contain even fewer grammatical errors. Opportunities to use the second language for varied purposes will broaden the individual’s ability to use the language more fully. Advanced Fluency • give opinions, analyze, defend, create, debate, evaluate, justify, examine Source: Krashen, S.D. (l982). Principles and Practice in second language acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press. Language Proficiency vs. Language Development in ELLs Change in W Scores Phonological Processing Vocabulary 5 6 7 8 9 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 Age Source: McGrew, K. S. & Woodcock, R. W. (2001). Woodcock-Johnson III technical manual. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing. 80 90 95 What is Developmental Language Proficiency? Example CALP Level - ◦ ◦ ◦ Letter Word ID Dictation Picture Vocabulary RPI 100/90 94/90 2/90 SS 128 104 47 ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Reading-Writing v. advanced 100/90 Writing fluent 94/90 Broad English Ability fluent 94/90 Oral Language limited 27/90 123 104 104 65 ◦ ◦ ◦ Verbal IQ Perf. IQ FSIQ-4 69 82 72 PR CALP 97 59 <.1 - 94 61 59 1 6 4 4 3 verbal “thinking” skills continue to lag in development What is Developmental Language Proficiency? Example ◦ Can read the following words: ◦ Great, become, might, shown, explain, question, special, capture, swallow ◦ Cannot name the following pictures: ◦ Cat, sock, toothbrush, drum, flashlight, rocking chair ◦ Can understand simple grammatical associations: ◦ Him is to her, as ___ is to she ◦ Cannot express abstract verbal similarities: ◦ Red-Blue: “an apple” ◦ Circle-Square: “it’s a robot” ◦ Plane-Bus: “the plane is white and the bus is orange” ◦ Shirt-Jacket: “the shirt is for the people put and the jacket is for the people don’t get cold” Developmental Language Proficiency and IQ in ELLs 105 100 95 90 Standard Score 85 80 75 70 65 60 55 Low BICS AVG VIQ Intermediate Bics AVG PIQ Source: Dynda, A.M., Flanagan, D.P., Chaplin, W., & Pope, A. (2008), unpublished data.. Hi BICS Broad Eng Ability Understanding First and Second Language Acquisition Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) ability to communicate basic needs and wants, and ability to carry on basic interpersonal conversations takes 1 - 3 years to develop and is insufficient to facilitate academic success Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) ability to communicate thoughts and ideas with clarity and efficiency ability to carry on advanced interpersonal conversations takes at least 5-7 years to develop, possibly longer and is required for academic success Cummins’ Developmental Interdependence Hypothesis (“Iceberg Model”) BICS is the small visible, surface level of language, CALP is the larger, hidden, deeper structure of language each language has a unique and Separate Underlying Proficiency (SUP) proficiency in L1 is required to develop proficiency in L2, Common Underlying Proficiency (CUP) facilitates transfer of cognitive skills BICS - L2 BICS - L1 SUP - L1 CALP - L1 SUP - L2 COMMON UNDERLYING PROFICIENCY CALP - L2 (CUP) Source: Illustration adapted from Cummins (1984) Bilingual And Special Education: Issues In Assessment and Pedagogy . Developmental Implications of Second Language Acquisition If a second language (L2) is introduced prior to the development of CALP in the native language (L1), and if the L2 effectively replaces the L1 and its role in fostering CALP, academic problems will result. However, the language of instruction, parental education, continued opportunities for L1 development, and the age at which the second language is introduced, are factors that can affect development of the second language and expectations of academic progress in a positive way. L1 L2 L1 L2 HIGH L1 (CALP) LOW L1 (BICS) HIGH L2 (CALP) Type 1. Equal Proficiency "true bilingual" Type 3. Atypical 2nd Language Learner "acceptable bilingual" LOW L2 (BICS) Type 2. Typical 2nd Language Learner "high potential" Type 4. At-risk 2nd Language Learner "difference vs. disorder" L1 L2 L1 L2 Dimensions of Bilingualism and Relationship to Generations Type Stage Language Use FIRST GENERATON – FOREIGN BORN A Newly Arrived Ab After several years of residence – Type 1 Ab Type 2 Understands little English. Learns a few words and phrases. Understands enough English to take care of essential everyday needs. Speaks enough English to make self understood. Is able to function capably in the work domain where English is required. May still experience frustration in expressing self fully in English. Uses immigrant language in all other contexts where English is not needed. SECOND GENERATION – U.S. BORN Ab Preschool Age Acquires immigrant language first. May be spoken to in English by relatives or friends. Will normally be exposed to Englishlanguage TV. Ab School Age AB Adulthood – Type 1 At work (in the community) uses language to suit proficiency of other speakers. Senses greater functional ease in his first language in spite of frequent use of second. AB Adulthood – Type 2 Uses English for most everyday activities. Uses immigrant language to interact with parents or others who do not speak English. Is aware of vocabulary gaps in his first language. Acquires English. Uses it increasingly to talk to peers and siblings. Views English-language TV extensively. May be literate only in English if schooled exclusively in this language. THIRD GENERATION – U.S. BORN AB Preschool Age Acquires both English and immigrant language simultaneously. Hears both in the home although English tends to predominate. aB School Age Uses English almost exclusively. Is aware of limitation sin the immigrant language. Uses it only when forced to do so by circumstances. Is literate only in English. aB Adulthood Uses English almost exclusively. Has few opportunities for speaking immigrant language. Retains good receptive competence in this language. FOURTH GENERATION – U.S. BORN Ba Preschool Age Is spoken to only in English. May hear immigrant language spoken by grandparents and other relatives. Is not expected to understand immigrant language. Ba School Age Uses English exclusively. May have picked up some of the immigrant language from peers. Has limited receptive competence in this language. B Adulthood Is almost totally English monolingual. May retain some receptive competence in some domains. Source: Adapted from Valdés, G. & Figueroa, R. A. (1994), Bilingualism and Testing: A special case of bias (p. 16). Parallel Processes in Development: Education follows Maturation LANGUAGE ACQUISITION COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Preproduction Knowledge Early Production B I C S Emergent Speech Beginning Fluent C A Comprehension B I C S Application Analysis C Intermediate Fluent L A Synthesis B I C S A L P Advanced Fluent Pre-Readiness Training Readiness Training Basic Skills Training C L P ACADEMIC INSTRUCTION Appropriate Instruction/Assessment CULTURAL CONTEXT I C S C Early Conceptual Development P Evaluation B A L P Advanced Conceptual Development Education follows maturation. Black Slide Kimani Ng’ang’a Maruge A Google doodle honoring Maruge Misconceptions about Learning and Language Acquisition • Accent IS NOT an indicator of proficiency—it is a marker regarding when an individual first began to hear/learn the language • Children DO NOT learn languages faster and better than adults do—they only seem to because they have better pronunciation but CUP aids adult learners considerably • Language development CAN NOT be accelerated—but having developed one language to a high degree (CALP) does help in learning a second language more easily • Learning two languages DOES NOT lead to a kind of linguistic confusion—there is no evidence that learning two or more language simultaneously produces any interference • Learning two languages DOES NOT lead to poor academic performance—on the contrary, students who learn two languages very well (CALP in both) tend to outperform their monolingual peers in school • Code-switching IS NOT an example of a language disorder and poor grammatical ability—it is only an example of how bilinguals use whatever words may be necessary to communicate their thoughts as precisely as possible, irrespective of the language Developmental Implications of Early Language Difference The 30 Million Word Gap • according to research by Betty Hart and Todd Risley (2003), children from privileged (high SES) families have heard 30 million more words than children from underprivileged (low SES) families by the age of 3. • in addition, “follow-up data indicated that the 3-year old measures of accomplishment predicted third grade school achievement.” Source: Hart, B. & Risley, T. r. (2003). The Early Catastrophe: The 30 million word gap. American Educator 27(1), 4-9. Developmental Implications of Early Language Differences: When do ELLs “catch up?” 60 Cumulative Hours of Language Exposure in Thousands 55 50 After 5 years of instruction 47,450 hrs. 45 CALP 40 Native English Speaker (L1) -24,000 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EXPOSURE Awake 12 Age 0 to 5: Formal instruction begins Asleep 12 35 30 365days x 12hrs. x 5yrs.