Variations on the Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice

advertisement

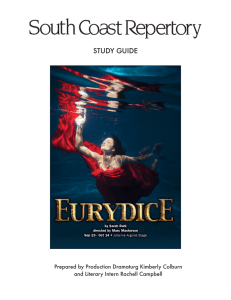

Eurydice

By Sarah Ruhl

Orpheus and Eurydice, Christian Kratzenstein-Stub (1783-1816)

University of Iowa

Spring 2010

Mainstage Production

Research compiled by Christine Scarfuto and Justin Dewey

1

Table of Contents

Bio of Sarah Ruhl

.

.

.

.

Variations on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice

The Greek Underworld

.

3

4

.

.

6

Principle Greek Gods and their Attributes

.

8

Geneology of the Gods

.

.

.

9

.

.

.

.

11

.

.

.

.

13

Production History

.

.

.

.

15

Reviews

.

.

.

.

15

Guide to Helpful Resources

.

.

.

21

Bibliography

.

.

.

22

Hero’s Journey

Archetypes

.

.

.

.

2

About the Playwright: Sarah Ruhl

Sarah Ruhl was born in Wilmette, Illinois. She studied under Paula Vogel at

Brown University and did graduate work at Pembroke College, Oxford. Ruhl

gained widespread recognition for her play The Clean House, a romantic

comedy about a physician who cannot convince her depressed Brazilian maid

to clean her house. It won the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize in 2004. It was a

Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2005. Her play Eurydice was produced off-Broadway

at New York's Second Stage Theatre in June-July 2007. Prior to that it had

been staged at Yale Rep (2006), Berkeley Rep (2004), Georgetown University,

and Circle X Theatre. Ruhl is also known for her Passion Play cycle that

opened at Washington's Arena Stage in 2005, and subsequently was produced

by the Goodman Theatre and Yale Rep. The Passion Play is scheduled to make its New York City

premiere in spring 2010 in a production by the Epic Theatre Ensemble in Brooklyn, New York. Her play

Dead Man's Cell Phone premiered in New York City at Playwrights Horizons in 2008 in a production

starring Mary-Louise Parker. It had its world premiere at Washington D.C.'s Woolly Mammoth Theatre

Company in 2007. It was produced at Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2009. Other plays include Orlando,

Late: A Cowboy Song and Demeter in the City. In September 2006, she received a MacArthur Fellowship.

The announcement of that award stated: "Sarah Ruhl, 32, playwright, New York City. Playwright creating

vivid and adventurous theatrical works that poignantly juxtapose the mundane aspects of daily life with

mythic themes of love and war." In February 2009, her play In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play)

premiered at Berkeley Rep. The play is scheduled to open on Broadway at the Lyceum Theatre with

previews starting on October 22, 2009 and an official opening in November 2009. This marks Ruhl's

Broadway debut. John Lahr gives a brief review of Ruhl’s work in The New Yorker: “But if Ruhl’s

demeanor is unassuming, her plays are bold. Her nonlinear form of realism—full of astonishments,

surprises, and mysteries—is low on exposition and psychology. “I try to interpret how people subjectively

experience life,” she has said. “Everyone has a great, horrible opera inside him. I feel that my plays, in a

way, are very old-fashioned. They’re pre-Freudian in the sense that the Greeks and Shakespeare worked

with similar assumptions. Catharsis isn’t a wound being excavated from childhood.”

Plays by Sarah Ruhl:

The Melancholy Play (2001)

Lady with the Lap Dog, and Anna around the Neck (2001)

Virtual Meditations #1 (2002)

Orlando (2003)

Eurydice (2003)

Late: A Cowboy Song (2003)

Passion Play (2003-2004, Helen Hayes Awards nomination for Best New Play)

The Clean House (2004, Susan Smith Blackburn Prize, Pulitzer Prize Finalist)

Demeter in the City (2006)

Dead Man’s Cell Phone (2007)

In the Next Room (or the Vibrator Play) (2009)

3

Variations on the Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice

As classicist M. Owen Lee said in his book entitled Virgil as Orpheus, “A great artist never

touches a myth without developing, expanding, and sometimes radically changing it.” There have been

many different interpretations of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice; the first versions harkening back to

Ancient Greek myths and frescoes, which parlayed themselves into poems, songs, operas, and paintings

for centuries. Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice is unique among these, in that instead of focusing on the story of

Orpheus, the great demigod and musician with legendary powers of reincarnation, it focuses on the story

of Eurydice, whose action in the play (calling out to Orpheus as they ascend into the world) is what

causes her return back to the underworld. She is given both more agency and a more poignant dilemma

than in most other variations on the myth, the most drastic of which is the relationship she cultivates with

her dead father. But to further understand these differences, we should first take a look at the origin of the

myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, found in its first complete version in Virgil’s Georgics, and a generation

later in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

To understand the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, we first must fully comprehend the story of

Persephone. Persephone, goddess of the Underworld, was the beautiful daughter of Demeter and Zeus.

