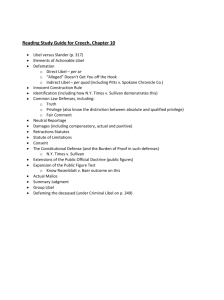

Freedom of Expression

advertisement

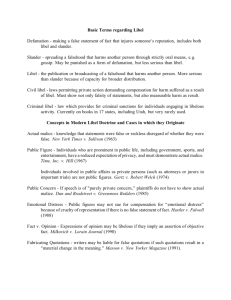

Chapter 4 Freedom of Expression Fundamental Facts About Civil Liberties No freedom is ABSOLUTE (w/o limits) Courts must balance one person’s claims of liberty against countervailing claims of liberty (or rights) of other individuals or “society” expressed in an exercise of the state’s “police powers” , i.e., the power to enact legislation for the promotion or protection of society’s health, safety, morals, or general welfare. The most fundamental liberties are those listed in the 1st Amendment No court [not withstanding individual judges] has ever interpreted the words of the 1st Amendment absolutely literally. Gitlow v N.Y., 1925 Chaplinsky v N. H., 1942 “Fighting Words” Sedition Protected Speech Obscenity & Pornography Libel/Slander Freedom of Expression Unprotected speech/expression Evolving definitions of sedition – Schenk v U.S. – “clear and present danger” Gitlow v N.Y. – “bad tendency test” Dennis v U.S. – “clear and probable danger” Mislabled – “clear though improbable danger” Brandenburg v Ohio – “incitement to imminent lawlessness” 4-4b Unprotected speech/expression Evolution of slander/libel Prior to 1964 – state laws vary, but "strict liability" [i.e., any false statement was libelous per se], and "presumed damages" [i.e., no proof required by plaintiff] were common features. Truth only defense. N.Y. Times v. Sullivan (1964) actual malice standard for public officials Curtis Pub. Co. v. Butts and Assoc. Press v. Walker (1967) – public figures must show "highly unreasonable conduct" by press [i.e., flagrant disregard for normal standards of journalistic professionalism] 4-4b Unprotected speech/expression Evolution of slander/libel 1971 Rosenbloom v. Metromedia [a fragmented Court/plurality opinion]-- even private individuals involved in events of "general or public interest" must show "actual malice;" [made libel laws nearly meaningless]. Time, Inc. v Firestone (1976) Private person must "voluntarily thrust" himself into a “public controversy,” to be treated as a public figure for libel action purposes; it is not merely someone who has been caught up in events that may be deemed "newsworthy.“ Herbert v. Lando (1979) – libel plaintiff has right to information relating to the journalistic "editorial process" in order to prove "actual malice.“ Masson v. New Yorker Magazine, Inc. (1991) – a writer who alters or fabricates statements made by the subject of an interview, then passes them off as direct statements (by the use of quotation marks around the statements) may be guilty of actual malice. 4-4b Freedom of Expression Unprotected speech/expression Sedition –speech which “incites hearers to immediate illegal action” Slander/libel – actual malice standard for public officials and public figures [knowingly saying or publishing false information] Private person must only show “fault” 4-4b Obscenity/Pornography Freedom of Expression Unprotected speech/expression Obscenity/Pornography pre-1934 U.S. courts follow English common law doctrine [known as Hicklin rule] which defined matter obscene if it "tends to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort might fall." 1934 U.S. v. One Book Entitled Ulysses -- [2d Circuit Court of Appeals] -- test for obscenity is the "dominent effect" of the material, not isolated passages, scenes, etc. 4-4b Freedom of Expression Unprotected speech/expression Obscenity/Pornography 1957 Roth v. U.S./Alberts v CA – [1st Supreme Court case on obscenity] --something is obscene if, 4-4b "to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interests." Over the next 16 years and dozens of cases a fragmented the Court could produce no majority opinion, only plurality opinions; plurality opinions have no value as precedents!] Potter Stewart’s lament Freedom of Expression Unprotected speech/expression Obscenity/Pornography Miller v CA (1973) Three-tiered test 4-4b the average person, applying contemporary community standards, finds the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interests [“community” allows for at least state by state variations] the work depicts/describes “in a patently offensive way,” sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value Unprotected speech/expression Obscenity/Pornography: Child pornography issues Protection of children from exposure/exploitation 4-4b FCC v Pacifica Foundation (1978) The context of speech matters Broadcast media never accorded same 1st Am protection as print media Court emphasized narrowness of ruling – more a “time, place, manner” than truly content-based NY v Ferber (1982) – bans use of children Reno v ACLU (1997) Bases for distinguishing this case from “precedents” “Overbreadth” doctrine Ashcroft v Free Speech Coalition (2002): can’t ban “virtual depiction” of children Unprotected speech/expression Obscenity/Pornography What constitutes government censorship? National Endowment for the Arts v Finley (1998) 4-4b O’Conner’s opinion rejects the “facial invalidity” challenge of Finley by neutering the interpretation of the challenged statute Also leaves the door open for later challenges to funding decisions by stating that “. . . the 1st Am. certainly has application in the subsidy context . . . ” Scalia’s concurring opinion “The operation was a success but the patient died.” 1st Am. irrelevant in gov’t. subsidy context – it prohibits gov’t abridgement of freedom, but does not compel evenhandedness of promotion Freedom of Expression Unprotected speech/expression Sedition –speech which “incites hearers to immediate illegal action” Slander/libel – actual malice standard [knowing saying or publishing false information] Pornography – Roth & Miller tests Fighting words – still exists in theory, but essentially a dead letter “Hate speech” 4-4b Freedom of Press Near v MN (1931) Freedom from prior restraint Limits on that right NY Times v U.S. (1971) “Strict scrutiny” standard of review 4-4b Reverse normal presumption of validity of gov’t. action Reverse “burden of proof” “Compelling interest” standard (see pp. 100-01) and features on website) Symbolic expression – “speech plus” or substitute speech Texas v Johnson (1989) The O’Brien test (U.S. v O’Brien, 1968, p. 138 & 179) Within government’s constitutional power Furthers an important or substantial gov’t. interest That interest is unrelated to suppression of free expression The incidental restriction on expression is no greater than essential to the furtherance of that interest Texas law fails test Barnes v Glen Theater (1991) Application of O’Brien test Indiana law passes test 4-4b The Right to Assemble and Petition Can be limited by municipalities’ police power to maintain public order May require permits to regulate the “time, place, and manner” of public demonstrations, assemblies, marches, etc. Such regulation can only be justified by “public safety” concerns and may NOT extend to the purpose of the march or demonstration, nor the content of signs, speeches, etc. Edwards v SC (1963) 4-6 The Right to Assemble and Petition Can be limited by municipalities’ police power to protect “non-public access” areas of public property 4-6 Adderley v FL (1966) The Right of Expressive Association Extension of right of assembly, speech, religion Boy Scouts of America v Dale (2000) What state police power is involved? What is the standard by which expressive associational rights trumps anti-discrimination statutes? 4-6