Document

advertisement

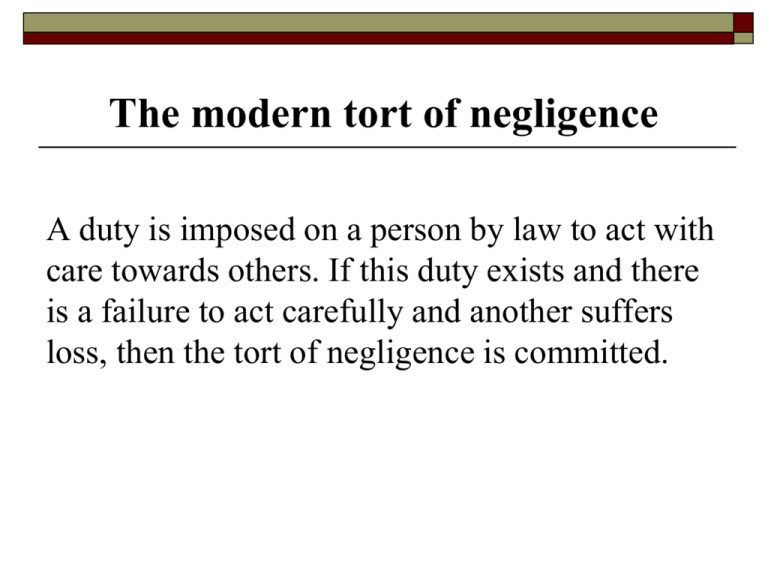

The modern tort of negligence A duty is imposed on a person by law to act with care towards others. If this duty exists and there is a failure to act carefully and another suffers loss, then the tort of negligence is committed. The modern tort of negligence The modern version of negligence was established in 1932 in the decision in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 Negligence has become the most important area of tort law Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 A manufacturer of products which he sells in such a form as to show that he intends them to reach the ultimate consumer in the form in which they left him with no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination, and with the knowledge that the absence of reasonable care in the preparation or putting up of the products will result in an injury to the consumer’s life or property, owes a duty to the consumer to take that reasonable care. Lord Atkin, Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 at 599 The neighbour principle There must be, and is, some general conception of relations giving rise to a duty of care, of which the particular cases found in the books are but instances … That rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes, in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer’s question, ‘who is my neighbour?’ receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, in law, is my neighbour? The answer seems to be – persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question. Lord Atkin, Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 at 580 Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd [2004] HCA 29 Facts: Ms Cole attended a champagne breakfast at the South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club She spent the day drinking at the Club The Club stopped serving Ms Cole after 12.30 pm, but her friends provided her with drinks for the rest of the afternoon At 5.30 pm the Club’s manager asked Ms Cole to leave the premises after she was seen behaving indecently with 2 men Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd The manager offered Ms Cole a taxi home, but Ms Cole rejected the offer in blunt and abusive terms She then left the Club with the 2 men, who assured the manager that they would take care of her At 6.20 pm Ms Cole was struck by a car near the Club and was seriously injured She was found to have a blood alcohol concentration of 0.238% Who was responsible for Ms Cole’s injuries? Why? Negligence and harm Careless acts do not always amount to negligence In negligence, a person is only liable for harm that is the foreseeable consequence of their actions, that is, failure to exercise reasonable care and skill Negligence defined Negligence is the omission to do something that a reasonable person would do or doing something which a prudent and reasonable person would not do Negligence In order to succeed in a negligence action the plaintiff must establish on the balance of probabilities that: the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care the defendant fell below the required standard of care (breach of duty), and the plaintiff suffered damage that was: caused by the defendant’s breach of duty, and not too remote Duty of care The defendant owes the plaintiff a duty of care if it is reasonably foreseeable that any carelessness on the part of the defendant could harm the plaintiff. This is a question of fact. CASE: Grant v Australian Knitting Mills (1933) CASE: Levi v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (1941) A manufacturer does not owe a duty of care to every consumer (e.g. one with abnormal sensitivities) However, there may be special circumstances that give rise to a duty to take special precautions to protect abnormal persons known to be likely to be affected Situations in which a duty of care applies Negligent misstatements – in relation to people being advised Road users – to other road users School authorities – to students Occupier of premises – to persons entering the premises Bailee of goods – to bailor Situations in which a duty of care applies Supplier of goods or services – to persons being supplied Local councils – e.g. to persons requiring zoning information Solicitor holding will – to executor named in will Dog owners – to people who may be bitten Positive action at common law At common law, there will be no breach of duty where the injury arises as a result of a failure to act (i.e. no duty to effect a rescue) Exceptions include: doctor and patient CASE: Rogers v Whitaker (1992) school authority and students local councils statutory authorities Positive action in the legislation Legislation has, in relation to professionals and statutory authorities, introduced a new test for standard of care professionals: Part X, Div 5 – Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) public or other authorities: Part XII – Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) Duty of care At one time, the defendant also owed the plaintiff a duty of care if there was proximity between the defendant and the plaintiff Proximity • • • means nearness or closeness is a limitation on the test of reasonable foreseeability can be: – physical, in the sense of space and time – circumstantial, in the sense of a relationship such as employer-employee or professional adviser-client – causal, in the sense of the closeness or directness between the defendant’s actions and the damage Duty of care Proximity is no longer a common law test for duty of care as today it is determined by the application of the ‘foreseeability’ test and whether there was a vulnerable relationship between D and P The test of proximity was rejected in the case of Sullivan v Moody (2001) Duty of care Three factors are required to be considered for vulnerability: 1. Was the defendant in a controlling position? 1. Was the plaintiff reliant on the defendant? 2. Was the defendant in a position to be protective of the plaintiff? Who was responsible for Ms Cole’s injuries? Issues before the court: Did the Club owe a duty to take reasonable care: to monitor and moderate the amount of alcohol served to Ms Cole? that Ms Cole travelled safely away from the Club’s premises? Does a general duty of care exist to protect persons from harm caused by intoxication following a deliberate and voluntary decision on their part to drink to excess? Did the car driver owe Ms Cole a duty of care? Did Ms Cole in any way contribute to her own injuries? Proximity in psychological damage cases Proximity is still important in psychological damage cases CASE: Jaensch v Coffey (1985) CASE: Tame v New South Wales; Annetts v Australian Stations Pty Ltd (2002) CASE: Gifford v Strang Patrick Stevedoring Pty Ltd [2003] Purely economic loss Financial loss unaccompanied by physical injury to person or property Proximity is also an important test in economic loss cases Courts were initially reluctant to allow recovery Now recoverable in certain situations including: relational interests negligent misrepresentation Negligent misrepresentation Economic loss caused by negligent misrepresentation is recoverable where: a special relationship exists between the parties; the defendant accepted responsibility in the circumstances of the advice; and the plaintiff relied upon the misrepresentation. CASE: Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller and Partners Ltd [1964] Can a disclaimer remove the duty of care? A representor may remove any duty of care by using an appropriate disclaimer. CASE: Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller and Partners Ltd [1964] Negligent misrepresentation ‘Special relationship’ extended: CASE: Mutual Life and Citizens’ Assurance Co Ltd v Evatt (1968) CASE: L Shaddock & Associates Pty Ltd v Parramatta City Council (1981) Duty of care defined narrowly The High Court has made it clear that the key to the existence of a duty of care is whether the information or advice was prepared for the purpose of inducing the representee to act in a particular way. CASE: Esanda Finance Corporation Ltd v Peat Marwick Hungerfords (1997) Relational interests Where the plaintiff is not directly affected but is affected because of their relationship with the primary victim CASE: Perre v Apand (1999) CASE: Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia [2003] CASE: Hill v Van Erp (1997) CASE: Caltex Oil (Australia) Pty Ltd v The Dredge ‘Willemstad’ (1976)