One day when she was a young maiden, she was out picking flowers with some Nymphs when Hades

rose up from a cleft in the earth and stole her away to be his bride. Demeter searched everywhere for her

lost daughter, and eventually Helios, the Sun, told her what happened. Zeus forced Hades to return

Persephone to the upper world; however, Hades tricked Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds (and

those who eat and drink in the underworld must stay there for eternity). Therefore, Persephone was able

to be reunited with her mother, but had to return to the underworld for one season each year. This myth

originally explained the seasons. It is vital to understand this story because Persephone’s sympathy for

Orpheus for having lost a loved one is part of what allows her to give him permission to regain his bride.

Virgil’s Georgics

In this version of the myth, Eurydice was fleeing from the shepherd Aristaeus, a demigod in his

adolescence, not yet fully matured who tended to cause trouble. She fled, headlong along a river, and

didn’t see the poisonous snake that lurked in the high grass. It bit her, and she died. Orpheus, son of

Apollo (sometimes of the Thracian river god Oeagrus) and the muse Calliope, was famous for his

beautiful music and was married to Eurydice. When she died, his song made the whole world weap: the

stones, the trees, and the waters. He went through the gates of hell to find Hades to get his love back. He

played his sad music and Cerebrus (the three headed dog) was silenced, the snakes in the Furies’ hair

were transfixed, and Ixion’s wheel stopped turning. Persephone, goddess of the underworld, commanded

that he go back the way he came and that Eurydice was to follow behind, unseen.

Just as they were coming on the brink of the upper world (light was in sight), Orpheus was seized by what

Virgil describes as “the madness of love,” and turned to look back at Eurydice. Virgil claims that those in

hell would forgive him if they only knew the madness of love. Eurydice cried “What is it, what madness,

Orpheus, was it that has destroyed us, you and me, oh look!” Sleep begins to cover her swimming eyes,

and she reaches her hands out, towards him, forevermore as she falls back into the depths of hell.

For seven months afterwards, he lay beside the river Strymon and wept, and charming the trees with his

sad songs. One day, the Ciconian Bacchantes in a nocturnal orgy tore his body to pieces and scattered

them everywhere. He is never to see his love again. However, his lute plays the saddest songs as it floats

down the river, and though he is beheaded, he still sings his sad songs.

4

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Orpheus is a musician and poet of Thrace, the son of Apollo and Calliope, who is in love with and

marrying Eurydice. Their wedding doesn’t go as planned: Hymen didn’t bring the usual joyous fervor he

brought to weddings, and the torch he held sputtered throughout the ceremony. Later that day, she was

roaming in a field with nymphs when she got bit by a poisonous snake and died. Orpheus played a sad

song that made the whole world weap. He went to Hades to ask for his wife back, and played him his sad

song. The song stopped the waters of hell, Ixion’s wheel, the eating of the vultures, and the Furies even

wept. Sisyphus sat rapt on his rock. At the urging of Persephone, Hades allowed for Eurydice to return to

the upper world on the condition that Orpheus not look back at her throughout their trek out of the

Underworld. The two made it almost all the way to the upper world—the light was in sight—when

Orpheus, fearing Eurydice would faint, looked back. Eurydice fell back into the depths of the

Underworld, making no complaint—for she was loved.

Orpheus was not allowed to cross the river Styx a second time, and he fasted on the banks of the river in

anguish for seven days. For three years after, he held himself aloof from women, though they burned in

passion for him. He eventually took to living in the forests near the river, castrated himself, and sang his

sad songs to the trees, which were charmed by him. One day, a group of Thracian women found him

singing on the banks of the river and beat him to death for scorning their love. Orpheus travelled back to

the Underworld and found Eurydice in the Elysian fields, where they stroll together and he can look back

at her with no danger. Bacchus punished the women by turning them into gnarly trees.

Significant Differences in these Interpretations

Of the most significant differences in these interpretations is that Ovid’s version seems on the whole

kinder than Virgil’s. The mischievous shepherd, Aristaeus (perhaps seen in Ruhl’s version as the Nasty

Interesting Man) doesn’t exist, it is entirely the fault of Orpheus’s temporary madness that he is torn from

his love forever (instead of, in Ovid’s, how he is simply concerned his wife may faint). And importantly,

in Ovid’s telling of the tale, the lovers are eventually reunited in the Underworld, while in Virgil’s they

are not. Below are some further interpretations of the myth from around this time period.

Other Interpretations of the Myth

EURIPIDES: In his earliest surviving play, Euripides tells the story of Admetus, King of Thassaly, who

allowed his wife to die in his place. He claims that if he only had the song of Orpheus, he would be able

to move the powers of hell to get his wife back.

