http://lectureonline.cl.msu.edu/~mmp/applist/chain/chain.htm

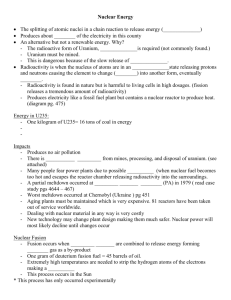

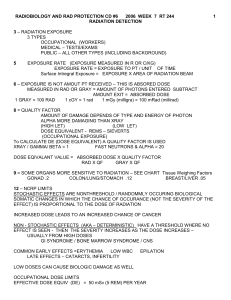

advertisement

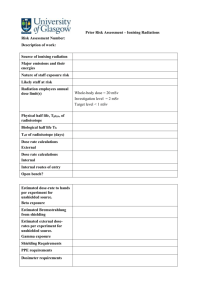

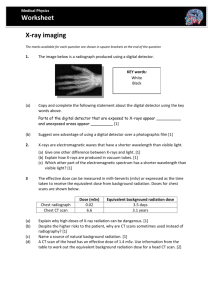

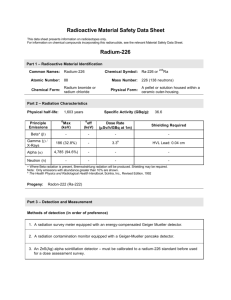

Environmental Impacts of Nuclear Technologies Bill Menke, October 19, 2005 Summary 1 radioactivity measurment 2 Neutron chain reactions 3 Environmental Issues production storage use disposal measurement Radiation: energy-carrying particles (including light) spontaneously emitted by a radioactive atom Measuring Radiation • Assessing the radioactivity of a chunk of material. Activity: Count the number of disintegrations per second. – – • Assessing the amount of energy absorbed by a chunk of material. – – – • Becquerel (Bq): Activity expressed in disintegrations per second. Curie (Ci): (An old unit) Activity expressed in equivalent grams of Radium. 1 Becquerel = 2.7 x 10-11 Curies. will depend upon both the number of particles and the energy carried by the particles emitted by the disintegrating atoms. Grays (Gy), Absorption of 1 joule (J) of radiation by 1 kg of material (for example, a human body). Rad (an old unit) 1 Gy = 100 rads Assessing the ability of radiation to damage living tissue. Must account for the fact that not all types of radiation are equally damaging. – – – X-rays and beta particles more penetrating and more damaging than alphas or neutrons. Sievert (Sv) = Grays of X-rays and beta rays + 0.10 Grays of neutrons + 0.05 Grays of alpha partcles. Rem: (an old unit), 1 Sv = 100 rems. System International (SI) Units for Radiation Quantity Unit Name (Symbol) Activity Becqueral (Bq) Disintegrations Curie (Ci) /sec 1 Bq = 2.7 x 10-11 Ci Absorbed Dose Gray (Gy) Joule/kilogram rad 1 Gy = 100 rads Dose Equivalent Sievert (Sv) Joule/kilogram rem 1 Sv = 100 rems Definition Former Unit Conversion Factor Radioactivity of some natural and other materials 1 adult human (100 Bq/kg) 7000 Bq 1 kg of coffee 1000 Bq 1 kg superphosphate fertiliser 5000 Bq The air in a 100 sq metre Australian home (radon) 3000 Bq The air in many 100 sq metre European homes (radon) 30 000 Bq 1 household smoke detector (with americium) 30 000 Bq Radioisotope for medical diagnosis 70 million Bq Radioisotope source for medical therapy 100 000 000 million Bq 1 kg 50-year old vitrified high-level nuclear waste 10 000 000 million Bq 1 luminous Exit sign (1970s) 1 000 000 million Bq 1 kg uranium 25 million Bq 1 kg uranium ore (Canadian, 15%) 25 million Bq 1 kg uranium ore (Australian, 0.3%) 500 000 Bq 1 kg low level radioactive waste 1 million Bq 1 kg of coal ash 2000 Bq 1 kg of granite 1000 Bq 10,000 mSv (10 sieverts) as a short-term and whole-body dose would cause immediate illness, such as nausea and decreased white blood cell count, and subsequent death within a few weeks. Between 2 and 10 sieverts in a short-term dose would cause severe radiation sickness with increasing likelihood that this would be fatal. 1,000 mSv (1 sievert) in a short term dose is about the threshold for causing immediate radiation sickness in a person of average physical attributes, but would be unlikely to cause death. Above 1000 mSv, severity of illness increases with dose. If doses greater than 1000 mSv occur over a long period they are less likely to have early health effects but they create a definite risk that cancer will develop many years later. Above about 100 mSv, the probability of cancer (rather than the severity of illness) increases with dose. The estimated risk of fatal cancer is 5 of every 100 persons exposed to a dose of 1000 mSv (ie. if the normal incidence of fatal cancer were 25%, this dose would increase it to 30%). 50 mSv is, conservatively, the lowest dose at which there is any evidence of cancer being caused in adults. It is also the highest dose which is allowed by regulation in any one year of occupational exposure. Dose rates greater than 50 mSv/yr arise from natural background levels in several parts of the world but do not cause any discernible harm to local populations. 20 mSv/yr averaged over 5 years is the limit for radiological personnel such as employees in the nuclear industry, uranium or mineral sands miners and hospital workers (who are all closely monitored). 10 mSv/yr is the maximum actual dose rate received by any Australian uranium miner. 3-5 mSv/yr is the typical dose rate (above background) received by uranium miners in Australia and Canada. 3 mSv/yr (approx) is the typical background radiation from natural sources in North America, including an average of almost 2 mSv/yr from radon in air. 2 mSv/yr (approx) is the typical background radiation from natural sources, including an average of 0.7 mSv/yr from radon in air. This is close to the minimum dose received by all humans anywhere on Earth. 0.3-0.6 mSv/yr is a typical range of dose rates from artificial sources of radiation, mostly medical. 