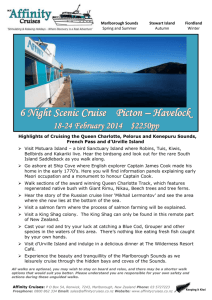

Document

advertisement

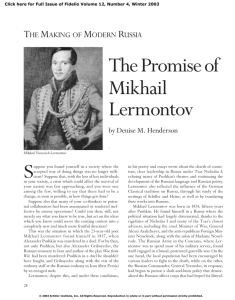

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov is a Russian Romantic writer and poet, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", was the most important Russian poet after Alexander Pushkin's death. His influence on later Russian literature is still felt in modern times, not only through his poetry, but also by his prose. His poetry remains popular in Chechnya, Dagestan, and beyond Russia. Lermontov was born in Moscow to a respectable noble family of the Tula Governorate, and grew up in the village of Tarkhany (in the Penza Governorate), which now preserves his remains. According to one disputed and uncorroborated theory his paternal family was believed to have descended from the Scottish Learmonths[1], one of whom settled in Russia in the early 17th century, during the reign of Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. However this claim had neither been proved nor disproved, and thus remains a legend. After the daughter's death, Yelizaveta Alekseyevna devoted all her love to her grandson, always in fear that his father might move away with him. Either because of this pampering or continuing family tension or both, Lermontov as a child developed a fearful and arrogant temper, which he took out on the servants, and smashing the bushes in his grandmother's garden. As a small boy Lermontov listened to stories about the outlaws of the Volga region, about their great bravery and wild country life. When he was ten, Mikhail fell sick, and Yelizaveta Alekseyevna took him to the Caucasus region for a better climate. There, young Lermontov for the first time fell in love. The intellectual atmosphere in which he grew up differed little from that experienced by Pushkin, though the domination of French had begun to give way to a preference for English, and Lamartine shared his popularity with Byron. In his early childhood Lermontov was educated by a Frenchman named Gendrot. Yelizaveta Alekseyevna felt that this was not sufficient and decided to take Lermontov to Moscow, to prepare for gymnasium. In Moscow, Lermontov was introduced to Goethe and Schiller by a German pedagogue, Levy, and shortly afterwards, in 1828, he entered the gymnasium. Also at the gymnasium he became acquainted with the poetry of Pushkin and Zhukovsky, and one of his friends, Katerina Hvostovaya, later described him as "married to a hefty volume of Byron". This friend had at one time been an object of Lermontov's affection, and to her he dedicated some of his earliest poems, " The Beggar ". At that time, along with his poetic passion, Lermontov also developed an inclination for poisonous wit, and cruel and sardonic humor. His ability to draw caricatures was matched by his ability to pin someone down with a well aimed epigram or nickname. After the academic gymnasium, in the August 1830, Lermontov entered the Moscow University. Having been struck deep by his son's alienation, Yuri Lermontov left the Arseniev house for good, only to die a short time later. His father's death on such a note was a terrible loss for Mikhail, and is reflected in his poems: "Forgive me, Will we Meet Again?" and "The Terrible Fate of Father and Son". The events at the University led Lermontov to seriously reconsider his career choice. He became an officer in the guards. There Lermontov 1830 to 1834 he attended the cadets school in Saint Petersburg, and in due course got a chance to show his incredible strength: he and another junior officer would tie steel ramrods, as if they were simple ropes, into knots, until they were caught at this task . When they were caught doing it,by General Schlippenbach he yelled them "What are you kids doing, pulling pranks like these?" and since then Lermontov would laugh:"Such kids! to tie steel ramrods into knots!" At that time he began writing poetry. He also took a keen interest in Russian history and medieval epics, which would be reflected in the Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov, his long poem Borodino, poems addressed to the city of Moscow, and a series of popular ballads. Borodino The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov To express his own and the nation's anger at the loss of Pushkin (1837) the young soldier wrote a passionate poem the latter part of which was explicitly addressed to the inner circles at the court, though not to the tsar himself. The poem all but accused the powerful "pillars" of Russian high society of complicity in Pushkin's murder. A landscape painted by Lermontov. Tiflis, 1837 The tsar, however, seems to have found more impertinence than inspiration in the address, for Lermontov was forthwith sent off to the Caucasus as an officer in the dragoons. He