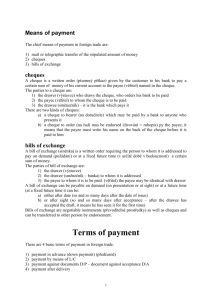

Toronto Dominion Bank v Canadian Acceptance Corp

advertisement