= 21,900 hrs 10 25 365days x 14hrs. x 5yrs.= 25,550 +21,900 47,450 20 Limited English Speaker (L2) 15 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EXPOSURE 10 Age 5 to 10+: 14 23, 725 hrs. 21,900 hrs. -18,000 Native (L1) English(L2) Age 0 to 5: 10 2 5 3,650 hrs. 365days x 2hrs. x 5yrs. = 3,650 hrs. Age 5 to 10+ 3 11 365days x 11hrs. x 5yrs.= 20,075 +3,650 23,725 B 1 2 3 4 5 K 6 1 st 7 2 nd 8 3 rd Age and Grade Level 9 4 th 10 5 th 11 6 th 12 7 th 13 8 th 14 9 th Achievement Trajectories for ELLs: Native language makes a difference. General Pattern of Bilingual Education Student Achievement on Standardized Tests in English 60 The “Slavin” window *Note 1 40 52(54)* Late-exit bilingual and content ESL 30 40(32)* Early-exit bilingual and content ESL 20 34(22)* Content-based ESL 24(11)* ESL pullout traditional 10 The achievement “gap” The “Closing” window 0 Normal Curve Equivalents 50 61(70)* Two-way bilingual K 2 The “English-only” window 4 6 8 10 12 Grade Level *Note 1: Average performance of native-English speakers making one year's progress in each grade. Scores in parentheses are percentile ranks converted from NCEs. Adapted from: Thomas, W. & Collier, V. (1997). Language Minority Student Achievement and Program Effectiveness. Washington DC: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. Achievement Trajectories for ELLs: Students at-risk for failure. 60 General Pattern of Bilingual Education Student Achievement on Standardized Tests in English *Note 1 40 52(54)* Late-exit bilingual and content ESL 30 40(32)* Early-exit bilingual and content ESL 20 34(22)* Content-based ESL 10 24(11)* ESL pullout traditional 0 Normal Curve Equivalents 50 61(70)* Two-way bilingual K 2 4 6 8 10 12 Grade Level *Note 1: Average performance of native-English speakers making one year's progress in each grade. Scores in parentheses are percentile ranks converted from NCEs. Adapted from: Thomas, W. & Collier, V. (1997). Language Minority Student Achievement and Program Effectiveness. Washington DC: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. Model Comparison of Percentage of "At-Risk" Second Language Students BLUE LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for ESL students 6% RED LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for monolingual English students 14% 50 70 84 16 98 2 >99 <1 -3SD -2SD -1SD X +1SD +2SD +3SD 14% 6% Two way bilingual (dual immersion) – 6% At-Risk Model Comparison of Percentage of "At-Risk" Second Language Students BLUE LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for ESL students RED LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for monolingual English students 11% 14% 50 54 84 16 98 2 >99 <1 -3SD -2SD -1SD X +1SD +2SD +3SD 14% 11% Late exit bilingual and content based ESL – 11% At-Risk Model Comparison of Percentage of "At-Risk" Second Language Students BLUE LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for ESL students 27% RED LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for monolingual English students 14% 32 50 84 16 98 2 >99 <1 -3SD -2SD -1SD X +1SD +2SD +3SD 14% 27% Early exit bilingual program with content ESL – 27% At-Risk Model Comparison of Percentage of "At-Risk" Second Language Students BLUE LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for ESL students 41% 14% 22 50 RED LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for monolingual English students 84 16 98 2 >99 <1 -3SD -2SD -1SD X +1SD +2SD 14% 41% Content-based ESL support only – 41% At-Risk +3SD Model Comparison of Percentage of "At-Risk" Second Language Students BLUE LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for ESL students 60% 14% 11 50 RED LINE = Distribution of achievement scores for monolingual English students 84 16 38% 98 2 >99 <1 -3SD -2SD -1SD 14% X +1SD +2SD +3SD IQ 100-105 60% Traditional (non-content) ESL pullout support only – 60% At-Risk Implications of Early Language Differences on Academic Achievement The ELL Achievement Gap “On the 2007 National Assessment of Educational Progress, fourth-grade ELLs scored 36 points below non-ELLs in reading and 25 points below non-ELLs in math. The gaps among eighth-graders were even larger—42 points in reading and 37 points in math.” Source: Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. American Educator, 32 (2) pp. 8-23, 42-44. Implications of Early Language Differences on Academic Achievement 52 points 42 points 285 265 45 points 41 points 245 Non-ELL 30 points 225 ELL 31 points 205 185 Grade 4 Grade 8 Grade 12 2004 Grade 4 Grade 8 Grade 12 2008 Results of NAEP Data on Reading Achievement for ELL vs. Non-ELL Developmental Implications of Early Language Differences on the Acquisition of Reading and Writing Skills • Reading (and writing) are symbolic aspects of language development. • Best predictors of reading acquisition and achievement are Ga (primarily phonological awareness) and Gc (primarily vocabulary) • Best approach to teaching reading is through a balanced literacy program that is based on both a phonological approach (sounding out words) and sight word development (recognizing words immediately—orthographic structure) • Because language acquisition is a developmental process, subject to the maturation patterns of the brain, so too is reading acquisition in any language at the mercy of how the brain develops. Source: Feifer, S. G. & De Fina, P. A. (2000). The Neuropsychology of Reading Disorders: Diagnosis and Intervention. Middletown, MD: School Neuropsych Press. Developmental Implications of Early Language Differences on the Acquisition of Reading Skills Characteristics of Impaired Readers Poor decoding skills – Characteristics of Normal Bilinguals Poor decoding skills in older bilinguals – Suggests intrinsic difficulty in phonological processing Possible circumstantial issue if sounds were not heard in early childhood, otherwise minimal effect related to limited exposure Weak vocabulary development – Weak vocabulary development – Suggests intrinsic difficulty despite adequate language exposure Circumstantial issue due to lack of comparable exposure to English Inability to read strategically (can’t rely on Gf) – Inability to read strategically (can’t rely on Gf) – Suggests intrinsic problem in fluid reasoning Circumstantial issue due to limited educational benefit and CALP Poor spelling – Good spelling – Suggests intrinsic problem in visual memory Assumes no intrinsic problems in visual memory Many reading opportunities outside of school – Few reading opportunities outside of school – Available but insufficient to markedly improve reading skills Insufficient to markedly improve reading skills even if available Poor motivation and confidence – Poor motivation and confidence – Tendency to avoid reading as it becomes effortful and difficult Tendency to avoid reading as it becomes effortful and difficult Adapted from: Ortiz, S. O., Douglas, S. & Feifer, S. G. (2013). Bilingualism and Written Expression: A neuropsychological perspective. In S. G. Feifer (Ed.) The Neuropsychology of Written Language Disorders: A framework for effective interventions (pp. 113-130). Middletown, MD: School Neuropsych Press Developmental Implications of Early Language Differences on the Acquisition of Reading Skills Subtypes of Dyslexia Implications for Normal Bilinguals Dysphonetic Dyslexia - difficulty in using phonological route in reading, so visual route to lexicon is used. Little reliance on letter-to-letter sound conversion. Over-reliance on visual cues to determine meaning from print. Not usually evident in young bilinguals. However, difficulties may be evident if an individual is past the critical period (10-12 y/o) when first hearing sounds of a new language. Neuronal pruning creates a “wall” that limits accurate processing of new sounds. Surface Dyslexia - over-reliance on sound/symbol relationships as process of reading never becomes automatic. Words broken down to individual phonemes and read slowly and laboriously, especially where phonemes and graphemes are not in 1-to-1 correspondence. Very typical and common characteristic of bilinguals due to the lack of sufficient time and opportunity to develop automaticity and reading fluency. Insufficient orthographic development means reading remains an auditory process that may never become automatic and transparent. Mixed Dyslexia - Severely impaired readers with characteristics of both phonological deficits as well as visual/spatial deficits. Have no usable key to reading or spelling code. Bizarre error patterns observed. Not usually evident in bilinguals, although, the need to over-rely