Lyndon B. Johnson's Bio

advertisement

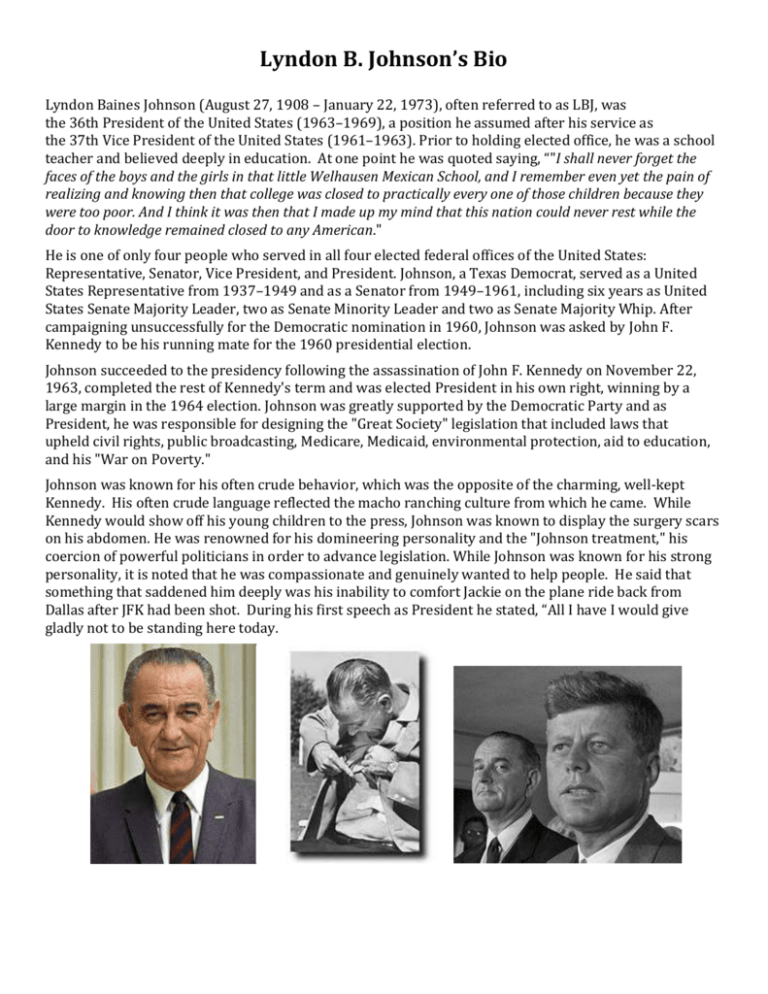

Lyndon B. Johnson’s Bio Lyndon Baines Johnson (August 27, 1908 – January 22, 1973), often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States (1963–1969), a position he assumed after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States (1961–1963). Prior to holding elected office, he was a school teacher and believed deeply in education. At one point he was quoted saying, “"I shall never forget the faces of the boys and the girls in that little Welhausen Mexican School, and I remember even yet the pain of realizing and knowing then that college was closed to practically every one of those children because they were too poor. And I think it was then that I made up my mind that this nation could never rest while the door to knowledge remained closed to any American." He is one of only four people who served in all four elected federal offices of the United States: Representative, Senator, Vice President, and President. Johnson, a Texas Democrat, served as a United States Representative from 1937–1949 and as a Senator from 1949–1961, including six years as United States Senate Majority Leader, two as Senate Minority Leader and two as Senate Majority Whip. After campaigning unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination in 1960, Johnson was asked by John F. Kennedy to be his running mate for the 1960 presidential election. Johnson succeeded to the presidency following the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, completed the rest of Kennedy's term and was elected President in his own right, winning by a large margin in the 1964 election. Johnson was greatly supported by the Democratic Party and as President, he was responsible for designing the "Great Society" legislation that included laws that upheld civil rights, public broadcasting, Medicare, Medicaid, environmental protection, aid to education, and his "War on Poverty." Johnson was known for his often crude behavior, which was the opposite of the charming, well-kept Kennedy. His often crude language reflected the macho ranching culture from which he came. While Kennedy would show off his young children to the press, Johnson was known to display the surgery scars on his abdomen. He was renowned for his domineering personality and the "Johnson treatment," his coercion of powerful politicians in order to advance legislation. While Johnson was known for his strong personality, it is noted that he was compassionate and genuinely wanted to help people. He said that something that saddened him deeply was his inability to comfort Jackie on the plane ride back from Dallas after JFK had been shot. During his first speech as President he stated, “All I have I would give gladly not to be standing here today. The War On Poverty The War on Poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national poverty rate of around nineteen percent. The speech led the United States Congress to pass the Economic Opportunity Act, which established the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) to administer the local application of federal funds targeted against poverty. As a part of the Great Society, Johnson believed in expanding the government's role in education and health care as poverty reduction strategies. These policies can also be seen as a continuation of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, which ran from 1933 to 1935, and the Four Freedoms of 1941. The Office of Economic Opportunity was the agency responsible for administering most of the War on Poverty programs created during Johnson's Administration, including VISTA, Job Corps, Head Start, Legal Services and the Community Action Program. The OEO was established in 1964 and quickly became a target of both left-wing and right-wing critics of the War on Poverty. Directors of the OEO included Sargent Shriver, Bertrand Harding, and Donald Rumsfeld. The OEO launched Project Head Start as an eight-week summer program in 1965. The project was designed to help end poverty by providing preschool children from low-income families with a program that would meet emotional, social, health, nutritional, and psychological needs. Head Start was then transferred to the Office of Child Development in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (later the Department of Health and Human Services) by the Nixon Administration in 1969. President Johnson also announced a second project to follow children from the Head Start program. This was implemented in 1967 with Project Follow Through, the largest educational experiment ever conducted. The policy trains disadvantaged and at-risk youth and has provided more than 2 million disadvantaged young people with the integrated academic, vocational, and social skills training they need to gain independence and get quality, long-term jobs or further their education. Job Corps continues to help 70,000 youths annually at 122 Job Corps centers throughout the country. Besides vocational training, many Job Corps also offer GED programs as well as high school diplomas and programs to get students into college. The Great Society The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States promoted by President Lyndon B. Johnson and fellow Democrats in Congress in the 1960s. Two main goals of the Great Society social reforms were