language games and secret languages

advertisement

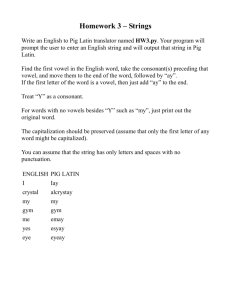

Mur-diddlyurdler! Li8 Structure of English Language games and microvariation Today’s topics What are language games? uses types What games can show us about linguistic structure and cognition What are language games? Also called ludlings, secret languages, language disguises, play languages… not technically separate languages rather, they consist of 1-2 simple phonological rules appended to the grammar of an existing language they normally manipulate phonological elements such as phonemes and syllables Uses of language games Artificial language games Natural language games For fun (“language games”) To deceive others (“language disguises”, “secret languages”) To imitate groups or languages: I just got Krusty's mother's recipe for matzoh brie! I don't do the Jewish stuff on the air! Ixnay on the Oojay! From the talk show Cooking with Krusty in the Simpsons episode Ustykray the Ownklay, The Front Some other English games Cockney rhyming slang Ubbi Dubbi/Ob/Oppen Gloppen/Pig Greek Tubo bube ubor nubot tubo bube The Name Game Pig Elvish Ovemë heten irstfë étterlé óten héten ndëen; hentë, fïén ódingca äen ordwë fóén 3 ëttërslá róen esslë, ddaén näën "en" ndíngeth; fïen odingcá äén órdwí fóén 4 ëtterslú roën órema, ddäën äen "th" ndïngeth fién hëten óvedmï etterlá sién aen ówelvú, lsëeth ddáen äën ándomrí ówëlvë. Héntï, hangëcí lläen "k" ótén "c". Ástlylú, ddáën ándómrú ccéntsáth nóen óptën fóen hëten etterslï. The Gibberish family characterized by inserting a prespecified sequence (normally VC or VCVC) before each nucleus in each word. Apparently there is variation regarding whether or not to insert the sequence before wordinitial vowels Some believe Gibberish involves [IdIg] (another calls this “Doublespeak”) Ob [ab] • Hobellobo, Thobomobas. • “My father and his cousins and siblings are the most likely to use it. Last summer a youngster wondered how to say 'Neosporin' in Ob. My father left the room and came back several minutes later, announcing triumphantly, "nobeobospoborobin". I think everyone just refers to it with that name, now.” Ubbi Dubbi [] or [] • perhaps introduced on the PBS show ZOOM, or alternately, as a joke in a sketch by Bill Cosby (the Dentist sketch) • "To be or not to be" → "Tubo bube ubor nubot tubo bube“ • Used by Mushmouth on Fat Albert; cf. Partridge Family skit on SNL Double Dutch [g] (spelled <ag> or <eg> (the latter also called Egg Latin)) • Heggow eggare yeggou deggoegging? • Or “replace every C with a syllable starting and ending with that consonant suso wuworordodzuz cucouldud gogetut popruretutty lolongung” Op, Oppish, Oppen Gloppen [ap] Slov [av] [name unknown] <ubbagg> [combines Ubbi Dubbi and Double Dutch] • Yubbaggou dubbaggon't wubbaggant tubbaggo knubbaggow. Other English examples Bicycle ([s] after each non-final consonant [or is it C-cluster?…]) Pig Greek (<ob> after each consonant) Dong Spelling out words, using: • V: unaltered • C → C + <ong> • Let's go → Long ee tong song gong oh Chinese Pig Latin ([an] after C, [gan] after V) various Simpsons games Ned Flanders: -(d)iddly-, skerdəlider = scare, okəlidokəli = okeedokee, murdidliurdler = murder, pred-iddly-ictable Zambuda “English pronounced wrong in every possible way. Long vowels became short, c pronounced s when usually pronounced k, silent letters pronounced, and so on. So a sentence like "knock before entering" would become "kE-nOsk beh-faw-ree een-tee-rynj." (E=schwa, O=long o) Being high school students, we mostly used it for words like "mOt-heer-foo-skeer," but some guys got to the point where they could converse fluently in it” Identity avoidance Name Game “But if the first two letters are ever the same, I drop them both and say the name. Like Bob, Bob drop the B like ob Or Fred, Fred drop the F go red Mary, Mary drop the M so ary That's the only rule that is contrary.” Fee fie mo Ichael (not *Michael) w-, y-, and h-dialects of Pig Latin W: way vs. a Y: you vs. ooh/eww H: who vs. ooh/eww Phonemes vs. graphemes Talking backwards (Cowan, Leavitt, Massaro & Kent 1982) 31-year-old philosophy professor • negotiating for peace [negošietiŋ fOr pis] [gniteIšogen rOf