PLATO: In this version, Orpheus was only given a phantom version of his wife. According to Plato,

because he was a musician he didn’t want to die for his love, so he died at the hands of women. It should

be pointed out that Plato was against music making.

ISOCRATES: In Busiris, Isocrates (an ancient Greek Rhetorician and orator) wrote that Orpheus

successfully got out of the Underworld with Eurydice, and implied he was the leader of a cult that

promised reincarnation. Other versions of the myth also imply that Orpheus held secrets about the

afterlife, and was descending into the Underworld to find them.

5

The Greek Underworld

There are several interpretations and descriptions of the Greek Underworld. The most important thing to

remember is that with the Greek Underworld, like most Greek Myths, to the Underworld also differs

according to context. Below are examples of the Underworld as told by specific people, as well as some

excerpts of different aspects of the Greek Underworld that seem to be common among authors.

Homer’s Underworld: A brief Overview

Traveling to the Underworld :

Step 1: Sail to the edge of the world, arriving on the beach of the ocean that encompasses

existence.

Step 2: Arrive at the spot where the two rivers of the Underworld, Pyriphlegethon (Fire) and

Kokytos (Lamentation) converge into the River Acheron (Groaning).

Step 3: Sacrifice a ram and a ewe. Collect the blood in a vessel to attract the souls of the dead,

who upon drinking the blood will gain the ability to speak with living humans.

Homer describes the Underworld in the story of Odysseus. When in the Underworld, Odysseus sees many

examples of punishment, most of which are now told as common stories in mythology. Some examples

include: Tityos having his liver pecked out by vultures, a punishment for raping the goddess Leto, or

Sisyphos who pushes a boulder up a hill for eternity for trying to escape death. One thing that is important

about these punishments, is that the crimes are explicitly crimes against the honor of the gods.

Aristophanes’ Underworld: A brief Overview

Aristophanes provides a look into the Underworld in his satirical farce, Frogs. This view of the

Underworld starts to provide a look into the geographical landscape of the Underworld. There is an

account of Dionysus having to take Charon’s Ferry across a bottomless lake. Charon, being the fisherman

of the dead. Another important aspect of Aristophanes’ Underworld is the idea that there are different

groups of people in different areas of the Underworld. Also, the dead do not lose their identity in the

Underworld, according to this account. In fact, the philosophers in the Underworld are fully capable of

debating as if they never died.

Rivers of the Underworld

In Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice, there are many references to ‘the river’. In Greek Myth, there are three

common rivers found in the Underworld, however, the River Styx is the river most people associate with

the underworld. Plato said that the River Styx flowed into a massive lake. It is a common thought that

Charon, the fisherman of the dead, rowed the dead souls over the River Styx to the underworld. Another

river, the River Acheron, is also common, and is said by Euripides to be the place where Charon rowed

the dead soul of Alkestis. This River, while common, is thought of by less to be Charon’s River of choice.

In both cases, the River is something very sacred that shifts within the context of the myth. Both rivers,

according to myth, both had locations in the real world. Styx was located in Northern Arcadia, and

Acheron was located in the Thesprotian Mountains of Northern Greece. Ideas differ among myths and

authors on whether or not one loses their memory and identity when entering the underworld. For

example, in The Odyssey, the dead fully retain their identities and memories, in Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice,

the dead are supposed to forget their memories when dipped in “the river”. This river is referring to the

River Lethe. This was the river that would cause souls to forget their existence if dipped in or drank

6

from. In the overall geography of the underworld, this river was located near the Asphodel Meadows, or

the place where the ordinary souls spent eternity.

Erebus

The Greek Underworld was separated into two major parts. The first part was called Erebus, this is where

dead souls first went after death. Charon would ferry the souls across the River Styx to the Gates of

Erebus. Then the Souls would proceed to Tartarus. This is also the place where the unburied souls spent

eternity, they weren’t allowed to proceed into Tatarus, as the gate was guarded by Cerberus, a threeheaded dog.

Tartarus

This is the place in the underworld where the rest of the dead would spend eternity, based upon their

judgment. According to myth, there were three judges of the dead, who would sentence the soul upon

arrival. Tartarus was divided into three parts, The Fields of Punishment, Asphodel Meadows, and the

Elysium.

Fields of Punishment

After judgment, those souls who had committed crimes against the Gods would be sent here.

This is the place in Tartarus where people like Sisyphus, Tantulus, and Tityos would be

found.

Asphodel Meadows

The place where ordinary or indifferent souls went to spend eternity after judgment. These

souls did not commit any crimes that would send them to the Fields of Punishment, and they

also did not achieve greatness or any other recognition that would set them apart and earn

themselves a place in the Elysium.

Odysseus on the Asphodel Meadows

There are Meadows that I can’t describe,

the landscape as level as see in

dreams, or visions where nothing is thought of

but the moment. It is not clear, and

memory exhausts itself, omitting

something. Silence is a part of it,

and distance reaching in a small space.