had been in the Caucasus with his grandmother as a boy of ten, and he found himself at home, with feelings deeper than those of childhood recollection. The stern and rocky virtues of the mountain tribesmen against whom he had to fight, no less than the scenery of the rocks and of the mountains themselves, were close to his heart; the tsar had exiled him to his native land. Lermontov visited Saint Petersburg in 1838 and 1839, and his indignant observations of the aristocratic milieu, wherein fashionable ladies welcomed him as a celebrity, occasioned his play Masquerade. His not reciprocated attachment to Varvara Lopukhina was recorded in the novel Princess Ligovskaya, which he never finished. His duel with a son of the French ambassador led to Lermontov being returned to the army fighting the war in the Caucasus, where he distinguished himself in hand-to-hand combat near the Valerik River. By 1839 he completed his most important novel, A Hero of Our Time, which prophetically describes the duel like the one in which he would eventually lose his life. A Hero of Our Time is actually a tightly knitted collection of short stories revolving around a single character, Pechorin. The short stories comprising this work are intricately connected, and the reader moves from a superficial glimpse of the character's actions to an understanding of his philosophy and of the secret springs of his seemingly mysterious behavior. Lermontov`s poem "Mtsyri" ("The Novice") tells the story of a young man who finds that dangerous freedom is vastly preferable to protected servitude, and speaks as eloquently as anything written by Thomas Jefferson for the spirit of the American revolution. Both patriotic and pantheistic Lermontov's poems had enormous influence on later Russian literature. Boris Pasternak, for instance, dedicated his 1917 poetic collection of signal importance to the memory of Lermontov's Demon, a long poem featuring some of the most mellifluous lines in the language, which Lermontov rewrote several times. M.Vrubel “Demon” The poem, which celebrates the carnal passions of the "eternal spirit of atheism" to a "maid of mountains", was banned from publication for decades. Anton Rubinstein's lush opera on the same subject was also banned by censors who deemed it sacrilegious. On July 25, 1841, at Pyatigorsk, fellow army officer Nikolai Martynov, who felt hurt by one of Lermontov's jokes, challenged Lermontov to a duel. The duel took place two days later at the foot of Mashuk mountain. Lermontov chose the edge of a precipice for the duel, so that if either combatant was wounded, he would fall down the cliff. Lermontov was killed by Martynov's first shot. Several of his verses were posthumously discovered in his notebook. Lermontov's life must be viewed as one of the most epic and dramatic in the history of literature. After attacking the tsar as complicit in the de facto assassination of Pushkin, Lermontov himself fell in a duel that many believe was also the work of a tsarist conspiracy designed to silence nascent rebellion. His major works, which can be readily quoted from memory by many Russians, suffer from the generally poor quality of translation from Russian to English - Lermontov therefore, remains largely unknown to English-speaking readers. •10 questions •Among my classmates(16-17 ears old) Сон В полдневный жар в долине Дагестана С свинцом в груди лежал недвижим я; Глубокая еще дымилась рана, По капле кровь точилася моя. The Dream In noon's heat, in a dale of Dagestan With lead inside my breast, stirless I lay; The deep wound still smoked on; my blood Kept trickling drop by drop away. Лежал один я на песке долины; Уступы скал теснилися кругом, И солнце жгло их желтые вершины И жгло меня - но спал я мертвым сном. On the dale's sand alone I lay. The cliffs Crowded around in ledges steep, And the sun scorched their tawny tops And scorched me -- but I slept death's sleep. И снился мне сияющий огнями Вечерний пир в родимой стороне. Меж юных жен, увенчанных цветами, Шел разговор веселый обо мне. And in a dream I saw an evening feast That in my native land with bright lights shone; Among young women crowned with flowers, A merry talk concerning me went on. Но, в разговор веселый не вступая, Сидела там задумчиво одна, И в грустный сон душа ее младая Бог знает чем была погружена; But in the merry talk not joining, One of them sat there lost in thought, And in a melancholy dream Her young soul was immersed -- God knows by what. И снилась ей долина Дагестана; Знакомый труп лежал в долине той; В его груди, дымясь, чернела рана, И кровь лилась хладеющей струей. And of a dale in Dagestan she dreamt; In that dale lay the corpse of one she knew; Within his breast a smoking wound shewed black, And blood coursed in a stream that colder grew.