0.05 mSv/yr, a very small fraction of natural background radiation, is the design target for maximum radiation at the perimeter fence of a nuclear electricity generating station. In practice the actual dose is less. Neutron chain reactions fission of atomic nucleus by neutron bombardment one neutron in, three neutrons out potential for using those neutrons to induce more fissions Leo Szilard, 1898-1964 1934: patents idea of neutron chain reaction (British patent 440,023) And nuclear reactor (patent 630726) More and more neutrons cause more and more fissions I generated these images with the applet lectureonline.cl.msu.edu/~mmp/applist/chain/chain.htm try it out! Technical Issue 1 What isotopes of what elements exhibit induced fission and release more neutrons? Only a few: U235 + n = Ba129 + Kr93 + 3n + g Note g = gamma rays As well as Pu239, U233 and Th232 but only U235 and Pu239 commonly used Technical Issue 2 Where do you get U235 and Pu239? U235 occurs naturally, and is concentrated into ores by geological processes. But it must be separated from the much more abundant U238 by a process called gaseous diffusion separation). Pu239 does not occur naturally, but can be Manufactured by bombarding U238 with neutrons in a breeder reactor. Technical Issue 3 Where do you get that first neutron? Two sources: natural, spontaneous decay releases it (bad in a bomb!) you make it in yet another nuclear reaction (eg Po210 emits a which bombards Be to release n) Technical Issue 4 Are the output neutron going the right speed to interact with more nuclei? Perhaps not. You might have to slow them down by having them interact with a moderator. Deuterium, hydrogen, boron and graphite are all good moderators. Technical Issue 5 What if too many neutrons escape from the surface of the fissionable material? The chain-reaction ceases. This always happens if the piece of material is too small, below its critical mass. To prevent this, you can: Surround the material with a reflector (e.g. Be) Compress the material, to make it very dense. Technical Issue 6 What if you want to control the rate of fission (e.g. reactor, not a bomb)? You must absorb just enough neutrons so that the rate of fission is constant. These are the control rods in a reactor. Technical Issue 7 What are the properties of the fission product, e.g. the Ba and Kr in U235 + n = Ba129 + Kr93 + 3n + g These are very radioactive, and their safe disposal presents a serious problem Technical Issue 8 How do you get energy – kinetic energy and g - out of the chain reaction. You let them interact with things and generate heat. Bomb: Heat builds up and everything vaporizes in an explosion. Reactor: remove heat steadily using cooling system. Technical Issue 9 What happens when the neutrons interact with non-fissionable materials. They can be absorbed, causing these materials to transmute into other isotopes, some of which are radioactive. E.g. cobalt, a trace element in steel: Co59 + n = Co60 Co60 = Ni60 + b + g (half life of CO60 is 5.27 years) Environmental Issues Associated with Nuclear Fission Production Storage Use Disposal Production of fissile materials Production of fissile materials Mining Uranium and Concentrating the Ore Concentrating U235 Breeding Pu239 Mining uranium Key Lake mine, Saskatchewan, Canada Mining uranium global distribution of uranium deposits What’s in the Ore ? Ore can be up to 25% uranium oxide. The other 75%, in the form of ground up rock (tailings), needs to be disposed of. Uranium is only mildly radioactive. But the ore contains significant Radon (a gas) and radium (a solid) that are more radioactive. Among uranium miners hired after 1950, whose all-cause Standardized mortality ratios was 1.5, 28 percent would experience premature death from lung diseases or injury in a lifetime of uranium mining. On average, each miner lost 1.5 yr of potential life due to mining-related lung cancer, or almost 3 months of life for each year employed in uranium mining. This wall of uranium tailings, visible behind the trees, is radioactive waste from the Stanrock mill near Elliot Lake, Ontario. In 1975, St. Mary's School in Port Hope, Ontario, Canada was evacuated because of high radon levels in the cafeteria. It was soon learned that large volumes of radioactive wastes from uranium refining operations had been used as construction material in the school and all over town. Hundreds of buildings were found to be contaminated Enriching uranium (separating the U235 from the U238) Process: UF6 gas passed through a cascade of centrifuges Creating Pu: requires reactor French Super Phenix Breeder Reactor then chemical separation of Pu from reactor fuel Sellafield Plant (UK) Legacy problems – lots of leftovers from Manhattan Project and other military weapons projects Problems • Safely shipping of highly-radioactive spent reactor fuel to reprocessing plant • Accidental release of radioactive materials during chemical processing • Disposal of unwanted, but very radioactive by-products Storage • Here we focus mainly – Storage of weapons – Storage of spent nuclear fuel rods Storage 1997 Global Fissile Material Inventories (tonnes) HEU (weapongrade uranium equivalent) ** Military Plutonium 1,700 250 Civil 20 1,100 Total 1,720 1,350 HEU = highly enriched uranium Military stockpiles of Pu by country (tonnes) A 1 GW commercial reactor contains 75 tonnes of low-enriched uranium. About 1/3 of the fuel is replaced every 18 months. Indian Point, about 35 miles north of Manhattan Current Storage at Indian Point 1500 tons spent fuel, stored immersed in “swimming pools” of water, where Shrot-lived radionucleides decay away Storage pool at a Canadian reactor Some fuel moved to casts Commericial Reactor Usage About 20% of US electricity generated By nuclear plants