Since there are few instances in the

world of such a thing, it fills our sleep

with a pattern for Elysium.

Our friend Achilles walked in these same

fields. There in the whiteness of flowers

where we could not go he thought of us,

pained by death beyond our speaking.

Elysium (Or Elysian Fields)

This is part of Tartarus where the virtuous or heroic souls went to rest. It is said that the Ruler of the

Elysium is Kronos, Zeus’ Father. Inside the Elysium there is said to be a lake, and in the middle of the

lake there was the Isle of the Blest. The Isle of the Blest is where distinguished souls went to spend

eternity. Achilles is an example of the type of soul that was destined for the Isle of the Blest.

7

Principle Greek Gods and Their Main Attributes

GOD

Zeus

Hera

Poseidon

Hades

Aphrodite

Demeter

Artemis

Apollo

Athene

Ares

Hephaistos

Persephone

Hestia

Hermes

Dionysus

Pan

Eros

Activity/Attributes

Sky, Weather, Father of Gods

and Mortals

Wife of Zeus, Integrity of

Marriage

Sea, Earthquake, Raw energy of

Bull and Horse

Lord of the Underworld

Sex, Love

Corn, Fertility of the Land,

Hunting, wild animals, Aid of

Women in Childbirth

Music, divination of prophecy,

purification, healing (later- Sun)

Craftsmanship, warfare

The fury of War

Physical lameness, metalwork

and artisan

Bride of Hades, Queen of

Underworld, daughter of

Demeter

(fire of) Hearth

Divine intermediary, messenger,

guide of souls to Hades, bringer

of fertility to flocks

Ecstasy, madness of intoxication,

wine, exuberance (later- theatre)

God of lonely, rustic wilderness,

induces ‘panic’

Sexual desire

8

9

10

The Hero’s Journey

Being that we are dealing with a re-creation of a myth, it is important that we examine Joseph

Campbell’s idea of the Hero’s Journey. Campbell (1904-1987) was a mythologist, best known for his

work in comparative mythology and religion. His work The Hero with a Thousand Faces is arguably his

best known work for introducing the idea of the Hero’s Journey into popular thinking. The hero’s

journey is a helpful tool for observing and analyzing the progression of myths and stories from the

beginning of time, all around the world. Campbell observed that many of the myths and religious stories

from around the world followed the same basic structural pattern, and utilized similar archetypal

characters. Below is an extremely simplified version of the hero’s journey:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder:

fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from

this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

The different possible steps of the hero’s journey are outlined on the following page. However, it is

important to remember that a hero may not follow each of these steps: each story is different, and this

outline can be molded and edited based on the story. It is also important to realize that the hero’s journey

can be constructed from different character’s points of view. For example, in Ruhl’s Eurydice, you could

argue that Orpheus is never able to “return with the Elixir,” because he is unable to bring Eurydice out of

the Underworld and back to the “known” world. If we were to look at this from Eurydice’s point of view,

however, we could argue that she refuses to return to the ordinary world, and therefore gets stuck in the

“unknown” world (the Underworld). It’s important to remember, however, that the myth can be analyzed

in a number of different ways in relation to the hero’s journey—ultimately, it is a helpful tool for looking

at the journeys taken by the characters in this play. Below is one example of an illustration of the hero’s

journey; on the following page is another.

11

12

Archetypes

Joseph Campbell was heavily influenced by psychologist Carl Jung’s idea of archetypes. An archetype is

an original ideal of a person, or an ideal model of something. It is a prototype from which other things are

copied, emulated, or compared. According to Jung, the human race has a collective unconscious, and in

that unconscious are certain archetypal personalities which we can all recognize and identify. Symbols are

also part of this collective unconscious that Jung has introduced: just as there are archetypal characters,

there are archetypal symbols that appear in myths and religious stories, in addition to our dreams and in

our subconscious. Our loathing of snakes, symbolizing evil and temptation, is one of these symbols. The

following page is a sheet containing many of the typical archetypes found both in Ruhl’s Eurydice and

other myths. Below are some visual examples of these archetypes. Again, it is important to recognize that

one character can fulfill more than one archetype at one…for example, The Nasty Interesting Man could

be seen as both a shape shifter and a herald. Ultimately, looking at archetypes is just another helpful way

of analyzing this play and its characters.