the elimination of poverty and racial injustice. New major spending programs that addressed education, medical care, urban problems, and transportation were launched during this period. The Great Society in scope and sweep resembled the New Deal domestic agenda of Franklin D. Roosevelt, but differed sharply in types of programs enacted. Some Great Society proposals were stalled initiatives from John F. Kennedy's New Frontier. Johnson's success depended on his skills of persuasion, coupled with the Democratic landslide in the 1964 election that brought in many new liberals to Congress, making the House of Representatives in 1965 the most liberal House since 1938. Anti-war Democrats complained that spending on the Vietnam War choked off the Great Society. While some of the programs have been eliminated or had their funding reduced, many of them, including Medicare, Medicaid, the Older Americans Act and federal education funding, continue to the present. The Great Society's programs expanded under the administrations of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Education The most important educational component of the Great Society was the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, designed by Commissioner of Education Francis Keppel. It was signed into law on April 11, 1965, less than three months after it was introduced. It ended a long-standing political taboo by providing significant federal aid to public education, initially allotting more than $1 billion to help schools purchase materials and start special education programs to schools with a high concentration of low-income children. The Act established Head Start, which had originally been started by the Office of Economic Opportunity as an eight-week summer program, as a permanent program. The Higher Education Facilities Act of 1963, which was signed into law by Johnson a month after becoming president, authorized several times more college aid within a five-year period than had been appropriated under the Land Grant College in a century, and provided better college libraries, ten to twenty new graduate centers, several new technical institutes, classrooms for several hundred thousand students, and twenty-five to thirty new community colleges a year. This major piece of legislation was followed by the Higher Education Act of 1965, which increased federal money given to universities, created scholarships and low-interest loans for students, and established a national Teacher Corps to provide teachers to poverty-stricken areas of the United States. The Act also began a transition from federally funded institutional assistance to individual student aid. The Bilingual Education Act of 1968 offered federal aid to local school districts in assisting them to address the needs of children with limited English-speaking ability until it expired in 2002. The Social Security Act of 1965 authorized Medicare and provided federal funding for many of the medical costs of older Americans. The legislation overcame the bitter resistance, particularly from the American Medical Association, to the idea of publicly funded health care or "socialized medicine" by making its benefits available to everyone over sixty-five, regardless of need, and by linking payments to the existing private insurance system. In 1966 welfare recipients of all ages received medical care through the Medicaid program. Medicaid was created on July 30, 1965 under Title XIX of the Social Security Act of 1965. Each state administers its own Medicaid program while the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) monitors the state-run programs and establishes requirements for service delivery, quality, funding, and eligibility standards. Consumer protection In 1964, Johnson named Assistant Secretary of Labor Esther Peterson to be the first presidential assistant for consumer affairs. The Cigarette Labeling Act of 1965 required packages to carry warning labels. The Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 set standards through creation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The Fair Packaging and Labeling Act requires products identify manufacturer, address, clearly mark quantity and servings. The statute also authorizes permits HEW and FTC to establish and define voluntary standard sizes. The original would have mandated uniform standards of size and weight for comparison shopping, but the final law only outlawed exaggerated size claims. Child Safety Act of 1966 prohibited any chemical so dangerous that no warning can make it safe. The Flammable Fabrics Act of 1967 set standards for children's sleepwear, but not baby blankets. The Wholesome Meat Act of 1967 required inspection of meat which must meet federal standards. The Truth-in-Lending Act of 1968 required lenders and credit providers to disclose the full cost of finance charges in both dollars and annual percentage rates, on installment loan and sales. The Wholesome Poultry Products Act of 1968 required inspection of poultry which must meet federal standards. The Land Sales Disclosure Act of 1968 provided safeguards against fraudulent practices in the sale of land. The Radiation Safety Act of 1968 provided standards and recalls for defective electronic products. Johnson’s Great Society also created legislation to help transportation, and created the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities . It also created the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 which chartered the Corporation for Public Broadcasting as a private, nonprofit corporation (PBS). Johnson also created legislation to protect the environment. Civil Rights Legislation The Civil Rights Act of 1957, enacted September 9, 1957, primarily a voting rights bill, was the first civil rights legislation enacted by Congress in the United States since Reconstruction following the American Civil War. Following the historic US Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which eventually led to the integration of public schools, Southern whites in Virginia began a "Massive Resistance". Violence against blacks rose there and in other states, as in Little Rock, Arkansas, where that year President Dwight D. Eisenhower had ordered in federal troops to protect nine children integrating a public school, the first time the federal government had sent troops to the South since Reconstruction. There had been continued physical assaults against suspected activists and bombings of schools and churches in the South. The administration of Eisenhower proposed legislation to protect the right to vote by African Americans. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, an ardent segregationist, sustained the longest oneperson filibuster in history in an attempt to keep the bill from becoming law. His one-man filibuster lasted 24 hours and 18 minutes; he began with readings of every state's election laws in alphabetical order. Thurmond later read from the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and George Washington's Farewell Address. His speech set the record for a Senate filibuster. The bill passed the House with a vote of 270 to 97 and the Senate 60 to 15. President Eisenhower signed it on September 9, 1957 The Civil Rights Act of 1964, enacted July 2, 1964, was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States[1] that outlawed major forms of discrimination against African Americans and women, including racial segregation. It ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace and by facilities that served the general public ("public accommodations"). Powers given to enforce the act were initially weak, but were supplemented during later years. Congress asserted its authority to legislate under several different parts of the United States Constitution, principally its power to regulate interstate commerce under Article One (section 8), its duty to guarantee all citizens equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment and its duty to protect voting rights under the Fifteenth Amendment. The Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, who would later sign the landmark Voting Rights Act into law The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of national legislation in the United States that outlawed discriminatory voting practices that had been responsible for the widespread disenfranchisement of African Americans in the U.S. Echoing the language of the 15th Amendment, the Act prohibits states from imposing any "voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure ... to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color." Specifically, Congress intended the Act to outlaw the practice of requiring otherwise qualified voters to pass literacy tests in order to register to vote, a principal means by which Southern states had prevented African-Americans from exercising the franchise. The Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Democrat, who had earlier signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. The Act established extensive federal oversight of elections administration, providing that states with a history of discriminatory voting practices (so-called "covered jurisdictions") could not implement any change affecting voting without first obtaining the approval of the Department of Justice, a process known as preclearance. These enforcement provisions applied to states and political subdivisions (mostly in the South) that had used a "device" to limit voting and in which less than 50 percent of the population was registered to vote in 1964. The Act has been renewed and amended by Congress four times, the most recent being a 25-year extension signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2006. The Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, (was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States that provided for equal housing opportunities regardless of race, creed, or national origin. The Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had previously signed the landmark Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act into law. Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 is commonly known as the Fair Housing Act and was meant as a follow-up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. While the Civil Rights Act of 1866[1] prohibited discrimination in housing, there were no federal enforcement provisions. The 1968 act expanded on previous acts and prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, and since 1974, gender; since 1988, the act protects people with disabilities and families with children. Victims of discrimination may use both the 1968 act and the 1866 act via section 1983 to seek redress. The 1968 act provides for federal solutions while the 1866 act provides for private solutions (i.e., civil suits). A rider attached to the bill makes it a felony to "travel in interstate commerce... with the intent to incite, promote, encourage, participate in and carry on a riot..." This provision has been criticized for "equating organized political protest with organized violence." Miranda vs. Arizona Miranda v. Arizona, (1966), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court which passed 54. The Court held that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant was informed of the right to consult with an attorney before and during questioning and of the right against self-incrimination prior to questioning by police, and that the defendant not only understood these rights, but voluntarily waived them. This had a significant impact on law enforcement in the United States, by making what became known as the Miranda rights part of routine police procedure to ensure that suspects were informed of their rights. The Supreme Court decided Miranda with three other consolidated cases: Westover v. United States, Vignera v. New York, and California v. Stewart. The Miranda warning (often abbreviated to "Miranda," or "Mirandizing" a suspect) is the name of the formal warning that is required to be given by police in the United States to criminal suspects in police custody (or in a custodial situation) before they are interrogated, in accordance with the Miranda ruling. Its purpose is to ensure the accused is aware of, and reminded of, these rights under the U.S. Constitution, and that they know they can invoke them at any time during the interview. Ernesto Arturo Miranda was arrested based on circumstantial evidence linking him to the kidnapping and rape of an 18-year-old woman 10 days earlier. After two hours of interrogation by police officers, Miranda signed a confession to the rape charge on forms that included the typed statement "I do hereby swear that I make this statement voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion, or promises of immunity, and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make may be used against me." However, at no time was Miranda told of his right to counsel, and he was not advised of his right to remain silent or that his statements would be used against him during the interrogation before being presented with the form on which he was asked to write out the confession he had already given orally. At trial, when prosecutors offered Miranda's written confession as evidence, his court-appointed lawyer, Alvin Moore, objected that because of these facts, the confession was not truly voluntary and should be excluded. Moore's objection was overruled and based on this confession and other evidence, Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20 to 30 years imprisonment on each charge, with sentences to run concurrently. Moore filed Miranda's appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court claiming that Miranda's confession was not fully voluntary and should not have been admitted into the court proceedings. The Arizona Supreme Court affirmed the trial court's decision to admit the confession in State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d 721 (Ariz. 1965). In affirming, the Arizona Supreme Court emphasized heavily the fact that Miranda did not specifically request an attorney. Chief Justice Earl Warren, a former prosecutor, delivered the opinion of the Court, ruling that due to the coercive nature of the custodial interrogation by police (Warren cited several police training manuals which had not been provided in the arguments), no confession could be admissible under the Fifth Amendment self-incrimination clause and Sixth Amendment right to an attorney unless a suspect had been made aware of his/her rights and the suspect had then waived them: The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him. Thus, Miranda's conviction was overturned. The Court also made clear what had to happen if the suspect chose to exercise his or her rights: If the individual indicates in any manner, at any time prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease ... If the individual states that he wants an attorney, the interrogation must cease until an attorney is present. At that time, the individual must have an opportunity to confer with the attorney and to have him present during any subsequent questioning. Although the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had urged the Supreme Court to require the mandatory presence of a "station-house" lawyer at all police interrogations, Warren refused to go that far, or to even include a suggestion that immediately demanding a lawyer would be in the suspect's best interest. Warren pointed to the existing practice of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the rules of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, both of which required notifying a suspect of his right to remain silent; the FBI warning included notice of the right to counsel. However, the dissenting justices thought that the suggested warnings would ultimately lead to such a drastic effect—they apparently believed that once warned, suspects would always demand attorneys and deny the police the ability to seek confessions and accordingly accused the majority of overreacting to the problem of coercive interrogations.