sip] half of backward talkers reverse a phonological representation of each word; the other half reverse orthographic representation. Woman talking backward (Cowan & Leavitt 1992) Example: garage [graž] reversed as [žarg] Evidence that she reverses phonemes (rather than letters): • 1. no silent letters pronounced in reverse forms • 2. homographs were always pronounced differently (two <g>'s in garage) Not functioning as "reversed tape recorders": • Compound units (diphthongs and affricates) were consistently preserved as units rather than being reversed. • choice [tšojs] was reversed as [sojtš] (rather than *[sjošt]) • This reflects phonological constraints on the woman's acoustic analytic capabilities. Underdetermination microvariation in Pig Latin/ Backslang Definition of the Underdetermination Thesis (e.g. Quine 1975) “"Given any amount of data, there are always (infinitely) many hypotheses which fit equally well with the data.” Underdetermination of sampled waveforms Digital sampling of analog waveforms yields a set of discrete points, not a continuous wave The shape of the wave is inferred from these points by an equation that yields a curve of most likely fit As the Underdetermination Thesis points out, there is actually an infinite number of waveforms compatible with these points Elaboration:… sampled points (time/amplitude pairs) inferred curve of best fit excerpt from waveform of me saying [aaaa] at 91 Hz Two analyses compatible with the data 14 12 10 Input Data 8 f(x) 2x^2 - 6x + 6 6 -8x^6 + 72.8x^5 - 250*x^4 + 401*x^3 - 297*x^2 + 79.2*x + 6 4 2 x 3 2. 7 2. 4 2. 1 1. 8 1. 5 1. 2 0. 9 0. 6 0. 3 0 0 Pig Latin Trigger typically ig-pay atin-Lay How would you formalize the rule(s)? What predictions does each rule hypothesis make for other types of form? ig-pay atin-lay = imple-say? Traditional View of Pig Latin: “A jargon systematically formed by the transposition of the initial consonant to the end of the word and the suffixation of an additional syllable” (The American Heritage Dictionary (1992:1372)) What if the word doesn’t have an initial C? What if the word has more than one initial C? Second try at a formulation: SPE “Pig Latin…is defined by…a rule which moves the initial consonant sequence in the word, if any, to the end, and which then adds the sequence [ey] to its right” (Chomsky & Halle 1968:342) Predictions: vowel-initial words (e.g. oven) should yield the output oven-ay, complex onsets (e.g. tree) should yield ee-tray Complex Onsets: dialect variation with truck 90 77.7 80 70 60 50 40 30 19.4 20 10 2.1 0 uck-tr-ay ruck-t-ay uck-tray (transpose entire onset) ruck-tay (transpose initial C) ruck-tray (transpose entire onset, retain 2nd C) No productions of *tuck-ray, *tuck-tray! ruck-tr-ay (n = 449) (n = 112) (n = 12) VCV-initial words: dialect variation with oven 40 36 35 30 25 20 15.6 14 15 9.3 10 8.1 7.6 6.2 1.9 5 1 0.7 0.2 0.2 0.2 oven-ov- w-oven- ay w-ay 0 oven-ay ven-o-ay oven-way oven-hay oven-yay en-ov-ay NULL ven-ov-ay oven-v-ay h-oven-h- y-ovenay oven-ay (add -ay) ven-o-ay (initial transposition) oven-way (add w) oven-hay (add h) oven-yay(add y) en-ov-ay (initial transposition) no output (n = 208) ven-ov-ay oven-v-ay (n = 90) (n = 82) (n = 54) h-oven-h-ay y-oven-y-ay ven-ay (n = 47) (n = 44) oven-n-ay (n = 36) w-oven-w-ay oven-ov-ay yay (copy max + del.) (1st consonant copying) (add h, overapplication!) (add y, overapplication!) (delete first V) (add n) (add w, overapplication!) (copy max ) (n = 11) (n = 6) (n = 4) (n = 2) (n = 2) (n = 2) (n = 1) (n = 1) Appendix vs. complex onset Many phonological processes treat clusters of rising sonority (e.g -tr-) differently than clusters of falling sonority (-rt-). Does this surface in language games? 40/499 (8%) treat tr- and sc- differently in survey NB no evidence for this difference in trigger data Cf. Pierrehumbert and Nair 1995: Made-up game that inserts -ətStimuli limited to CVAfter conditioning, test CCV- words Finding: sO- and OR- clusters treated differently Conclusions Psychological reality/universality of identity avoidance Psychological reality of phonemes Games typically manipulate phonemes, not graphemes Inventory of computations Disparity in fast vs. careful performance