An example of a Shape shifter

An example of the Wise Old Wizard

13

14

Production History

Madison Repertory Theatre, September 2003

Berkeley Repertory Theatre, October 15- November 21, 2004

Yale Repertory Theatre, September 22, 2006

Second Stage Theatre, June 18th, 2007 September 16, 2008 - October 26,

Artist Repertory Theatre, September 16, 2008 - October 26, 2008

Alliance Theatre, March 2008 to April 2008

ACT (Seattle), September 2008, to October 2008

Yale University, November 2009

Ithaca College, December 2009

Production Information and Reviews

Madison Repertory Theatre, September 2003

Director: Richard Corley

Set Design: Narelle Sissons

Lighting Design: Rand Ryan

Costume Design: Murell Horton

Sound Design: Darron L. West

Cast

Eurydice –

Her Father OrpheusA Nasty Interesting ManGrandmotherBig StoneLittle StoneLoud StoneKarlie Nurse

Laura Heisler

John Lenertz

David Andrew McMahon

Scot Morton

Diane Dorsey

Jody Reiss

Polly Noonan

Berkeley Repertory Theatre, October 15- November 21, 2004

Director: Les Waters

Review:

San Francisco Chronicle

Robert Hurwitt, Chronicle Theater Critic

Friday, October 22, 2004

Awash in a young writer's bracing, lucid 'Eurydice'

"Love is strong as death," sings the sage sensuality of "The Song of Solomon." No, answers the

earthly wisdom of ancient Greek mythology in the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, once death claims a

mortal, even the inspired musician cannot retrieve his beloved bride from the Underworld. Ah, says Sarah

Ruhl in the shimmering "Eurydice" at Berkeley Repertory Theatre, it's a little more complicated than that.

Touching, inventive, invigoratingly compact and luminously liquid in its rhythms and design,

"Eurydice" reframes the ancient myth of ill-fated love to focus not on the bereaved musician but on his

15

dead bride -- and on her struggle with love beyond the grave as both wife and daughter. Yes, daughter. In

Ruhl's wondrously rich, timelessly contemporary reimagining, Eurydice's relationship with her dead

father is as vital as and in some respects more touching than her love for the heartbroken husband who

almost succeeds in rescuing her from death.

It's a local debut that provides good evidence why Ruhl has rapidly gained a reputation as a

young writer to watch. "Eurydice" premiered last year at Wisconsin's Madison Repertory Theatre and is

receiving its West Coast premiere in the production that opened Wednesday in Berkeley. It's movingly

and gracefully brought to life by a terrific cast in Associate Artistic Director Les Water's lucid and

visually astonishing underground bathhouse staging on the Rep's versatile Thrust Stage.

Water oozes down the vast green-tiled walls and across the similarly covered floor of Scott Bradley's

richly evocative set. Its drips fill the spaces between wonderfully eclectic rock and classical snippets in

Bray Poor's compelling soundscape. It gushes from the vibrant blue antique pump that stands in for Lethe,

the mythic river of forgetfulness in Hades, and it pours down in a heavy rain inside the ingenious elevator

that serves as the River Styx.

Water plays a large part in death in "Eurydice," and in life as well. Maria Dizzia's glowing,

enthusiastic Eurydice and Daniel Talbott's vibrant Orpheus -- energetically abstracted as his mind keeps

wandering to his music -- bask on a beach in the opening scene. They're young, full of life and head over

heels in love, even if -- in Ruhl's playfully canny, poetic dialogue -- they can't help noticing certain

defects in each other. Orpheus isn't nearly as interested in words or ideas as she is. Eurydice can't really

carry a tune.

Even as the young lovers prepare for their wedding, images of the Underworld begin to make

themselves felt. A gentle, almost achingly genteel and thoughtful Charles Shaw Robinson -- fresh from

playing another ancient ghost in "The Persians" next door at the Aurora Theatre -- appears and delivers

lovely thoughts on being the father of the bride at a wedding he can't attend; he's dead. He's an atypical

denizen of Hades, though, having kept his memory and a yearning desire to communicate with his

daughter.

Tiles on the wall become letters from the Underworld. A remarkable, mock- Beckett-ian funny

Chorus of Stones -- the wonderfully mournful Ramiz Monsef, creepy T. Edward Webster and stentorian

Aimée Guillot, zombie-pale in Meg Neville's ghostly Edwardian costumes -- sings the rules and pleasures

of after-death oblivion. An eerily insistent, dangerously nerdy Mark Zeisler introduces a whiff of

brimstone as the Nasty Interesting Man who starts stalking Eurydice.

The tale unfolds with classical precision in a delightfully creative postmodern mix. Eurydice dies at the

wedding. The heartbroken Orpheus searches for her, singing so mournfully -- as the legend has it -- that

the very stones weep (and the Stones do). He wins the Lord of the Underworld's (Zeisler) grudging

concession to let him retrieve Eurydice on the condition that he never look back to see if she's following

him on the long trek back to life. Which, of course, he does.

Ruhl follows the essential outline of the tale as faithfully as most tellers have from Ovid to

Monteverdi to Cocteau to Marcel Camus' "Black Orpheus." But she tells it from Eurydice's point of view

and blends in elements of everything from "Alice in Wonderland" and the Big Bad Wolf to the myth of

Persephone, "Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree," "King Lear" and the Gershwins' "I Got Rhythm." She

depicts the seductiveness of oblivion and mocks evil, turning the Lord of the Underworld into a

dangerously spoiled brat.