on visual processing to access meaning limits development of reading speed and automaticity. However, significant difficulties may be evident if an individual is past the critical period (10-12 y/o) and has had limited or no prior education in reading. Reading Comprehension Difficulties - inability to apply strategies to derive meaning from print. Deficiencies in working memory common and vocabulary development may lag behind peers. Very typical and common characteristic of bilinguals when native language development is absent, interrupted or insufficient to promote age or grade expected CALP. Limited exposure to instructional language causes the curriculum to exceed the individual’s development in vocabulary and abstract/reasoning abilities to foster meaning. Table adapted from: Ortiz, S. O., Douglas, S. & Feifer, S. G. (2013). Bilingualism and Written Expression: A neuropsychological perspective. In S. G. Feifer (Ed.) The Neuropsychology of Written Language Disorders: A framework for effective interventions (pp. 113-130). Middletown, MD: School Neuropsych Press Is Special Education the Answer? Special education cannot solve problems that are rooted in general education. Is Special Education the Answer? OCR Surveys and National Trends in Disproportionality OCR Surveys Conducted every 2 years 1978 – 2010: ◦ African Americans continue to be over-represented as: ID and ED 1980 – 2010: ◦ Hispanics continue to be overrepresented as: LD, SLI and ID National Trends ◦ African American identification increasing in: ID, ED, and LD ◦ Hispanic identification increasing in: LD and SLI ◦ Native American identification increasing in: ID, ED and LD Effective Instruction for ELLs: What the Research Says Typical English Learners who begin school 30 NCE’s behind their native English speaking peers in achievement, are expected to learn at: “…an average of about one-and-a-half years’ progress in the next six consecutive years (for a total of nine years’ progress in six years--a 30-NCE gain, from the 20th to the 50th NCE) to reach the same long-term performance level that a typical nativeEnglish speaker…staying at the 50th NCE) (p. 46). In other words, they must make 15 months of academic progress in each 10 month school year for six straight years—they must learn 1½ times faster than normal. Source: Thomas, W. & Collier, V. (1997). Language Minority Student Achievement and Program Effectiveness. Washington DC: NCBE. Effective Instruction for ELLs: What the Research Says Of the five major, meta-analyses conducted on the education of ELLs, ALL five came to the very same conclusion: “Teaching students to read in their first language [i.e., bilingual education] promotes higher levels of reading achievement in English” (p. 14, 2008). “Bilingual education [i.e., teaching students to read in their first language] produced superior reading outcomes in English compared with English immersion” (p. 9, 2013). This is true primarily because teaching in the native language does not interrupt or inhibit the linguistic and cognitive development that students bring to school. Sources: Goldenberg, C. (2013). Unlocking the Research on English Learners: What we know—and don’t know—about effective instruction. American Educator, 37,(2), pp. 4-11, 38-39. and Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. American Educator, 32 (2) pp. 8-23, 42-44. The “Basics” of Effective Instruction and Intervention Strategies for English Language Learners 1. Provide comprehensible input and output • Students need to understand what they are told as well as what they say 2. Negotiate meaning • Connect what is being taught with why it’s important and meaningful 3. Shelter the core/content instruction • Provide necessary support to maintain the student’s access to core subjects 4. Develop thinking skills and strategies for learning • Sometimes students need to be taught explicitly how to learn 5. Give appropriate error correction • Correct only the most egregious errors, not every one of them 6. Control classroom climate • If students do not feel comfortable and safe, they will shut down Linking Assessment to Responsive Intervention • The value of the heritage language (L1) in being able to facilitate learning is too valuable to be ignored and the potential of bilingualism for improving academic progress, response-to-intervention, and testing, is necessary now more than ever. • Merely teaching English learners to speak and comprehend English may comply with Title I and III of ESEA (aka NCLB) but is insufficient to foster academic success for the large majority of students. • Of the three major variables in learning (language, cognition, curriculum) only the curriculum is within our control. To improve learning we must not attempt to fit the child to the curriculum but rather, fit the curriculum to the child. • Political ideology or knee-jerk psychology about bilingualism and schooling cannot continue to be used as the basis for instruction of ELLs. The research is very clear, the longer children are taught in their native language, the better they succeed in English. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: What the research says about effective Instruction for ELLs Application of RTI with ELLs raises numerous questions regarding the process, goals, intentions, and definitions. For example: What constitutes sufficient “opportunity to learn” for ELLs?” What works for ELLs, and with what type of ELLs? What actually makes an intervention culturally or linguistically appropriate? How will ELLs “catch up” on experiential vs. discrete skills and abilities? What research guides expectations of progress or rates of acquisition that define success or failure to respond to intervention? How does RTI measure up to the “Standards” and IDEA requirements for educational evaluation, particularly as related to SLD? Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: What the research says about effective Instruction for ELLs Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: What the research says about effective Instruction for ELLs Typical English Learners who begin school 30 NCE’s behind their native English speaking peers in achievement, are expected to learn at: “…an average of about one-and-a-half years’ progress in the next six consecutive years (for a total of nine years’ progress in six years--a 30-NCE gain, from the 20th to the 50th NCE) to reach the same long-term performance level that a typical nativeEnglish speaker…staying at the 50th NCE) (p. 46). In other words, they must make 15 months of academic progress in each 10 month school year for six straight years—they must learn 1½ times faster than normal. Source: Thomas, W. & Collier, V. (1997). Language Minority Student Achievement and Program Effectiveness. Washington DC: NCBE. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS Assessments, including RTI, should be selected and administered so as not to be discriminatory on a racial or cultural basis. The use of RTI, as with any assessment tool or procedure, should be designed to reduce threats to the reliability and validity of inferences that may arise from language (and cultural) differences. Is RTI inherently more “fair” than other methods of evaluation, in particular, standardized testing? Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS The misguided and incorrect view that IQ=Ability=Potential, coupled with the equally flawed notion of abilityachievement discrepancy as an infallible marker of SLD, has made all of us wary of intellectual and cognitive testing; especially in those cases where testing is seen only as a process for uncovering a person’s general intelligence, global intellectual ability, or innate “potential” for success. “We are concerned that if we do not engage in dialogue about how culture mediates learning, RTI models will simply be like old wine in a new bottle, in other words, another deficit-based approach to sorting children, particularly children from marginalized communities.” NCCRESt Position Statement 2005 Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS • Baker & Good (1995) investigated the reliability, validity, and sensitivity of English CBM passages with bilingual Hispanic students and concluded that it was as reliable and valid for them as for native English speakers despite the presence of differential growth rates. • Gersten & Woodward (1994) suggested that CBM could be used to develop growth rates for ELL students, but erroneously concluded that ELL students generally continue to make academic progress toward grade-level norms whereas ELL students with LD do not. Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS In describing a basic three-tier RTI model, one of the stated potential benefits included: “Increased fairness in the assessment process, particularly for minority students” Kovaleski & Prasse, 2004 Although it has long been assumed that RTI will benefit ELLs by avoiding the types of biases associated with standardized testing, this premise does not appear to be wholly supported by research. Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 1 Issues Tier 1 RTI evaluation implications for ELLs: Determine whether effective instruction is in place for groups of students “Teaching ELLs to read in their first language and then in their second language, or in their first and second languages simultaneously (at different times during the day), compared with teaching them to read in their second language only, boosts their reading achievement in the second language” (emphasis in original). “The NLP was the latest of five meta-analyses that reached the same conclusion: learning to read in the home language promotes reading achievement in the second language.” Source: Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. American Educator, 32 (2) pp. 8-23, 42-44. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention Tier 1 goals are very noble and represent a strong commitment to all children. However, when it comes to ELLs, the question regarding what constitutes “quality” academic instruction and support tends to be overlooked in the most general sense. The Language Proficiency-Academic Performance Continuum Level 1 2 3 4 5 How will they gain language? What do they Understand? What can they do? Can be silent for an initial period; Recognizes basic vocabulary and high frequency words; May begin to speak with few words or imitate Learner Characteristics Multiple repetitions of language; Simple sentences; Practice with partners; Use visual and realia, Model, model, model; Check for understanding; Build on cultural and linguistic history Instructions such as: Listen, Line up, Point to, List, Say, Repeat, Color, Tell, Touch, Circle, Draw, Match, Label Use gestures; Use other native speakers ; Use high frequency phrases; Use common nouns; Communicate basic needs; Use survival language (i.e., words and phrases needed for basic daily tasks and routines) Understand phrases and short sentences; Beginning to use general vocabulary and everyday expressions; Grammatical forms may include present, present progress and imperative Increased comprehension in context; May sound proficient but has social NOT academic language; Inconsistent use of standard grammatical structures Very good comprehension; More complex speech and with fewer errors; Engages in conversation on a variety of topics and skills; Can manipulate language to represent their thinking but may have difficulty with abstract academic concepts; Continues to need academic language development Multiple repetitions of language; Visual supports Present and past tense; School for vocabulary; Pre-teach content vocabulary; related topics; Comparatives & Link to prior knowledge superlatives; Routine questions; Imperative tense; Simple sequence words Routine expressions; Simple phrases; Subject verb agreement; Ask for help Multiple repetitions of language; Use synonyms and antonyms; Use word banks; Demonstrate simple sentences; Link to prior knowledge Formulate questions; Compound sentences; Use precise adjectives; Use synonyms; Expanded responses Communicates effectively on a wide range of topics; Participates fully in all content areas at grade level but may still require curricular adjustments; Comprehends concrete and abstract concepts; Produces extended interactions to a variety of audiences May not be fully English proficient in all Analyze, Defend, Debate, Predict, domains (i.e., reading, writing, speaking, Evaluate, Justify, Hypothesize and listening); Has mastered formal and informal Synthesize, Restate, Critique language conventions; Multiple opportunities to practice complex grammatical forms; Meaningful opportunities to engage in conversations; Explicit instruction in the smaller details of English usage; Focus on “gaps” or areas still needing instruction in English; Focus on comprehension instruction in all language domains Multiple repetitions of language; Authentic practice opportunities to develop fluency and automaticity in communication; Explicit instruction in the use of language; Specific feedback; Continued vocabulary development in all content areas Past progressive tense; Contractions; Auxiliary verbs/verb phrases; Basic idioms; General meaning; Relationship between words Present/perfect continuous; General & implied meaning; Varied sentences; Figurative language; Connecting ideas; Tag questions Range of purposes; Increased cultural competence (USA); Standard grammar; Solicit information May not yet be fully proficient across all domains; Comprehends concrete and abstract topics; Communicates effectively on a wide range of topics and purposes; Produces extended interactions to a variety of audiences; Participates fully in all content areas at grade level but may still require curricular modifications; Increasing understanding of meaning, including figurative language; Read grade level text with academic language support; Support their own point of view; Use humor in native-like way Source: Turner & Brown, (2012) as cited in Brown, J. E. & Ortiz, S. O. (2014). Interventions for English Learners with Learning Difficulties. In J. T. Mascolo, V. C. Alfonso, and D. P. Flanagan (Eds.), Essentials of Planning, Selecting, and Tailoring Interventions for Unique Learners (pp. 267-313)., Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons. PLUSS Framework for Evidence-based Instruction for ELLs PLUSS Framework Pre-teach critical vocabulary Language modeling and opportunities for practice Use visuals and graphic organizers Systematic and explicit instruction Strategic use of native language & teaching for transfer Definition Evidence Presentation of critical vocabulary prior to lessons to ensure later Beck, McKeown and Kucan (2002); Heibert and comprehension using direct instruction, modeling, and Lubliner (2008); Martinez and Lesaux (2011); Nagy, connections to native language Garcia, Dyrgunoglu and Hancin (1993) Teacher models appropriate use of academic language, then Dutro and Moran (2003); Echevarria, Vogt and Short provides structured opportunities for students to practice using (2008); Gibbons (2009); Linan-Thompson and the language in meaningful contexts Vaughn (2007); Scarcella (2003) Strategically use pictures, graphic organizers, gestures, realia, and Brechtal (2001); Echevarria and Graves (1998); other visual prompts to help make critical language, concepts, and Haager and Klingner (2005); Linan-Thompson and strategies more comprehensible to learners Vaughn (2007); O’Malley and Chamot, (1990) Explain, model, provide guided practice with feedback, and Calderón (2007); Flagella-Luby and Deshler (2008); opportunities for independent practice in content, strategies, and Gibbons (2009); Haager and Klingner (2005); Klingner concepts and Vaughn (2000); Watkins and Slocum (2004) Identify concepts and content students already know in their Carlisle, Beeman, Davis and Spharim (1999); native language and culture to explicitly explain, define, and help Durgunoglu, et al. (1993); Genesee, Geva, Dressler, them understand new language and concepts in English and Kamil (2006); Odlin (1989); Schecter and Bayley (2002) Source: NCCRESt, (2012) as reprinted in Brown, J. E. & Ortiz, S. O. (2014). Interventions for English Learners with Learning Difficulties. In J. T. Mascolo, V. C. Alfonso, and D. P. Flanagan (Eds.), Essentials of Planning, Selecting, and Tailoring Interventions for Unique Learners (pp. 267-313)., Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons. Examples of PLUSS Framework Applied in the Classroom PLUSS Framework Example Pre-teach critical Select 3-5 high utility vocabulary words crucial to understanding text (not necessarily content specific words) and vocabulary use the words over time (Honig, Diamond, & Gutlohn, 2008; Beck, McKeown, Kucan, 2002) Language modeling and Provide language frames and sentence starters to structure language interaction. For example, after having defined the opportunities for you were preoccupied.” (pause to give time to think). “Turn to your partners and share, starting your sentence with, ‘I practicing was preoccupied when…’, what will you start your sentence with?” (Have students repeat the sentence starter before explicitly teach student friendly definitions, model using the words, and provide students with repeated opportunities to word, “preoccupied,” for instance, ask students to use the word, “preoccupied,” in a sentence, “Think of a time when turning to their neighbor and sharing). Use visuals and graphic Consistently use a Venn diagram to teach concepts, such as compare and contrast, and use realia and pictures to support the teaching of concepts (Echevarría, Vogt, & Short, 2008) organizers Systematic and explicit Teach strategies like summarization, monitoring and clarifying, and decoding strategies through direct explanation, modeling, guided practice with feedback, and opportunities for application (Honig, Diamond, & Gutlohn, 2008). instruction Strategic use of native Use native language to teach cognates (e.g., teach that preoccupied means the same thing as preocupado in Spanish) or explain/clarify a concept in the native language before or while teaching it in English. language & teaching for transfer Source: Brown, J. E. & Ortiz, S. O. (2014). Interventions for English Learners with Learning Difficulties. In J. T. Mascolo, V. C. Alfonso, and D. P. Flanagan (Eds.), Essentials of Planning, Selecting, and Tailoring Interventions for Unique Learners (pp. 267-313)., Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention Dual-language/dual immersion and maintenance type bilingual programs probably meet this criterion. But what about students in transitional bilingual, ESL content, ESL pullout, and English immersion programs? Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: What the research says about effective Instruction for ELLs Of the five major, meta-analyses conducted on the education of ELLs, ALL five came to the very same conclusion: “Teaching students to read in their first language [i.e., bilingual education] promotes higher levels of reading achievement in English” (p. 14, 2008). “Bilingual education [i.e., teaching students to read in their first language] produced superior reading outcomes in English compared with English immersion” (p. 9, 2013). This is true primarily because teaching in the native language does not interrupt or inhibit the linguistic and cognitive development that students bring to school. Sources: Goldenberg, C. (2013). Unlocking the Research on English Learners: What we know—and don’t know—about effective instruction. American Educator, 37,(2), pp. 4-11, 38-39. and Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners: What the research does—and does not—say. American Educator, 32 (2) pp. 8-23, 42-44. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: What the research says about effective Instruction for ELLs 52 points 42 points 285 265 45 points 41 points 245 Non-ELL 225 ELL 30 points 31 points 205 185 Grade 4 Grade 8 Grade 12 2004 Grade 4 Grade 8 Grade 12 2008 Results of NAEP Data on Reading Achievement for ELL vs. Non-ELL Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 1 Issues How can RTI-based evaluation be fair when the instructional programs most often used to instruct groups of ELL students (i.e., ESL, English immersion) have been demonstrated empirically to be ineffective in promoting grade level achievement or academic success? Well designed and effective interventions cannot make up for deficiencies in educational pedagogy or artifactual developmental delays that result from the unenlightened use of “intuitive science” (i.e., common sense) or application of misguided political ideology. What would you choose? SCHOOL ENROLLMENT FORM Please select an instructional program for your child by placing a check in the appropriate box below: English as a Second Language SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: This program has been scientifically validated to lower achievement in English, increase special education placement, raise the risk of dropping out, and decrease rates of graduation. Bilingual Education Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 2 Issues Tier 2 RTI evaluation implications for ELLs: Provide effective instruction to the target student and measure its effect on performance “Making an assumption that what works with native English speakers will work with students from diverse language backgrounds may be inaccurate (McLaughlin, 1992). Although substantial empirical support exists for the use of a response-to-intervention (RTI) approach to address literacy problems with native English speakers (e.g., Burns, Appleton, and Stehouwer, 2005; Mathes et al., 2005; Vellutino, Scanlon, and Tanzman, 1998), very little data exist about the effectiveness of this approach with EL learners (Vaughn et al., 2006).” Source: Vanderwood, M. L. & Nam, J. E. (2007). Response to Intervention for English Language Learners: Current developments and future directions. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns and A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of Response to Intervention: The Science and Practice of Assessment and Intervention (pp. 408-417). What Works Clearinghouse Looks at Reading Recovery® for English Language Learners The WWC examined the research conducted in English on Reading Recovery® and identified 13 studies that were published or released between 1997 and 2008 that looked at the effectiveness of this short-term tutoring intervention on English language learners' literacy skills. None of these studies meet WWC evidence standards. Therefore, conclusions may not be drawn based on studies conducted in English about the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of Reading Recovery® for English Language Learners. December 15, 2009 Full report available at: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/reports/english_lang/read_recov/ What Works Clearinghouse Looks at “Accelerated Reader” for English Language Learners The WWC examined the research on "Accelerated Reader" and identified 13 studies that were published or released between 1983 and 2008 that looked at the effectiveness of this curriculum on English language learners’ reading and math skills. None of these studies meet WWC evidence standards. Therefore, conclusions may not be drawn based on research about the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of "Accelerated Reader" on English Language Learners. December 22, 2009 Full report available at: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/reports/english_lang/accreader/ Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 2 Issues How can RTI-based evaluation be fair to the individual student if the program used to instruct that student (i.e., ESL, English immersion) has been demonstrated empirically to be ineffective in promoting grade level achievement or academic success? Even after an ELL has been exited from or deemed to no longer need or require bilingual education or ESL services (un-LEP’d), it cannot be assumed that he/she is comparable to age or grade matched monolingual English speaking peers, or that interventions that “work” for native English speakers will now suddenly “work” just as well for non-native English speakers. Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 3 Issues Tier 3 RTI evaluation implications for ELLs: Refer students whose RTI warrants additional or intensive continuing interventions What exactly will evaluation look like beyond progress monitoring and curriculum based assessment of current academic skills? How will these procedures systematically evaluate the influence of cultural and linguistic differences and the extent to which they are primarily responsible for lack of progress as compared to lack of progress due to a learning disability, particularly when RTI has not ensured that evidence-based instruction (i.e., in the native language) has been provided? Source: Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., Alfonso, V. C. & Dynda, A. M. (2006). Integration of Response to Intervention and Norm-Referenced Tests in Learning Disability Identification: Learning from the Tower of Babel. Psychology in the Schools, Vol. 43(7), 807-825. Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 3 Issues The assumption of comparable levels of “effective instruction” across type of ESL or bilingual program is unlikely to ever to be met. A student may have one type of program in one classroom or in one school and a different one in another classroom or school. Thus, the nature and implementation of various native language programs as well as any school movement complicates reliable, valid, and fair measurement of progress within the curriculum. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention Is this really an example of “not making progress” for an ELL student who is receiving ESL services only? Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention To what extent do Isiah, Mary, and Amy represent “true” peers for Chase? ELLs must be compared to other ELLs who have similar educational experiences AND similar levels of English language proficiency. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention To what extent did Fuchs et al. base growth rates on ELLs of comparable educational experiences AND English language proficiency? Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention To what extent do the gains by the “peers cohort” represent the expected gains for ELLs who may differ in terms of educational experiences AND English language proficiency? Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 3 Issues The most common type of instruction given in schools today, ESL, creates an artifactual linguistic “handicap” that puts otherwise capable children at levels far below their age and grade related peers in school achievement. What is “effective instruction” for the average 3rd grader may be totally inappropriate for the average ELL who, nonetheless is in 3rd grade. ELLs are clearly able to make progress comparable to English speaking peers on discrete types of skills (e.g., phonological processing or phonemic awareness). However, progress on other abilities that develop as a function of age and experience (e.g., vocabulary, advanced grammar), is likely to remain behind that of peers. Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 3 Issues Classroom or Grade Level Aim Line 6 week standard 12 week standard 50 WRCPM 50 WRCPM = Number of Egberto’s progress if he makes gains comparable to English speaking peers 45 Words Read 15 word difference 40 Correctly Per Minute 35 WRCPM 35 30 Egberto’s progress if he makes gains comparable to other “proficient” ELLs 25 word difference 25 Classroom/grade level expectations = 15 15 word difference 20 a 6 week period 20 word difference 15 10 25 word difference English learners often begin behind Egberto’s progress if he doesn’t make gains comparable to other “proficient” ELLs 35 word difference WRCPM progress over 5 English speakers Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Example 2nd Grade Progress Monitoring Chart *Note: The name,“Egberto,” is a derivative of “Egbert” and used with the blessings of Dan Reschley. 11 12 13 14 Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 3 Issues Unless measurement methods used in RTI, whether CBM or otherwise, account for the differential rates of development that are occurring in the processes related to native language acquisition, English acquisition, and acculturation to the mainstream, there is no guarantee that results will be any more “fair” than other methods. Unless otherwise indicated, the information in this packet is © Samuel O. Ortiz, Ph.D. and S. Hector Ochoa, Ph.D. May not be reproduced without permission. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention It is important to recognize that RTI, just like testing, is a measurement paradigm. RTI is a different paradigm than testing, but measurement and comparisons of the collected measurements against a pre-determined standard is still at the very core of RTI. Nondiscriminatory Assessment and RTI: Issues in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Intervention What about students that speak languages other than Spanish? Fairness in Evaluation of ELLs via RTI/MTSS: Tier 3 Issues Once an ELL has been exited from or deemed to no longer need or require bilingual education or ESL services (i.e., they have been FLEP’d, or unLEP’d), it cannot be assumed that they are comparable in terms of their academic achievement to their monolingual English speaking peers. ELLs will invariably continue to have increasingly less foundation and lifelong experiences in English language development and in then acquisition of the acculturative knowledge that is embedded within and underlies the subject matter of all curricula and for which mastery remains a critical requirement for success in school. “Once a bilingual, always a bilingual.” ELLs do not suddenly cease to be bilingual simply because they have become proficient and dominant in English. Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs “Instead of attempting to describe each individual’s mental endowment by a single index such as a mental age or an intelligence quotient, it is preferable to describe him in terms of a profile of all the primary factors which are known to be significant…If anyone insists on having a single index such as an IQ, it can be obtained by taking an average of all the known abilities. But such an index tends so to blur the description of each man that his mental assets and limitations are buried in the single index” (Thurstone, 1946, p. 110). Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs Cognitive testing and RTI are not mutually exclusive. Both are measurement paradigms but each answers a different and important question. RTI seeks to ensure that the learning difficulties are not the result of extrinsic issues in teaching, instruction, curriculum, etc. It addresses the question of learning needs and measures the individual’s success when those needs are identified and met. It is not a diagnostic system and is best utilized for understanding academic development as compared to peers on a local basis (e.g., classroom, school, or district). Cognitive testing, particularly within a PSW model, seeks to provide insight into any possible intrinsic factors that may be responsible for learning difficulties and which inhibit the acquisition and development of academic skills. It is a diagnostic system and is best utilized in understanding cognitive development as compared to peers on a national basis (e.g., all individuals of the same age or grade). In the same manner that low test scores do not automatically indicate a learning disability, so too does poor progress or a failure to respond to intervention also not invariably suggest a learning disability. In both cases there are an infinite number of reasons that account for and may explain the observed problematic performance; only one of which is a disability. Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs “The danger with not paying attention to individual differences is that we will repeat the current practice of simple assessments in curricular materials to evaluate a complex learning process and to plan for interventions with children and adolescents with markedly different needs and learning profiles” (p. 567; Semrud-Clikeman, 2005). Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs Understanding the relationship between cognitive abilities and academic skills provides a new window into explanations for learning difficulties as well as new avenues for tailoring intervention to increase success. Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs Because RTI is usually in place as part of a pre-referral system, students who reach Tier 3 may benefit from comprehensive testing to assess their cognitive strengths and weaknesses, particularly in service of SLD identification via a PSW approach. The IDEA definition remains as follows: Specific Learning Disability (a) In general. The term 'specific learning disability' means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which disorder may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations. (b) Disorders included. Such term includes such conditions as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia.“ (c) Disorders not included. Such term does not include a learning problem that is primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of mental retardation, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage." Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs Old notions about lack of aptitude x treatment interaction are predicated upon educational ideas regarding learning “styles” whereas modern research and theory (e.g., CHC theory) provide empirically supported causal explanations regarding the relationship between various cognitive abilities and the acquisition and development of academic skills. Perhaps the best example of this research is the link between auditory processing (Ga) skills, specifically phonological awareness and the acquisition of basic reading skills. Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs Knowledge that a student has a particular deficit (e.g., working memory) is valuable, not only because it provides clear support for the statutory definition of SLD in IDEA, but also because it helps determine whether an observed failure to respond was due to instructional over-reliance in the individual’s area of weaknesses. If so, efforts for intervention can be significantly improved by selecting programs that minimize use of abilities that are weak for the individual, rather than continuing to select them randomly, and which will increase the likelihood that the individual will demonstrate better progress and more efficient learning. Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs In turn, testing benefits from information gathered over the course of the previous two tiers including because it provides a detailed and comprehensive context within which the student’s performance in various areas of cognitive functioning that are crucial to the acquisition and development of academic skills. Such data and information includes: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Attendance and experience with school setting Match between child’s L1 and language of instruction Parent’s ability to support language of instruction Years (duration) of instruction in L1 and L2 Quality of L1/L2 instruction or bilingual program Cultural relevance of the curriculum Consistency in curriculum and instructional programs Teaching strategies, styles, attitudes, and flexibility System and individual expectations regarding dual language learners Direct observation of classroom performance and learning An Hypothesis Testing CHC Model for SLD Identification Within an RTI Framework Use of an hypothesis-testing approach to SLD evaluation helps to ensure that appropriate questions are asked at each respective level so that the necessary data are collected and interpreted in light of the individual needs of the learner. Such an approach avoids the typical exploratory type of evaluation that is often subject to confirmatory bias.” (p. 746) Source: Flanagan, Fiorello & Ortiz (2010). Integrating RTI and Cognitive Testing for ELLs Matching Standardized Treatment Protocols (STP) with Specific Areas of Weakness Effective Instruction for ELLs: Match the development. • Don’t be afraid to provide the cognitively-linguistically appropriate level of instruction regardless of current AGE or GRADE. • Teach within the zone of proximal development, essentially what comes NEXT because instruction that is beyond what comes “NEXT” will be ineffective and impede development even further. • Don’t try to alter cognitive or linguistic development because you CAN’T. Alter the curriculum, because you CAN. • Provide access to core curriculum and focus on developing thinking and literacy skills from the CURRENT developmental level. • Use meta-cognitive strategies that help students think about, plan, monitor, and evaluate learning at their CURRENT level. • Use cognitive strategies that help engage students in the learning process and which involve interacting with or manipulating the material mentally or physically, and applying a specific technique to learning tasks at their CURRENT developmental level. • Use social-affective strategies that help students interact with another person, accomplish a task, or that assist in learning. LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT Prior Learning Proximal Learning Future Learning Independent Performance (“known”) Assisted Performance (“with help”) Beyond Performance (“can’t do”) Appropriate level of instruction Summary of Instructional and Intervention Strategies for English Language Learners 1. Instruction must always match linguistic/cognitive development regardless of the individual’s age or grade. 2. No amount or type of instruction can make up for developmental delays that occur as a function of differences in the primary language and the language of instruction. 3. Individual differences means that some children will succeed despite the way we instruct them and many will fail because of the way we instruct them. 4. There is no single teaching method or intervention that is appropriate for all English language learners. 5. There is no single teaching method or intervention that will help all English learners “catch up.” 6. Of the three major variables for learning, language, cognition, and academic development, only the latter is within our control. Thus, to improve learning we must not attempt to fit the child to the curriculum but rather, fit the curriculum to the child. Any other way will not prove successful. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Formal and Informal Learning Experiences Children raised in two cultures naturally split their time and experience across each of them. Unfortunately, parents are usually able to mediate aspects of only their native culture to their children and cannot do so with the new culture because of their own lack of familiarity with it. This means that children from bilingual-bicultural backgrounds must often navigate both the new language and culture almost on their own, a term I refer to as “cultural pioneering.” The process of learning a new language and culture thus becomes very dependent on the experiences a child has, particularly while in school. If something is not explicitly taught in school, the chances that it may be taught and learned informally outside the school decrease. This often results in hit-or-miss learning that although occurs for children in general, becomes a much more frequent occurrence for children from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Areas that are highly susceptible to this influence include cultural knowledge, especially the subtle, idiosyncratic, and less frequent aspects of it as well as language, particularly correct grammar, pronunciation, usage, and pragmatics including idioms and humor. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Formal and Informal Learning Experiences Old Bay and Michigan Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Opportunity for Learning Assessment of a student's academic skills and abilities must directly examine the student's skills and abilities with respect to the actual materials and content used for instruction. Thus, authentic assessment seeks to uncover whether learning difficulties can be ascribed to experiential differences rather than ability differences. Not only does this ensure greater validity of the assessment, it provides valuable information necessary to develop specific and effective instructional strategies. In general, evidence of lack of opportunity for learning, ineffective prior instruction, and linguistically inappropriate curricula, are all factors that increase the likelihood that no disability exists. For example – According to the manual (1993) for the Nelson-Denny Reading Test, the 80 vocabulary words and their definitions were drawn from : "current, widely used high school and college texts, including words that must be known by students in order to cope successfully with school assignments." (emphasis added) Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Vocabulary Exposure and Development • It is fruitless to attempt to indoctrinate a superannuated canine with innovative maneuvers. • Scintillate, scintillate, asteroid minified. • Members of an avian species of identical plumage congregate. • Pulchritude possesses solely cutaneous profundity. • It is fruitless to become lachrymose over precipitately departed lacteal fluid. • Eschew the implement of correction and vitiate the scion. • All articles that coruscate with resplendence are not truly auriferous. • Where there are visible vapors having their prevalence in ignited carbonaceous materials, there is conflagration. • A plethora of individuals with expertise in culinary techniques vitiate the possible concoction produced by steeping certain comestibles. • Individuals who make their abodes in vitreous edifices should be advised to refrain from catapulting petrous projectiles. Homes where English is not the primary or native language results in linguistic experiences that shape the perceptions and views of the speakers particularly in reference to vocabulary but also what might constitute acceptable ways of communicating that can include comfort with basic grammatical errors, use of codeswitching, frequent use of slang or colloquial terminology, uncommon or unusual pragmatics, and variances in general language usage. Basic Writing Skills Written Expression Broad Written Lang. Math Computation Math Reasoning Broad Math Basic Rdg. Skills Rdg. Comprehension Broad Reading SS Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Academic Skills and the “Bilingual Bermuda Triangle” PR 145 99+ 130 98 115 86 100 50 85 16 70 2 55 <1 Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Classroom Behavior and Performance Characteristics and behaviors often associated with various learning problems Common manifestations of English Language Learners (ELLs) during classroom instruction that may mimic various disorders or cognitive deficits. Slow to begin tasks ELLs may have limited comprehension of the classroom language so that they are not always clear on how to properly begin tasks or what must be done in order to start them or complete them correctly. Slow to finish tasks ELLs, especially those with very limited English skills, often need to translate material from English into their native language in order to be able to work with it and then must translate it back to English in order to demonstrate it. This process extends the time for completion of time-limited tasks that may be expected in the classroom. Forgetful ELLs cannot always fully encode information as efficiently into memory as monolinguals because of their limited comprehension of the language and will often appear to be forgetful when in fact the issue relates more to their lack of proficiency with English. Inattentive ELLs may not fully understand what is being said to them in the classroom and consequently they don’t know when to pay attention or what exactly they should be paying attention to. Hyperactive Impulsive Distractible ELLs may appear to be hyperactive because they are unaware of situation-specific behavioral norms, classroom rules, and other rules of social behavior. ELLs may lack the ability to fully comprehend instructions so that they display a tendency to act impulsively in their work rather than following classroom instructions systematically. ELLs may not fully comprehend the language being being spoken in the classroom and therefore will move their attention to whatever they can comprehend appearing to be distractible in the process. Disruptive ELLs may exhibit disruptive behavior, particularly excessive talking—often with other ELLS, due to a need to try and figure out what is expected of them or to frustration about not knowing what to do or how to do it. Disorganized ELLs often display strategies and work habits that appear disorganized because they don’t comprehend instructions on how to organize or arrange materials and may never have been taught efficient learning and problem solving strategies. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Listening Comprehension and Receptive Language "I pledge a lesson to the frog of the United States of America, and to the wee puppet for witches hands. One Asian, under God, in the vestibule, with little tea and just rice for all." Source: In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson by Bette Bao Lord, © 1986, Harper Trophy. Children who are learning a second language hear and interpret sounds in a manner that conforms to words that already exist in their vocabulary. This is a natural part of the first and second language acquisition processes and should not be considered abnormal in any way. It represents the brain’s attempt to make sense and meaning of what it perceives by connecting it to what it already knows. Songs are a good example of this linguistic phenomenon even for native English speakers. Consider these classic misheard lyrics: “There’s a bathroom on the right” “Excuse me while I kiss this guy” “Doughnuts make my brown eyes blue” “Midnight after you’re wasted” Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Oral and Expressive Language 'Twas the night before Christmas, y por todo la casa, Not a creature was stirring—Caramba! Que Pasa? Los niños were tucked away in their camas, Some in camisas, some in pijamas. While hanging the medias with mucho cuidado, In hopes that old Santa would feel obligado. To bring all children, both buenos y malos, A nice batch of dulces y otros regalos. A Visit From St. Nicolas – Anonymous, 1823 Bilinguals/bicultural individuals are perfectly happy with two languages existing side by side. It provides an ability to use code switching and dual-mode communication not available to monolinguals. For bilinguals, it doesn’t matter what language is used in conversation because it all makes sense—and mutual comprehension is the goal of all language and communication. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Reading Comprehension 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe. All mimsy were the borogroves, And the mome raths outgrabe. Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll Questions: 1) What things were slithy? 2) What did the toves do in the wabe? 3) How were the borogroves? 4) What kind of raths were there? Meaning in print is not derived solely from word knowledge. Mature and advanced readers eventually discard “decoding” as the primary means for developing reading abilities in favor of orthographic processing of letters, words, sentences, and grammatical structure. Meaning is often inferred from our cultural knowledge and experience with the language. More experience equals clearer meaning and better comprehension. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Orthographic Processing BON APPETIT ARROZ Y HABICHUELAS NA ZDROWIE IUMRING TQ CQNGIUSLQNS As before, comprehension in print is not derived solely from actual word or letter identification or recognition. English is extremely irregular in morphology and mature and advanced readers eventually discard “decoding” as the primary means for developing reading abilities in favor of orthographic processing of letters, words, sentences where even small surface features are sufficient to derive meaning. Similar to grammatical structure, the ability to understand printed text in the absence of such structure, is accomplished via knowledge of the morphological rules and experience with vocabulary that comes from formal and informal sources. Comparatively speaking, ELLs have less experience and thus less ability to generate meaning automatically, fluently, or transparently. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Orthographic Processing Finished files are the result of years of scientific study combined with the the experience of years... Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Verbal and Mathematical Reasoning What day follows the day before yesterday if two days from now will be Sunday? Paul makes $25.00 a week less than the sum of what Fred and Carl together make. Carl's weekly income would be triple Steven's if he made $50.00 more a week. Paul makes $285.00 a week and Steven makes $75.00 a week. How much does Fred make? The ability to engage successfully in verbal reasoning tasks and mathematical word problems presumes the existence of a developmentally proficient level of fluency with the language since it is not the language that is being tested, but the ability to reason. When the native language development is interrupted, bilingual/bicultural individuals may not have the necessary command of the language and the task is confounded by simple comprehension issues and degrades into a test of language, not reasoning. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: Cultural Perspective and Reasoning Ability Rules: Connect all 9 dots above using only 4 straight lines. You may cross lines, but you cannot lift your pencil. Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: General Knowledge and Cultural Artifacts Cultural and Linguistic Experiences Mediate Learning: General Knowledge and Cultural Artifacts What I thought The reality Tabasco – Mexican hot sauce Made by McIlhenny Co., USA Kahlua – Hawaiian liquor Coffee liqueur made in Mexico Enfamil – Puerto Rican baby formula Made by Meade-Johnson, USA Amoco – Bilingual reference to mucous Brand of British Petroleum gas Chiclet – Mexican chewing gum Made by Cadbury/Adams, USA Toto – Strange name for a dog Dorothy’s dog’s real name Acculturation to the mainstream plays a significant role in linguistic development and learning in and out of the classroom. The presence and interaction of dual cultural contexts with which to embed certain culturally-specific words or ideas in English may lead to a failure to comprehend or acquire the true meaning of the word or the concept. Idioms are another example of this problem, for example: “I think it’s cool the way you don’t get on my case about everything.” Bottom Line - The Bilingual/Bicultural Experience Bilinguals are not two monolinguals in one head Attainment of developmental proficiency in language and acculturation is multifaceted and complex Both language acquisition and acculturation are and must be understood as developmental processes The standards by which bilinguals in U.S. public schools will always be judged will necessarily be based on the performance of individuals who are largely monolingual and monocultural Once a bilingual, always a bilingual—individuals do not suddenly cease to be bilingual/bicultural simply because they have become English dominant or English proficient Bilingual/bicultural experiences differ significantly from monolingual/monocultural ones and have important implications for schooling and learning in the classroom across the lifespan Influences on early language development can have profound and lifelong effects that are manifested in testing and evaluation Assessment of English Language Learners - Resources BOOKS: Rhodes, R., Ochoa, S. H. & Ortiz, S. O. (2005). Comprehensive Assessment of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students: A practical approach. New York: Guilford. Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S.O. & Alfonso, V.C. (2013). Essentials of Cross-Battery Assessment, Third Edition. New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc. Flanagan, D.P. & Ortiz, S.O. (2012). Essentials of Specific Learning Disability Identification. New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc. Ortiz, S. O., Flanagan, D. P. & Alfonso, V. C. (2015). Cross-Battery Assessment Software System (X-BASS v1.0). New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc. ONLINE: CHC Cross-Battery Online http://www.crossbattery.com/