Waters' sumptuously staged and musically paced production mirrors the script's playfulness at

every turn. Bradley's stunning and versatile set is full of surprises reminiscent of the ingenious

productions of Mary Zimmerman, for whom he's designed several shows. The whole piece is packed with

delightful grace notes, small and large, from the slash of a fluorescent blue tube and the flickering of the

elevator's descent in Russell Champa's lighting design to the headphone logo on the music-obsessed

Orpheus' shirt, the ephemeral house of string Eurydice's father builds for her or the intimations of torment

in the ferocious fangs of a stuffed baboon.

Waters and his cast create a pregnant tension between comedy and pathos that serves the text

well. They vividly contrast the passion of the distressed Orpheus with the timeless serenity of the

16

Underworld. No matter how well we know what's bound to happen, Orpheus and Eurydice's attempt to

return above ground attains its dramatic suspense amid a cacophony of sound and lowering lights.

More than anything else, Ruhl's "Eurydice" derives emotional depth from its multilayered depiction of a

woman torn between her lover and her father. Robinson and Dizzia vividly bring the father-daughter bond

to life just in the deeply touching way in which he walks her down the aisle -- once, by himself, in

imagining her wedding, and again when he leads her to Orpheus in the Underworld. Their scenes in

Hades, as he patiently restores the memories she's lost, are rich in beautifully observed tenderness.

In some respects, Dizzia's and Talbott's passion isn't as fully realized, but that's partly because of their and

Ruhl's success in depicting the complexities of love. Ruhl's Orpheus and Eurydice have their moments of

doubt and recriminations, which leaven their romance with some reality. Once separated, though, their

pangs of longing strike heartbreaking chords. And Orpheus' proposal is so delightfully depicted that their

love is well established early on.

Not that their love proves as strong as death in the end. "Many waters cannot quench love,"

Solomon continues, "neither can the floods drown it." He wasn't considering the waters of Lethe, though.

Ruhl is, and she uses its waters of oblivion to bring "Eurydice" to a conclusion that's as poignantly

rewarding as it is luminously ambiguous.

Yale Repertory Theatre, September 22, 2006

Director: Les Waters

Set Design: Scott Bradley

Lighting Design: Russel H. Champa

Costume Design: Meg Neville

Sound Design: Bray Poor

Cast

Eurydice –

Eurydice’s Father OrpheusA Nasty Interesting Man/Lord of the UnderworldBig StoneLittle StoneLoud Stone-

Maria Dizzia

Charles Shaw Robinson

Joseph Parks

Mark Zeisler

Ramiz Monsef

Carla Harting

Gian-Murray Gianino

Review:

New York Times

Anita Gates

October 8, 2006

CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK; Love and Loss, in This Life and the Next

I cry at the theater, sometimes even when the play isn't very good. But normally I know when it's

coming; it starts with a little mistiness, allowing me time to dig out the Kleenex. But on Tuesday night, as

I watched the final minutes of the Yale Rep's knockout production of Sarah Ruhl's ''Eurydice,'' the tears

came with the suddenness of grief. Ms. Ruhl is dealing with the big subjects here.

''Eurydice'' is the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice told from the woman's point of view. Orpheus, a

brilliant lyre player, is heartbroken when his new bride, Eurydice, is bitten by a snake and dies. He

appeals to the Furies with his seductive music, and the Lord of the Underworld agrees to return Eurydice

to life. On one condition: Orpheus must come to Hades and lead her out without ever looking back at her.

But a man in love can't resist stealing a glance, and he loses her again, this time forever.

17

In Ms. Ruhl's version, things happen in much the same way -- instead of being bitten by a snake,

this heroine takes a fatal fall from a high-rise apartment -- but rather than focusing on Orpheus' grief, the

play spends most of its time in Hades, where Eurydice is adjusting to the afterlife.

Writing in The New York Times last week, Charles Isherwood pronounced the production ''devastatingly

lovely -- and just plain devastating,'' and possibly ''the most moving exploration of the theme of loss that

the American theater has produced since the events of Sept. 11, 2001.''

As Mr. Isherwood points out, Ms. Ruhl began work on the play before the terrorist attacks. That isn't

surprising, because while ''Eurydice'' is certainly a play for our fearful times, it is about every death, every

loss, every paralyzing pang of grief.

When Eurydice (Maria Dizzia) meets her father (Charles Shaw Robinson) in the underworld,

their reunion is agonizingly sweet. He recognizes her only because he has not dipped into the river of

forgetting as he was supposed to (apparently the after-death version of hiding your medication under your

tongue). The realization that you can always change your mind, kill the pain by choosing to forget and

curl up into a semiconscious fetal ball is a horrible lesson on this side and the other.

The playwright who has looked into the heart of darkness and found an awful beauty is a young human

being, if clearly an old soul. Ms. Ruhl, 32, grew up in suburban Chicago, studied with Paula Vogel at

Brown University and now lives in Southern California. She was one of this year's winners of the

MacArthur Foundation's ''genius'' grants.

Her work has been bouncing around the country's finest regional theaters for a few years, and she

is finally having her New York moment. ''The Clean House,'' a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2003, began

previews at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater at Lincoln Center on Thursday and is scheduled to open on

Oct. 30. In it, Ms. Ruhl finds unexpected meaning in the story of a doctor (Blair Brown) whose Brazilian

maid (Vanessa Aspillaga) would rather be a stand-up comic.

It should be mentioned that Ms. Ruhl's work is very funny, sometimes in a low-key way (''All the

interesting people I know are dead or speak French,'' the living Eurydice says at her wedding reception)

and sometimes verging on vaudeville (the Lord of the Underworld rides a tricycle).

Neither laughter nor the flawless production is what most audiences will praise about ''Eurydice.'' The

heroine's arrival in Hades (by elevator, accompanied by a stunning surge of rain) is memorable for

technical reasons, but it wouldn't mean a thing without this playwright's singular voice.

18

Photos from http://www.yalerep.org

Second Stage Theatre, June 18th, 2007

Director: Les Waters

Set Design: Scott Bradley

Lighting Design: Russel H. Champa

Costume Design: Meg Neville

Sound Design: Bray Poor

Cast

Eurydice –

Eurydice’s Father OrpheusA Nasty Interesting Man/Lord of the UnderworldBig StoneLittle StoneLoud Stone-

Maria Dizzia

Charles Shaw Robinson

Joseph Parks

Mark Zeisler

Ramiz Monsef

Carla Harting

Gian-Murray Gianino

Review:

New York Times

Charles Isherwood

June 19, 2007

The Power of Memory to Triumph Over Death

The most famous unheeded advice in the history of Western literature may be the admonition

given by the ruler of the underworld to Orpheus, when that grieving youth went down to retrieve his wife,

Eurydice, from the depths, and the lovers began their journey back upward.

It was something along these lines: “Hey, fella, remember: Don’t look back.”

Spoiler alert! He did.

From this woeful act of disobedience a whole universe of art has been spun over the last couple of

millenniums, poems and operas and ballets in the double digits by now, even a classic movie or two. No

doubt somewhere on YouTube, a Greek-myth-loving geek with a Webcam has done a two-minute goof

on the tale.

In her weird and wonderful new play, “Eurydice,” the gifted young writer Sarah Ruhl has adapted

this mournful legend with a fresh eye, concentrating not on the passionate pilgrimage of Orpheus to

retrieve his bride but on Eurydice’s descent into the jaws of death. What she finds there, and what she

learns about love, loss and the pleasures and pains of memory, is the subject of Ms. Ruhl’s tender-hearted

comedy, which opened last night at the Second Stage Theater in a rhapsodically beautiful production

directed by Les Waters.

I suspect that “Eurydice” will get under your skin either in all the right ways or all the wrong

ones. I first saw the play, in this production, at Yale Repertory Theater last fall, and its hallucinatory

imagery and emotional allure have remained with me. Encountering it again, I staggered out of the theater

in the same state of sad-happy disorientation that I recall from my initial viewing.

Ms. Ruhl’s theatrical vision is an idiosyncratic one. She is not a journalist of domestic life, as so

many playwrights today seem to be, but an adventurer who is not afraid to blend the quotidian and the

fantastic, deep feeling and airy whimsy. The plot of Ms. Ruhl’s surreal comedy “The Clean House,” seen

at Lincoln Center Theater earlier this year, sometimes turned on jokes told in Portuguese that were left

untranslated. Likewise, much in “Eurydice” could mystify theatergoers used to reclining on the

comforting cushions of linear narrative and naturalistic dialogue.

The fabled creatures of “Eurydice” may look like people you’ve seen on the subway, but they

speak in images plucked from the blue sky of their mythic imaginations. You might almost wish there

were subtitles here, alerting you to the inner meaning of the lyrical, illogical and, yes, sometimes overly

19

quirky dialogue. (The most sensibly spoken characters onstage are probably the blunt-spoken chorus of

stones, strange creatures with pea-green faces, in Victorian garb, who keep telling Eurydice to shut up and

get used to being dead.)

But to be moved by “Eurydice,” you just need to tune in to the play’s insistent heartbeat, the

rhythmic threnody woven by its language, its subterranean feeling and its strangely potent imagery. Ms.

Ruhl sees her plays as much as she hears them — a rare gift among playwrights — and some of the most

striking moments in the play are wordless ones.

Take, for instance, the tender, wrenchingly sad vision of Eurydice’s dead father, who can watch

his daughter’s progress from the underworld below, miming the act of walking her down the aisle on her

wedding day. He nods proudly at the guests on either side, gives her an encouraging smile, offers her up

with a mixture of resignation and worry and joy. And he is utterly alone. As performed with impeccable

simplicity and grace by Charles Shaw Robinson, this small vignette is among the most desolate and

moving moments I can remember seeing on a stage.

Eurydice, played with radiant open-heartedness by Maria Dizzia, falls to her death just after

marrying Orpheus. She descends in an elevator to the underworld, but her reunion with her father is

bittersweet. The dead are dipped in the waters of forgetfulness, and Eurydice has lost all that she once

knew, her husband’s name, much of her own history, language itself. She takes Dad for a hotel porter.

The helpful stones, played with pop-eyed intensity by Gian-Murray Gianino, Carla Harting and

Ramiz Monsef, insistently bray at Eurydice that death is much easier if you take refuge in the easy solace

of forgetting. (Life is that way, too, of course.)

But “Eurydice” movingly suggests that commemorating life, its pleasures and problems, its

transience and pain, is the only way to triumph over death and loss. Eurydice’s father helps restore her

memory, anecdote by anecdote, and her vocabulary, word by word, rebuilding the universe of the world

they have lost in the prison of death.

At one point he reads to her from “King Lear”: “We two alone will sing like birds in the cage.”

“Eurydice” is on one level an ode to the sustaining power of the love between father and daughter. (Ms.

Ruhl wrote it after the death of her father.) It considers, too, how hard it is for two human beings to

achieve the harmony of perfect romantic love.

Orpheus, played with a fine, fierce ardor by Joseph Parks, is, of course, a composer; Eurydice

hears music mostly in words. When he descends to fetch her back, Eurydice faces a painful choice: to reenter the world above, where imperfect human love and the potential for pain awaits, or remain below

where she is beyond its reach? Either choice involves risk and loss.

Mr. Waters and his design collaborators have framed Ms. Ruhl’s play with uncommon sensitivity

and stylistic sympathy. (In a less felicitous production, I can imagine the play cloying into preciousness.)

Scott Bradley’s tilted vision of the underworld as a slightly dilapidated spa, wallpapered in letters written

from the dead to the living, perfectly matches the writing’s off-kilter tone. The shimmery, dank lighting

by Russell H. Champa echoes the quicksilver changes in tenor.

And the selection of music likewise parallels the emotional currents without overwhelming the

breezy playfulness of the dialogue. (Arvo Pärt’s haunting “Spiegel im Spiegel,” for piano and violin, is

used to particularly fine effect.)

“What happiness it would be to cry,” Eurydice says when she enters the underworld and

discovers that she’s lost her grasp on emotional response, along with her memory. Perhaps more than

anything else, the eerie wonderland of “Eurydice” evokes the discombobulating experience of grief and

loss, the desperate need to move on and the overwhelming desire never to let go — to turn and look back

just one more time.

20

Guide to Helpful Resources

Below is a list of helpful resources and their descriptions that the dramaturgs will have in rehearsal at all

times:

Virgil’s Georgics: The complete original myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Second generation interpretation of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Virgil as Orpheus by M. Owen Lee: A companion book to Virgil’s Georgics, going in depth about

further history of the myth and meanings within Virgil’s poem.

Greek Myths by Robert Graves: Gives a basic, easy to understand background information about Greek

mythology.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell: Further in depth information on the hero’s

journey and descriptions of archetypes.

21

Bibliography

Buxton, R. G. A. 2004. The complete world of greek mythology. London : Thames & Hudson.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books, New York: 1949.

Ferry, David. The Georgics of Virgil. Farber, Straus, and Giroux, New York: 2003.

Graves, Robert,. 1988. The greek myths / robert graves. Vol. Complete and unabridged ed. in one

volume, 1st ed. Mt. Kisco, N.Y. : Moyer Bell.

Koehler, Stanley. 1982. Odysseus speaks of asphodel. The Massachusetts Review 23, (2) (Summer): 277.

Melville, A.D. (trans). Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1986.

Pfister, Friedrich,. 1961. Greek gods and heroes.. Götter- und heldensagen der griechen. english.

London,: Macgibbon & Kee.

Review Websites

https://www.acttheatre.org/TicketsPlays/Play.aspx?prod=1052

http://www.playbill.com/news/article/108876-Sarah-Ruhls-eurydice-Opens-Off-Broadway-June-18

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2004/10/22/DDGRH9D2111.DTL

http://theater.nytimes.com/2007/06/19/theater/reviews/19seco.html

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9504E5D91530F93BA35753C1A9609C8B63

http://www.artistsrep.org/press/reviews/eurydice-oregonian.aspx

22